David Barron’s ECPA Memo

Last week, I laid out the amazing coinkydink that DOJ provided Sprint a bunch of FISA opinions — including the December 12, 2008 Reggie Walton opinion finding that the phone dragnet did not violate ECPA — on the same day, January 8, 2010, that OLC issued a memo finding that providers could voluntarily turn over phone records in some circumstances without violating ECPA.

Looking more closely at what we know about the opinion, I’m increasingly convinced it was not a coinkydink at all. I suspect that the memo not only addresses FBI’s exigent letter program, but also the non-Section 215 phone dragnet.

As a reminder, we first learned of this memo when, in January 2010, DOJ’s Inspector General issued a report on FBI’s practice of getting phone records from telecom provider employees cohabiting at FBI with little or no legal service. The report was fairly unique in that it was released in 3 versions: the public unclassified but heavily redacted version, a Secret version, and a Top Secret/SCI version. Given how closely parallel the onsite telecom provider program was with the phone dragnet, that always hinted the report may have touched on other issues.

Roughly a year after the IG Report came out, EFF FOIAed the memo (see page 30). Over the course of the FOIA litigation — the DC Circuit rejected their appeal for the memo in January — DOJ provided further detail about the memo.

Here’s how OLC Special Counsel Paul Colborn described the memo (starting at 25):

The document at issue in this case is a January 8, 2010 Memorandum for Valerie Caproni, General Counsel of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (the “FBI”), from David J. Barron, Acting Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel (the “Opinion”). The OLC Opinion was prepared in response to a November 27, 2009 opinion request from the FBI’s General Counsel and a supplemental request from Ms. Caproni dated December 11, 2009. These two requests were made in order to obtain OLC advice that would assist FBI’s evaluation of how it should respond to a draft Report by the Office of Inspector General at the Department of Justice (the “OIG”) in the course of a review by the OIG of the FBI’s use of certain investigatory procedures.In the context of preparing the Opinion, OLC, as is common, also sought and obtained the views of other interested agencies and components of the Department. OIG was aware that the FBI was seeking legal advice on the question from OLC, but it did not submit its views on the question.

The factual information contained in the FBI’s requests to OLC for legal advice concerned certain sensitive techniques used in the context of national security and law enforcement investigations — in particular, significant information about intelligence activities, sources, and methodology.

Later in his declaration, Colborn makes it clear the memo addressed not just FBI, but also other agencies.

The Opinion was requested by the FBI and reflects confidential communications to OLC from the FBI and other agencies. In providing the Opinion, OLC was serving an advisory role as legal counsel to the Executive Branch. In the context of the FBI’s evaluation of its procedures, the general counsel at the FBI sought OLC advice regarding the proper interpretation of the law with respect to information-gathering procedures employed by the FBI and other Executive Branch agencies. Having been requested to provide counsel on the law, OLC stood in a special relationship of trust with the FBI and other affected agencies.

And FBI Record/Information Dissemination Section Chief David Hardy’s declaration revealed that an Other Government Agency relied on the memo too. (starting at 46)

This information was not examined in isolation. Instead, each piece of information contained in the FBI’s letters of November 27, 2009 and December 11, 2009, and OLC’s memorandum of January 8, 2010, was evaluated with careful consideration given to the impact that disclosure of this information will have on other sensitive information contained elsewhere in the United States intelligence community’s files, including the secrecy of that other information.

[snip]

As part of its classification review of the OLC Memorandum, the FBI identified potential equities and interests of other government agencies (“OGAs”) with regard to the OLC memo. … FBI referred the OLC Memo for consultation with those OGAs. One OGA, which has requested non-attribution, affirmatively responded to our consultation and concurs in all of the classification markings.

Perhaps most remarkably, the government’s response to EFF’s appeal even seems to suggest that what we’ve always referred to as the Exigent Letters IG Report is not the Exigent Letters IG Report!

Comparing EFF’s claims (see pages 11-12) with the government’s response to those claims (see pages 17-18), the government appears to deny the following:

- The Exigent Letters IG Report was the 3rd report in response to reporting requirements of the USA PATRIOT reauthorization

- FBI responded to a draft of the IG Report by asserting a new legal theory defending the way it had obtained certain phone records in national security investigations, which resulted in the January 8, 2010 memo

- The report didn’t describe the exception to the statute involved and IG Glenn Fine didn’t recommend referring the memo to Congress

- In response to a Marisa Taylor FOIA, FBI indicated that USC 2511(2)(f) was the exception relied on by the FBI to say it didn’t need legal process to obtain voluntary disclosure of phone records

Along with these denials, the government reminded that the report “contained significant redactions to protect classified information and other sensitive information.” And with each denial (or non-response to EFF’s characterizations) it “respectfully refer[red] the Court to the January 2010 OIG report itself.”

The Exigent Letters IG Report is not what it seems, apparently.

With all that in mind, consider two more details. First, as David Kris (who was the Assistant Attorney General during this period) made clear in his paper on the phone (and Internet) dragnet, in addition to Section 215, the government obtained phone records from the telecoms under USC 2511(2)(f), the clause in question.

And look at how the chronology maps.

November 5, 2008: OLC releases opinion ruling sneak peak and hot number requests (among other things) impermissible under NSLs

December 12, 2008: Reggie Walton rules that the phone dragnet does not violate ECPA

Throughout 2009: DOJ confesses to multiple violations of Section 215 program, including:

- An alert function that serves the same purpose as sneak peaks and also violates Section 215 minimization requirements

- NSA treated Section 215 derived data with same procedures as EO 12333 data; that EO 12333 data included significant US person data

- One provider’s (which I originally thought was Sprint, then believed was Verizon, but could still be Sprint) production got shut down because it included foreign-to-foreign data (the kind that, according to the OLC, could be obtained under USC 2511(2)(f)

Summer and Fall, 2009: Sprint meets with government to learn how Section 215 can be used to require delivery of “all” customer records

July 9, 2009: Sprint raises legal issues regarding the order it was under; Walton halts production from provider which had included foreign-to-foreign production

October 30, 2009: Still unreleased primary order BR 09-15

November 27, 2009: Valerie Caproni makes first request for opinion

December 11, 2009: Caproni supplements her request for a memo

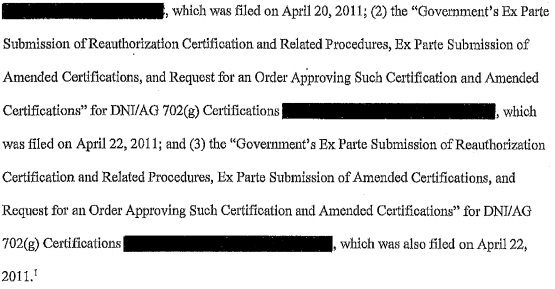

December 16, 2009: Application and approval of BR 09-19

December 30, 2009: Sprint served with secondary order

January 7, 2010: Motion to unseal records

January 8, 2010: FISC declassifies earlier opinions; DOJ and Sprint jointly move to extend time when Sprint can challenge order; and OLC releases OLC opinion; FISC grants motion (John Bates approves all these motions)

January 11, 2010: DOJ moves (in a motion dated January 8) to amend secondary order to incorporate language on legality; this request is granted the following day (though we don’t get that order)

January 20, 2010: IG Report released, making existence of OLC memo public

This memo is looking less and less like a coinkydink after all, and more and more a legal justification for the provision of foreign-to-foreign records to accompany the Section 215 provision. And while FBI said it wasn’t going to rely on the memo, it’s not clear whether NSA said the same.

Golly. It’d sure be nice if we got to see that memo before David Barron got to be a lifetime appointed judge.