The Internet Dragnet Was a Clusterfuck … and NSA Didn’t Care

Here’s my best description from last year of the mind-boggling fact that NSA conducted 25 spot checks between 2004 and 2009 and then did a several months’ long end-to-end review of the Internet dragnet in 2009 and found it to be in pretty good shape, only then to have someone discover that every single record received under the program had violated rules set in 2004.

Exhibit A is a comprehensive end-to-end report that the NSA conducted in late summer or early fall of 2009, which focused on the work the agency did in metadata collection and analysis to try and identify people emailing terrorist suspects.

The report described a number of violations that the NSA had cleaned up since the beginning of that year — including using automatic alerts that had not been authorized and giving the FBI and CIA direct access to a database of query results. It concluded the internet dragnet was in pretty good shape. “NSA has taken significant steps designed to eliminate the possibility of any future compliance issues,” the last line of the report read, “and to ensure that mechanisms are in place to detect and respond quickly if any were to occur.”

But just weeks later, the Department of Justice informed the FISA Court, which oversees the NSA program, that the NSA had been collecting impermissible categories of data — potentially including content — for all five years of the program’s existence.

The Justice Department said the violation had been discovered by NSA’s general counsel, which since a previous violation in 2004 had been required to do two spot checks of the data quarterly to make sure NSA had complied with FISC orders. But the general counsel had found the problem only after years of not finding it. The Justice Department later told the court that “virtually every” internet dragnet record “contains some metadata that was authorized for collection and some metadata that was not authorized for collection.” In other words, in the more than 25 checks the NSA’s general counsel should have done from 2004 to 2009, it never once found this unauthorized data.

The following year, Judge John Bates, then head of FISC, emphasized that the NSA had missed the unauthorized data in its comprehensive report. He noted “the extraordinary fact that NSA’s end-to-end review overlooked unauthorized acquisitions that were documented in virtually every record of what was acquired.” Bates went on, “[I]t must be added that those responsible for conducting oversight at NSA failed to do so effectively.”

Even after these details became public in 2014 (or perhaps because the intelligence community buried such disclosures in documents with dates obscured), commentators have generally given the NSA the benefit of the doubt in its good faith to operate its dragnet(s) under the rules set by the FISA Court.

But an IG Report from 2007 (PDF 24-56) released in Charlie Savage’s latest FOIA return should disabuse commentators of that opinion.

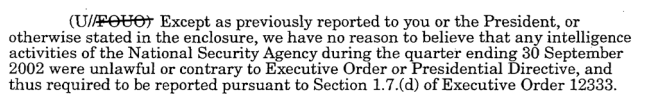

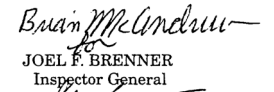

This is a report from early 2007, almost 3 years after the Stellar Wind Internet dragnet moved under FISA authority and close to 30 months after Judge Colleen Kollar-Kotelly ordered NSA to implement more oversight measures, including those spot checks. We know that rough date because the IG Report post-dates the January 8, 2007 initiation of the FISC-spying compartment and it reflects 10 dragnet order periods of up to 90 days apiece (see page 21). So the investigation in it should date to no later than February 8, 2007, with the final report finished somewhat later. It was completed by Brian McAndrew, who served as Acting Inspector General from the time Joel Brenner left in 2006 until George Ellard started in 2007 (but who also got asked to sign at least one document he couldn’t vouch for in 2002, again as Acting IG).

The IG Report is bizarre. It gives the NSA a passing grade on what it assessed.

The management controls designed by the Agency to govern the collection, dissemination, and data security of electronic communications metadata and U.S. person information obtained under the Order are adequate and in several aspects exceed the terms of the Order.

I believe that by giving a passing grade, the IG made it less likely his results would have to get reported (for example, to the Intelligence Oversight Board, which still wasn’t getting reporting on this program, and probably also to the Intelligence Committees, which didn’t start getting most documentation on this stuff until late 2008) in any but a routine manner, if even that. But the report also admits it did not assess “the effectiveness of management controls[, which] will be addressed in a subsequent report.” (The 2011 report examined here identified previous PRTT reports, including this one, and that subsequent report doesn’t appear in any obvious form.) Then, having given the NSA a passing grade but deferring the most important part of the review, the IG notes “additional controls are needed.”

And how.

As to the issue of the spot checks, mandated by the FISA Court and intended to prevent years of ongoing violations, the IG deems such checks “largely ineffective” because management hadn’t adopted a methodology for those spot checks. They appear to have just swooped in and checked queries already approved by an analyst’s supervisor, in what they called a superaudit.

Worse still, they didn’t write anything down.

As mandated by the Order, OGC periodically conducts random spot checks of the data collected [redaction] and monitors the audit log function. OGC does not, however document the data, scope, or results of the reviews. The purpose of the spot checks is to ensure that filters and other controls in place on the [redaction] are functioning as described by the Order and that only court authorized data is retained. [snip] Currently, an OGC attorney meets with the individuals responsible [redaction] and audit log functions, and reviews samples of the data to determine compliance with the Order. The attorney stated that she would formally document the reviews only if there were violations or other discrepancies of note. To date, OGC has found no violations or discrepancies.

So this IG review was done more than two years after Kollar-Kotelly had ordered these spot checks, during which period 18 spot checks should have been done. Yet at that point, NSA had no documentary evidence a single spot check had been done, just the say-so of the lawyer who claimed to have done them.

Keep in mind, too, that Oversight and Control were, at this point, implementing a new-and-improved spot-check process. That’s what the IG reviewed, the new-and-improved process, because (of course) reviewers couldn’t review the past process because there was no documentation of it. It’s the new-and-improved process that was inadequate to the task.

But that’s not the only problem the IG found in 2007. For example, the logs used in auditing did not accurately document what seed had been used for queries, which means you couldn’t review whether those queries really met the incredibly low bar of Reasonable Articulable Suspicion or that they were pre-approved. Nor did they document how many hops out analysts chained, which means any given query could have sucked in a great deal of Americans (which might happen by the third or fourth hop) and thrown them into the corporate store for far more intrusive anlaysis. While the IG didn’t point this out directly, the management response made clear log files also didn’t document whether a seed was a US person and therefore entitled to a First Amendment review. In short, NSA didn’t capture any — any!!! — of the data that would have been necessary to assess minimal compliance with FISC orders.

NSA’s lawyers also didn’t have a solid list of everyone who had access to the databases (and therefore who needed to be trained or informed of changes to the FISC order). The Program Management Office had a list that it periodically compared to who was actually accessing the data (though as made clear later in the report, that included just the analysts). And NSA’s Office of General Counsel would also periodically review to ensure those accessing the data had the information they needed to do so legally. But “the attorney conducting the review relie[d] on memory to verify the accuracy and completeness of the list.” DOD in general is wonderfully neurotic about documenting any bit of training a given person has undergone, but with the people who had access to the Internet metadata documenting a great deal of Americans’ communication in the country, NSA chose just to work from memory.

And this non-existent manner of tracking those with database access extended to auditing as well. The IG reported that NSA also didn’t track all queries made, such as those made by “those that have the ability to query the PRTT data but are not on the PMO list or who are not analysts.” While the IG includes people who’ve been given new authorization to query the data in this discussion, it’s also talking about techs who access the data. It notes, for example, “two systems administrators, who have the ability to query PRTT data, were also omitted from the audit report logs.” The thing is, as part of the 2009 “reforms,” NSA got approval to exempt techs from audits. I’ve written a lot about this but will return to it, as there is increasing evidence that the techs have always had the ability — and continue to have the ability — to bypass limits on the program.

There are actually far more problems reported in this short report, including details proving that — as I’ve pointed out before — NSA’s training sucks.

But equally disturbing is the evidence that NSA really didn’t give a fuck about the fact they’d left a database of a significant amount of Americans’ communications metadata exposed to all sorts of control problems. The disinterest in fixing this problem dates back to 2004, when NSA first admitted to Kollar-Kotelly they were violating her orders. They did an IG report at the time (under the guidance of Joel Brenner), but it did “not make formal recommendations to management. Rather, the report summarize[d] key facts and evaluate[d] responsibility for the violation.” That’s unusual by itself: for audits to improve processes, they are supposed to provide recommendations and track whether those are implemented. Moreover, while the IG (who also claimed the clusterfuck in place in 2007 merited a passing grade) assessed that “management has taken steps to prevent recurrence of the violation,” it also noted that NSA never really fixed the monitoring and change control process identified as problems back in 2004. In other words, it found that NSA hadn’t fixed key problems IDed back in 2004.

As to this report? It did make recommendations and management even concurred with some of them, going so far as to agree to document (!!) their spot checks in the future. With others — such as the recommendation that shift supervisors should not be able to make their own RAS determinations — management didn’t concur, they just said they’d monitor those queries more closely in the future. As to the report as a whole, here’s what McAndrew had to say about management’s response to the report showing the PRTT program was a clusterfuck of vulnerabilities: “Because of extenuating circumstances, management was unable to provide complete responses to the draft report.”

So in 2007, NSA’s IG demonstrated that the oversight over a program giving NSA access to the Internet metadata of a good chunk of all Americans was laughably inadequate.

And NSA’s management didn’t even bother to give the report a full response.