Stephen Miller Claims that Trump’s Russian Investigation Line Was a Disclaimer

In this post, I noted that Trump (in his interview with the WSJ) appears to believe asking for and getting a letter from Rod Rosenstein justifying Jim Comey’s firing is proof that his firing of Comey wasn’t obstruction of justice. I suggested that that argument may have been planned from the start — and noted the proximity of that argument to the claim, which we know Jared Kushner provided, that Democrats would be thrilled by Comey’s firing.

Having suggested that there was more of a plan behind the orchestrated firing of Comey than we might imagine, I want to return to the Jake Tapper interview with Stephen Miller on Sunday.

Tapper asked Miller about his role in writing the initial draft of the letter that fired Comey, which NYT reported on this way:

Mr. McGahn successfully blocked the president from sending the letter — which Mr. Trump had composed with Stephen Miller, one of the president’s top political advisers — to Mr. Comey. But a copy was given to the deputy attorney general, Rod J. Rosenstein, who then drafted his own letter. Mr. Rosenstein’s letter was ultimately used as the Trump administration’s public rationale for Mr. Comey’s firing, which was that Mr. Comey had mishandled the investigation into Hillary Clinton’s private email server.

Mr. Rosenstein is overseeing Mr. Mueller’s investigation into Russian efforts to disrupt last year’s presidential election, as well as whether Mr. Trump obstructed justice.

Mr. McGahn’s concerns about Mr. Trump’s letter show how much he realized that the president’s rationale for firing Mr. Comey might not hold up to scrutiny, and how he and other administration officials sought to build a more defensible public case for his ouster.

[snip]

Mr. Trump ordered Mr. Miller to draft a letter, and dictated his unfettered thoughts. Several people who saw Mr. Miller’s multi-page draft described it as a “screed.”

Mr. Trump was back in Washington on Monday, May 8, when copies of the letter were handed out in the Oval Office to senior officials, including Mr. McGahn and Vice President Mike Pence. Mr. Trump announced that he had decided to fire Mr. Comey, and read aloud from Mr. Miller’s memo.

Some present at the meeting, including Mr. McGahn, were alarmed that the president had decided to fire the F.B.I. director after consulting only Ms. Trump, Mr. Kushner and Mr. Miller. Mr. McGahn began an effort to stop the letter or at least pare it back.

[snip]

Rosenstein was given a copy of the original letter and agreed to write a separate memo for Mr. Trump about why Mr. Comey should be fired.

In the interview with Tapper, Miller claimed that the key claim the NYT said got removed — about Comey thrice telling Trump he wasn’t personally under investigation — was actually in the final letter.

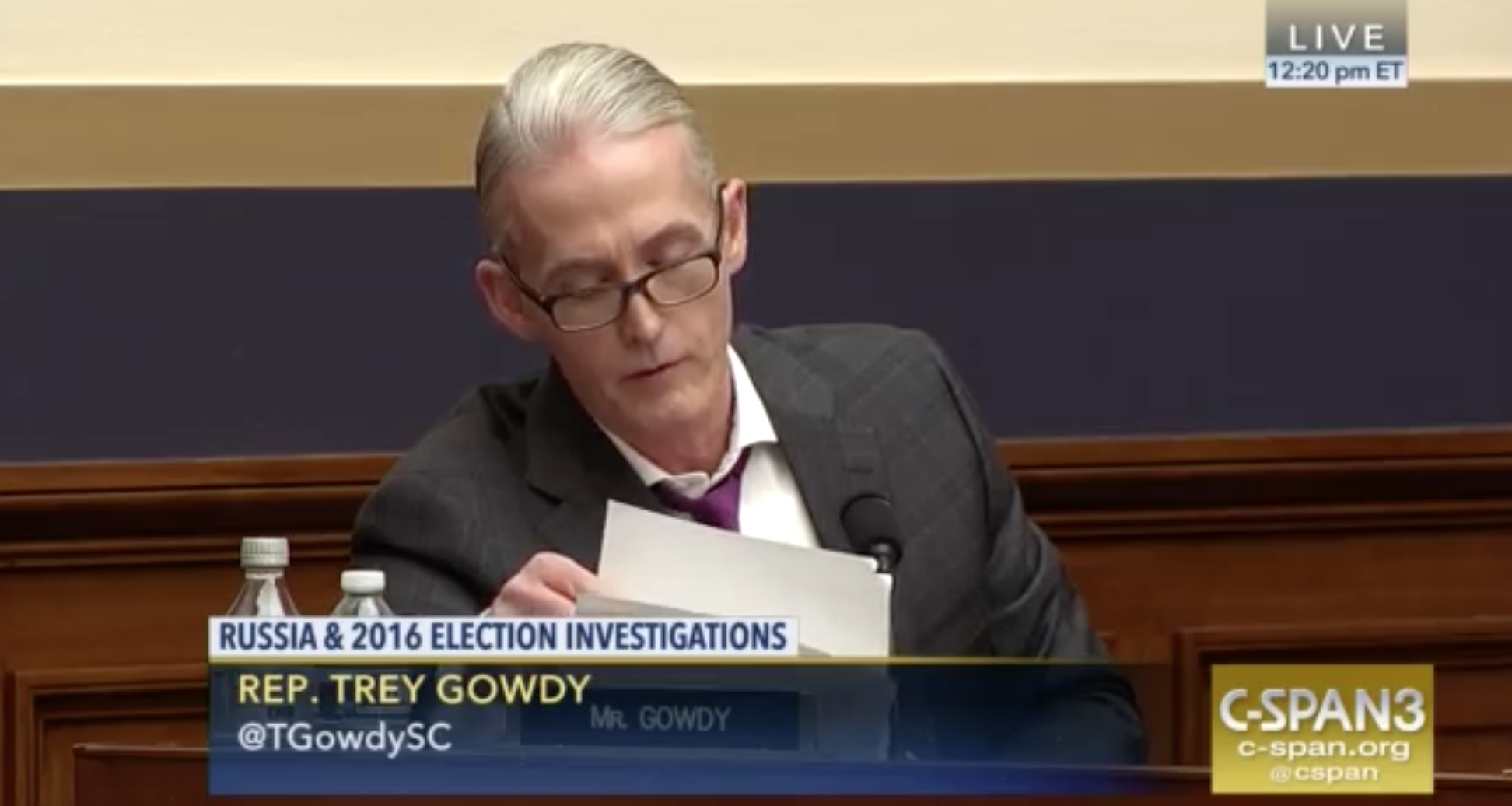

Tapper: According to the New York Times, Special Counsel Robert Mueller has, in his possession, an early draft of a letter that you helped write, in May 2017, detailing reasons to fire FBI Director James Comey. According to the newspaper, the first line of the letter mentions the Russia investigation. Did you write a letter outlining the reasons to fire Comey and list the Russia investigation. Is that true?

Miller: Here’s the problem with what you’re saying: the final draft of the letter the one that was made —

Tapper: I’m not talking about that one, I’m talking about the one that Comey [sic] has that mentions Russia —

Miller: If you want to have an answer to your question and not to get hysterical, then I’ll answer it. The final draft of the letter has the same line about the fact that there is a Trump-Russia investigation that this has nothing to do with.

Tapper: So it was just moved from the top to the bottom.

Miller: No. No! Look at the letter. It’s at the beginning. The investigation is referenced at the beginning of the final letter that was released to point out about the fact that notwithstanding, having been informed that there’s no investigation, that the um, the move that is happening is completely unrelated to that. So it was a disclaimer. It appeared in the final version of the letter that was made public.

Here’s the letter Trump sent to fire Comey. The passage Miller must be talking about reads,

While I greatly appreciate you informing me, on three separate occasions, that I am not under investigation, I nevertheless concur with the judgment of the Department of Justice that you are not able to effectively lead the Bureau.

That’s the passage that was so confounding when we all read that in real time.

And while I’m not prepared to believe Miller that that is the totality of the reference to Russia in the original letter — after all, this doesn’t even mention Russia — what I do think Miller provided proof for on national TV is that the connotation of that sentence changed from first to second draft, and in a way that he, Kushner, and Don McGahn all surely recognize.

In the first letter, according to McGahn and others, the “screed” listed the Russia investigation as a reason to fire Comey. Here, according to the guy who drafted it, it is meant to serve as a disclaimer, a denial that this firing was about the Russia investigation.

And that’s what Miller surely told Mueller’s investigators.

No wonder he kept ranting and had to be escorted off Tapper’s set. He just revealed, for everyone, how this second letter was designed to be misleading.

In the last week, Miller and Trump have told CNN and WSJ, respectively, about their cover-up.

Update: I forgot to reference this language from the NYT’s latest. The line originally said that the investigation was“fabricated and politically motivated.” If that reporting is correct then they also changed the wording of the reference to the investigation.