Freedom And Equality: Relational Equality Against Social Hierarchies

Introduction and Posts in This Series with additional resources

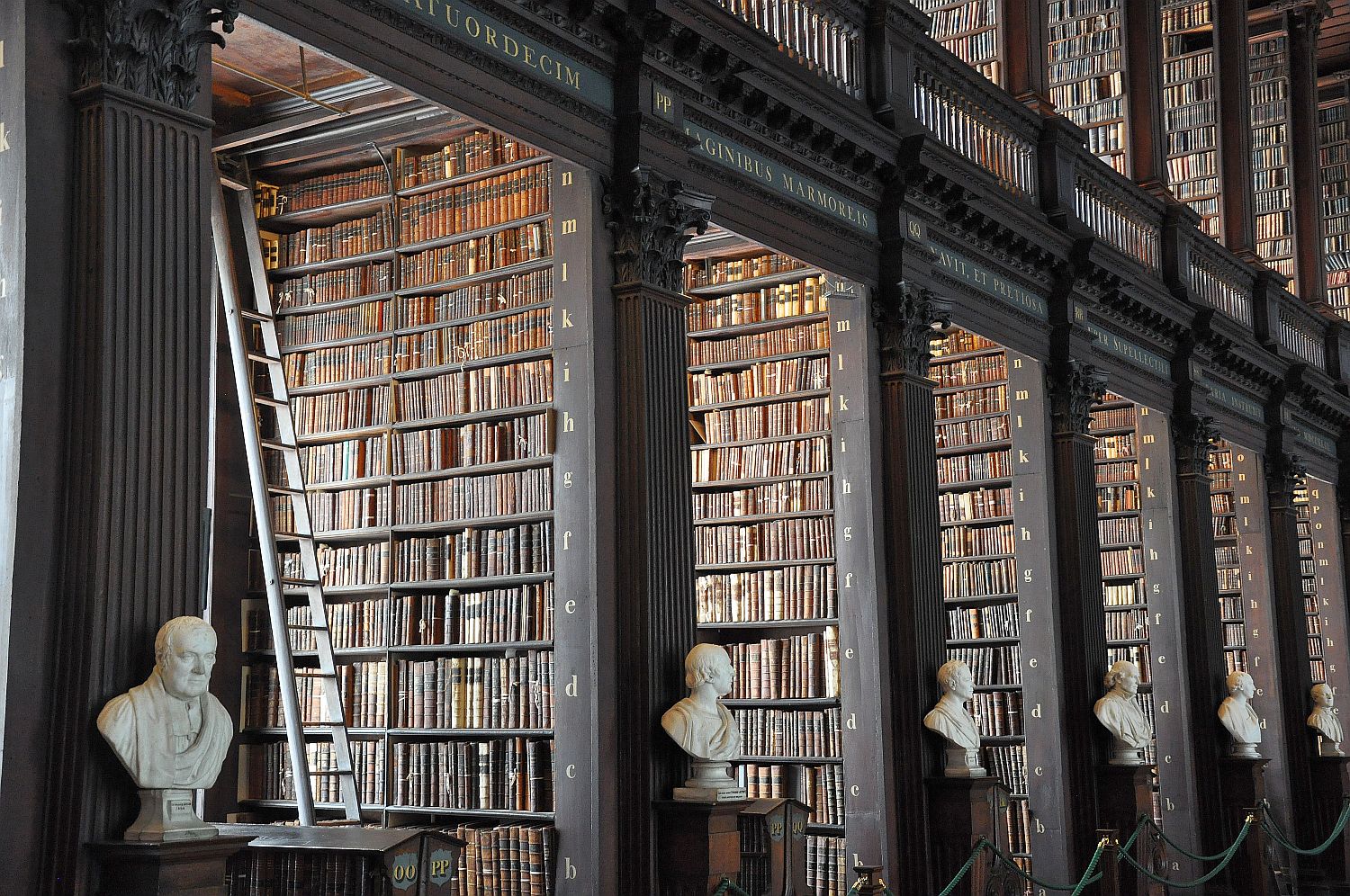

The first two posts in this series discuss the idea of freedom from domination as used by Elizabeth Anderson in a chapter she wrote for The Oxford Handbook of Freedom and Equality, which you can find online through your public library, I hope. With this post, I begin looking at the concept of equality as she uses it. In subsequent posts I will examine her thinking on managing the relation between freedom and equality.

Anderson says that the type of equality relevant for political purposes is relational equality, as opposed to material equality. Material equality is the idea that we should all have the same quantity of resources, and no one actually advocates this, or anything like it, despite right-wing shrieks about socialism.

Relational equality is defined against social hierarchy. To get a better understanding of this idea, I turn to another chapter by Anderson, Equality, published in The Oxford Handbook of Political Philosophy. Anderson argues for an understanding of equality as an “ideal of social relations”. In contemporary thought, including not least contemporary philosophical thought, equality is considered as a principle governing distribution of economic goods. The discussion is often based on the ideas of John Rawls in A Theory of Justice. Rawls has been interpreted as requiring some level of equality of distribution, leading to tedious (my word) discussions of what, how much, and who is deserving of such redistribution.

Anderson argues that relational equality is a much more accurate description of what egalitarians actually work for, what they actually are doing.

A Side Note On Method

Anderson considers herself a pragmatist in the tradition of John Dewey. Another of Dewey’s disciples, Richard Rorty, wrote

Dewey’s philosophy is a systematic attempt to temporalize everything, to leave nothing fixed. This means abandoning the attempt to find a theoretical frame of reference within which to evaluate proposals for the human future.*

This means precisely that human beings created all the moral and ethical principles that we use to measure good and evil, right and wrong, moral and immoral, decent and indecent, acceptable and unacceptable, edible or inedible, taboo and prized acts, included and excluded groups, and every other pairing of measures. Every social structure is created by humans. There is no external, no objective set of principles for any of these purposes. There are only human beings struggling with themselves and others to structure their mutual existence. It means that human beings create their own future.

That’s not to say that we don’t have standards for making decisions. We most certainly do. But we have to recognize that others are perfectly capable of forming other coherent standards that disagree with ours, and that living with others necessitates accommodation to their plans. It doesn’t mean that we don’t have absolutes in our lives, but it may mean that we do not attempt to impose those on others.

Anderson works from the principle that social choices are matters of argument among members of society. She says that choosing between relational equality and social hierarchies is a matter of values. She sets out the values she thinks are important and argues about which is superior in terms of those values. This kind of argument appears regularly in her work.

Social Hierarchy

By “social hierarchy”, I refer to durable group inequalities that are systematically sustained by laws, norms, or habits.

Anderson adds that social hierarchies are durable, they persist through generations. They are group-based: one group is superior, the other inferior. They are typically based on broad categories, race, gender, sexuality, citizenship and so on. She identifies three kinds of social hierarchy, hierarchies of command, hierarchies of esteem, and hierarchies of standing.

In hierarchies of command, the inferior class is subject to arbitrary and unaccountable control by the superior class. The inferior class must obey the orders of the superior class without questioning. Inferiors cannot exercise their liberty without the assent of the superior class. This is the opposite of the non-domination I discussed in the two previous posts in this series. This hierarchy is undone when the inferior class is able to govern itself directly or democratically.

In hierarchies of esteem the superior class stigmatizes the inferior class. The inferior class is marked for disdain, ridicule, humiliation and even violent persecution.

In hierarchies of standing, the interests and voices of the superior class are given great weight in social decision-making, legislation, and enforcement of laws and rules. The interests of the inferior class are given little or no weight in such matters.

Values

Anderson follows John Dewey’s scheme of values in the following passage.

The realm of values is divided into three great domains: the good, the right, and the virtuous. Each is defined in relation to the perspective from which people make judgments about each type. Judgments of goodness are made from a first-person perspective—that is, from the perspective of one enjoying, remembering, or anticipating the enjoyment of some object, individually or in concert with others (“us”). The experience of goodness—the sign or evidence of goodness—is one’s felt attraction to an appealing object. Judgments of moral rightness are made from a second-person perspective, in which one person asserts the authority (in his or her own person or on behalf of another) to make claims on another—to demand that the other respect the rights or pay due regard to the interests of the claimant and to hold the other accountable for doing so. Judgments of moral wrongness, therefore, are essentially expressible as complaints by or on behalf of a victim that are addressed to agents who are held responsible for wrongdoing. The experience of encountering a valid claim of rightness is that of feeling required to do something, of being commanded by a legitimate authority. Judgments of virtue are made from the third-person perspective of an observer and judge of people’s conduct and underlying dispositions. The experience of virtue is one’s felt approval or admiration of people’s character or powers as expressed in their conduct. Citations omitted.

This is a lot to process. Perhaps the first step is to try to apply these ideas to your personal thinking about social issues. Consider the family separation policy applied to asylum seekers by Trump (Miller). When I think of it in terms of the good, the right and the virtuous, I immediately see that it makes me want to act, to demand justice. It makes me despise the people who instigated this policy and the people who carry it out. Therefore I perceive it as neither right (just) nor virtuous. I also see that it is evil, the opposite of good; it doesn’t make me happy, it makes me angry and hostile.

On the other hand, to judge from Twitter and what I see of Fox news on comedy shows, there are plenty of people who don’t see it that way. Is it possible to have a discussion of values with such people? Is there an argument that the policy is good or right or virtuous? Am I prepared to admit such arguments might be worth considering?

Relational Equality Against Social Hierarchies

This is the central argument of Anderson’s chapter. Anderson claims that egalitarians argue that social hierarchies are bad on all three counts. In general, social hierarchies are not right ( meaning they are unjust) towards the people placed in the inferior class and thus to society as a whole. They are morally wrong (virtue) towards both superior and inferior classes because it devalues the human worth and potential of the inferior class and inflates the worth of the superior class. And they are vicious (not good) because they treat the ideologies supporting this class distinction as good when we can see that those ideologies are corrupt.

In the case of esteem hierarchies, egalitarians argue that all human beings are entitled to a basic level of esteem and equal access to higher levels of esteem. As to hierarchies of standing, egalitarians argue that all humans should be treated equally before the law, and should have a basal level of standing in other settings.

With respect to command hierarchies, egalitarians argue that the primary justification is the idea that some humans are fit to rule and other are fit only to follow. Egalitarians say that all humans possess a basic level of self-government sufficient to enable them to participate in decisions about their lives and work, and “…entitle them to reject systems in which others wield unaccountable power over them.”

These ideas may not be comfortable. The arguments may seem unanchored, because there isn’t a Ten Commandments or any other seemingly objective standard. I’ll have other comments in the next post.

====

*Rorty, Achieving Our Country, p. 20. This is a great book, an antidote to the despair that alternates with cynicism that infects the American left. I may do a series on it, but it’s easy to read, barely theoretical and mostly an impassioned argument for hope for the future based on the best ideas of the American Project.