Chris Wray’s DodgeBall and Trump’s Latest Threats

Though I lived-tweeted it, I never wrote up Christopher Wray’s confirmation hearing to become FBI Director. Given the implicit and explicit threats against prosecutorial independence Trump made in this interview, the Senate should hold off on Wray’s confirmation until it gets far more explicit answers to some key questions.

Trump assails judicial independence

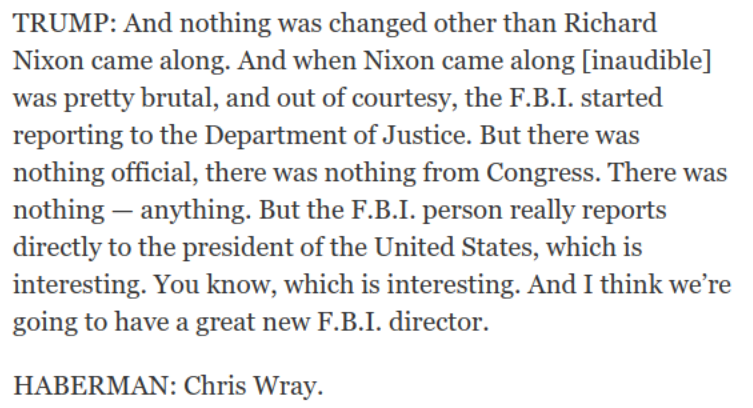

The NYT interview is full of Trump’s attacks on prosecutorial independence.

It started when Trump suggested (perhaps at the prompting of Michael Schmidt) that Comey only briefed Trump on the Christopher Steele dossier so he could gain leverage over the President.

Later, Trump called Sessions’ recusal “unfair” to the President.

He then attacked Rod Rosenstein by suggesting the Deputy Attorney General (who, Ryan Reilly pointed out, is from Bethesda) must be a Democrat because he’s from Baltimore.

Note NYT goes off the record (note the dashed line) with Trump in his discussions about Rosenstein at least twice (including for his response to whether it was Sessions’ fault or Rosenstein’s that Mueller got appointed), and NYT’s reporters seemingly don’t think to point out to the President that he appeared to suggest he had no involvement in picking DOJ’s #2, which would seem to be crazy news if true.

Finally, Trump suggested (as he has elsewhere) Acting FBI Director Andrew McCabe is pro-Clinton.

Having attacked all the people who are currently or who have led the investigation into him (elsewhere in the interview, though, Trump claims he’s not under investigation), Trump then suggested that FBI Directors report directly to the President. In that context, he mentioned there’ll soon be a new FBI Director.

In other words, this mostly softball interview (though Peter Baker made repeated efforts to get Trump to explain the emails setting up the June 9, 2016 meeting) served as a largely unfettered opportunity for Trump to take aim at every major DOJ official and at the concept of all prosecutorial independence. And in that same interview, he intimated that the reporting requirements with Christopher Wray — who got nominated, ostensibly, because Comey usurped the chain of command requiring him to report to Loretta Lynch — would amount to Wray reporting directly to Trump.

Rosenstein does what he says Comey should be fired for

Close to the same time this interview was being released, Fox News released an “exclusive” interview with Rod Rosenstein, one of two guys who acceded to the firing of Jim Comey ostensibly because the FBI Director made inappropriate comments about an investigation. In it, the guy overseeing Mueller’s investigation into (in part) whether Trump’s firing of Comey amounted to obstruction of justice, Rosenstein suggested Comey acted improperly in releasing the memos that led to Mueller’s appointment.

And he had tough words when asked about Comey’s recent admission that he used a friend at Columbia University to get a memo he penned on a discussion with Trump leaked to The New York Times.

“As a general proposition, you have to understand the Department of Justice. We take confidentiality seriously, so when we have memoranda about our ongoing matters, we have an obligation to keep that confidential,” Rosenstein said.

Asked if he would prohibit releasing memos on a discussion with the president, he said, “As a general position, I think it is quite clear. It’s what we were taught, all of us as prosecutors and agents.”

While Rosenstein went on to defend his appointment of Mueller (and DOJ’s reinstatement of asset forfeitures), he appears to have no clue that he undermined his act even as he defended it.

Christopher Wray’s dodge ball

Which brings me to Wray’s confirmation hearing.

In fact, there were some bright spots in Christopher Wray’s confirmation hearing, mostly in its last dregs. For example, Dick Durbin noted that DOJ used to investigate white collar crime, but then stopped. Wray suggested DOJ had lost its stomach for such things, hinting that he might “rectify” that.

Similarly, with the last questions of the hearing Mazie Hirono got the most important question about the process of Wray’s hiring answered, getting Wray to explain that only appropriate people (Trump, Don McGahn, Reince Priebus, Mike Pence) were in his two White House interviews.

But much of the rest of the hearing alternated between Wray’s obviously well-rehearsed promises he would never be pressured to shut down an investigation, alternating with a series of dodged questions. Those dodges included:

- What he did with the 2003 torture memo (dodge 1)

- Whether 702 should have more protections (dodge 2)

- Why did Trump fire Comey (dodge 3)

- To what extent the Fourth Amendment applies to undocumented people in the US (dodge 4)

- What we should do about junk science (dodge 5)

- Whether Don Jr should have taken a meeting with someone promising Russian government help to get Trump elected (dodge 6)

- Whether Lindsey Graham had fairly summarized the lies Don Jr told about his June 9, 2016 meeting (dodge 7)

- Can the President fire Robert Mueller (dodge 8)

- Whether it was a good idea to form a joint cyber group with Russia (dodge 9)

- The role of tech in terrorist recruitment (dodge 9 the second)

- Whether FBI Agents had lost faith in Comey (dodge 10)

- Who was in his White House interview — though this was nailed down in a Hirono follow up (dodge 11)

Now, don’t get me wrong, this kind of dodge ball is par for the course for executive branch nominees in this era of partisan bickering — it’s the safest way for someone who wants a job to avoid pissing anyone off.

But at this time of crisis, we can’t afford the same old dodge ball confirmation hearing.

Moreover, two of the these dodges are inexcusable, in my opinion. First, his non-responses on 702. That’s true, first of all, because if and when he is confirmed, he will have to jump into the reauthorization process right away, and those who want basic reforms let Wray off the hook on an issue they could have gotten commitments on. I also find it inexcusable because Wray plead ignorance about 702 even though he played a key role in (not) giving defendants discovery on Stellar Wind, and otherwise was read into Stellar Wind after 2004, meaning he knows generally how PRISM works. He’s not ignorant of PRISM, and given how much I know about 702, he shouldn’t be ignorant of that, either.

But the big one — the absolutely inexcusable non answer that would lead me to vote against him — is his claim not to know the law about whether the President can fire Robert Mueller himself.

Oh, sure, as FBI Director, Wray won’t be in the loop in any firing. But by not answering a question the answer to which most people watching the hearing had at least looked up, Wray avoided going on the record on an issue that could immediately put him at odds with Trump, the guy who thinks Wray should report directly to him.

Add to that the Committee’s failure to ask Wray two other questions I find pertinent (and his answers on David Passaro’s prosecution either revealed cynical deceit about his opposition to torture or lack of awareness of what really happened with that prosecution).

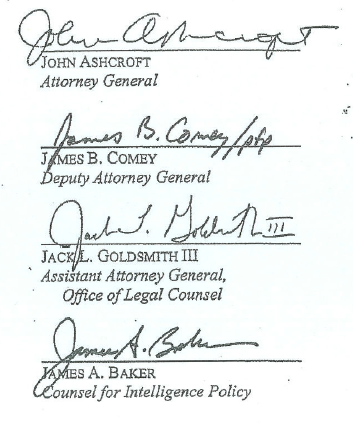

The first question Wray should have been asked (and I thought would have been by Al Franken, who instead asked no questions) is the circumstances surrounding Wray’s briefing of John Ashcroft about the CIA Leak investigation in 2003, including details on Ashcroft’s close associate Karl Rove’s role in exposing Valerie Plame’s identity.

Sure, at some level, Wray was just briefing his boss back in 2003 when he gave Ashcroft details he probably shouldn’t have. The fault was Ashcroft’s, not Wray’s. But being willing to give an inappropriate briefing in 2003 is a near parallel to where Comey found himself, being questioned directly by Trump on a matter which Trump shouldn’t have had access to. And asking Wray to explain his past actions is a far, far better indication of how he would act in the (near) future than his rehearsed assurances he can’t be pressured.

The other question I’d have loved Wray to get asked (though this is more obscure) is how, as Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division under Bush, he implemented the July 22, 2002 Jay Bybee memo permitting the sharing of grand jury information directly with the President and his top advisors without notifying the district court of that sharing. I’d have asked Wray this question because it was something he would have several years of direct involvement with (potentially even with the Plame investigation!), and it would serve as a very good stand-in for his willingness to give the White House an inappropriate glimpse into investigations implicating the White House.

There are plenty more questions (about torture and the Chiquita settlement, especially) I’d have liked Wray to answer.

But in spite of Wray’s many rehearsed assurances he won’t spike any investigation at the command of Donald Trump, he dodged (and was not asked) key questions that would have made him prove that with both explanations of his past actions and commitments about future actions.

Given Trump’s direct assault on prosecutorial independence, an assault he launched while clearly looking forward to having Wray in place instead of McCabe, the Senate should go back and get answers. Trump has suggested he thinks Wray will be different than Sessions, Rosenstein, Comey, and McCabe. And before confirming Wray, the Senate should find out whether Trump has a reason to believe that.

Update: I did not realize that between the time I started this while you were all asleep and the time I woke up in middle of the night Oz time SJC voted Wray out unanimously, which is a testament to the absolute dearth of oversight in the Senate.