John Durham Wails about Michael Sussmann Adopting His Own Evidentiary Standards

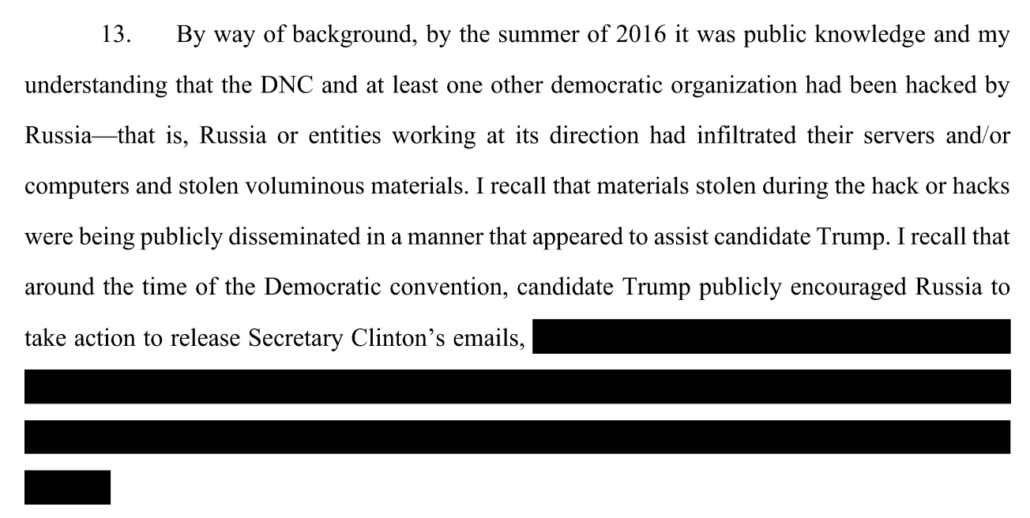

Last month, I noted that John Durham had forgotten to file a motion in limine to exclude evidence of the rampant hacking Russia did against Hillary Clinton in 2016.

But along the way, Durham’s tunnel vision about 2016 led him to forget to exclude the things that do go to Sussmann’s state of mind, such as the very real Russian attack on Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump’s public call for more such attacks.

So while Durham may be excluded from claiming that a private citizen’s attempt to learn about real crimes by a Presidential candidate before he is elected amounts to a criminal conspiracy, it is too late for Durham now to try to exclude evidence about Sussmann’s understanding of Donald Trump’s very real role in a hack of his client.

In a challenge to Michael Sussmann’s trial exhibits last night, Durham has effectively tried to belatedly correct that error.

Meanwhile, in Sussmann’s own challenge to Durham’s exhibits, he labels 121 exhibits as hearsay, 267 as irrelevant, and 143 as prejudicial.

Durham objects to three kinds of evidence, all utterly pertinent to Sussmann’s defense, and all akin to the same kind of evidence Durham has fought to introduce to substantiate a conspiracy theory Durham admits he doesn’t have evidence to prove.

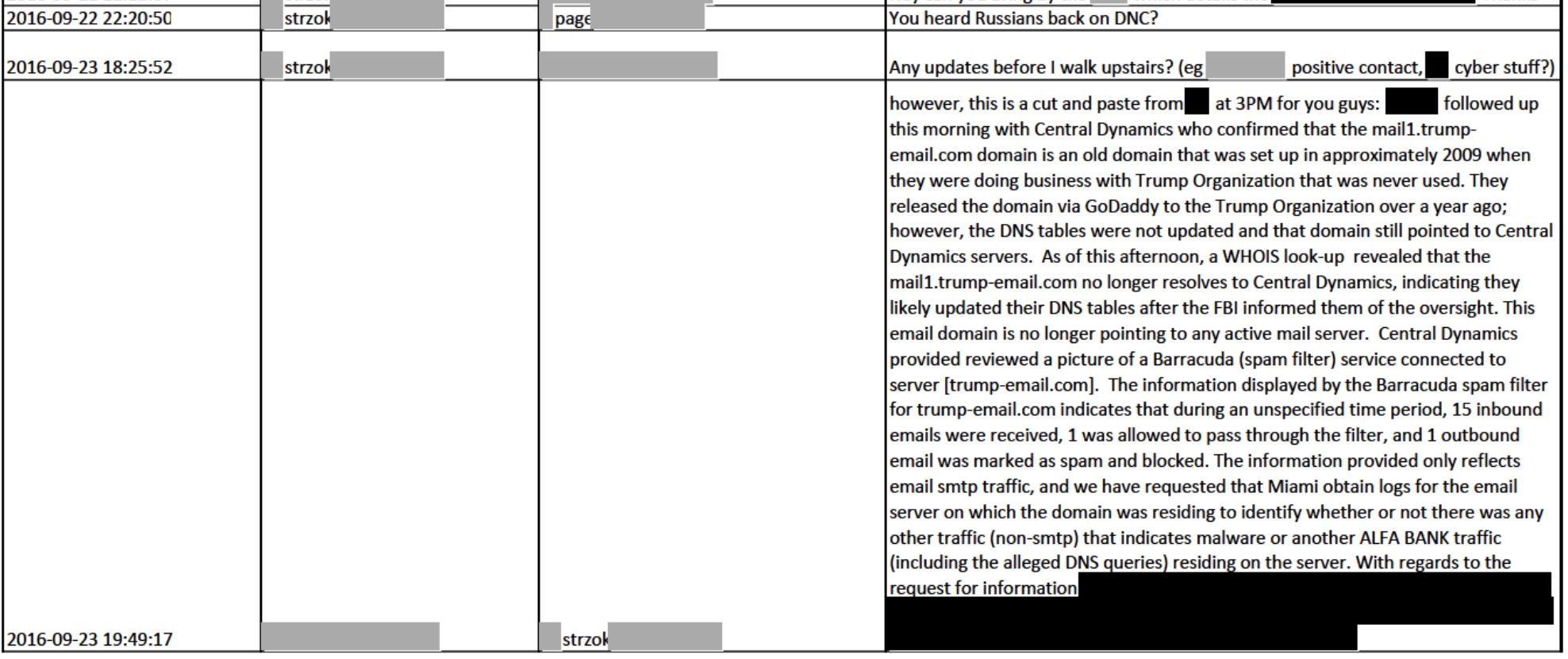

The first are hundreds of emails Sussmann had with the FBI pertaining to hacks of the DNC and Hillary (Durham describes hacking attempts against Hillary as “cybersecurity issues” as if unsuccessful hacks don’t count as hacks).

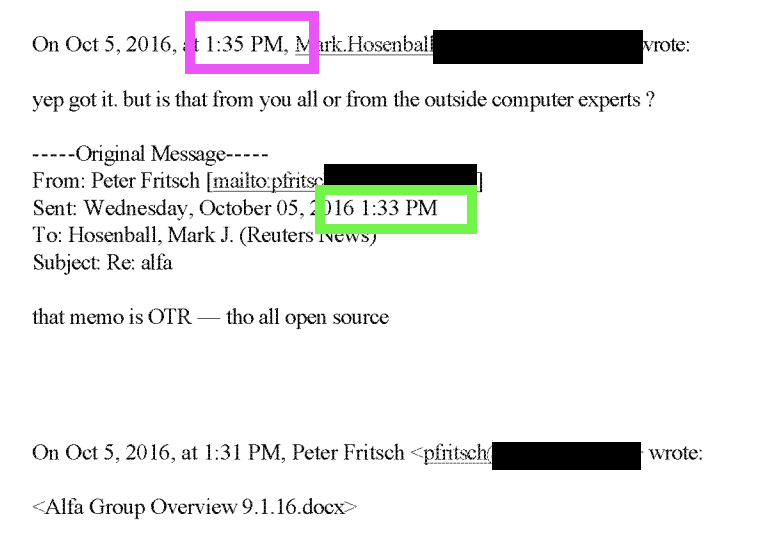

Durham claims that these should come in primarily to disprove Durham’s assumptions about Sussmann’s billing entries, not to illustrate how reasonable it was to be concerned about a DNS anomaly involving Trump and a Russian bank. Durham — who asked to include a voir dire question assuming as fact that the Hillary campaign “promot[ed …] the Trump/Russia collusion narrative” — doesn’t want the FBI’s investigation of serial hacks targeting Democrats to come in to support the fact that such hacks occurred. And he wants to exclude the sheer volume, arguing (not unfairly) that would be cumulative, but not acknowledging that the volume does speak to Sussmann’s focus during a period when Durham claims Sussmann was instead feverishly conspiring to attack Trump. Finally, Durham claims that Sussmann’s focus on Russian cyberattacks is totally unrelated to his concern about an anomaly seeming to suggest a tie between Trump and Alfa.

First, the defendant’s Exhibit List includes more than approximately 300 email chains between and among the defendant and various FBI personnel reflecting the defendant’s work relating to (i) the hack of the Democratic National Committee (“DNC”), and (ii) cybersecurity issues pertaining to the Hillary for America Campaign (“HFA”). As an initial matter, the Government is not contesting that the defendant worked for both of those entities on cybersecurity issues. The Government also acknowledges that certain emails reflecting the defendant’s work on behalf of HFA on cybersecurity matters are potentially relevant and admissible insofar as the defendant might use those emails to argue that some or all of the billing entries to HFA that the Indictment alleges related to the Russian Bank-1 allegations were, in fact, related to work on other matters for HFA. The Government respectfully submits however, that the Court should carefully analyze each email that the defendant offers at trial to ensure that it is not admitted for its truth but instead is offered for a permissible purpose, such as to prove the defendant’s state of mind or the email’s effect on one or more of its recipients. Fed. R. Evid. 801(c); United States v. Safavian, 435 F. Supp. 2d 36, 45–46 (D.D.C. 2006). In addition, the defendant should not be permitted to offer dozens of emails to establish such basic facts because such voluminous evidence would be cumulative and unduly prejudicial. Fed. R. Evid. 403 (permitting courts to preclude parties from “needlessly presenting cumulative evidence”).

As to the dozens of communications regarding the defendant’s work regarding the DNC hack, these emails are largely irrelevant. The defendant billed his work on that matter to the DNC, not HFA. The Indictment alleges specifically that the defendant billed time on the Russian Bank1 allegations to HFA. These emails therefore do not support any inferences or arguments relating to the defendant’s alleged billed time for the Russian Bank-1 allegations. Instead, they contain extensive detail on collateral issues. See, e.g., Defense Ex. 306 (Email dated September 14, 2016 from FBI Special Agent E. Adrian Hawkins to Michael Sussmann, et al., stating in part, “We just got notified by some industry personnel that some previously unreleased DNC documents were uploaded to Virus Total today. In the files there was a contact list that I attached here with lots of personal emails for people. Rumor is that these files are supposed to be the network share for a guy named [named redacted] who worked IT until April 2011.”)

To the extent the defendant is offering such emails in support of arguments that (i) the defendant was an accomplished cybersecurity lawyer, (ii) the defendant was known and respected at the FBI, or (iii) the defendant was concerned about, and involved in responding to, cyberattacks carried out by the Russian Federation, such arguments are peripheral to the charged offense because they do not concern the Russian Bank-1 allegations or the defendant’s statements to the FBI about those allegations. The defendant’s potential arguments in this regard support, at best, the admission of a limited quantity of these emails to establish basic facts about the defendant’s representation of the DNC. Admitting all or most of these exhibits, however, would be highly cumulative and would waste the jury’s time with highly-detailed evidence concerning a tangential matter (the DNC hack) that is not at issue in this trial. Accordingly, the Government respectfully submits that the Court should admit only a limited number of these emails that are not being offered for their truth. [my emphasis]

It is, of course, rank nonsense to claim that the ongoing hacks targeting Democrats were unrelated to efforts to chase down a DNS anomaly. But Durham’s entire team either claims or genuinely does not understand the connection.

Then, in addition to attempting to exclude the notes of an FBI Agent who investigated the Alfa Bank allegations, Durham wants to exclude notes showing that the word “client” came up at a March 6, 2017 briefing on all the Russian allegations for Dana Boente.

The defense also may seek to offer (i) multiple pages of handwritten notes taken by an FBI Headquarters Special Agent concerning his work on the investigation of the Russian Bank-1 allegations, (including notes reflecting information he received from the FBI Chicago case team), and (ii) notes taken by multiple DOJ personnel at a March 6, 2017 briefing by the FBI for the then-Acting Attorney General on various Trump-related investigations, including the Russian Bank-1 allegations. See, e.g., Defense Ex. 353, 370, 410. The notes of two DOJ participants at the March 6, 2017 meeting reflect the use of the word “client” in connection with the Russian Bank-1 allegations. The defendant did not include reference to any of these notes – which were taken nearly six months after the defendant’s alleged false statement – in its motions in limine. Moreover, the DOJ personnel who took the notes that the defendant may seek to offer were not present for the defendant’s 2016 meeting with the FBI General Counsel. And while the FBI General Counsel was present for the March 6, 2017 meeting, the Government has not located any notes that he took there.

I mean, Durham is not wrong on the evidentiary issue: these notes far post-date Sussmann’s alleged lie (though, ironically, the Jeffrey Jensen team added a date to and relied on what must be one set of these notes in their efforts to blow up the Mike Flynn prosecution). While they may reflect James Baker’s statements reflecting knowledge that Sussmann had a client, they’re hearsay.

But Durham is doing both those same things, presenting hearsay notes to substantiate Baker’s knowledge and claiming that meetings that long post-date Sussmann’s alleged lie may be indicative of what Sussmann and Baker actually said in September 2016. Durham has no grounds to complain about such evidentiary sloppiness, because that’s what his entire case consists of.

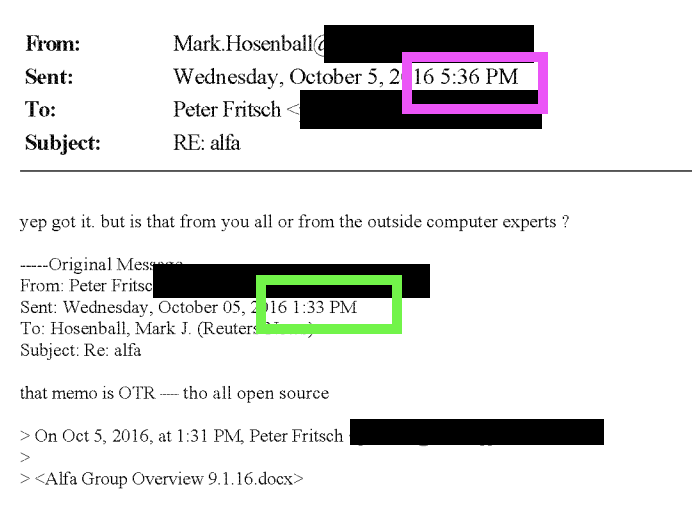

Finally, Durham — who started his speaking indictment by focusing on two news articles and not only considers Fusion’s communications with the press to be key evidence in his conspiracy theory but even insinuates that everything certain reporters were doing must have come from the Democrats — complains that Sussmann wants to introduce a slew of newspaper articles from 2016. He’s worried that it’ll elicit a sense of horror among the jury.

The Government will not dispute that the DNC was a victim of the aforementioned hack, nor will it dispute that the defendant carried out significant legal work in relation to the hack. The Government similarly will not seek to prove one way or the other whether Donald Trump maintained ties – illicit, unlawful, or otherwise – to Russia, other than to establish facts relating to the FBI’s investigation of the Russian Bank-1 allegations. Permitting the defense to admit the above-listed series of news articles would amount to the ultimate “mini-trial” – of the very sort that will distract and confuse the jury without offering probative evidence. United States v. Ring, 706 F.3d 460, 472 (D.C.Cir.2013) (“Unfair prejudice within its context means an undue tendency to suggest [making a] decision on an improper basis, commonly, though not necessarily, an emotional one.”); see also Carter v. Hewitt, 617 F.2d 961, 972 (3d Cir.1980) (explaining that evidence is unfairly prejudicial “if it appeals to the jury’s sympathies, arouses its sense of horror, provokes its instinct to punish, or otherwise may cause a jury to base its decision on something other than the established propositions in the case.”) (citations omitted). Accordingly, this Court should exclude the above-referenced news articles.

This is the argument that, I noted in real time, Durham should have made last month.

But Durham is also not accounting for how central the articles cited are to Sussmann’s ability to rebut the conspiracy theory Durham wants to tell. The articles show that:

- Trump’s coziness with Russia, one reason cited in Marc Elias’ declaration for hiring Fusion, was broadly perceived as unusual

- Trump’s undisclosed financial ties with Russia were a general and persistent concern

- Public reporting had confirmed the Russian attribution of the DNC hack before Trump asked Russia to hack Hillary some more and the press widely viewed Trump’s “Russia are you listening” comment as a request for more hacks

- The reporters or outlets Durham wants to make an issue were doing their own reporting on Trump’s Russian ties were doing reporting not seeded by Fusion

- The corruption scandal implicating Paul Manafort led to his ouster from the campaign during the period researchers were working on the anomaly

Durham complains that “many of [the articles] far predate the defendant’s meeting with the FBI General Counsel,” but only one predates the data collection that Durham has made the central focus of his case and another — Ellen Nakashima’s article reporting the DNC hack — directly kicked off that data collection effort.

These articles explain why it was reasonable, not just for the Democrats’ cybersecurity lawyer who was spending most of his days trying to fight back against a persistent Russian hack, but also for the researchers and Rodney Joffe to try to first look for more Russian hacking (including that victimizing Republicans), and when they found an anomaly, to try to chase it down and even to bring it to the FBI for further investigation. Several threads of these articles — pertaining to Trump’s request that Russia hack Hillary and to Manafort’s corruption — were explicitly invoked in discussions that Durham wants to claim must arise from political malice.

Indeed, as a whole, these articles provide far more reasonable explanations for actions that Durham has claimed, as fact, could only arise out of political malice.

Some of Durham’s complaints are reasonable from an evidentiary standard. But they’re utterly ridiculous given his own wild conspiracy theorizing. And many of these exhibits are utterly necessary to rebut the more outlandish things Durham has been claiming for months.