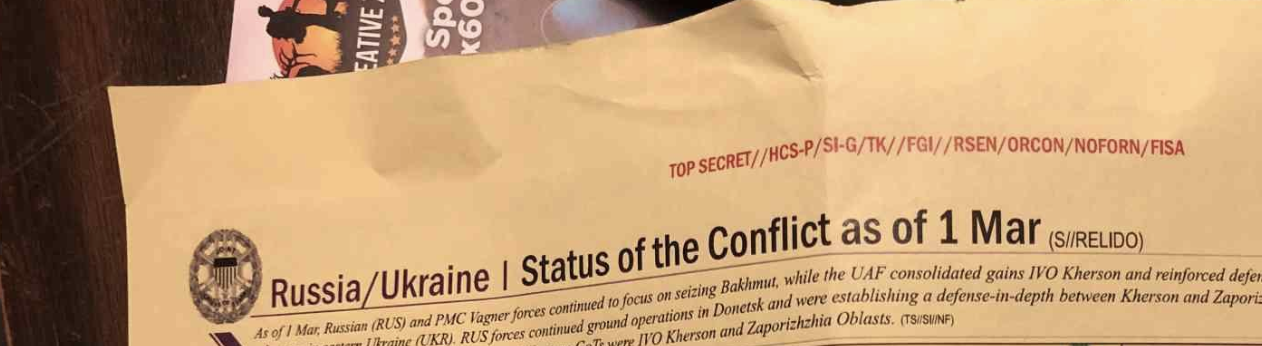

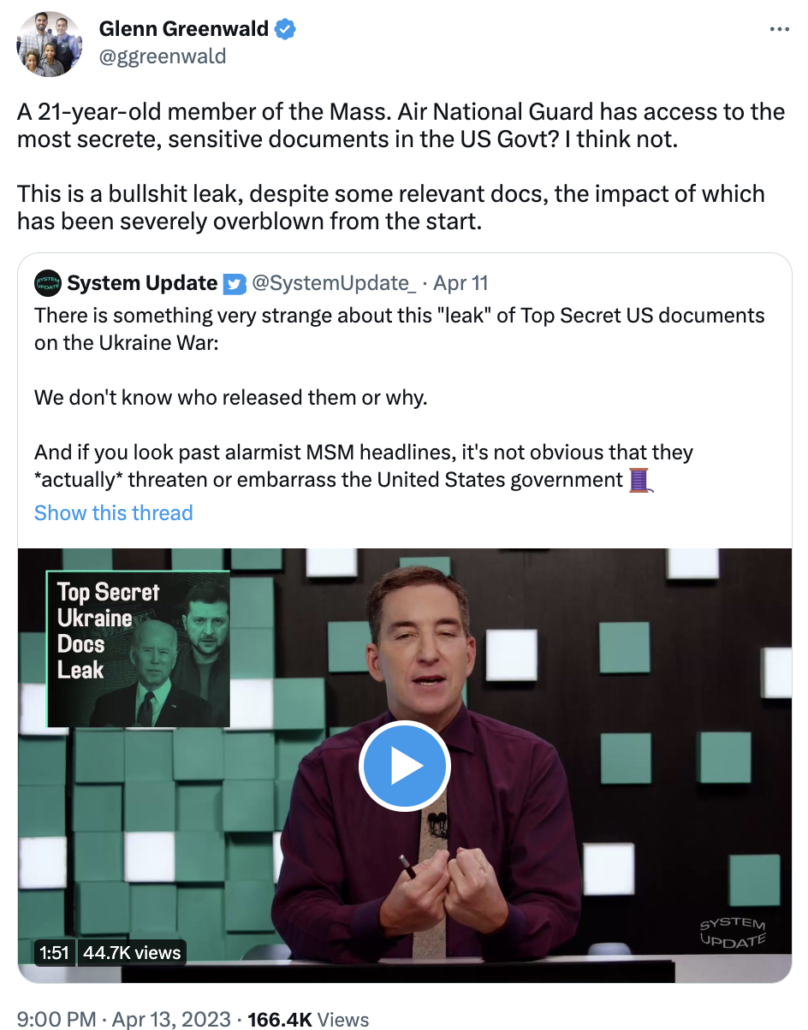

Dan Froomkin says reporters should call Jack Teixeira’s release of highly classified documents “theft,” not a leak, distinguishing “public-spirited” leakers from “self-serving … thieves.” Spencer Ackerman muses that Teixeira, “leaked for that most ineffable thing, something nonmaterial but nevertheless hyper-real in the logic of the poster, and particularly the right-wing-chud poster: clout.” Charlie Savage suggests something distinguishes this case, legally, from those of everyone else (among a limited subset) who took classified information. Glenn Greenwald has been all over the map, in one breath calling this, “a bullshit leak, despite some relevant docs, the impact of which has been severely overblown from the start,” but then applauding Tucker Carlson’s focus on the altered casualty numbers in Ukraine and Tucker’s claims that even Fox has factchecked as an example of, “the significant revelations these leaks provide.”

Now he’s just making shit up about WaPo and NYT hunting down Teixeira, shit that a quick reading of the arrest affidavit readily debunks, shit that ignores that WaPo’s source(s) for hundreds of still-unpublished documents, at least, are one or more of the Discord chat kids, to whom WaPo has given source protection (that will be utterly meaningless in the face of the subpoenas already served).

A bunch of people who made their careers because a young, narcissistic IT guy stole a shit-ton of records about which he had little personal expertise — some incredibly important, a great many useful only to America’s adversaries — seem to be uncertain what to make of Jack Teixeira, who, early reports at least suggest, is an even younger narcissistic IT guy who stole a smaller shit-ton of records about which he had even less personal expertise, some newsworthy, some useful primarily to America’s adversaries.

We will likely have the rest of Teixeira’s young life to get a better understanding of why he allegedly did what he did, which may well be very different than what he told the kids in the Discord chat rooms about why he did what he did, who in any case are entirely unreliable narrators. But then, they may be no more unreliable, as narrators, than Greenwald is about Edward Snowden, and for a similar reason: because their identity is wrapped up in a certain narrative about this dude.

Since this age of the leak dump started, journalists have been sustaining self-serving stories about what leak dumps really are.

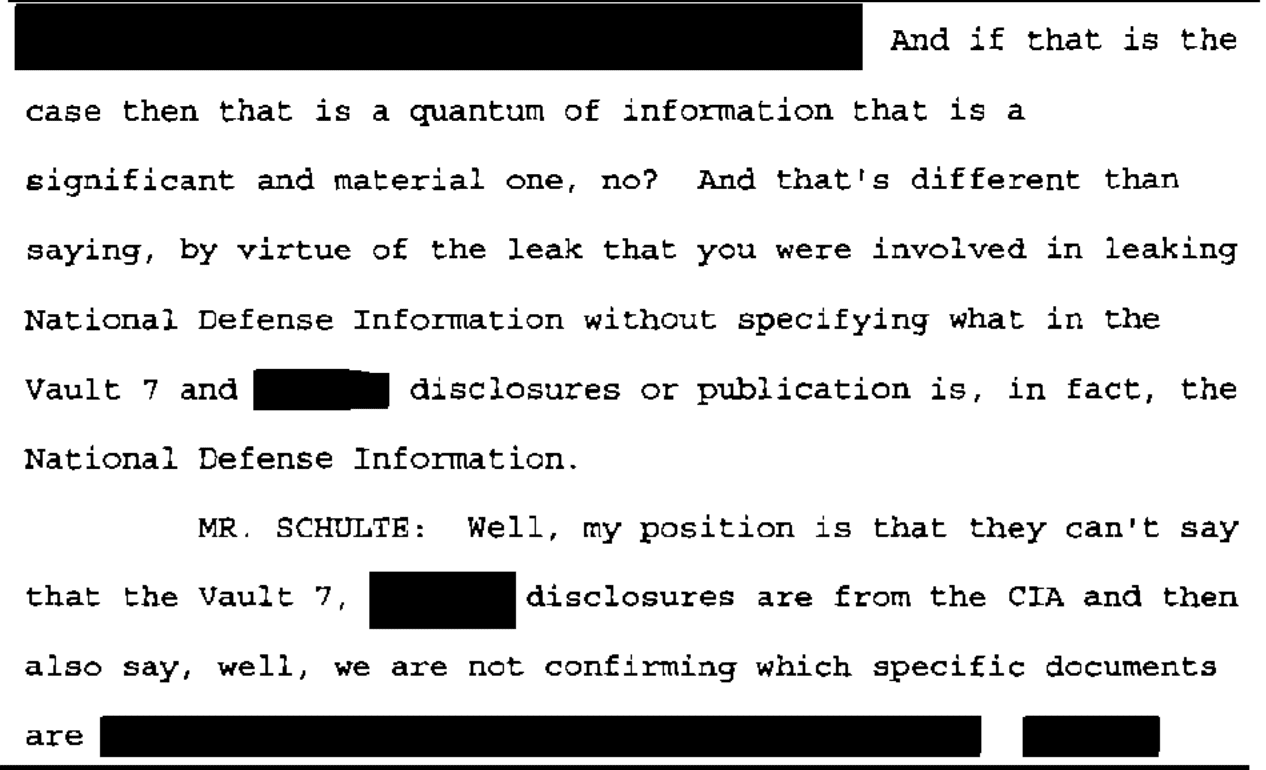

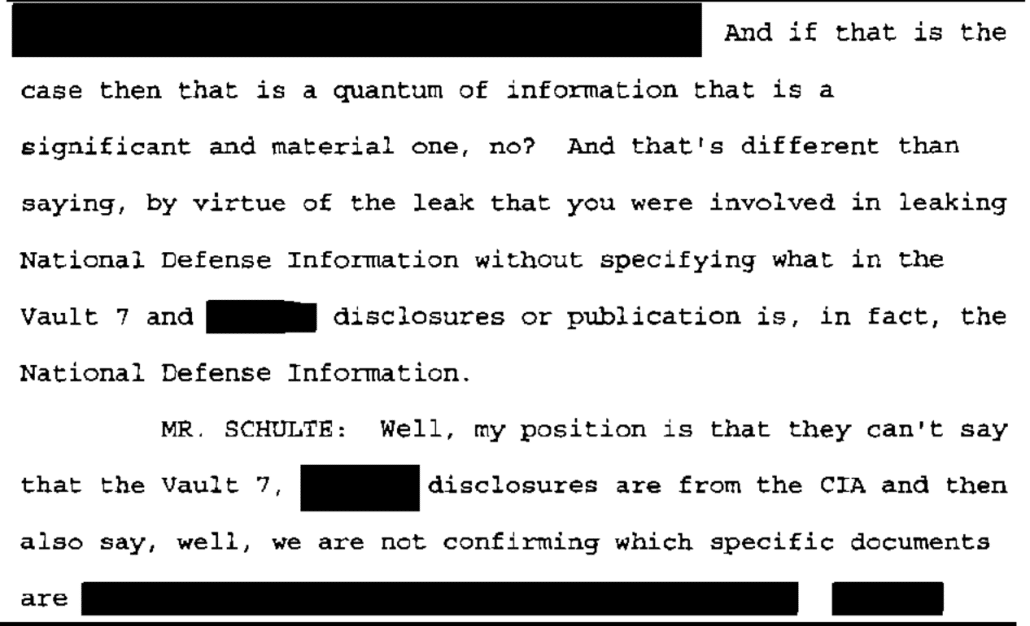

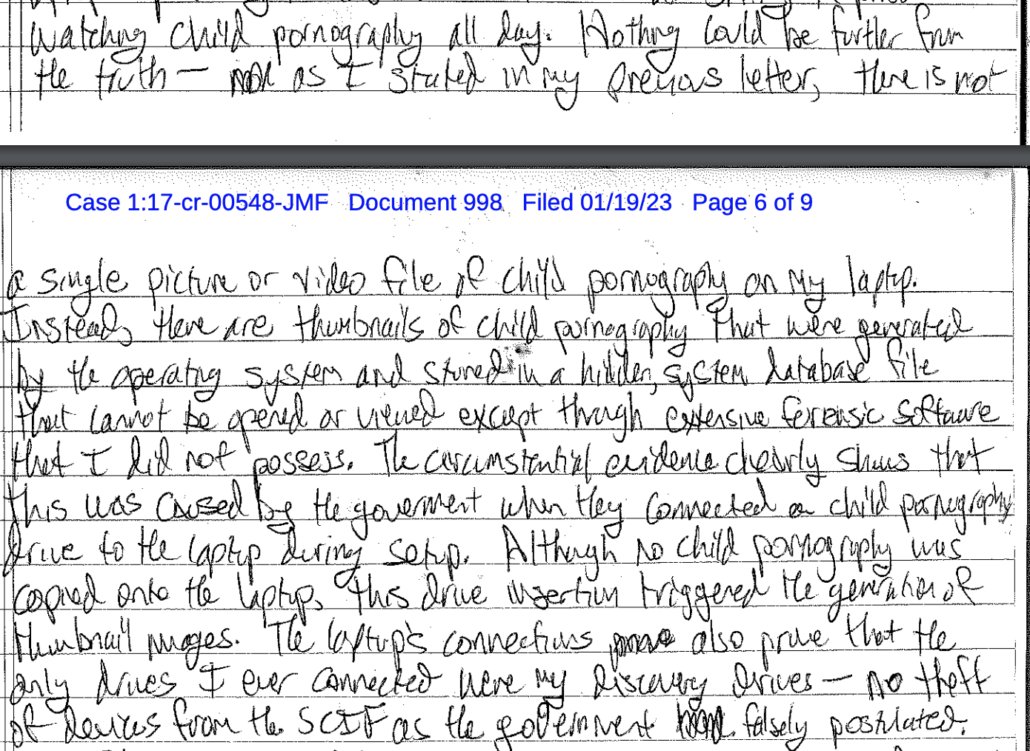

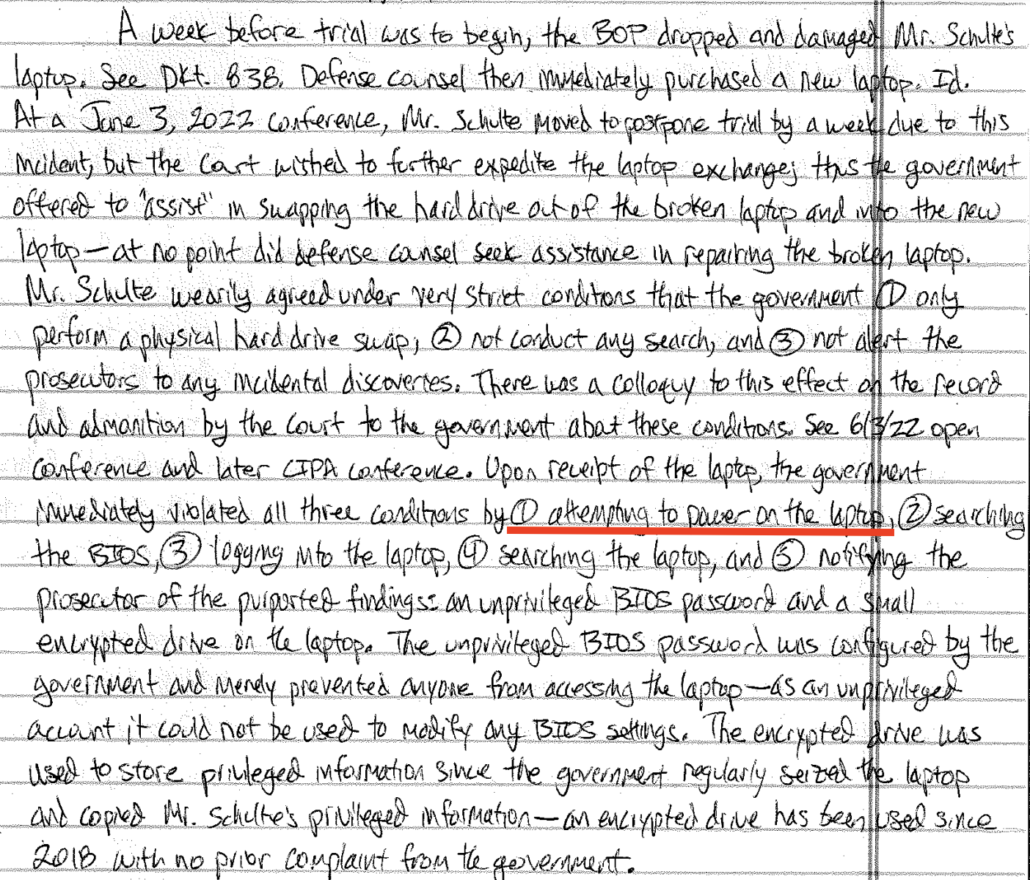

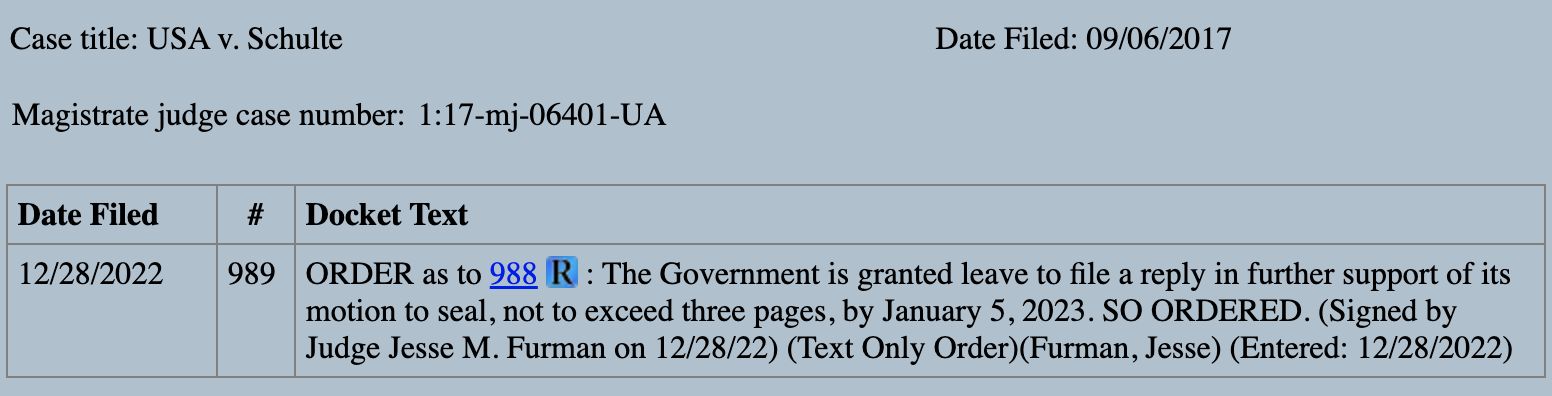

That Ackerman treats Josh Schulte’s hack-and-dump in the same breath as the leak dumps of Chelsea Manning or Edward Snowden, calling Teixeira’s leaks, “something different than the Snowden leaks, Manning leaks or, say, the Vault 7 hack,” is a great example of that. At trial, Schulte didn’t so much claim he was a whistleblower as he was a scapegoat, someone the CIA already hated to blame for an embarrassing compromise. But in his second trial, in the course of representing himself, he performed precisely what the government said he was: a narcissistic coder — KingJosh, he called himself — exacting revenge for the escalating personnel problems he caused after his manager moved his desk. “I think you are playing into the government’s theory of the case,” Judge Jesse Furman warned in a sidebar during Schulte’s cross-examination of a former supervisor, “by making clear to the jury that even today you remain aggrieved by you as being mistreated.”

Vault 7 was not a noble leak. It was an epic act of nihilism. A man-boy retaliating because he couldn’t get his way at work.

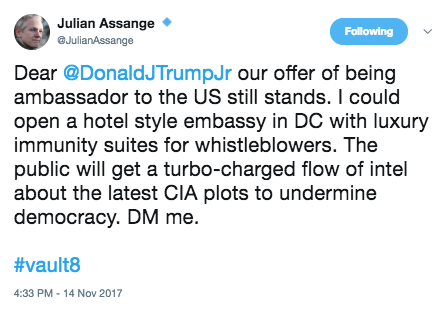

And except for security researchers in the business of attributing CIA hacks, the Vault 7 files weren’t all that newsworthy, either — though they did give Julian Assange a way to pressure the Trump Administration. Plus, the fate of both the Vault 7 files during the nine months between leak and publication, during a period when Assange was a key part of a Russian influence operation, as well as the Vault 8 source code included in Schulte’s guilty verdict, remains unknown. In a letter attempting to exonerate himself (even while exposing the protected identities of several colleagues), Schulte himself described the value that the source code would have for Russia, particularly during that nine month window before the CIA learned Schulte had hacked them:

So much still unknown, and with potential (yet unconfirmed) link between wikileaks and Russia–Did the Russians have all the tools? How long? It seems very unlikely that an intelligence service would ever leak a nation’s “cyber weapons” as the media calls them. These tools are MUCH more valuable undiscovered by the media or the nation that lost them. Now, you can secretly trace and discover every operation that nation is conducting.

I don’t imagine that these issues were what Ackerman had in mind, when comparing Schulte to Manning and Snowden, but perhaps he should give some thought to why he believes otherwise.

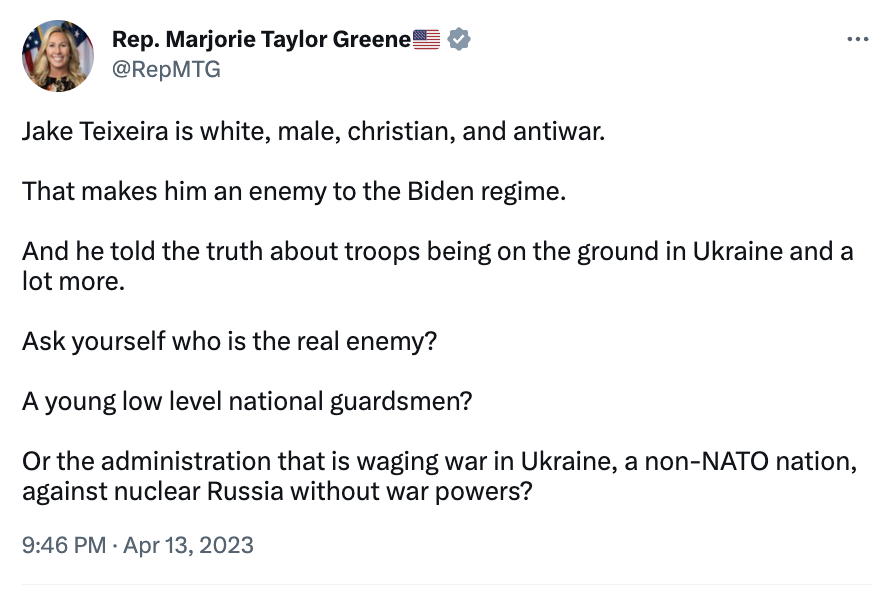

Meanwhile, Marjorie Taylor Greene is already creating a heroic myth about Teixeira not all that dissimilar from the myths WikiLeaks spun about Schulte that Ackerman appears to still believe.

Maybe, like Chelsea Manning, a struggle with his own demons made Teixeira more apt to leverage classified records to win the adulation of a bunch of teenagers. Or maybe, like Schulte, he really is the racist shithole he sounds like.

Or both.

We may never learn how much damage these leaks did such that we could adequately balance their value against their cost. We will undoubtedly get inflammatory claims from prosecutors if Teixeira is ever sentenced, which may or may not be backed by some damage assessment that will get declassified in a decade or three.

Because it’ll be some time before we really understand this guy, because journalists seem to be struggling to understand how to treat him, I thought it worthwhile to lay out some lessons I have learned from covering leak-dumps for 15 years, lessons that have resulted in a radically different view than the Manichean belief in good dumps or bad dumps others have.

Leak dumps don’t care about all that.

In what follows, I’m not questioning the value of (some) of Snowden’s and Manning’s leaks. I’m saying that some of the people most closely involved haven’t taken a step back, in the decade since, to see what we’ve learned since, including some things these celebrated leakers have in common with what we know, so far, of Teixeira.

It’s worth distinguishing leaks from people knowledgable about what they’re leaking

Those who’ve worked on past leak dumps like to compare the leakers with Daniel Ellsberg, a comparison Ellsberg has welcomed.

But for most, there’s something that clearly distinguishes this later group of leakers: many don’t have expertise on the specific files they’re leaking.

Indeed, several of these leakers obtained new jobs while they were already contemplating leaking (or, in Snowden’s case, long after he had started collecting documents to leak). Several took files entirely unrelated to their jobs.

By comparison, Ellsberg was a PhD who leaked the Rand study he worked on himself.

To the extent that prior leak dumpers leaked files they didn’t have specific reason to want to expose, they often did so out of a generalized malaise, usually stemming from America’s war on terror policies. While I think Manning and Daniel Hale’s reaction to the war on terror was just and righteous, and while Teixeira thus far seems like a badly misguided conspiracy theorist, the type of motivation, a general malaise about American conduct, may not be that dissimilar.

Similarly, Teixeira clearly doesn’t have the knowledge or maturity to make an ethical decision to leak these documents. But it’s not clear some of his predecessors did either.

False claims about authentic documents are still false claims

Over the years, Greenwald and others — most recently #MattyDickPics Taibbi — have completely collapsed the distinction between “true” and “authentic.” There’s a good deal of Snowden reporting, for example, that remains uncorrected. Ackerman even repeated one such error, from the Guardian’s report on PRISM, in his 2021 book — “the NSA could conduct what internal documents described as ‘legally-compelled collection’ from the servers—the exact form of access remains unknown”—of PRISM participants. [my emphasis] This description of getting data directly from tech companies’ servers came from a guy who was overselling the program, effectively a Deep State hypester snookering civil libertarian journalists to buy into his hype.

As Bart Gellman described in his own book, not only was the direct access misleading, but it distracted from the more important policy points of the Section 702 collection.

Companies that had declined to comment in advance, or had said nothing of substance, now issued categorical denials that any U.S. agency had “direct access” to their servers. I scrambled to reconcile those statements with the NSA program manager’s explicit words—repeated twice—in the authoritative PRISM overview. Later that night I found a clue in another document from the Snowden archive. There, in a description of a precursor to PRISM, I found a variation on Rick’s formula. “For Internet content selectors, collection managers sent content tasking instructions directly to equipment installed at company-controlled locations,” it said. That sounded as though the U.S. government black box was on company property but might not touch the servers themselves. I updated my story to disclose the conflicting information and the new evidence.

[snip]

The “direct access” question became a big distraction, rightly essential to the companies but not so much to the core questions of public policy.”

The Snowden reporters were under a real time crunch and unbelievable security pressure to report, so have a good excuse, but others don’t.

#MattyDickPics blithely started reporting on Twitter without first bothering to get the least understanding of what he was looking at and he still has never gotten records showing what requests Trump made of Twitter, the only thing close to real censorship in question. Yet because he has some screen caps to wave around, vast swaths of people believe his false claims.

The same is true of the “laptop.” Virtually the entire Republican Party has refused to distinguish between authentic emails on a hard drive allegedly obtained from a Hunter Biden laptop, and the authenticity of the laptop itself, even after people in Rudy’s orbit started altering that hard drive. To say nothing of whether provably authentic emails say what the GOP breathlessly claims they do, which so far, they have not.

As noted, Tucker has already magnified (with Greenwald applauding) two of the false claims about the documents that Teixeira released: the doctored casualty numbers put out by Russia, and misrepresentations about the role of Special Operations forces in Ukraine, which have been debunked by the same Fox News reporter that Tucker tried to get fired one of the previous times she corrected the network’s false claims.

Notably, I think one thing that is contributing to more accurate reporting based on these files is more hesitation from responsible outlets to publish or magnify the files themselves, while still using them as a basis for stories, though as WaPo races to beat its competitors that may be changing.

Documents can serve to distract

And that’s because authentic documents have, from the start of these leak dumps, often served to distract attention from the actual content.

As I noted the other day, FBI’s cooperating troll witness in the Douglass Mackey trial, Microchip, described unashamedly how the trolls ensuring the John Podesta emails would go viral in the last weeks of the 2016 election knew there was no there, there. But they also knew that so long as they could invent some kind of controversy out of them, they could suck the air out of substantive political coverage.

Q What was it about Podesta’s emails that you were sharing?

A That’s a good question.

So Podesta ‘s emails didn’t, in my opinion, have anything in particularly weird or strange about them, but my talent is to make things weird and strange so that there is a controversy. So I would take those emails and spin off other stories about the emails for the sole purpose of disparaging Hillary Clinton.

T[y]ing John Podesta to those emails, coming up with stories that had nothing to do with the emails but, you know, maybe had something to do with conspiracies of the day, and then his reputation would bleed over to Hillary Clinton, and then, because he was working for a campaign, Hillary Clinton would be disparaged.

Q So you’re essentially creating the appearance of some controversy or conspiracy associated with his emails and sharing that far and wide.

A That’s right.

Q Did you believe that what you were tweeting was true?

A No, and I didn’t care.

Q Did you fact- check any of it?

A No.

Q And so what was the ultimate purpose of that? What was your goal?

A To cause as much chaos as possible so that that would bleed over to Hillary Clinton and diminish her chance of winning.

In this model — the exact model adopted by the Twitter Files (and, frankly, virtually all of Trump’s tweets) — the actual documents themselves are just a hook for viral dissemination of the false claims made about the documents, just like most of the Twitter Files are.

Microchip even admitted that disinformation can increase buzz.

Q As you sit here today, back in that time period, did you like to get a rise out of people?

A Sure, yeah.

Q And that’s one of the reasons you posted things on Twitter; correct?

A Correct.

Q Was it your belief back then that disinformation increases buzz? A Um, disinformation sometimes does increase buzz, yes.

The claims about the documents don’t work like truth claims do; instead, they serve to short-circuit rational thought, making it far easier to believe conspiracy theories or intentional disinformation.

We’re seeing some of that now from the disinformation crowd, starting with Tucker and Greenwald.

You can’t always tell who is in a chat room

The Discord kids told WaPo there were “roughly two dozen” active members of the Discord chat room where Teixeira allegedly first released the documents, about half of whom were overseas, including in Ukraine and elsewhere in post-Soviet countries.

Of the roughly 25 active members who had access to the bear-vs-pig channel, about half were located overseas, the member said. The ones who seemed most interested in the classified material claimed to be from mostly “Eastern Bloc and those post-Soviet countries,” he said. “The Ukrainians had interest as well,” which the member chalked up to interest in the war ravaging their homeland.

But the affidavit to search Teixeira’s house says there were twice that many members, approximately 50. WSJ reports that the group was more pro-Russian than the Discord kids have thus far admitted. So while initial reports suggest this was not espionage, it’s far too early to tell either what Teixeira’s motive was or whether he was cultivated by someone else in his server, encouraged to leak certain kinds of documents just as Chelsea Manning was encouraged to seek out certain things over a decade ago.

That’s why I harped on this earlier: I’ve learned, both stuff that’s public and not, about how easily sophisticated actors can manipulate precisely the kinds of people, usually young men, who inhabit these kinds of chat rooms.

Foreign intelligence services have been searching out these opportunities, eliciting both criminal hacking and leaks, for at least a decade.

For example, the LulzSec hackers knew there were Russians in their chat rooms, but didn’t much care. But it might explain why some documents hacked as part of the Syria Leaks that would be particularly damaging to Russia never got published by WikiLeaks, even though multiple sets of the documents were shared with the outlet.

Even the FBI, with subpoena power, may have troubles identifying everyone who participated in a chat room. And if the FBI can’t do it, the teenagers involved likely can’t either. That’s especially true as operational security increases. Which means they may have no idea who they were really talking to, no matter what they tell the WaPo and FBI.

So while Teixeira paid for with this server with his own credit card, it has been shut down long enough that FBI may never be able to figure out who else was in the chat room, much less their real identity. So we may never know what happened before someone decided to ruin their lives by leaking documents with what inevitably will be inadequate operational security.

Which, in the case of Teixeira’s leaks, means we may not know all the people who got advance access to documents months before their publication on Twitter and Telegram alerted the IC about them, to say nothing of whether those people were nudging Teixeira for certain kinds of leaks.

No one controls what happens with dump leaks

Back in 2021, former Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence Sue Gordon and former DOD Chief of Staff Eric Rosenbach seemingly confirmed that the files released by Shadow Brokers in 2016 and 2017 were obtained after two NSA employees, Nghia Pho and Hal Martin, brought them home from work; there’s no evidence that Pho, at least, ever tried to share them and no proof Martin did either.

In two separate incidents, employees of an NSA unit that was then known as the Office of Tailored Access Operations—an outfit that conducts the agency’s most sensitive cybersurveillance operations—removed extremely powerful tools from top-secret NSA networks and, incredibly, took them home. Eventually, the Shadow Brokers—a mysterious hacking group with ties to Russian intelligence services—got their hands on some of the NSA tools and released them on the Internet. As one former TAO employee told The Washington Post, these were “the keys to the kingdom”—digital tools that would “undermine the security of a lot of major government and corporate networks both here and abroad.”

If that’s right, it means the last most damaging leak to DOD wasn’t intentionally leaked at all, which makes it not dissimilar from the way that Teixeira reportedly intended just to share it with the guys in his Discord server. It was exfiltrated from NSA’s secure servers by employees (in Pho’s case, purportedly for work reasons), then stolen, then released.

In the wake of that discovery, DOJ seems to have started pushing to hold leakers accountable for the unintended consequences of their leaks. In a declaration accompanying Terry Albury’s sentencing, for example, Bill Priestap raised the concern that by loading some of the files onto an Internet-accessible computer, Albury could have made them available to entities he had no intention of sharing them with.

The defendant had placed certain of these materials on a personal computing device that connects to the Internet, which creates additional concerns that the information has been or will be transmitted or acquired by individuals or groups not entitled to receive it.

But it’s a lesson journalists don’t take seriously, except (in most cases) their own operational security. What happened to the source code of CIA hacking tools Schulte took? What happened to the damning files on Russia from the Syria leaks? Did Chelsea Manning envision the State cables she leaked would be shared with someone like Israel Shamir, who reportedly shared them, in turn, with Alexander Lukashenko’s regime in advance — the same kind of advance knowledge that Schulte himself reflected on?

Even the laudable, distinguishing aspect of Snowden’s leaks, that he gave them to journalists to determine what was in the public interest (an approach he abandoned when he described CIA infrastructure in his own book), is a double-edged sword. He made multiple copies of his files — most of which weren’t in the public interest — and handed the files to others, including at least one person, Greenwald, that Snowden knew had started out with epically shitty OpSec. We would never know if someone got some the Snowden files as a result unless, like Shadow Brokers or Teixeira’s leaks, someone started sharing them openly on Telegram.

The damage assessment and the reporting goes on

We are nine days into the public part of this leak and, thanks to WaPo reporters’ success at befriending the Discord kids, WaPo has obtained hundreds of otherwise unpublished documents. In addition to about eight background stories on the leaks and charges against Teixeira, WaPo currently has Discord Leak stories on: Taiwan’s military vulnerability, China’s surveillance balloons, Surveillance on Mexican cartels. There’s nothing that makes WaPo’s reporting more or less credible, more or less honorable, because Teixeira released these to show off to his buddies (if that is why he released them).

The Discord Leaks are a leak dump. They may have more in common with past leak dumps than a lot of past leak dump journalists would like to admit. Importantly, no matter what journalists would like to tell themselves, Teixeira’s motive, if he is the source, will have virtually no impact on the damage he does to US national security or the value those documents offer to the public good, both of which will be driven by the content of the documents and the details of any advance notice adversaries may have gotten.

And legally, Teixeira is going to be treated just like Chelsea Manning and Josh Schulte — which is to say, harshly, unless he decides to flip before prosecutors can build charges on another twenty documents and has information of value to prosecutors. That’s not surprising in the least. But — short of proving he knowingly shared these documents with an agent of a foreign power — nor will it be tied to his motive.

Leak dumps don’t care about motive.

Update: PwnAllTheThings’ analysis of the damage caused by the Discord leaks is worth reading. Along with noting that at least one human source has been put in danger by these leaks (as well as a bunch of SIGINT collection), he describes how these releases could have gotten a bunch of Ukrainians killed.

We don’t know yet if Teixeira wanted lots of Ukrainians to die as a result of his leak. But we definitely know he didn’t care if they did, and they certainly had the potential to cause colossal amounts of death—both military and civilian—in Ukraine, even if that huge potential was never fully realized.