Yes, in Gartenlaub, FBI Was Hunting for Child Porn in the Name of Foreign Intelligence Information

Over at Motherboard, I’ve got a piece on the Keith Gartenlaub hearing in the Ninth Circuit on December 4. Gartenlaub was appealing his conviction for possession of child porn, in part, based on the argument that the government shouldn’t have been able to look for child porn under the guise of searching for foreign intelligence information.

As I note, the public hearing seems to have gone reasonably well for Gartenlaub, with a close focus on how the US v Comprehensive Drug Testing precedent in the 9th Circuit, which requires searches of digital media to be appropriate to the purpose of the search, might limit searches for Foreign Intelligence Information.

Anthony Lewis, arguing for the government, suggested that FISA was different from the Rule 41 context; in FISA, he argued, specificity would be handled by post collection minimization procedures.

Anthony Lewis, arguing for the government, responded to Gartenlaub’s argument with vague promises that the minimization procedures—rules that FISA imposes on data obtained under the statute—would take care of any Fourth Amendment concerns. “The minimization procedures themselves really supply the answer in the FISA context,” Lewis said. Accessing data found during a search “simply operates differently in the FISA context, in which there is a robust set of procedures that exist on the back end of the search through acquisition, retention, and dissemination that is simply unlike what happens in a Rule 41 context.”

Lewis argued (and this is not in the post) that because FISA permits the sharing of criminal information, minimization procedures would always using evidence of a crime found in a search.

If it is evidence of a crime, then the minimization procedures — the statute does not call for it to be minimized. There are other procedures in place, some of which I can’t discuss in this open proceeding, but there are procedures in place that limit the use of that. Some of them are in the statute itself that Attorney General approval is required in order to use information obtained or derived from FISA.

The judges didn’t seem convinced. Each judge on the panel voiced a theory by which they could rule for Gartenlaub (which is different from giving him any kind of relief).

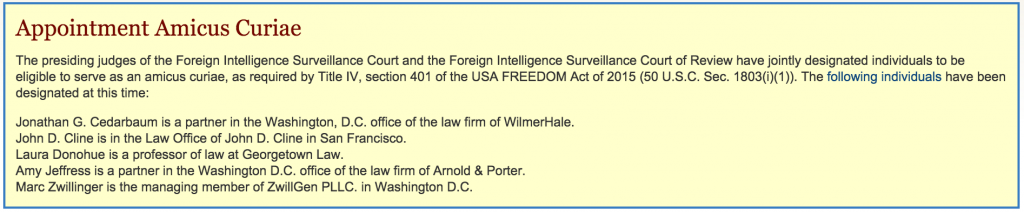

Judge Ronald Gould worried that if the government found evidence that wasn’t foreign intelligence but revealed something urgent—he used the example of a serial killer’s next targets throughout the hearing—it would need a way to use that information. Gartenlaub’s attorney John Cline and amicus lawyer Ashley Gorski, arguing for the ACLU, both noted an exigent circumstance exception could justify the use of the information on the hypothetical serial killer.

Judge Lawrence Piersol, a senior district court judge from Idaho, seemed to imagine district court judges providing individualized review on whether the information was reasonably obtained in a FISA-authorized search, possibly with the involvement of the court’s own cleared experts.

Judge Kim Wardlaw, who sat on the en banc panel for the Ninth Circuit precedent in question, asked why, when the government saw “a whole database [that] obviously suggests child porn” it couldn’t “go get another warrant?” So she seemed to favor a system where the government would have to get a criminal warrant to obtain child porn. That would present very interesting questions in this case, however, since the government obtained a criminal warrant based on probable cause that Gartenlaub was sharing information on Boeing intellectual property with China before it executed the FISA-authorized search that discovered the child porn.

But (also not in the post) Piersol added another example — one that has direct relevance for the most prominent investigation in the country implicating FISA, the Mueller investigation, which indicted FISA target Paul Manafort for what amounts to money laundering.

What about instead if you’re going through and looking for foreign intelligence information and you find a tremendous number of financial transactions which looks like it could well be money laundering. What do you do with that? Nothing? I mean, you just go ahead and prosecute it? You don’t have to worry about the fact that you weren’t looking for that?

Sure, Manafort’s not in the Ninth, but the judges sure seem inclined to limit the government’s ability to use a FISA order to troll through digital devices to find evidence of a crime that they can then use — as they did with Gartenlaub and are trying to do with Manafort — to coerce cooperation from the defendant. Depending on how they framed such a limit, it might seriously limit how the government enacted other FISA authorities in the circuit (which of course includes Silicon Valley — though any secondary searches would take place in Maryland or some other NSA facility); of very particular import, it would affect how the government implements its 2014 exception, whereby the NSA collects location obscured data (including entirely domestic communications) but then purges all but that which can be retained, including for criminal purposes, after the fact.

Which is why it’s so troubling that — as has happened in the last case where a defendant had a good argument to look at his FISA materials — the panel asked Lewis to stick around for an ex parte session.

Things were going swimmingly, that is, up until Wardlaw’s last comments to the government’s lawyer, Lewis. As he finished, she said she had no further questions, but added, “We’re going to ask you to stay after the hearing, to be available for us.” Lewis responded, “Understood, your honor,” as if he (and the people whose bags were sitting behind his counsel’s table but who were not themselves present) had advance warning of this. “Understood,” Lewis repeated again.

That was the first Gartenlaub’s team learned of the secret meeting the panel of judges had planned.

So after having presented a lackluster argument, Lewis was going to get a chance, it appears, to argue his case without Gartenlaub’s lawyers present, to be able to argue that not even Ninth Circuit precedent can limit the government’s authority to search with no limits in the name of national security.

There’s apparently precedent for this. Cline, who worked on the appeal of a defendant who almostgot FISA review, Adel Daoud, said the appeals court judges booted him and the other defense lawyers out of the courtroom for a similar ex parte hearing in that case too.

“The Seventh Circuit cleared the courtroom after the public argument and then allowed only government attorneys back in for the classified, ex parte session,” he said.

The session would not only give Lewis a chance to make further argument that the law envisions finding criminal evidence and using it to flip targets, but also to explain why, if the panel ruled in the direction it appeared they might, it would cause problems with other NSA collection.

Here’s the thing though — and the reason why an ex parte proceeding is so problematic here.

If given the chance, Gartenlaub would be able to argue in fairly compelling manner that the government set out to find things like child porn. That’s because one of the first steps of a forensics search — according to Gartenlaub’s forensics expert, Jeff Fischbach, who attended the hearing — is to set what you’re looking for. There’s a button to exclude all images and videos; by turning it off you vastly accelerate the search. And in Gartenlaub’s case, the government claimed to be looking for very specific kinds of foreign intelligence information: Boeing intellectual property, or any materials suggesting that Gartenlaub was dealing in same. The IP would have been CAD drawings stolen in digital form, not images. So to search what the government claimed it wanted to search for, there would have been no reason to search through any videos or photos. Which would have excluded finding the decade old child porn lying unopened on the hard drive.

As Wardlaw (who had been on the CDT panel) laid out,

The main problem we had was that in CDT, the government was authorized to look at the files pertaining to certain individuals — I believe Barry Bonds — and instead, they went further, and looked at the drug testing files for other baseball players. So that search was not authorized. They were not the subjects of the warrant and the warrant was circumscribed that way. Here, the warrant is any foreign intelligence data, it’s not narrower than that.

We don’t actually know (and it’s likely Wardlaw doesn’t either, at this point). But the government claimed to be searching for very specific things, tied to very specific claims of stolen IP from Boeing. Yet they necessarily designed their search to find far more than that. Which is how they found no foreign intelligence, but instead unopened child porn.