In this Xitter thread, I went through everything that had been added or removed from the superseding indictment against Trump, based on this redline. The changes include the following:

- Removal of everything having to do with Jeffrey Clark

- Removal of everything describing government officials telling Trump he was nuts (such as Bill Barr explaining that he had lost Michigan in Kent County, not Wayne, where he was complaining)

- Removal of things (including Tweets and Trump’s failure to do anything as the Capitol was attacked) that took place in the Oval Office

- Addition of language clarifying that all the remaining co-conspirators (Rudy Giuliani, John Eastman, Sidney Powell, Kenneth Chesebro, and — probably — Boris Epshteyn) were private lawyers, not government lawyers

- Tweaked descriptions of Trump and Mike Pence to emphasize they were candidates who happened to be the incumbent

- New language about the treatment of the electoral certificates

Altogether, the changes incorporate not just SCOTUS’ immunity decision, but also the DC Circuit’s Blassingame decision deeming actions taken as a candidate for office are private acts, and SCOTUS’ Fischer decision limiting the use of 18 USC 1512(c)(2) to evidentiary issues.

The logic of Blassingame is why Jack Smith included these paragraphs describing that Trump and Pence were acting as candidates.

1. The Defendant, DONALD J. TRUMP, was a candidate for President of the United States in 2020. He lost the 2020 presidential election.

[snip]

5. In furtherance of these conspiracies, the Defendant tried–but failed–to enlist the Vice President, who was also the Defendant’s running mate and, by virtue of the Constitution, the President of the Senate, who plays a ceremonial role in the January 6 certification proceeding.

As I’ve said repeatedly, it’s not clear that adopting the Blassingame rubric will work for SCOTUS, even though they did nothing to contest this rubric.

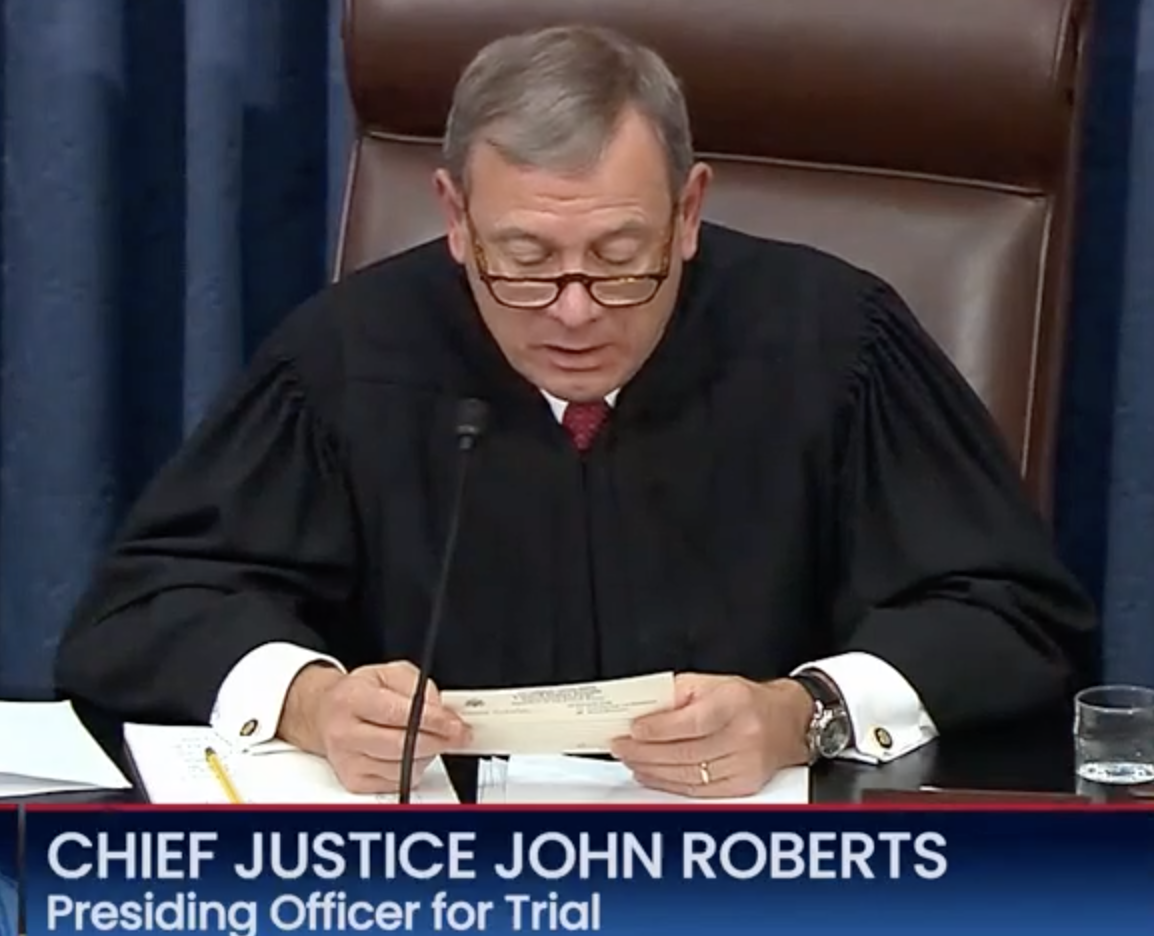

That’s because Chief Justice Roberts used Pence’s role as President of the Senate to deem his role in certification an official responsibility, thereby deeming Trump’s pressure of Pence an official act. Smith will need to rebut the presumption of immunity but also argue that using these conversations between Trump and Pence will not chill the President’s authority.

Whenever the President and Vice President discuss their official responsibilities, they engage in official conduct. Presiding over the January 6 certification proceeding at which Members of Congress count the electoral votes is a constitutional and statutory duty of the Vice President. Art. II, §1, cl. 3; Amdt. 12; 3 U. S. C. §15. The indictment’s allegations that Trump attempted to pressure the Vice President to take particular acts in connection with his role at the certification proceeding thus involve official conduct, and Trump is at least presumptively immune from prosecution for such conduct.

The question then becomes whether that presumption of immunity is rebutted under the circumstances. When the Vice President presides over the January 6 certification proceeding, he does so in his capacity as President of the Senate. Ibid. Despite the Vice President’s expansive role of advising and assisting the President within the Executive Branch, the Vice President’s Article I responsibility of “presiding over the Senate” is “not an ‘executive branch’ function.” Memorandum from L. Silberman, Deputy Atty. Gen., to R. Burress, Office of the President, Re: Conflict ofInterest Problems Arising Out of the President’s Nomination of Nelson A. Rockefeller To Be Vice President Under the Twenty-Fifth Amendment to the Constitution 2 (Aug. 28, 1974). With respect to the certification proceeding in particular, Congress has legislated extensively to define the Vice President’s role in the counting of the electoral votes, see, e.g., 3 U. S. C. §15, and the President plays no direct constitutional or statutory role in that process. So the Government may argue that consideration of the President’s communications with the Vice President concerning the certification proceeding does not pose “dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.” Fitzgerald, 457 U. S., at 754; see supra, at 14.

At the same time, however, the President may frequently rely on the Vice President in his capacity as President of the Senate to advance the President’s agenda in Congress. When the Senate is closely divided, for instance, the Vice President’s tiebreaking vote may be crucial for confirming the President’s nominees and passing laws that align with the President’s policies. Applying a criminal prohibition to the President’s conversations discussing such matters with the Vice President—even though they concern his role as President of the Senate—may well hinder the President’s ability to perform his constitutional functions.

It is ultimately the Government’s burden to rebut the presumption of immunity. We therefore remand to the District Court to assess in the first instance, with appropriate input from the parties, whether a prosecution involving Trump’s alleged attempts to influence the Vice President’s oversight of the certification proceeding in his capacity as President of the Senate would pose any dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.

This is the most important advantage of superseding the indictment. When someone boasted to Bloomberg that Jack Smith’s purported decision not to have a mini-trial on these issues was a “win” for Trump, they envisioned that this meant there would be no media friendly election-season developments, providing a way to get through (a successful or stolen) election so future President Trump could throw the case out.

Such a hearing would have been the best chance for voters to review evidence about Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 election result as he campaigns to regain the White House.

The decision is a win for Trump and his lawyers, who have fought efforts to reveal the substance of allegations against the former president.

The decision to supersede this indictment may have turned what could have been an immediate dispute about the viability of the indictment at all into an evidentiary dispute to be managed later. We’ll find out more on Tuesday.

At the very least, Jack Smith suggests he has something viable on which to arraign Trump (and Trump’s Xitter wails treating this as a real indictment suggest he may believe that).

Smith will still need to overcome the presumption created out of thin air by John Roberts on all of this. But he may do so from a posture where the utter absurdity of Roberts’ ruling are made obvious.

That’s one reason it’s important that Smith has included the tweet via which Trump almost got Mike Pence assassinated.

Smith rationalized doing so by emphasizing that Trump wrote it neither in the Oval Office nor with anyone’s assistance.

92. Beginning around 1:30 p.m., the Defendant, who had returned to the White

House after concluding his remarks, settled in the dining room off of the Oval Office. He spent much of the afternoon reviewing Twitter on his phone, while the television in the dining room showed live events at Capitol.

[snip]

94. At 2:24 p.m., the Defendant personally, without assistance, issued a Tweet intended to further delay and obstruct the certification: “Mike Pence didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done to protect our Country and our Constitution, giving States a chance to certify a corrected set of facts, not the fraudulent or inaccurate ones which they were asked to previously certify. USA demands the truth!” [my emphasis]

This situates this Tweet, which almost got Mike Pence killed, a private act for which Trump has no immunity. It may not work. But that’s the logic.

But the other changes in this passage are all about Fischer, about showing how Trump deliberately sicced a mob on the Capitol with the goal of making it impossible to count the certifications.

After adding language from Trump’s speech (included based on the justification that the rally was paid for by private funds) in which he emphasized the certification process, Smith added other language describing how Trump’s mob disrupted the vote certification over which Pence was presiding.

Everything italicized below is new.

86d. The Defendant specifically referenced the process by which electoral votes are counted during the proceeding, including by stating, “We have come to demand that Congress do the right thing and only count the electors who have been lawfully slated, lawfully slated.”

[snip]

90. On the floor of the House of Representatives, the Vice President, in his role as President of the Senate, began the certification proceeding. At approximately 1:11 p.m., the Vice President opened the certificates of vote and certificates of ascertainment that the legitimate electors for the state of Arizona had mailed to Washington, consistent with the ECA. After a Congressman and Senator lodged an objection to Arizona’s certificates, the House and Senate retired to their separate chambers to debate the objection.

91. A mass of people-including individuals who had traveled to Washington and to

the Capitol at the Defendant’s direction-broke through barriers cordoning off the Capitol grounds and advanced on the building, including by violently attacking law enforcement officers trying to secure it.

92. Beginning around 1:30 p.m., the Defendant, who had returned to the White

House after concluding his remarks, settled in the dining room off of the Oval Office. He spent much of the afternoon reviewing Twitter on his phone, while the television in the dining room showed live events at Capitol.

93. At 2:13 p.m., after more than an hour of steady, violent advancement, the

crowd at the Capitol broke into the building, and forced the Senate to recess. At approximately 2:20 p.m., the official proceeding having been interrupted, staffers evacuating from the Senate carried with them the legitimate electors’ certificates of vote and their governors’ certificates of ascertainment. The House also was forced to recess.

94. At 2:24 p.m., the Defendant personally, without assistance, issued a Tweet intended to further delay and obstruct the certification: “Mike Pence didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done to protect our Country and our Constitution, giving States a chance to certify a corrected set of facts, not the fraudulent or inaccurate ones which they were asked to previously certify. USA demands the truth!”

95. One minute later, at 2:25 p.m., the United States Secret Service was forced to evacuate the Vice President to a secure location.

96. At the Capitol, throughout the afternoon, members of the crowd chanted, “Hang Mike Pence!”; “Where is Pence? Bring him out!”; and “Traitor Pence!”

This narrative ties the mob, particularly the storming of the Senate chamber, directly to Trump’s goal of interrupting the counting of the electoral certificates. This instrumentality was always a part of the indictment — has been part of this investigation since no later than January 5, 2022. But Roberts’ dual interventions in the January 6 prosecutions forced Smith and crime scene prosecutors working under US Attorney Matthew Graves to make it far more explicit.

A significant number of mobsters either knew the import of the certificates ahead of time, and/or heard Trump describe the goal at the Ellipse, and when they stormed the Capitol, assaulted cops, and occupied the space that the Vice President had only just evacuated, they had the goal of preventing the authentic certificates from being counted.

And Jack Smith is making this argument before Judge Chutkan even as other prosecutors are making a parallel argument before other judges.

As DOJ laid out in their filing describing how they plan to retry Matt Loganbill (who joined Alex Jones as he opened a second, eastern front on the attack on the Capitol) under the new Fischer standard, Loganbill had the goal of getting Pence to shred the envelopes as early as December 20, 2020, and after he stormed the Capitol, he headed towards the Senate where he believed they were counting the vote.

- On December 20, 2020, the defendant wrote to Facebook, “This would take place Jan 6 Witnesses should be 60 feet away while Pence counts the Electoral College votes . . . Pence should open all the envelopes and then stack all the EC ballots in a pile, he should then shred all the envelopes and burn the shreds.” Gov. Ex. 302.47.

- On December 30, 2020, the defendant wrote to Facebook, “CALL SENATOR JOSH HAWLEY’S OFFICE T O D A Y AND LET HIM KNOW YOU SUPPORT HIS INTENT TO BE THE FIRST REPUBLICAN SENATOR TO CHALLENGE THE ELECTORAL VOTE ON JANUARY 6.” Gov. Ex. 302.49.

- On January 6, 2021, at 1:20 p.m., the defendant sent a text message, “Are you watching what’s going on in the house/ elector certification.” Gov. Ex. 303.

- On January 7, 2021, the defendant replies to a comment by another person on Facebook saying, “Why do you think we were trying every means possible to stop these idiots from stealing the presidency and destroying this nation.” Gov. Ex. 302.65

Evidence at trial showed Loganbill entered the Capitol, the location where the Electoral College ballots were located and where Congress and the Vice President were conducting the official proceeding.6 Gov Exs 101.1 and 701. Once inside, the defendant proceeded towards the Senate, where Congress would be handing objections to the Electoral College vote – attempting to obstruct Congress’ certification of the Electoral College ballots. The defendant knew where he was going. The government admitted a Facebook post by the defendant on January 7 and 8, 2021, he wrote, “They didn’t [let us in] at the chamber, we could have over run them, after 10-15 minutes of back and forth, we walked out” and “The only place [the police officers] wouldn’t give was the hallway towards the Rep. chamber.” Gov Exs 302.66 and 302.82, respectively. The “chamber” and “Rep. chamber” were where the Vice President and members of Congress would have been counting and certifying the Electoral College ballots. Gov Ex 701

[snip]

From this evidence, including the defendant’s express statement related to the destruction of the electoral ballots, the Court would be able to find, beyond a reasonable doubt, that the defendant acted to obstruct the certification of the electoral vote, and specifically, that he intended to, and attempted to, impair the integrity or availability of the votes (which are documents, records, or other things within the meaning of Fischer) under consideration by the Joint Session of Congress on January 6, 2021.

Of course, with any retrial, both parties would be permitted to introduce new evidence, or start the record over anew. Indeed, the government would likely introduce additional evidence related to the ballots and staffers attempts to remove the ballots from the chambers when the riot started.

6 According to the testimony of Captain Jessica Baboulis’ testimony, “[t]he official proceeding had suspended due to the presence of rioters on Capitol Grounds and inside the Capitol. ECF No. 31 at 23. As the Court said in its verdict, “It doesn’t matter to this count if he entered the building after the official proceeding had been suspended and Pence had been evacuated.” ECF No. 40 at 5. Loganbill attempted to and did obstruct the Electoral College vote, including the counting of ballots, the presence of members of Congress, and the presence of the Vice President.

Here’s how DOJ plans to prove that the Chilcoats, Shawndale and Donald, planned to prevent the votes from being counted by occupying the Senate.

[A]t approximately 2:46 p.m., the defendants watched rioters attempt to break open windows, then entered the Capitol building itself through a broken-open door on the building’s northwest side. A cell phone video shows that, after they learned of the breach, Donald Chilcoat cautioned Shawndale Chilcoat that they should let other rioters enter first. That way, if the police deployed pepper spray, those other rioters, and not the Chilcoats, would bear the brunt of it. In other words, the defendants knew they were not welcome, and they knew their entry might be met with force. After the defendants entered the building, they traveled to the Senate Chamber – the very place where the proceeding was taking place – and joined other rioters in occupying it. There, they took photographs and remained in the chamber while other rioters searched desks belonging to the former Vice President and to Senators.

Through their conduct, the defendants demonstrated an intent to invade and occupy the Capitol building and to stop the certification of the electoral college vote. And, critically, they were aware that this proceeding involved records, documents, or other things—specifically, the electoral votes that Congress was to consider. On January 4, 2021, via Facebook, a friend of Shawndale Chilcoat told her to “give Rob Portman a call and let him know what you think of him not rejecting the fraudulent votes.” Shawndale Chilcoat affirmed “just did.” Then, late on January 5 or early on January 6, Shawndale Chilcoat posted a message to Facebook saying that “[Vice President] Pence is stating he can not reject the votes.” On January 7, 2021, after the riot, Shawndale Chilcoat admitted “we were just trying to stop them from certifying the votes and didn’t know they were already gone.” On the same day, she also bragged, “[o]k so antifa is being blamed for breaking windows and storming congress. Um no, it was us I was with them and couldn’t be more proud.”

Here’s one of the most interesting things about yesterday’s superseding indictment.

The efforts to address Fischer are intertwined. While DOJ might be able to sustain some obstruction cases against rioters based on their own communications, and while Jack Smith might rescue this indictment with a focus on the effort to create fake elector certificates, Smith can only show that Trump almost got his Vice President assassinated if enough of the crime scene obstruction cases survive DC District review (and jury verdicts) such that Smith can show the mob was his instrument.

Jack Smith did things (describing that Trump was in his private Dining Room, not the Oval Office, noting that he sent the threatening Tweet with no assistance, labeling the rally a privately-funded speech, labeling Trump and Pence as candidates) that increase his chances of overcoming the presumption of immunity that John Roberts invented. But a number of judges (and some juries) are going to have to buy that a handful of members of the mob stormed the Capitol, and especially the Senate, with the intent of making it impossible to count vote for Joe Biden.

Here’s where things get interesting. As far as I’m aware, we have yet to see any of the superseding indictments for crime scene defendants against whom DOJ wants to sustain obstruction charges (we have seen superseding indictments against people against whom DOJ has replaced obstruction with something else, like rioting).

DOJ could have used a combined grand jury to do both, Trump and his mob. They’re each going to focus on the same issues: What staffers did to preserve the certificates as mobster came in, and the intent to prevent their counting.

They appear not to have done so; yesterday’s indictment lacks the date the grand jury was seated, which normal DC District grand juries have.

If that’s right, then Jack Smith (appears to have) seated a grand jury that could spend the next several months examining different charges, perhaps boosted by whatever precedents come out of the proceedings before Judge Chutkan and others, rather than simply sharing a grand jury with prosecutors doing much the same thing, addressing Fischer.

If Jack Smith succeeds in preserving this indictment — and that’s still a big *if* — then he will do so by making the argument that Trump, in his role as candidate, had the intention of using a mob to target the guy who played the ceremonial role of counting the vote. It would result in a collection of judicial holdings that presidential candidate Donald Trump had a mob target his Vice President in an attempt to remain President unlawfully.

Sure, John Roberts and his mob might yet try to overturn that. John Roberts might endorse the idea that presidential candidates, so long as they are the incumbent, can kill members of Congress to stay in power.

But doing so would clarify the absurdity of such a ruling.

Correction: Kyle Cheney reports that this is a grand jury seated last year. It has indicted other Jan6ers and so could do any 1512 indictments that require superseding.