In this post, I’m going to lay out the evidence needed to fully explain the Russian hack. I think it will help to explain some of the timing around the story that the CIA believes Russia hacked the DNC to help win Trump win the election, as well as what is new in Friday’s story. I will do rolling updates on this and eventually turn it into a set of pages on Russia’s hacking.

As I see it, intelligence on all the following are necessary to substantiate some of the claims about Russia tampering in this year’s election.

- FSB-related hackers hacked the DNC

- GRU-related hackers hacked the DNC

- Russian state actors hacked John Podesta’s emails

- Russian state actors hacked related targets, including Colin Powell and some Republican sites

- Russian state actors hacked the RNC

- Russian state actors released information from DNC and DCCC via Guccifer 2

- Russian state actors released information via DC Leaks

- Russian state actors or someone acting on its behest passed information to Wikileaks

- The motive explaining why Wikileaks released the DNC and Podesta emails

- Russian state actors probed voter registration databases

- Russian state actors used bots and fake stories to make information more damaging and magnify its effects

- The level at which all Russian state actors’ actions were directed and approved

- The motive behind the actions of Russian state actors

- The degree to which Russia’s efforts were successful and/or primary in leading to Hillary’s defeat

I explain all of these in more detail below. For what it’s worth, I think there was strong publicly available information to prove 3, 4, 7, 11. I think there is weaker though still substantial information to support 2. It has always been the case that the evidence is weakest at point 6 and 8.

At a minimum, to blame Russia for tampering with the election, you need high degree of confidence that GRU hacked the DNC (item 2), and shared those documents via some means with Wikileaks (item 8). What is new about Friday’s story is that, after months of not knowing how the hacked documents got from Russian hackers to Wikileaks, CIA now appears to know that people close to the Russian government transferred the documents (item 8). In addition, CIA now appears confident that all this happened to help Trump win the presidency (item 13).

1) FSB-related hackers hacked the DNC

The original report from Crowdstrike on the DNC hack actually said two separate Russian-linked entities hacked the DNC: one tied to the FSB, which it calls “Cozy Bear” or APT 29, and one tied to GRU, which it calls “Fancy Bear” or APT 28. Crowdstrike says Cozy Bear was also responsible for hacks of unclassified networks at the White House, State Department, and US Joint Chiefs of Staff.

I’m not going to assess the strength of the FSB evidence here. As I’ll lay out, the necessary hack to attribute to the Russians is the GRU one, because that’s the one believed to be the source of the DNC and Podesta emails. The FSB one is important to keep in mind, as it suggests part of the Russian government may have been hacking US sites solely for intelligence collection, something our own intelligence agencies believe is firmly within acceptable norms of spying. In the months leading up to the 2012 election, for example, CIA and NSA hacked the messaging accounts of a bunch of Enrique Peña Nieto associates, pretty nearly the equivalent of the Podesta hack, though we don’t know what they did with that intelligence. The other reason to keep the FSB hack in mind is because, to the extent FSB hacked other sites, they also may be deemed part of normal spying.

2) GRU-related hackers hacked the DNC

As noted, Crowdstrike reported that GRU also hacked the DNC. As it explains, GRU does this by sending someone something that looks like an email password update, but which instead is a fake site designed to get someone to hand over their password. The reason this claim is strong is because people at the DNC say this happened to them.

Note that there are people who raise questions of whether this method is legitimately tied to GRU and/or that the method couldn’t be stolen and replicated. I will deal with those questions at length elsewhere. But for the purposes of this post, I will accept that this method is a clear sign of GRU involvement. There are also reports that deal with GRU hacking that note high confidence GRU hacked other entities, but less direct evidence they hacked the DNC.

Finally, there is the real possibility that other people hacked the DNC, in addition to FSB and GRU. That possibility is heightened because a DNC staffer was hacked via what may have been another method, and because DNC emails show a lot of password changes off services for which DNC staffers had had their accounts exposed in other hacks.

All of which is a way of saying, there is some confidence that DNC got hacked at least twice, with those two revealed efforts being done by hackers with ties to the Russian state.

3) Russian state actors (GRU) hacked John Podesta’s emails

Again, assuming that the fake Gmail phish is GRU’s handiwork, there is probably the best evidence that GRU hacked John Podesta and therefore that Russia, via some means, supplied Wikileaks, because we have a copy of the actual email used to hack him. The Smoking Gun has an accessible story describing how all this works. So in the case of Podesta, we know he got a malicious phish email, we know that someone clicked the link in the email, and we know that emails from precisely that time period were among the documents shared with Wikileaks. We just have no idea how they got there.

4) Russian state actors hacked related targets, including some other Democratic staffers, Colin Powell and some Republican sites

That same Gmail phish was used with victims — including at a minimum William Rinehart and Colin Powell — that got exposed in a site called DC Leaks. We can have the same high degree of confidence that GRU conducted this hack as we do with Podesta. As I note below, that’s more interesting for what it tells us about motive than anything else.

5) Russian state actors hacked the RNC

The allegation that Russia also hacked the RNC, but didn’t leak those documents — which the CIA seems to rely on in part to argue that Russia must have wanted to elect Trump — has been floating around for some time. I’ll return to what we know of this. RNC spox Sean Spicer is denying it, though so did Hillary’s people at one point deny that they had been hacked.

There are several points about this. First, hackers presumed to be GRU did hack and release emails from Colin Powell and an Republican-related server. The Powell emails (including some that weren’t picked up in the press), in particular, were detrimental to both candidates. The Republican ones were, like a great deal of the Democratic ones, utterly meaningless from a news standpoint.

So I don’t find this argument persuasive in its current form. But the details on it are still sketchy precisely because we don’t know about that hack.

6) Russian state actors released information from DNC and DCCC via Guccifer 2

Some entity going by the name Guccifer 2 started a website in the wake of the announcement that the DNC got hacked. The site is a crucial part of this assessment, both because it released DNC and DCCC documents directly (though sometimes misattributing what it was releasing) and because Guccifer 2 stated clearly that he had shared the DNC documents with Wikileaks. The claim has always been that Guccifer 2 was just a front for Russia — a way for them to adopt plausible deniability about the DNC hack.

That may be the case (and obvious falsehoods in Guccifer’s statements make it clear deception was part of the point), but there was always less conclusive (and sometimes downright contradictory) evidence to support this argument (this post summarizes what it claims are good arguments that Guccifer 2 was a front for Russia; on the most part I disagree and hope to return to it in the future). Moreover, this step has been one that past reporting said the FBI couldn’t confirm. Then there are other oddities about Guccifer’s behavior, such as his “appearance” at a security conference in London, or the way his own production seemed to fizzle as Wikileaks started releasing the Podesta emails. Those details of Guccifer’s behavior are, in my opinion, worth probing for a sense of how all this was orchestrated.

Yesterday’s story seems to suggest that the spooks have finally figured out this step, though we don’t have any idea what it entails.

7) Russian state actors released information via DC Leaks

Well before many people realized that DC Leaks existed, I suspected that it was a Russian operation. That’s because two of its main targets — SACEUR Philip Breedlove and George Soros — are targets Russia would obviously hit to retaliate for what it treats as a US-backed coup in Ukraine.

DC Leaks is also where the publicly released (and boring) GOP emails got released.

Perhaps most importantly, that’s where the Colin Powell emails got released (this post covers some of those stories). That’s significant because Powell’s emails were derogatory towards both candidates (though he ultimately endorsed Hillary).

It’s interesting for its haphazard targeting (if someone wants to pay me $$ I would do an assessment of all that’s there, because some just don’t make any clear sense from a Russian perspective, and some of the people most actively discussing the Russian hacks have clearly not even read all of it), but also because a number of the victims have been affirmatively tied to the GRU phishing methods.

So DC Leaks is where you get obvious Russian targets and Russian methods all packaged together. But of the documents it released, the Powell emails were the most interesting for electoral purposes, and they didn’t target Hillary as asymmetrically as the Wikileaks released documents did.

8) Russian state actors or someone acting on its behest passed information to Wikileaks

The basis for arguing that all these hacks were meant to affect the election is that they were released via Wikileaks. That is what was supposed to be new, beyond just spying (though we have almost certainly hacked documents and leaked them, most probably in the Syria Leaks case, but I suspect also in some others).

And as noted, how Wikileaks got two separate sets of emails has always been the big question. With the DNC emails, Guccifer 2 clearly said he had given them to WL, but the Guccifer 2 ties to Russia was relatively weak. And with the Podesta emails, I’m not aware of any known interim step between the GRU hack and Wikileaks.

A late July report said the FBI was still trying to determine how Russia got the emails to Wikileaks or even if they were the same emails.

The FBI is still investigating the DNC hack. The bureau is trying to determine whether the emails obtained by the Russians are the same ones that appeared on the website of the anti-secrecy group WikiLeaks on Friday, setting off a firestorm that roiled the party in the lead-up to the convention.

The FBI is also examining whether APT 28 or an affiliated group passed those emails to WikiLeaks, law enforcement sources said.

An even earlier report suggested that the IC wasn’t certain the files had been passed electronically.

And the joint DHS/ODNI statement largely attributed its confidence that Russia was involved in the the leaking (lumping Guccifer 2, DC Leaks, and Wikileaks all together) not because it had high confidence in that per se (a term of art saying, effectively, “we have seen the evidence”), but instead because leaking such files is consistent with what Russia has done elsewhere.

The recent disclosures of alleged hacked e-mails on sites like DCLeaks.com and WikiLeaks and by the Guccifer 2.0 online persona are consistent with the methods and motivations of Russian-directed efforts.

Importantly, that statement came out on October 7, so well after the September briefing at which CIA claimed to have further proof of all this.

Now, Julian Assange has repeatedly denied that Russia was his source. Craig Murray asserted, after having meeting with Assange, that the source is not the Russian state or a proxy. Wikileaks’ tweet in the wake of yesterday’s announcement — concluding that an inquiry directed at Russia in this election cycle is targeted at Wikileaks — suggests some doubt. Also, immediately after the election, Sergei Markov, in a statement deemed to be consistent with Putin’s views, suggested that “maybe we helped a bit with WikiLeaks,” even while denying Russia carried out the hacks.

That’s what’s new in yesterday’s story. It stated that “individuals with connections to the Russian government” handed the documents to Wikileaks.

Intelligence agencies have identified individuals with connections to the Russian government who provided WikiLeaks with thousands of hacked emails from the Democratic National Committee and others, including Hillary Clinton’s campaign chairman, according to U.S. officials. Those officials described the individuals as actors known to the intelligence community and part of a wider Russian operation to boost Trump and hurt Clinton’s chances.

[snip]

[I]ntelligence agencies do not have specific intelligence showing officials in the Kremlin “directing” the identified individuals to pass the Democratic emails to WikiLeaks, a second senior U.S. official said. Those actors, according to the official, were “one step” removed from the Russian government, rather than government employees. Moscow has in the past used middlemen to participate in sensitive intelligence operations so it has plausible deniability.

I suspect we’ll hear more leaked about these individuals in the coming days; obviously, the IC says it doesn’t have evidence of the Russian government ordering these people to share the documents with Wikileaks.

Nevertheless, the IC now has what it didn’t have in July: a clear idea of who gave Wikileaks the emails.

9) The motive explaining why Wikileaks released the DNC and Podesta emails

There has been a lot of focus on why Wikileaks did what it did, which notably includes timing the DNC documents to hit for maximum impact before the Democratic Convention and timing the Podesta emails to be a steady release leading up to the election.

I don’t rule out Russian involvement with all of that, but it is entirely unnecessary in this case. Wikileaks has long proven an ability to hype its releases as much as possible. More importantly, Assange has reason to have a personal gripe against Hillary, going back to State’s response to the cable release in 2010 and the subsequent prosecution of Chelsea Manning.

In other words, absent really good evidence to the contrary, I assume that Russia’s interests and Wikileaks’ coincided perfectly for this operation.

10) Russian state actors probed voter registration databases

Back in October, a slew of stories reported that “Russians” had breached voter related databases in a number of states. The evidence actually showed that hackers using a IP tied to Russia had done these hacks. Even if the hackers were Russian (about which there was no evidence in the first reports), there was also no evidence the hackers were tied to the Russian state. Furthermore, as I understand it, these hacks used a variety of methods, some or all of which aren’t known to be GRU related. A September DHS bulletin suggested these hacks were committed by cybercriminals (in the past, identity thieves have gone after voter registration lists). And the October 7 DHS/ODNI statement affirmatively said the government was not attributing the probes to the Russians.

Some states have also recently seen scanning and probing of their election-related systems, which in most cases originated from servers operated by a Russian company. However, we are not now in a position to attribute this activity to the Russian Government.

In late November, an anonymous White House statement said there was no increased malicious hacking aimed at the electoral process, though remains agnostic about whether Russia ever planned on such a thing.

The Federal government did not observe any increased level of malicious cyber activity aimed at disrupting our electoral process on election day. As we have noted before, we remained confident in the overall integrity of electoral infrastructure, a confidence that was borne out on election day. As a result, we believe our elections were free and fair from a cybersecurity perspective.

That said, since we do not know if the Russians had planned any malicious cyber activity for election day, we don’t know if they were deterred from further activity by the various warnings the U.S. government conveyed.

Absent further evidence, this suggests that reports about Russian trying to tamper with the actual election infrastructure were at most suspicions and possibly just a result of shoddy reporting conflating Russian IP with Russian people with Russian state.

11) Russian state actors used bots and fake stories to make information more damaging and magnify its effects

Russia has used bots and fake stories in the past to distort or magnify compromising information. There is definitely evidence some pro-Trump bots were based out of Russia. RT and Sputnik ran with inflammatory stories. Samantha Bee famously did an interview with some Russians who were spreading fake news. But there were also people spreading fake news from elsewhere, including Macedonia and Surburban LA. A somewhat spooky guy even sent out fake news in an attempt to discredit Wikileaks.

As I have argued, the real culprit in this economy of clickbait driven outrage is closer to home, in the algorithms that Silicon Valley companies use that are exploited by a whole range of people. So while Russian directed efforts may have magnified inflammatory stories, that was not a necessary part of any intervention in the election, because it was happening elsewhere.

12) The level at which all Russian state actors’ actions were directed and approved

The DHS/ODNI statement said clearly that “We believe, based on the scope and sensitivity of these efforts, that only Russia’s senior-most officials could have authorized these activities.” But the WaPo story suggests they still don’t have proof of Russia directing even the go-between who gave WL the cables, much less the go-between directing how Wikileaks released these documents.

Mind you, this would be among the most sensitive information, if the NSA did have proof, because it would be collection targeted at Putin and his top advisors.

13) The motive behind the actions of Russian state actors

The motive behind all of this has varied. The joint DHS/ODNI statement said it was “These thefts and disclosures are intended to interfere with the US election process.” It didn’t provide a model for what that meant though.

Interim reporting — including the White House’s anonymous post-election statement — had suggested that spooks believed Russia was doing it to discredit American democracy.

The Kremlin probably expected that publicity surrounding the disclosures that followed the Russian Government-directed compromises of e-mails from U.S. persons and institutions, including from U.S. political organizations, would raise questions about the integrity of the election process that could have undermined the legitimacy of the President-elect.

At one level, that made a lot of sense — the biggest reason to release the DNC and Podesta emails, it seems to me, was to confirm the beliefs a lot of people already had about how power works. I think one of the biggest mistakes of journalists who have political backgrounds was to avoid discussing how the sausage of politics gets made, because this material looks worse if you’ve never worked in a system where power is about winning support. All that said, there’s nothing in the emails (especially given the constant release of FOIAed emails) that uniquely exposed American democracy as corrupt.

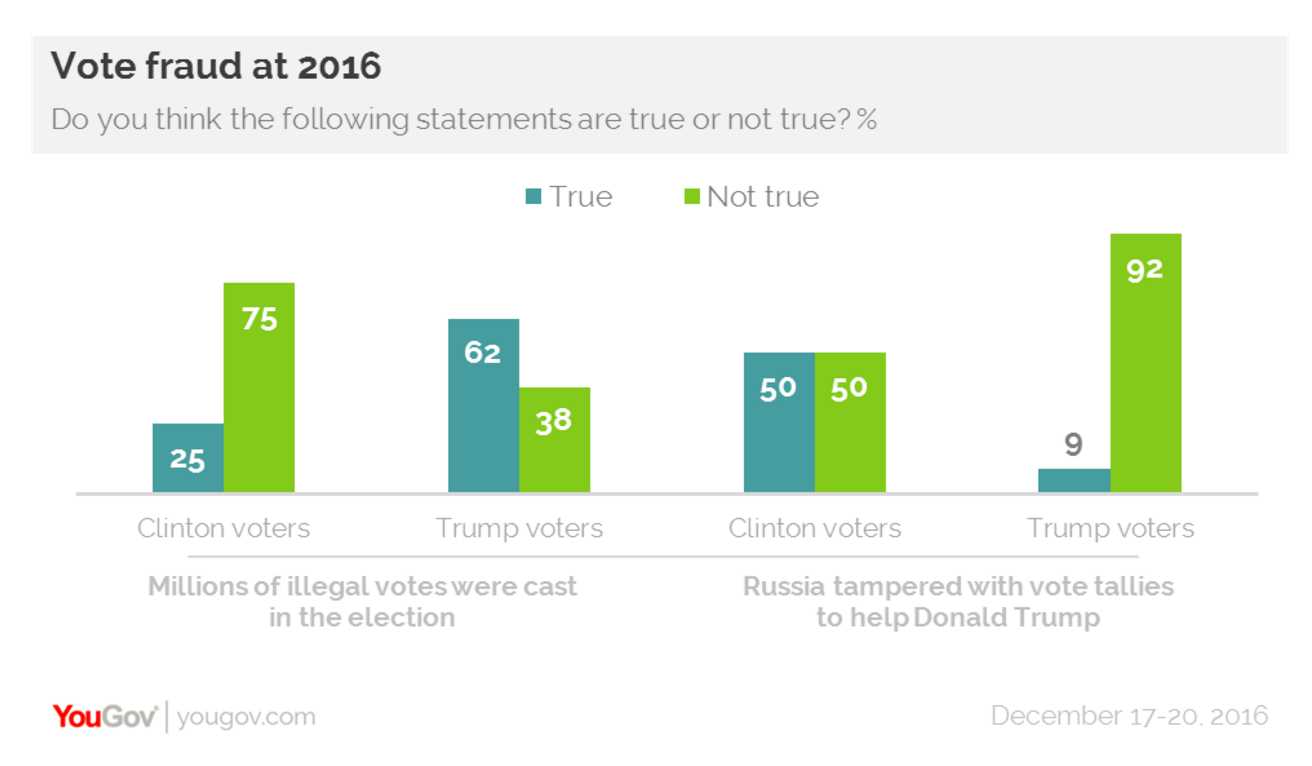

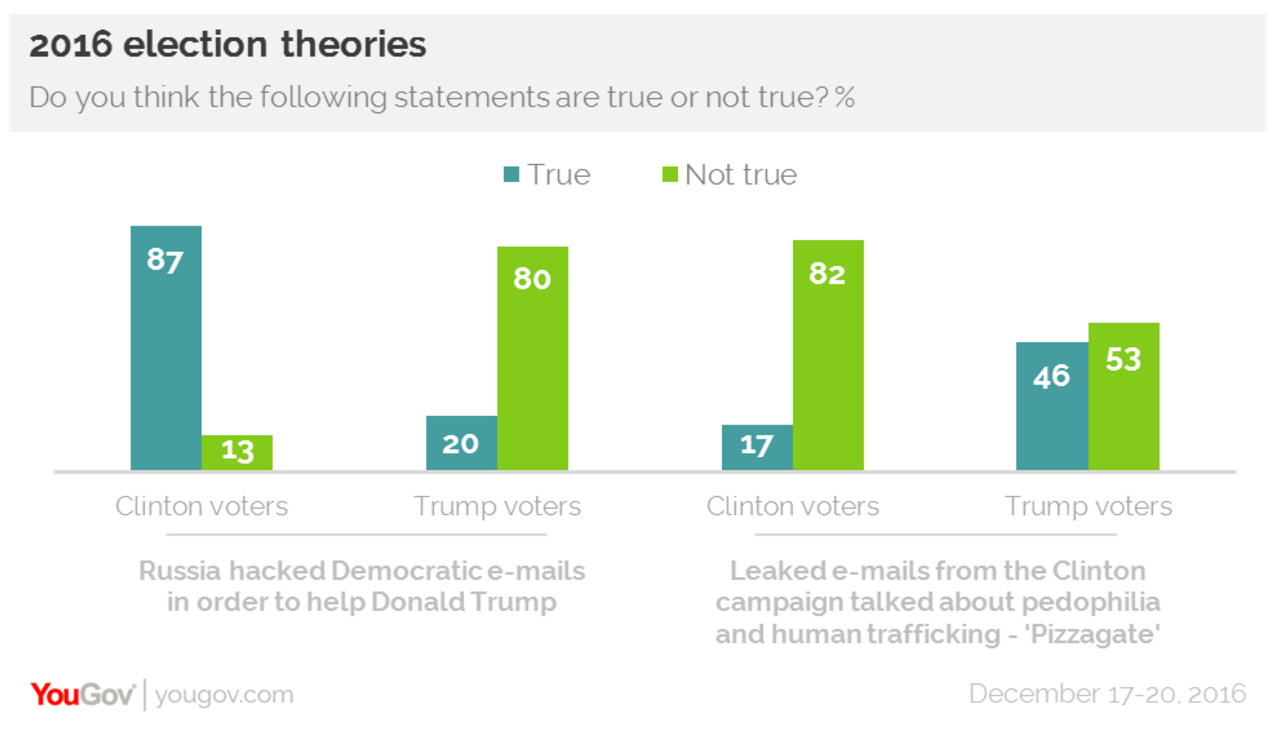

All of which is to say that this explanation never made any sense to me; it was mostly advanced by people who live far away from people who already distrust US election systems, who ignored polls showing there was already a lot of distrust.

Which brings us to the other thing that is new in the WaPo story: the assertion that CIA now believes this was all intended to elect Trump, not just make us distrust elections.

The CIA has concluded in a secret assessment that Russia intervened in the 2016 election to help Donald Trump win the presidency, rather than just to undermine confidence in the U.S. electoral system, according to officials briefed on the matter.

[snip]

“It is the assessment of the intelligence community that Russia’s goal here was to favor one candidate over the other, to help Trump get elected,” said a senior U.S. official briefed on an intelligence presentation made to U.S. senators. “That’s the consensus view.”

For what it’s worth, there’s still some ambiguity in this. Did Putin really want Trump? Or did he want Hillary to be beat up and weak for an expected victory? Did he, like Assange, want to retaliate for specific things he perceived Hillary to have done, in both Libya, Syria, and Ukraine? That’s unclear.

14) The degree to which Russia’s efforts were successful and/or primary in leading to Hillary’s defeat

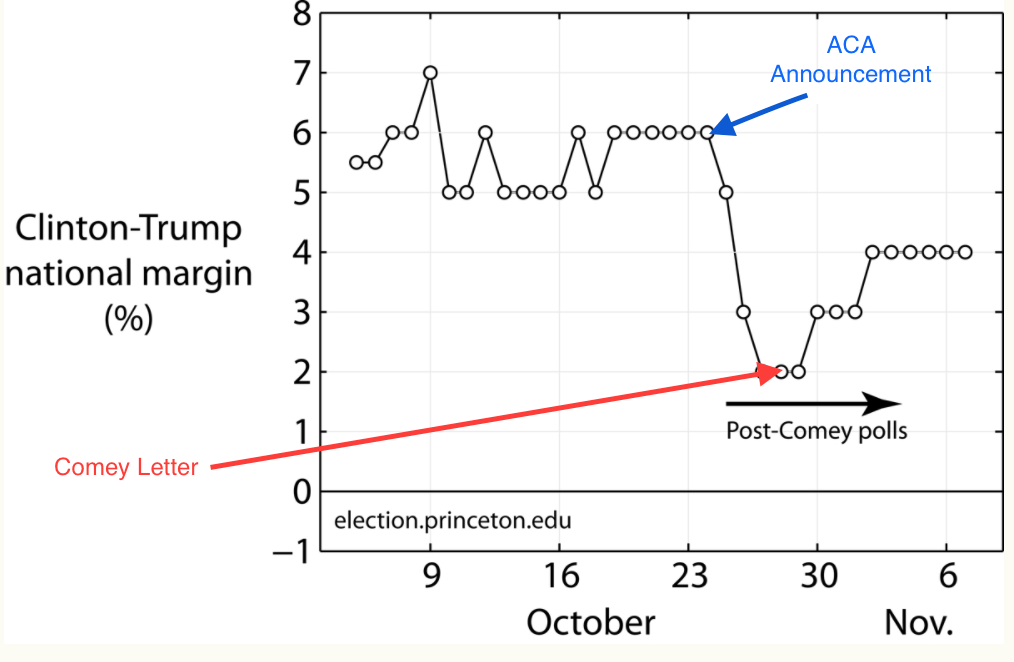

Finally, there’s the question that may explain Obama’s reticence about this issue, particularly in the anonymous post-election statement from the White House, which stated that the “election results … accurately reflect the will of the American people.” It’s not clear that Putin’s intervention, whatever it was, had anywhere near the effect as (for example) Jim Comey’s letters and Bret Baier’s false report that Hillary would be indicted shortly. There are a lot of other factors (including Hillary’s decision to ignore Jake Sullivan’s lonely advice to pay some attention to the Rust Belt).

And, as I’ve noted repeatedly, it is no way the case that Vladimir Putin had to teach Donald Trump about kompromat, the leaking of compromising information for political gain. Close Trump associates, including Roger Stone (who, by the way, may have had conversations with Julian Assange), have been rat-fucking US elections since the time Putin was in law school.

But because of the way this has rolled out (and particularly given the cabinet picks Trump has already made), it will remain a focus going forward, perhaps to the detriment of other issues that need attention.