Yarvin Explains Why He’s Writing

The introduction to this series should be read first. It has the index to all posts in this series.

Yarvin explains why he’s writing in this post. He opens with a poem by the Greek poet C. P. Cavafy, Que Fecit — Il Gran Rifuto, which, roughly translated, is He Who Makes The Great Refusal. Here’s the text:

For some people the day comes

when they have to declare the great Yes

or the great No. It’s clear at once who has the Yes

ready within him; and saying it,he goes forward in honor and self-assurance.

He who refuses does not repent. Asked again,

he would still say no. Yet that no—the right no—

undermines him all his life.

Translation by Keeley and Sherrard. Writing in 2007, Yarvin says:

Journalists and professors are all associated with what is essentially one large institution, the press and university system. There are few, if any, ideological quarrels between major universities, or between universities and mainstream journalists.

He says that they all agree on practically everything. The differences between universities are marginal, as are the differences between professors at these institutions, and the differences between journalists. He doesn’t agree with this consensus.

He notes the recent rise of right-wing think tanks, like the Heritage Foundation , the Cato Institute, and the Manhattan Institute, but these are weak, and in no way competitive intellectually with the universities and their acolytes.

He says he’s trying to create an entirely new perspective. He reads Cavafy’s poem first as a paean to the dominant system, and second to the value in dissent. The dominant system rewards joiners, and accomplishes many things. A world of refusers would be a horrible thing. But he wants to be the one who refuses to participate in the Great Consensus, he wants to create an entirely new perspective.

What I’m trying to assemble here at UR is a view of the world we live in that is genuinely alien—at least, as genuinely alien as I can make it. By “alien” I just mean strange, different, or unfamiliar. …

Snip

An alien perspective is useful because it is not, at least not obviously, influenced by the ideas that are loose in the world today.

He says that there are two ways to do this. One is to start from scratch. This approach opens the door to appalling mistakes. One alternative is paleoconservativism. This is perhaps the most alien perspective on our times that he can think of.

Paleoconservatives evaluate the present by the standards of the past. He claims that their views aren’t taught anywhere, there is no education grounded in paleoconservatism. He doesn’t like present-day paleoconservatives, though. He thinks they’re too clubby, too esoteric, and probably too much in love with past regimes. Yarvin isn’t interested in recreating the Holy Roman Empire, or the Byzantine Empire.

He wants to look at 2007 the way people in 2107 do. In the end, he writes because he enjoys doing it and a bunch of people talked him into writing.

Discussion

1. I’m not wiling to read any posts based on Dungeons and Dragons. Or religion. And no more The Matrix, either. Checking ahead, no comparisons between humans and computer hardware.

2. I am sympathetic to the urge to look for different perspectives. I imagine that’s something everyone does when they’re dissatisfied with the status quo; and that academics do it in search of advancement. I’m also sympathetic to the idea of reading older books. Wisdom isn’t the special province of the present.

3. I don’t think it’s possible to start from scratch, as Yarvin claims he wants to do. There is no such place.

I also don’t think that we benefit from considering the present through the lens of the past. The wisdom of the past was directed at the conditions that existed when it was generated, and much of it was dreamed up to support the then status quo. We have to examine each idea in light of our present situation before we try to use it.

That means we have to identify the problem we want to solve carefully. Yarvin hasn’t precisely stated the problem that drives him to consider paleoconservatism. Based on what I’ve covered so far, I’d suggest some possibilities:

a. The people with power are unable to exercise all their power.

b.. Governmental regulation and public opinion are too cumbersome, and should be removed.

c. Democracy can’t solve irreconcilable differences, so civil war is inevitable.

d. The only serious problem facing our society is violence against person and property. Democracy won’t solve that problem so we need another system.

e. There’s something, as yet undefined, wrong with the way the universities and reporters pursue truth.

As to e., there is a consensus at the root of our education system, one shared with all academics and more widely across society. It’s what Jonathan Rauch calls the epistemic regime, the system we use to construct knowledge. I discuss it here, and in the three posts in that series.

We also use that system to construct and evaluate solutions to problems. Yarvin’s Heritage Foundation and other think tanks aren’t trying to solve problems. They exist to create justifications for undoing solutions currently in place as demanded by their donors. They have no new solutions, and their use of the epistemic regime is intellectually suspect.

Yarvin is toying with the idea of rejecting the epistemic regime but has nothing to suggest as a replacement.

4. As I wrote in the introduction to this series, I’m trying to take this guy seriously. That’s not easy. I have trouble ignoring the possibility that Yarvin is just a contrarian, a jolly gadfly, skittering about puncturing platitudes with outrageous claims like this: “Safeway will sell you a whole, salted rhinoceros head before Harvard will teach you that Lincoln was a tyrant.”

5. Yarvin seems to think that scholars are all liberals. Whatever. I don’t suppose Yarvin has read Discipline and Punish by Michel Foucault. I wonder if he would say that Foucault was a liberal, or that he was part of the consensus he so dislikes?

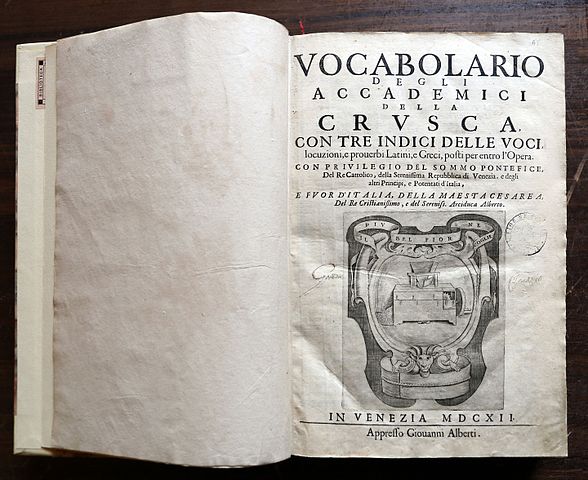

6. Finally, a word about the Cavafy poem. Here’s the first paragraph of the Wikipedia entry on the title of the poem:

The great refusal (Italian: il gran rifiuto) is the error attributed in Dante’s Inferno to one of the souls found trapped aimlessly at the Vestibule of Hell, The phrase is usually believed to refer to Pope Celestine V and his laying down of the papacy on the grounds of age, though it is occasionally taken as referring to Esau, Diocletian, or Pontius Pilate, with some arguing that Dante would not have condemned a canonized saint. Dante may have deliberately conflated some or all of these figures in the unnamed shade.

The canonized saint in ths passage is Celestine V. Here’s the Dante line:

After I had identified a few,

I saw and recognized the shade of him

who made, through cowardice, the great refusal.

Dante says the speaker of the Great Refusal is a coward. Cavafy thinks that the great refusal is right for some people in some cases. The world needs people who refuse to accept the dominant social narative. Yarvin makes a point of saying that he’s made the right decision for himself.