Scooter Libby, Whom Trump Pardoned, Serves as Precedent for the CIPA Challenge His Prosecution Presents

If and when former President Trump goes on trial, the Classified Information Procedures Act will govern what information gets submitted at trial and in what form. I wrote about CIPA in conjunction with the Igor Danchenko case here. Former National Security Division prosecutor David Aaron wrote about it the other day.

I’d like to give three examples of what documents that have gone through the CIPA process look like.

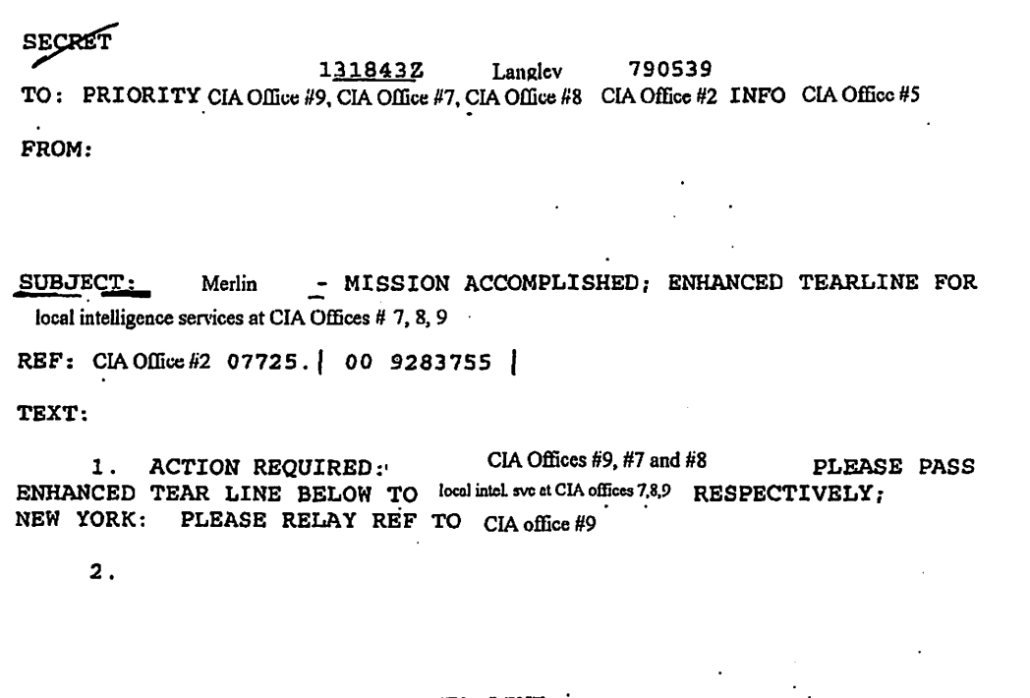

First, here’s one of the many CIA cables introduced at Jeffrey Sterling’s trial (here’s a larger set). Sterling was convicted of leaking details about a scheme to use a former Russian nuclear scientist to deal fake blueprints to Iran in an attempt to bollox their nuclear program. The cables would include substitutions for all the organizational details of how CIA works, as well as for the names of the Russian — Merlin — and all the covert CIA officers involved. Entire paragraphs that weren’t crucial to the meaning of the document were redacted.

This particular document was 15 years old when it was used at trial. Most if not all of the Sterling exhibits were classified Secret.

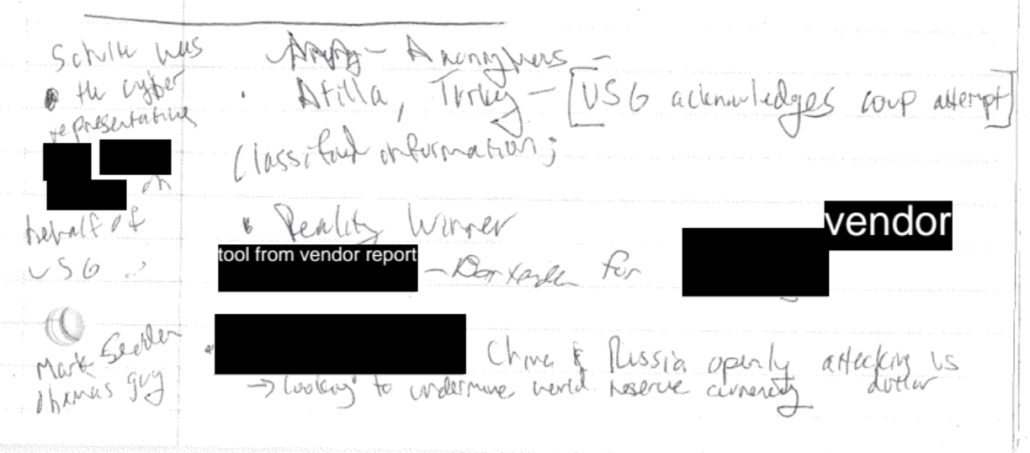

This exhibit includes the parts of Josh Schulte’s prison notebook introduced at trial. This was tied to the allegation that he was launching an Information War from jail, planning to leak further classified information to damage the CIA.

The government was able to substitute the name of a cybersecurity company that had IDed one of the CIA’s hacking tools, so as to avoid confirming that the tool referred to as Bartender in the WikiLeaks release was the malware discussed in the vendor report. But several other things were entirely redacted — such as details of the role that Schulte played at the CIA.

Some of these redactions cover other information — such as his privileged material or stuff that’s particularly inflammatory.

Schulte wrote these notes in 2018; they were first introduced for his 2020 trial, then again for his trial last year.

The case that may present the most analogous challenges to a trial against Trump is the Scooter Libby case, which — like the documents charged against Trump — involved a lot of classified communications to the White House. Here are the exhibits used in his 2nd Grand Jury appearance, at which he lied to cover up the orders Dick Cheney gave him.

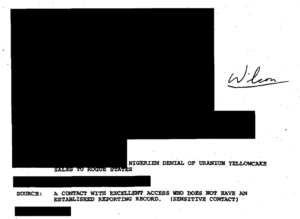

Many of these are CIA documents from which the classification markings and entire sentenced were redacted. Like two of the exhibits charged against Trump, these have hand-written notes — sometimes Libby’s, sometimes Cheney’s — which were important to the case. One HUMINT report involving Joe Wilson redacted all the front-matter, including the classification marks (in this case, the notation of Wilson’s name was the important bit).

Even still, the vast majority of the documents introduced at trial were still just classified Secret, not Top Secret with compartments like most of the documents charged against Trump.

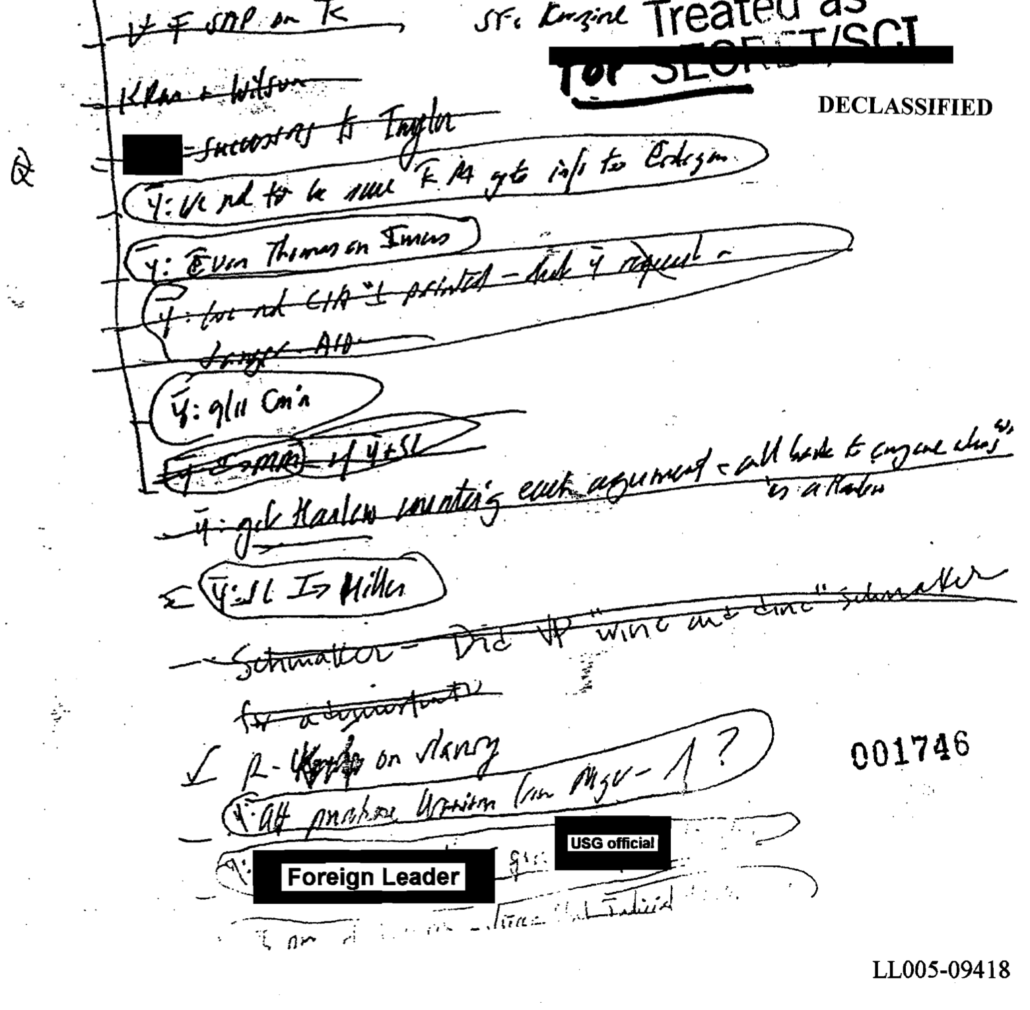

The exceptions were often Libby’s notes of Daily Briefings (including PDBs), which he used as part of a gray-mail campaign to try to make the case impossible to try. Though they didn’t have any classification marks (as is true of a document charged against Trump), they were treated as TS/SCI.

Here’s one example of from Libby’s own notes:

The vast majority of this had to be declassified because it was central to the defense Libby was mounting. Just the Foreign Leader and the US official were masked.

The Libby documents are similar to those charged against Trump in another way. These were just 4 years old when presented at trial. If Trump were to go to trial next year, the most recent documents, from 2020, would be four years old.

These cases are all in different circuits than Trump would be prosecuted in. Nevertheless, given the scant number of CIPA cases, it’s possible that the case of Josh Schulte — about whose case was one of the first times Trump shared classified information — and Scooter Libby, whom Trump pardoned, will serve as precedents for his prosecution.