Rat-Fucker Rashomon: Four Stories about Roger Stone (Introduction)

As background for some other things and because I’m a former scholar of narrative, I want to lay out the four different stories that have been told of Roger Stone’s actions in 2016 and after:

- The Mueller Report

- The Stone prosecution

- The SSCI Report

- The affidavits from the investigation

One day there might be a fifth story, the investigative records, but those are still so redacted (and the subjects were such committed liars) to be of limited use right now, so while I will integrate them and other public records into this series, I won’t treat them as a separate story.

I observed in this post that a September 2018 affidavit revealed that the Stone indictment and trial were, in part, investigative steps in a larger investigation, an investigation that Bill Barr appears to have since substantially killed. The affidavit asked for (and received) a gag because, it explained, investigators were trying to keep Stone from learning that the investigation into him was broader than he thought.

It does not appear that Stone is currently aware of the full nature and scope of the ongoing FBI investigation. Disclosure of this warrant to Stone could lead him to destroy evidence or notify others who may delete information relevant to the investigation.

Partly, the larger investigation must have been an effort to determine — and if possible, obtain proof beyond a reasonable doubt — of how Stone optimized the release of (at least) the Podesta emails. I think the evidence shows Stone did partly optimize the release, though I also believe doing so served as much to compromise Stone and others as to help Trump get elected. In an unreliable Paul Manafort interview, Trump’s former campaign chair describes a conversation (this may have taken place in spring 2018, during a period when Manafort unconvincingly claims he was not engaged in concocting a cover story with his lifelong buddy) where Stone clarified that he was just a conduit in the process of optimizing the Podesta release, not the decision maker.

Stone said to Manafort that he was not the decision maker or the controller of the information. Stone said he may have had advance knowledge, but he was not the decision maker. Stone was making clear to Manafort that he did not control the emails or make decisions about them. Stone said he received information about the Podesta emails but was a conduit, not someone in a position to get them released.

That’s Stone and Manafort’s less damning explanation, that Stone did have advance knowledge but didn’t control the process! It may also be true, though Stone likely believed he was controlling things in real time, when he was making stupid promises. Being a reckless rat-fucker can make a guy vulnerable to rat-fuckery himself.

I also believe that prosecutors did confirm how Stone got (information on) the emails and what stupid promises he had to make to get them, though not until after Stone was charged in his cover-up and probably not beyond a reasonable doubt. But, likely for a variety of reasons, they never told us that in any of the four stories that have been released about Stone.

So I want to examine what story each of the four narratives tell, because what an author withholds [wink] is always at least as interesting as what storyline the author uses to engage her readers.

The Mueller Report

All these stories are constrained, in part, by their genre.

For example, legally, the Mueller Report fulfills a requirement of the regulation under which Mueller was appointed.

Closing documentation. At the conclusion of the Special Counsel’s work, he or she shall provide the Attorney General with a confidential report explaining the prosecution or declination decisions reached by the Special Counsel.

You finish your work, and you tell the Attorney General overseeing your work whom you charged, whom you didn’t, and why. The Mueller Report, consisting of two volumes and some appendices laying out referrals from the investigation itself, therefore had to tell a story to support these decisions:

- To charge a bunch of IRA trolls but none of the Americans unwittingly cooperating with them

- To charge a bunch of Russian intelligence officers but not WikiLeaks or Roger Stone (though note that Rod Rosenstein has said the WikiLeaks investigation always remained at EDVA)

- Not to charge Don Jr and Stone for accepting or soliciting illegal campaign donations from foreigners

- Not to charge a bunch of Trumpsters for their sleazy influence peddling

- To charge a bunch of Trumpsters with lying and (in the case of Manafort and Gates) various kinds of financial fraud, but not to charge other Trumpsters for equally obvious lying

- Effectively (and this is my opinion), to refer Trump to Congress for impeachment

- To refer a bunch of other matters, ranging from Trumpsters’ financial fraud, George Nader’s child porn (though given the releases from the other day, it’s not clear that’s formally in the report), and a number of counterintelligence matters, for further investigation

That’s not all. Technically, one investigation into someone either close to or Trump himself wasn’t even done at the time Mueller finished. Documents show a campaign finance investigation–AKA bribery–involving a bank owned by a foreign country was ongoing; Bill Barr has recently publicly bitched about the legal theory behind the investigation (one SCOTUS approved) and it has been closed. And, significantly, for the purpose of this series, Mueller had not obtained Stone aide Andrew Miller’s testimony when the Report got written either, though at the minute Miller agreed to testify, Mueller was giving a presser closing up shop, presumably (though not definitely) making Miller’s testimony part of the ongoing investigation related to Stone.

Aside from those two details, the story the Mueller Report has to tell has to explain those prosecutorial decisions. For the sake of this series, then, the story has to tell why Stone wasn’t charged for soliciting illegal campaign donations from WikiLeaks, why he was charged for lying to obscure who his go-between was and whether he had discussed all that with Trump and others on the campaign, and why Trump should be impeached for his promises to pardon Stone (among others) for covering up what really happened in 2016.

Significantly for this story, Stone was not charged because he lied about having a go-between (he lied to Congress to cover up who it was), nor was he charged for any actions he took with his go-between to get advance information. I’m not certain, but such charges may actually not be precluded by double jeopardy; if not, this story may have been written to ensure no double jeopardy attached. In any case, we shouldn’t expect details of his go-between to be fully aired in the report (or encompassed by it), because it was not a prosecutorial decision that needed to be explained.

The timeline of the Stone part of this story starts in early June 2016, and (for the main part of his story) ends the day the Podesta emails got released, October 7, leaving out a bunch of Stone activities that were key prongs of the investigation.

The Stone prosecution

The story told by the Stone prosecution unsurprisingly adopts the same general scope as the Mueller Report.

As noted above, the government took a number of investigative steps in 2018 that they kept secret from Stone, explicitly because they wanted Stone to continue to believe he was only under investigation for his lies about his claims about having a go-between with WikiLeaks. Because of that, I think the story the Stone prosecution told is best understood as a way to use the prosecution to advance a larger investigation, without compromising the rest of it. As such, it makes the way in which prosecutors controlled this narrative all the more interesting. That dual objective — advancing the larger investigation but keeping secrets –meant that prosecutors needed to provide enough detail to win the case — possibly even to get testimony about specific details to achieve other objectives in their investigation — but not disclose details that would give away the rest or require unreliable witnesses.

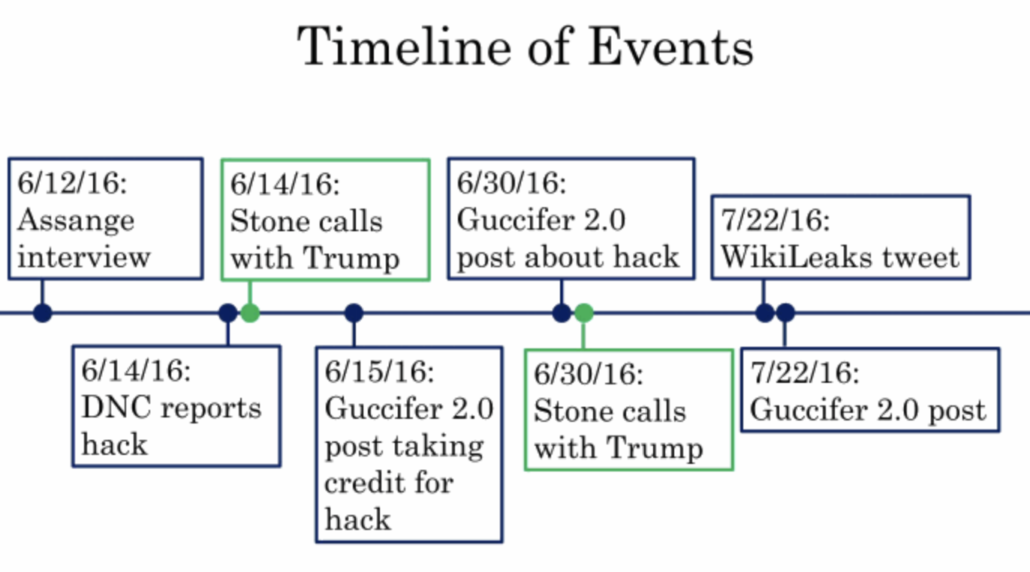

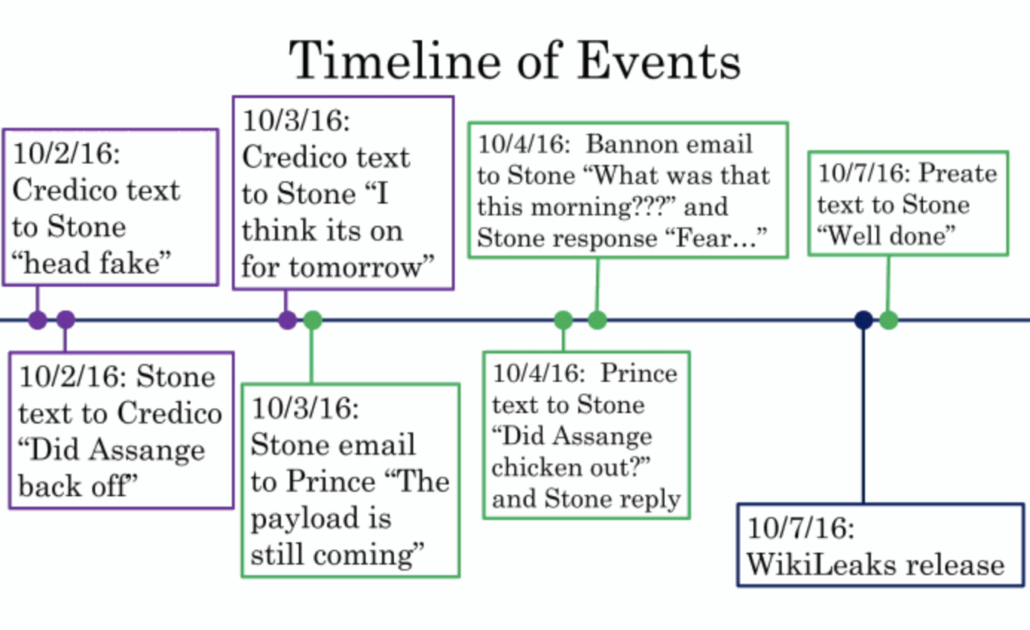

The Stone prosecutors provided us a handy timeline to show the scope of its story, split into two sections. The first starts with Assange’s promise of additional Hillary files on June 12, 2016 and ends on October 7, 2016.

While Rick Gates did testify that Stone predicted a WikiLeaks drop even before June 12, his testimony focused far more closely on discussions they had in the wake of the June 14 DNC announcement they’d been hacked. So the prosecution left out interesting details about what Stone was up to in spring 2016.

By ending the earlier, election-related timeline on October 7, prosecutors didn’t include a presumed Stone meeting with Trump on October 8 or the evidence that he and Corsi had advance knowledge of certain Podesta files, which became clear around October 13, to say nothing of what happened in the days after the election.

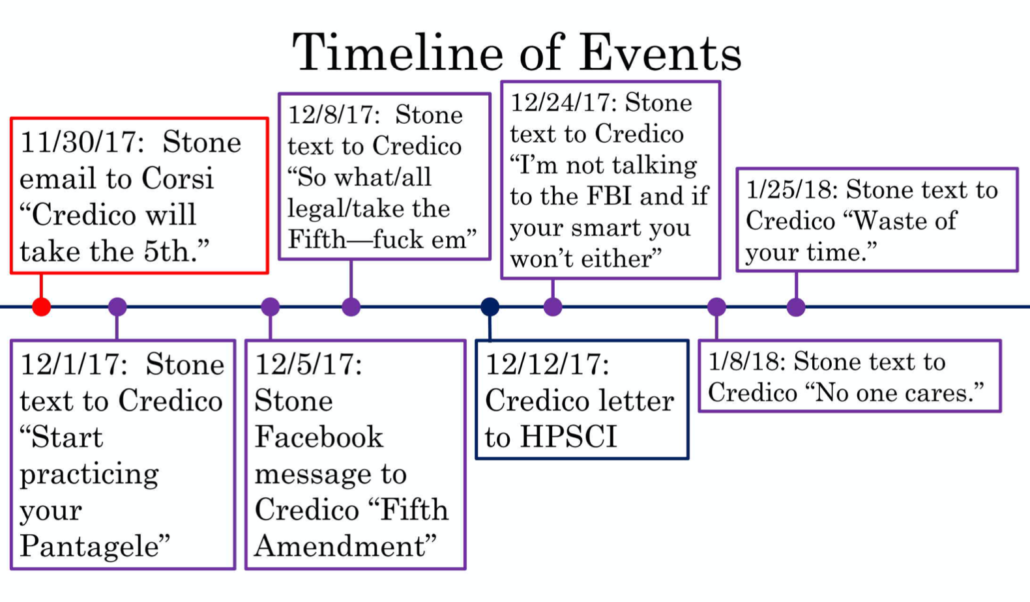

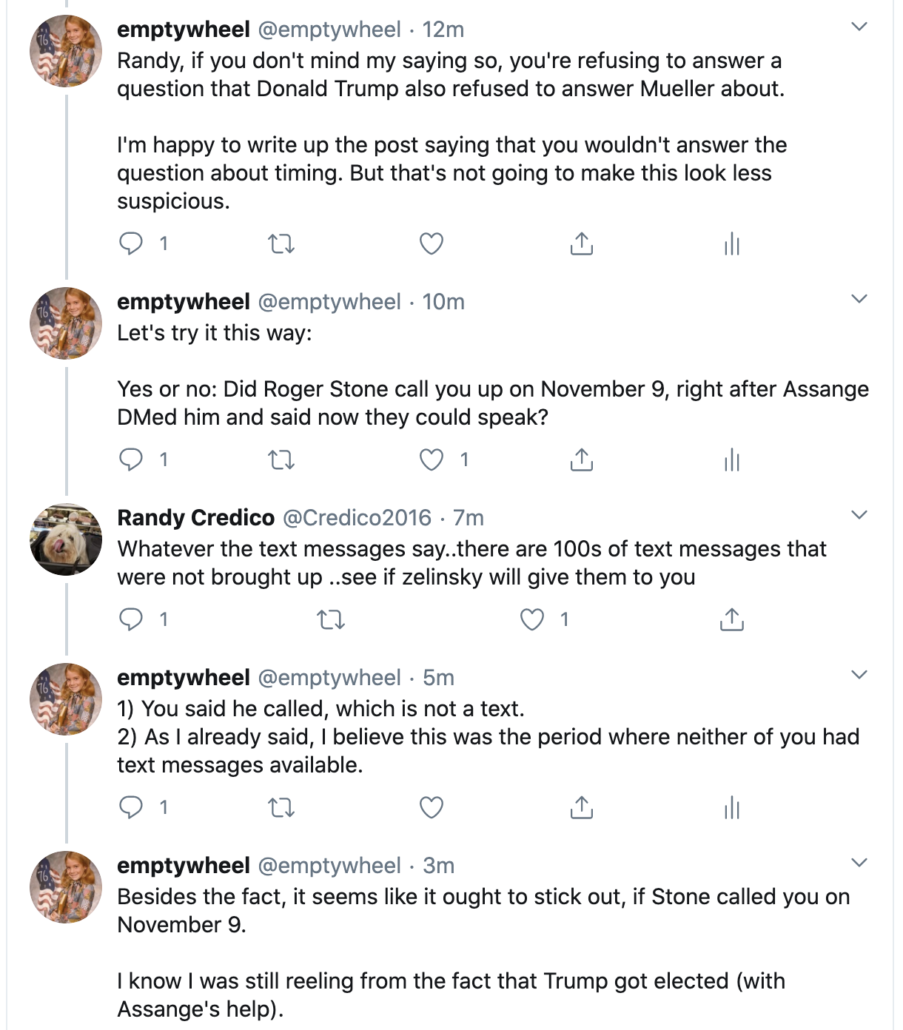

Then, the prosecution adopted a later timeline covering obstruction and witness tampering. It starts on January 6, 2017 and — at least on this timeline — goes through January 28, 2018 (though FBI Agent Michelle Taylor introduced evidence and Randy Credico testified to events that took place after that date).

That’s the scope of the story: an abbreviated version of 2016, starting after Stone first starting claiming to have advance warning of the email dumps, and ending well before things started to get interesting in the lead-up to and aftermath of the election.

A simplified version of the plot this story tells is how Stone used Credico to make sure no one would look too closely at what he had been up to with Corsi.

The SSCI Report

As I said, most of these stories were dictated, in part, by genre and a specific goal. Prosecutors writing the Mueller Report could only tell a story that explained prosecutorial decisions, and in this case, they had an ongoing investigation to protect (which Barr appears to have since substantially killed). Prosecutors scoping the Stone prosecution only had to present enough evidence to get their guilty verdict, and presumably didn’t want to produce evidence that would disclose the secrets they were trying to keep or expose a weakness in an otherwise airtight case. As for the warrants, every affidavit an FBI agent writes notes that they are including only as much as required to show probable cause. With a caveat laid out below, the FBI agents wouldn’t want to include too much for fear of giving defendants reason to challenge the warrants in the future. So the Stone affidavits, like all probable cause affidavits, are an exercise in careful narrative, telling a story but not telling too much.

Thus, the SSCI Report (clocking in at almost 1,000 pages) is the only one of these four stories that even pretends to be revealing all it knows. But it also didn’t try to tell the whole story. It limited the scope of the investigation in various ways (most notably, by refusing to investigate Trump’s financial vulnerabilities to Russia). And over and over again, the SSCI Report pulled punches to avoid concluding that the President is a glaring counterintelligence risk. The imperative of protecting the President (and getting Republican votes in Committee to actually release it) affected the way SSCI told its story in very tangible ways.

Because it is a SSCI Report, this story has a ton of footnotes which are (as they are in most SSCI Reports) a goldmine of detail. But the decision of what to put in the main body of a story and what to relegate to a footnote is also a narrative question.

Importantly, SSCI had outside limitations on its investigation — and therefore its story — that the FBI did not have. Rick Gates, Jerome Corsi, and Paul Manafort largely invoked the Fifth Amendment. Stone refused to testify. SSCI only received a limited subset of Mueller’s 302s, and none pertaining to the GRU investigation. SSCI had limited ability to demand the content of communications. The White House and the Trump Org withheld documents, even some documents they otherwise provided to Mueller. Plus, the version of the report we have is heavily redacted (including much of the discussion about WikiLeaks), sometimes for classified reasons but also sometimes (if you trust Ron Wyden’s additional views) to protect the President. That means we don’t even get the full story SSCI told.

Nevertheless, while SSCI left out parts of the story that the FBI seems to have considered important, the SSCI Report also includes a lot that DOJ and FBI had to have known, but for reasons that likely stem, in part, from the stories they wanted or were obligated to tell, they chose not to disclose. That makes the SSCI Report really useful to identify what must be intentional gaps in the other stories.

Like the Mueller Report (in part because it relied heavily on it), the story that the SSCI Report tells about Stone adopts an uneven timeline, narrowly focusing on Stone’s election season activities even while for others it adopts a broader timeframe. More generally, though, the SSCI Report tells a story about the dangerous counterintelligence threats surrounding the President, while stopping short of fully considering how he is himself a counterintelligence threat.

The warrant affidavits

As noted, FBI warrants deliberately and explicitly try to find a sweet spot, establishing probable cause but not including stuff that either might be challenged later or might give away investigative secrets. That said, Andrew Weissmann’s book reveals that Mueller’s team included more detail than needed in affidavits to provide a road map if they all got fired.

We also realized we could use the courts as a kind of external hard drive to back up our work. The applications for search warrants we filed with the court only had to set out a minimum of facts from which the court could find probable cause—a fairly low standard. But by packing those documents with up-to-date details of our investigation, we could create a separate record of our activities—one that would be deposited securely in the judicial system, beyond the reach of the Department of Justice, the White House, or Congress. (Putting such a substantial record before the court had the added benefit of eliciting quick rulings on our applications and demonstrating that we were not tacking too close to the line in establishing the necessary probable cause.)

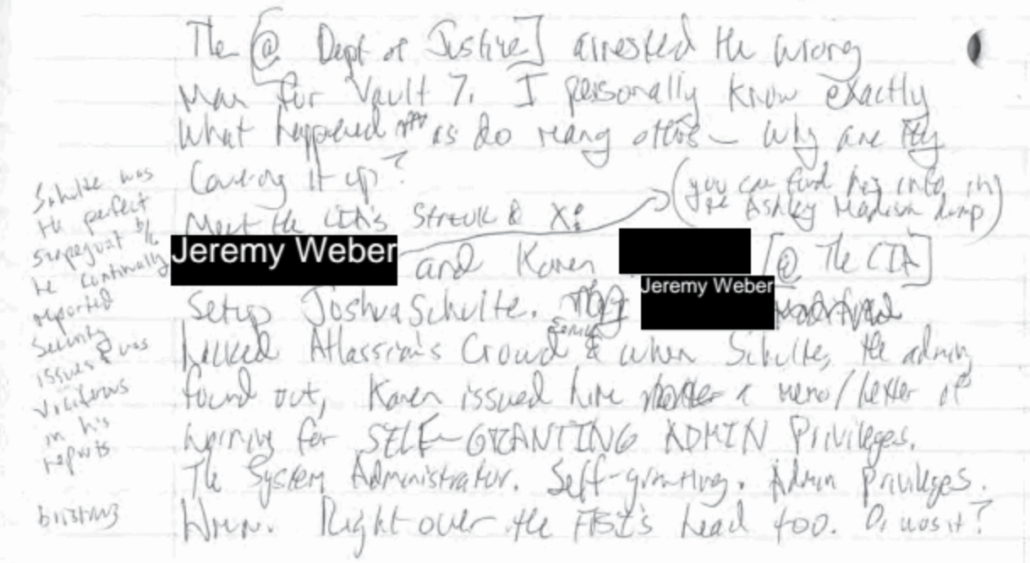

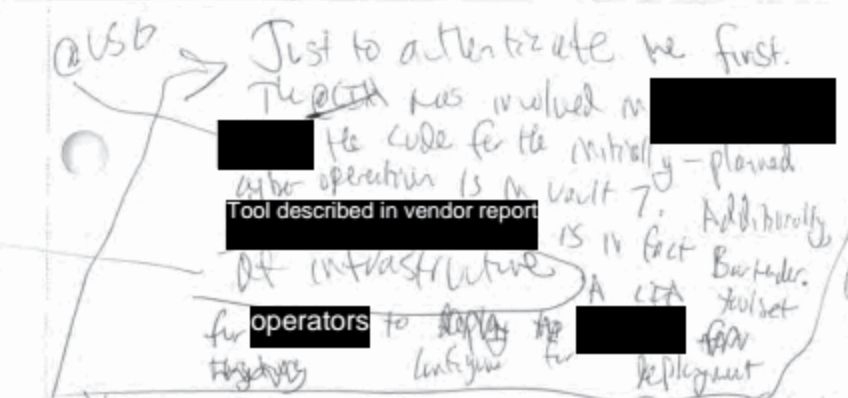

The affidavits in the Stone case — written by at least 5 different FBI agents — actually tell two stories: The first is a narrative of how allegations were made and then removed, often for emphasis but also, probably in some cases, because suspicions were answered. The second is an evolving narrative of some of the core pieces of evidence that Stone did have advance notice of the releases, and so may have had legal liability — either as a co-conspirator, or someone who abetted the operation — for the hack-and-leak. It came to double in on itself, investigating Stone’s extensive efforts to thwart the investigation. Near the end of the investigation, that story came to incorporate Foreign Agent charges (though it’s not entirely sure how much Stone, or other people like Assange, are the target of those warrants, and virtually all that story is redacted). I lay out how these two narratives intersect here.

For some of the investigation, the affidavits adopted a timeline starting in June 2015 (when Stone worked on the Trump campaign) and continuing through the election, but ultimately that timeline extended through to the present in 2018 and 2019, ostensibly to support the obstruction investigation.

The gaps

The differences between the stories may be easiest to identify by observing what each leaves out. Each of these stories leaves out some pieces of evidence of one or more of the following:

- The extent and nature of Stone’s provable interactions about WikiLeaks with Trump: While all of these stories do include evidence that Stone kept Trump apprised of his efforts to optimize the Podesta release, the SSCI Report — completed without Trump’s phone records or those of many others, with a very limited set of witness 302s, and limited power to access evidence of its own — describes damning interactions that none of the other stories do.

- The extent to which either Corsi or Stone succeeded in dictating the release of the Podesta emails on October 7, 2016 and why: Several stories consider only whether Corsi managed to get WikiLeaks to drown out the Access Hollywood video, without considering whether Stone did.

- What Stone and Corsi did with advance knowledge that WikiLeaks would release information on John Podesta’s ties with Joule holdings: Manafort’s unreliable testimony (and a bunch of other evidence) seems to confirm that Stone and Corsi had at least advance notice of, if not documents themselves, on Podesta’s ties with Joule Holdings that were later released by WikiLeaks. Only one of these four stories — the affidavits — include this process as a central story line, but it’s one way to show that the rat-fucker and the hoaxster did have advance knowledge (and show what their fevered little brains thought they were doing with it).

- Proof that Stone had foreknowledge: While much of this is inconclusive, the affidavits make it clear that investigators believed Stone’s knowledge went beyond and long preceded what Corsi obtained in early August 2016. Once you establish that foreknowledge, then all question of Corsi versus Credico is substantially meaningless window-dressing (albeit convenient window dressing if you’re trying to hide a larger investigation).

- Steve Bannon’s knowledge of and possible participation in Stone’s schemes shortly after he came on as campaign manager: The government almost certainly has grand jury testimony laying this out. But we’ve only seen glimpses of what happened after Stone wrote Bannon and floated a way to win the election the day he came onto the campaign, and not all of these stories were even curious about what happened.

- Stone’s social media efforts to undermine the Russian attribution: I’m agnostic at this point about the significance of investigators’ focus on Stone’s efforts to undermine the Russian attribution for the operation, but some stories cover it and others ignore it conspicuously.

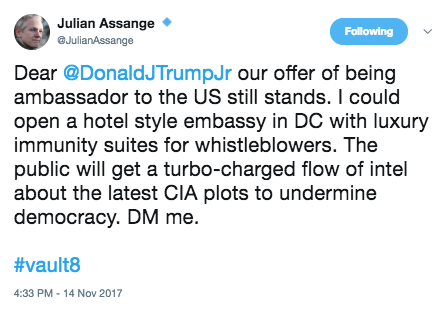

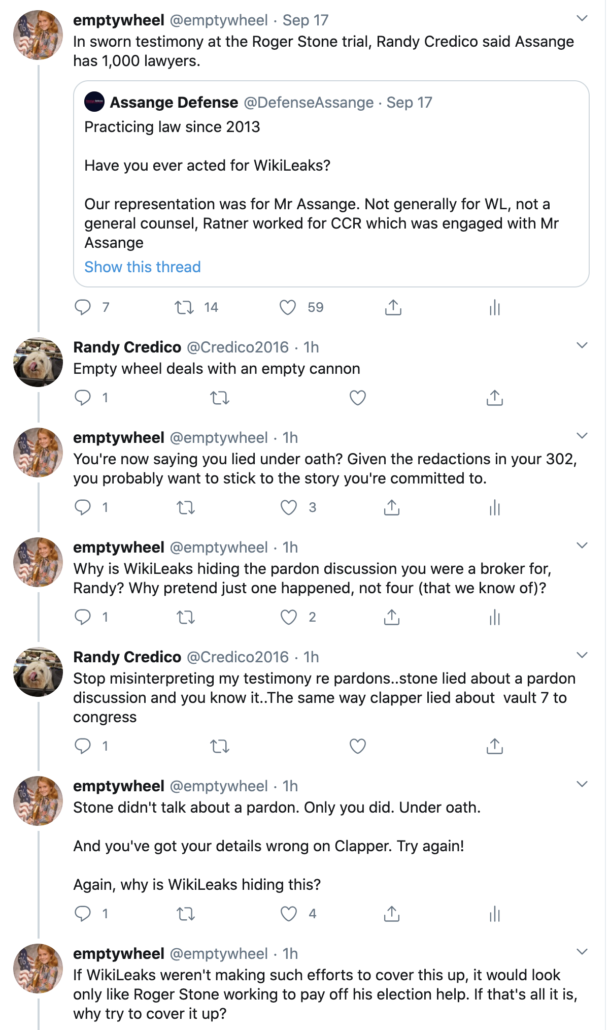

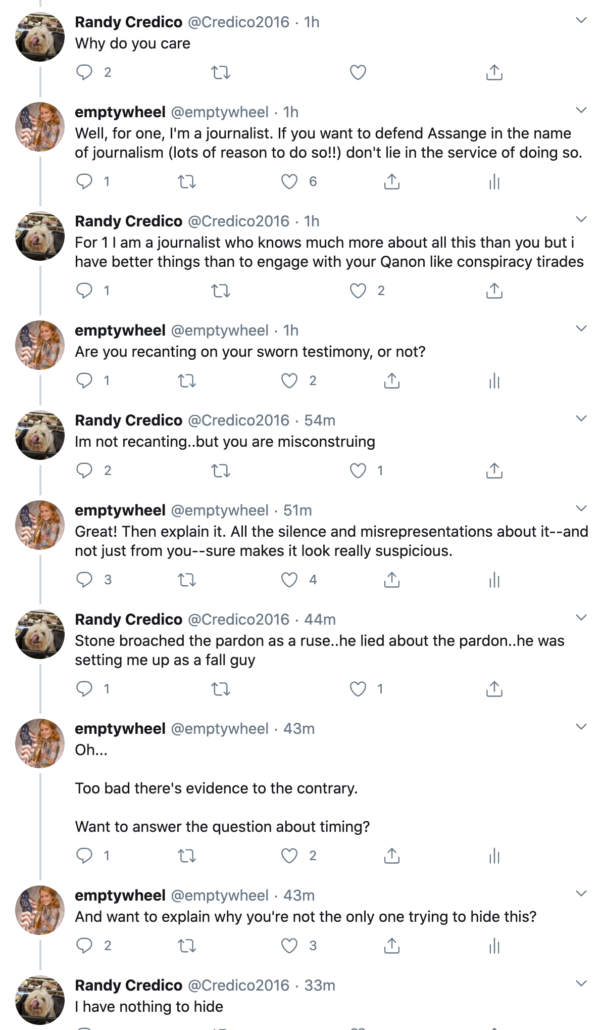

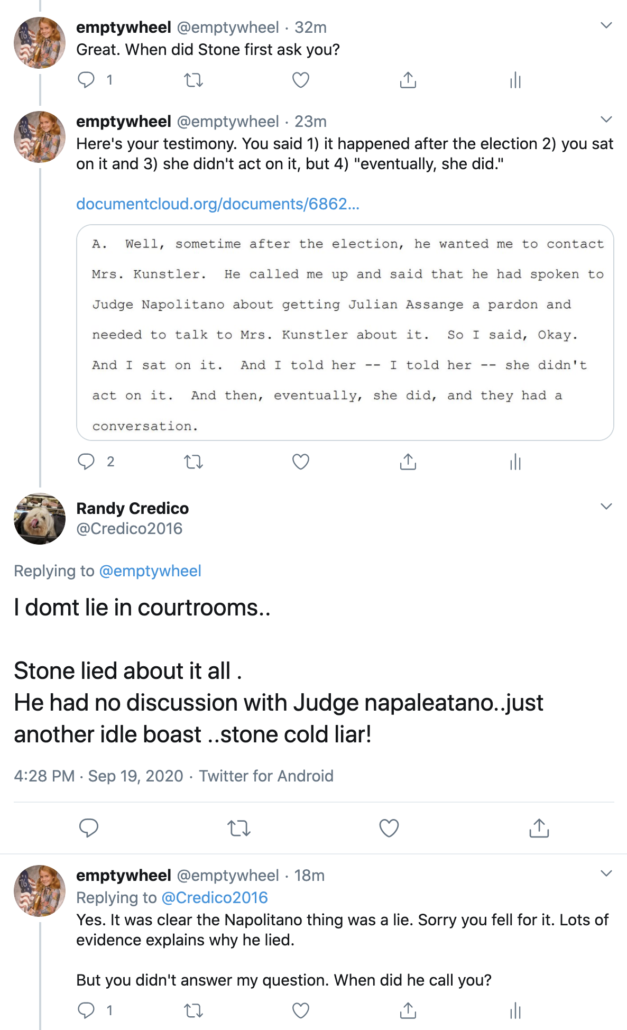

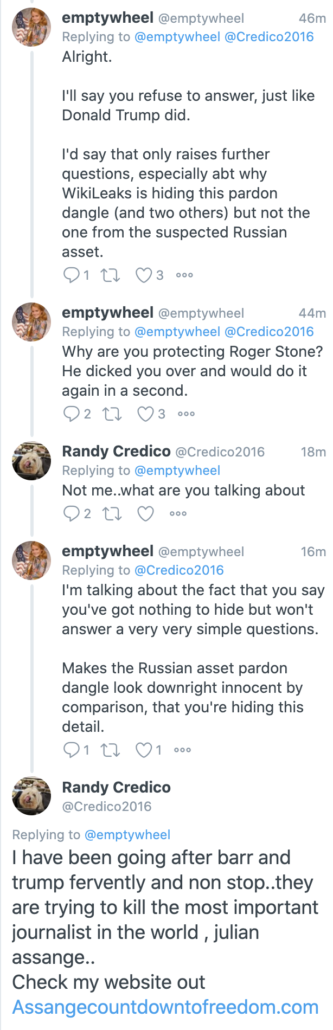

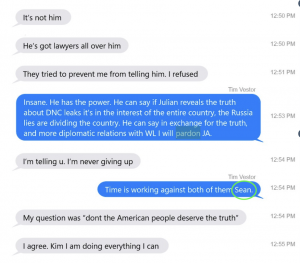

- Stone’s extended effort to get a pardon for Julian Assange: It is a fact that Stone pursued a pardon for Julian Assange after Trump won. While it’s not yet proven whether Stone reached out to WikiLeaks on or even before November 9 or waited until days later, several of these stories incorporate details of that effort. Others ignore it.

- Stone’s interactions with Guccifer 2.0: This story is virtually identical, albeit with additive bits, in three of the four stories. It is — almost — entirely absent from the prosecution.

The Manafort-Stone connection

One other detail to consider as you look at the different stories told here: Not a single one of them treats Manafort and Stone as a unit or a team. Partly this is just convenience. It’s hard to tell a story with two villains, and there is so much dirt on both Manafort and Stone, there’s more than enough material for one story for each. We also know that from the very beginning of the investigation, the Mueller team largely kept these strands separate, a team led by Andrew Weissmann focusing on Manafort and a team led by Jeannie Rhee focusing on Russian outreach (though 302s and other documents show that Rhee definitely participated in both, and Weissmann describes working closely with Rhee in his book).

But Roger Stone played a key role in getting Manafort hired by the Trump campaign. They were friends from way back. They used each other to retain a presence on the campaign after they got booted. Stone made reckless efforts to obtain the Podesta files partly in a bid to save Manafort. So while it’s easy to tell a story that keeps the Manafort corruption and the Stone cheating separate, that may not be the correct cognitive approach to understand what happened.

None of these stories tell the complete story. Most deliberately avoid doing so, and the one that tried, the SSCI Report, stopped short of telling all that’s public and didn’t have access to much that remains secret. Reading them together may point to what really happened.

Links to all posts in the series

- While the Mueller Report made it clear Trump’s pardon dangles to keep details of his conversations with Roger Stone secret amounted to obstruction, it didn’t tell just just how many conversations they had

- Rather than telling us whether, how, and why Roger Stone optimized the release of John Podesta’s emails on October 7, 2016, the Mueller Report instead gave us Jerome Corsi slapstick

- Just one story presents the significant amounts of evidence suggesting that on August 14, 2016, when he started a file called “Podesta,” Jerome Corsi had or knew the contents of the Podesta files that would become public on October 11, 2016

- The later stories focus on Podesta, rather than the evidence that Stone learned of the hack-and-leak while the burglary was still ongoing

- Stone pitched both Manafort and Bannon on a way to win ugly–but none of the Stone stories tell us what that was

- Trolling for Russia

- The “highest levels of government” attempt to shut down an investigation into Julian Assange

- There’s reason to believe Guccifer 2.0 was Stone’s go-between to WikiLeaks