The FBI (or NSA?)’s Bulk National Security Letters

Say, did you notice that the NSA Review Group, like the Leahy-Sensenbrenner bill before it, endorsed dramatic restrictions on National Security Letters?

Both efforts set out to address the most extreme privacy risks posed by — the perception was — the NSA, yet both would impose new rules on NSLs, which are primarily used by the FBI. And both efforts would attempt to at least limit (and therefore presumably end) any bulk collection with NSLs.

Leahy-Sensenbrenner provides specific changes to both the statute authorizing communications collection and the one authorizing financial data collection. In the case of toll records, the changes look like this:

Required Certification.— The Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, or his designee in a position not lower than Deputy Assistant Director at Bureau headquarters or a Special Agent in Charge in a Bureau field office designated by the Director may request the name, address, length of service, and local and long distance toll billing records of a person or entity if the Director (or his designee) certifies in writing to the wire or electronic communication service provider to which the request is made that—

(1) the name, address, length of service, and toll billing records sought are relevant and material to an authorized investigation to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities, provided that such an investigation of a United States person is not conducted solely on the basis of activities protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States; and

(2) there are reasonable grounds to believe that the name, address, length of service, and toll billing records sought pertain to—

(A) a foreign power or agent of a foreign power;

(B) the activities of a suspected agent of a foreign power who is the subject of such authorized investigation; or

(C) an individual in contact with, or known to, a suspected agent of a foreign power. [my emphasis]

In addition, Leahy-Sensenbrenner would make NSL gags harder to sustain.

The Review Group went even further with respect to the basic NSL requests. It recommended (as its 2nd and 3rd recommendations, stuck right in the middle of its Section 215 discussion!) not only limiting bulk collection with NSLs, but requiring judicial review and adding minimization procedures to them.

Recommendation 2 We recommend that statutes that authorize the issuance of National Security Letters should be amended to permit the issuance of National Security Letters only upon a judicial finding that:

(1) the government has reasonable grounds to believe that the particular information sought is relevant to an authorized investigation intended to protect “against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities” and

(2) like a subpoena, the order is reasonable in focus, scope, and breadth.

Recommendation 3 We recommend that all statutes authorizing the use of National Security Letters should be amended to require the use of the same oversight, minimization, retention, and dissemination standards that currently govern the use of section 215 orders. [my emphasis]

There are two possible reasons why Leahy-Sensenbrenner and the Review Group would offer such similar reforms. First, it’s possible they worry that limiting bulk collection on Section 215 without limiting it on NSLs would lead the government to use NSLs instead.

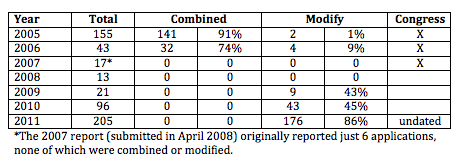

Far more likely, both would propose such reforms because they know NSLs had already been used for bulk collection. (We know DOJ used bulk NSLs in its efforts to fix its exigent letter problems, but that involved just 3 bulk orders, all 3 issued in 2006.)

Which would be alarming because — as the Review Group points out — in FY2012 (which extends from October 1, 2011 to September 30, 2012), the FBI issued 21,000 NSLs, “primarily for subscriber information.” DOJ’s reports to Congress reported 16,511 NSL requests in 2011 and 15,229 in 2012 that weren’t subscriber information only, so roughly 5,500 of that 21,000 were just subscriber information. But the FBI could very well be issuing bulk orders for both toll records and financial records.

That’s a lot of potential bulk orders.

And, as the Review Group makes clear in its list of reasons the NSLs are ripe for abuse, the FBI doesn’t treat this data with the same care that NSA purportedly treats the phone dragnet data.

[T]he oversight and minimization requirements governing the use of NSLs are much less rigorous than those imposed in the use of section 215 orders.

So data from potentially thousands of bulk orders, covering both toll and financial records, may be sitting on FBI’s servers, with few access, dissemination, and age-off restrictions.

No wonder the Review Group thinks the NSLs should be subject to the same kind of judicial scrutiny as the other laws repurposed for bulk collection.

There is one final—and important— issue about NSLs. For all the well-established reasons for requiring neutral and detached judges to decide when government investigators may invade an individual’s privacy, there is a strong argument that NSLs should not be issued by the FBI itself. Although administrative subpoenas are often issued by administrative agencies, foreign intelligence investigations are especially likely to implicate highly sensitive and personal information and to have potentially severe consequences for the individuals under investigation. We are unable to identify a principled reason why NSLs should be issued by FBI officials when section 215 orders and orders for pen register and trap-and-trace surveillance must be issued by the FISC.

Which is precisely the reason why the Administration is fighting this.

While the focus on reforms Obama may reject has centered on the phone dragnet collection, anonymous sources are also saying the government can’t accept the Review Group proposal for NSLs.

Civil liberties groups would like Obama to rein in the government’s use of so-called “national security letters,” which allow the FBI and other agencies to compel individuals and organizations to turn over business records without any independent or judicial review.

A senior administration official said no final decisions had been made yet, but some operational agencies have concerns about limiting the use of these letters because it would raise the bar for intelligence investigations above that for criminal ones.

Which is understandable, so long as you ignore the high likelihood these are bulk orders. But once you imagine how many Americans’ records this might include if any significant number of NSLs are bulk orders, then it seems utterly shocking no judge reviews the requests.

That’s presumably one of the reasons the Administration wants to rush through its recommendations before we think too hard about the implications of bulk NSL orders.