Trump Spent $50 Million Paying Lawyers But Taxpayers Are Providing Loaner Laptops

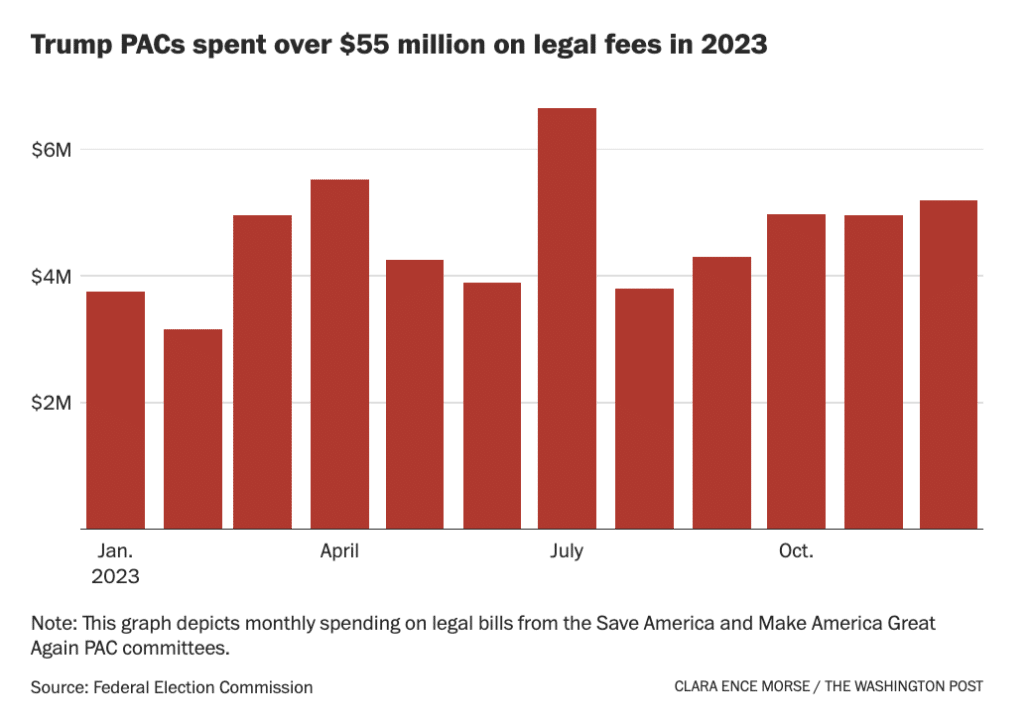

As multiple outlets reported this week, Trump spent over $50 million of the money raised from his supporters to pay for legal representation last year, both for himself and for those whose loyalty and silence he needs to ensure.

That includes upwards of $250,000 to a solicitor in London who filed a lawsuit against Christopher Steele that got dismissed this week.

Meanwhile, the response to Trump’s motion to compel in his stolen documents case reveals that, in October, Jack Smith provided two of the most important lawyers being paid by Trump funds, Carlos De Oliveira attorney, John Irving, and Walt Nauta attorney, Stan Woodward, loaner laptops.

Here’s how the response filing describes the loaners and the attorneys’ delay (and subsequent difficulties) accessing the surveillance footage in the proprietary media player Trump Organization uses.

In an email on October 24, 2023, months after the materials were made available to the defense, counsel for De Oliveira for the first time mentioned problems that he had encountered when attempting to access specific CCTV files that the Government had obtained from the Trump Organization and produced in discovery. The Government immediately arranged a call with counsel and technical personnel from the FBI to help resolve the reported issues. Exhibit E at 2- 3. During the call, counsel for De Oliveira explained that he did not own or have access to a laptop or desktop computer and was instead attempting to review the entirety of the Government’s discovery on a handheld tablet. Id. The Government then offered to lend him a laptop computer to facilitate his review. Id. Counsel for De Oliveira accepted the offer, and on November 1, 2023, the Government hand-delivered a computer to him. Since then, whenever De Oliveira’s counsel has raised technical issues with viewing specific Trump Organization CCTV files, the Government has promptly assisted with resolving these inquiries, providing tips and examples, and offering to set up calls as needed. See ECF No. 252 at 2 n.1.

Counsel for Nauta was copied on the October 24, 2023 email and reported “having the same issues” as counsel for De Oliveira. Exhibit E at 3. The Government extended the same laptop offer to Nauta’s counsel, who accepted the offer but noted that he planned to “return it promptly assuming I have the same issues.” Id. at 2. The Government also emailed defense counsel with additional suggestions to facilitate expedited review of CCTV footage, and counsel for Nauta responded within minutes, explaining that he planned to “run a test to extract data” to a separate drive, “and report back” about how it went. Id. at 1. The computer was delivered to Nauta’s counsel on November 1, and has not been returned. The Government heard nothing from Nauta’s counsel about CCTV for more than two months and thus reasonably believed that defense counsel had watched and was continuing to review the footage.

Then, on January 11, 2024, Nauta’s counsel confirmed that he was able to extract all of the files but had encountered difficulty attempting “to launch the [M]ilestone video application.” Exhibit F. Counsel’s reference to “Milestone” was to a proprietary media player and camera system vendor platform used by the Trump Organization to record, archive, and play video footage. In response, the Government worked with counsel to identify his misstep in attempting to launch the player and provided detailed instructions and screenshots about how to do so. Exhibit G. This most recent problem—the apparent basis for the statement in defendants’ brief that “[d]efense counsel for Mr. Nauta was not able to launch the proprietary video player at all” (ECF No. 262 at 61)—omits that for over two months he did not even attempt to launch the player the Government provided (on the laptop that the Government also provided), and did not do so until days before the motion to compel was due. In any event, once notified of the problem, the Government provided prompt assistance in diagnosing the simple and easily correctable user error that has now been resolved. [my emphasis]

The filing is worth reading for more than the revelation that John Irving doesn’t own a laptop.

It starts with a 15-page section describing the course of the investigation.

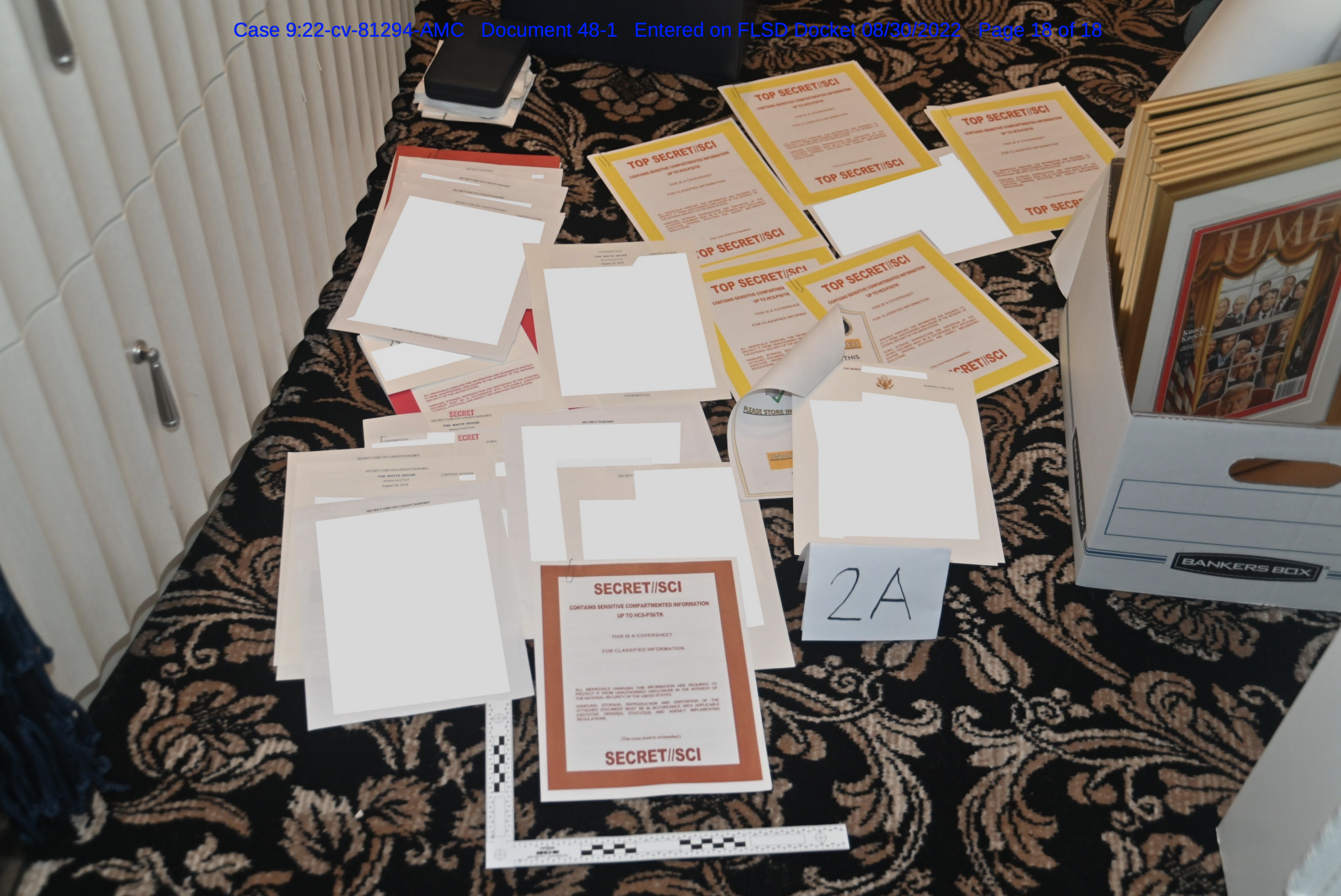

As Politico first reported, it describes how upwards of 45,000 people entered Mar-a-Lago during the period when Trump was hoarding the nation’s nuclear secrets without getting their names checked by Secret Service.

of the approximately 48,000 guests who visited Mar-a-Lago between January 2021 and May 2022, while classified documents were at the property, only 2,200 had their names checked and only 2,900 passed through magnetometers;

And it provides details of Trump’s lack of security clearance and his loss of Q Clearance after he got fired by voters.

The defendants next request evidence related to the “attempt to retroactively terminate President Trump’s security clearance and related disclosures.” ECF No. 262 at 38-42. This request includes any information concerning “President Trump’s security clearances, read-ins, and related training,” as well as, “where applicable, the failure to maintain formal documentation and training that is typically required.” ECF No. 262 at 40-41. The defendants specifically assert (ECF No. 262 at 41) that the Government must search the Scattered Castles database (a database of security clearances maintained by the Intelligence Community) and a similar database maintained by the Department of Defense (the Defense Information System for Security, which replaced the Joint Personnel Adjudication System). The Government has produced the results of a search in Scattered Castles, which yielded no past or present security clearances for Trump.

[snip]

First, the Government has already produced all non-privileged, responsive materials. The Government produced to the defendants through discovery a memorandum authored by an assistant general counsel in DOE, dated June 28, 2023. Exhibit 59. The memorandum stated that DOE had granted a Q clearance to Trump on February 9, 2017, “in connection with his current duties” as President, see id., pursuant to a statutory provision that permits DOE to grant clearances without a background check if doing so is in the national interest, see 42 U.S.C. § 2165(b).25 The memorandum further stated that when DOE officials learned that Trump remained listed in DOE databases (its Central Personnel Clearance Index and Clearance Action Tracking System) as possessing a Q clearance after his term ended, they determined that Trump’s clearance had terminated upon the end of his presidency and that the DOE databases should be updated to reflect that termination. Exhibit 59. In response to the defendants’ motion, the Government made a second request for documents to DOE on January 24, 2024, and included the categories of information in Trump’s request described above. The Government is now producing approximately 30 pages of responsive materials, while withholding eight emails under the deliberative-process privilege.

24 The document charged in Count 19 may be viewed by someone holding an active and valid Q clearance. Trump’s Q clearance ended when his term in office ended, even though the database was only belatedly updated to reflect that reality. But even if Trump’s Q clearance had remained active, that fact would not give him the right to take any documents containing information subject to the clearance to his home and store it in his basement or anywhere else at Mar-a-Lago. No Q clearance holder has authorization to remove documents from a proper place of storage and keep them for himself. And a Q clearance would not even permit access to, much less offsite possession of, the documents charged in Counts 1-18 and 20-32.

25 The authority to classify and control access to national defense information rests with the President, see Dep’t of Navy v. Egan, 484 U.S. 518, 527 (1988), and accordingly, during their terms in office, Presidents are not required to obtain security clearances before accessing classified information, see 50 U.S.C. § 3163 (“Except as otherwise specifically provided, the provisions of this subchapter [dealing with access to classified information] shall not apply to the President and Vice President, Members of the Congress, Justices of the Supreme Court, and Federal judges appointed by the President.”). Those exceptions for the President and other high-ranking officials apply only during their terms of office. See, e.g., Executive Order 13526, § 4.4(a) (authorizing access to classified information by former officials, including former Presidents, only under limited and enumerated circumstances). [my emphasis]

These details should, but won’t, resolve all sorts of confusion about under what authority Presidents and Vice Presidents access classified information.