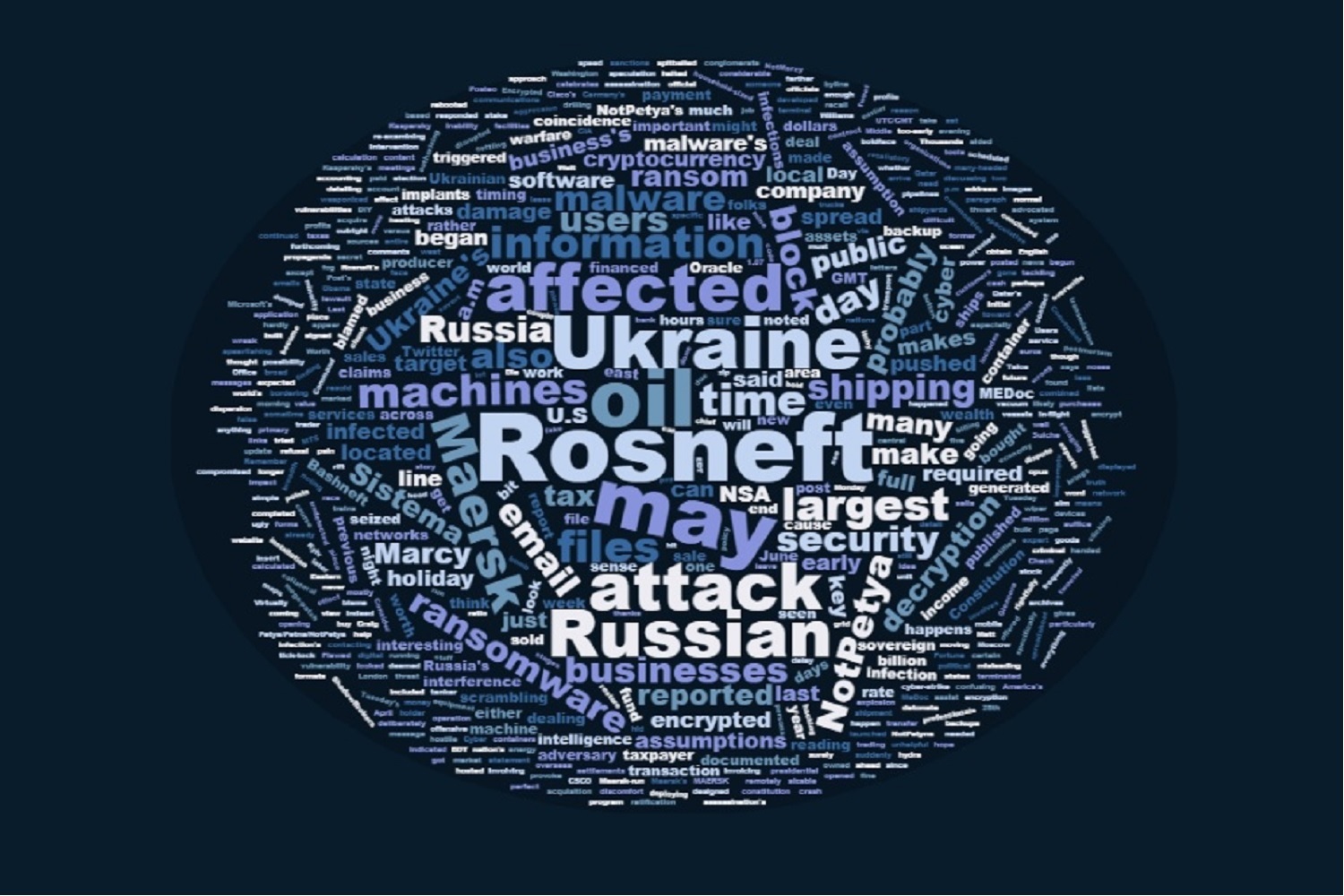

Nyetya: Sanctions and Taxes

In my first post on the Nyetya/NotPetya attack launched in Ukraine last week, I suggested the attack looked a lot like a digital sanctions regime and pointed out that the malware had been compiled not long after the US Senate tried to pass new sanctions.

On June 14, the Senate passed some harsh new sanctions on Russia, ostensibly just for Russia’s Ukrainian and Syrian related actions, not for its tampering in last year’s US election. The House mucked up that bill, but the Senate will continue to try to impose new sanctions. Trump might well veto the sanctions, but that will cause him a great deal of political trouble amid the Russian investigation.

The Petya/NotPetya malware was compiled on June 18.

Update: I should add that Treasury added a bunch of people to its Ukraine-related sanctions list on June 20.

In her first post on it, Rayne focused on how the loss of MEDoc’s tax software might effect payments in Ukraine (though she remained open about other attackers besides Russia).

But the US wasn’t the only country that has moved towards imposing new sanctions on Russia. Ukraine did so too, back on May 15. Petro Poroshenko targeted a number of Russian tech brands — most spectacularly, VK, mail.ru, and Yandex, which are among the most popular sites in Ukraine. The Ukrainian president also banned Kaspersky, as American politicians are moving closer to doing. Most interestingly, Poroshenko banned 1C, maybe the equivalent of Microsoft’s Office suite.

A decree by Poroshenko posted late on Monday expanded sanctions adopted over Russia’s annexation of Crimea and backing of separatists in eastern Ukraine to include 468 companies and 1,228 people. Among them were the Russian social networks VK and Odnoklassniki, the email service Mail.ru and the search engine company Yandex, all four of which are in the top 10 most popular sites in Ukraine, according to the web traffic data company Alexa. The decree requires internet providers to block access to the sites for three years.

Poroshenko’s decree also blocked the site of the Russian cybersecurity giant Kaspersky Labs and will ban several major Russian television channels and banks, as well as the popular business software developer 1C.

In a post on his official page on VK, Poroshenko said he had tried to use Russian social networks to fight Russia’s “hybrid war” and propaganda.

1C is a competitor to MEDoc, the patient zero of the attack. (h/t Jeff Vader)

After Poroshenko imposed sanctions, Putin’s spox warned Ukraine had forgotten the principle of reciprocity.

Vladimir Putin’s spokesman told journalists that he wasn’t prepared to say but that Russia had not “forgotten about the principle of reciprocity”.

Now consider these other details.

It turns out that MEDoc had already sent out several malicious updates which backdoored the software and collected the unique business identifier of the victims, as well as credentials.

During our research, we identified a very stealthy and cunning backdoor that was injected by attackers into one of M.E.Doc’s legitimate modules. It seems very unlikely that attackers could do this without access to M.E.Doc’s source code.

The backdoored module has the filename ZvitPublishedObjects.dll. This was written using the .NET Framework. It is a 5MB file and contains a lot of legitimate code that can be called by other components, including the main M.E.Doc executable ezvit.exe.

We examined all M.E.Doc updates that were released during 2017, and found that there are at least three updates that contained the backdoored module:

- 01.175-10.01.176, released on 14th of April 2017

- 01.180-10.01.181, released on 15th of May 2017

- 01.188-10.01.189, released on 22nd of June 2017

The incident with Win32/Filecoder.AESNI.C happened three days after the 10.01.180-10.01.181 update and the DiskCoder.C outbreak happened five days after the 10.01.188-10.01.189 update. Interestingly, four updates from April 24th 2017, through to May 10th 2017, and seven software updates from May 17th 2017, through to June 21st 2017, didn’t contain the backdoored module.

Since the May 15th update did contain the backdoored module and the May 17th update didn’t, here is a hypothesis that could explain low infection Win32/Filecoder.AESNI.C ratio: the release of the May 17th update was an unexpected event for the attackers. They pushed the ransomware on May 18th, but the majority of M.E.Doc users no longer had the backdoored module as they had updated already.

[snip]

Each organization that does business in Ukraine has a unique legal entity identifier called the EDRPOU number (Код ЄДРПОУ). This is extremely important for the attackers: having the EDRPOU number, they could identify the exact organization that is now using the backdoored M.E.Doc. Once such an organization is identified, attackers could then use various tactics against the computer network of the organization, depending on the attackers’ goal(s).

[snip]

Along with the EDRPOU numbers, the backdoor collects proxy and email settings, including usernames and passwords, from the M.E.Doc application.

Note, that May 15 attack was actually earlier in the day, before Poroshenko announced the sanctions against Russia.

Talos used logs it obtained from MEDoc to confirm that it backdoored the victims, collecting data from targeted machines.

But then it makes what I consider a logical jump (albeit an interesting one): invoking something similar that happened with Blackenergy, it argues that the hacker that had backdoored MEDoc has lost the intelligence functionality of the MEDoc back door, so it must have a replacement at the ready. As a result, Talos basically suggests that businesses should treat anything touching Ukraine as if it has or soon will have digital cooties.

In short, the actor has given up the ability to deliver arbitrary code to the 80% of UA businesses that use M.E.Doc as their accounting software, along with any multinational corporations that leveraged the software. This is a significant loss in operational capability, and the Threat Intelligence and Interdiction team assesses with moderate confidence that it is unlikely that they would have expended this capability without confidence that they now have or can easily obtain similar capability in target networks of highest priority to the threat actor.

Based on this, Talos is advising that any organization with ties to Ukraine treat software like M.E.Doc and systems in Ukraine with extra caution since they have been shown to be targeted by advanced threat actors. This includes providing them a separate network architecture, increased monitoring and hunting activities in those at-risk systems and networks and allowing only the level of access absolutely necessary to conduct business. Patching and upgrades should be prioritized on these systems and customers should move to transition these systems to Windows 10, following the guidance from Microsoft on securing those systems. Additional guidance for network security baselining is available from Cisco as well. Network IPS should be deployed on connections between international organizations and their Ukrainian branches and endpoint protection should be installed immediately on all Ukrainian systems.

That may be right. But I’m not sure this analysis considers Rayne’s point: that by basically taking out crucial tax software used by 80% of the Ukrainian market (indeed, Ukrainian authorities raided the company in a showy SWAT raid today), you will presumably have some effect on the collection of taxes in Ukraine, something AP’s reporter reporting from Ukraine, Raphael Satter, says he has seen anecdotal evidence of already.

So, sure, the MEDoc attacker lost the back door into 80% of the companies doing business in Ukraine. But the attacker may have hurt Ukraine’s ability to collect taxes, even while destroying the Ukrainian competitor to one of the companies targeted in May, imposing tremendous costs on doing business in Ukraine, and leading security advisors to recommend treating Ukraine like it has cooties going forward.

As with my first post on this, I’m still really just spit balling.

But one thing we know about Russia: it wants to find a way to end the sanctions regimes against it, and helping Donald Trump get elected thus far hasn’t done the trick.

Update: Malware Tech, the guy who sinkholed WannaCry, points to his data showing declining WannaCry infections in Ukraine and Russia, which he says shows the effect of the Nyetya infections replacing WannaCry ones. That suggests the impact in Russia is real, contrary to some public comments.

Update: Bleeping Computers describes victims installing old versions of MEDoc because it is so central to their business operations.

With the M.E.Doc servers down, Bleeping Computer was told that most Ukrainian companies are now sharing older versions of the M.E.Doc software via Google Drive links. The software provided by Intellect Service is so crucial to Ukrainian companies that even after the NotPetya outbreak, many businesses cannot manage their finances without it, despite the looming danger of another incident.

Because of the way the software is currently shared between some usrs, Ukrainian companies are now exposing themselves to even more dangerous threats, such as installing boobytrapped M.E.Doc versions from unofficial sources like Dropbox or Google Drive.