Three Things: Pouring Cement Down the Wells

[NB: Check the byline, thanks! /~Rayne]

The last 24 hours made me think of this quote:

Supply chains cannot tolerate even 24 hours of disruption. So if you lose your place in the supply chain because of wild behavior you could lose a lot. It would be like pouring cement down one of your oil wells. — Tom Friedman

I don’t care much for Friedman; he’s a shallow pond. But it’s worth pondering his perspective that supply chains shouldn’t be disrupted.

Tell COVID that, son. Tell Nature’s response to our society’s refusal to stop the supply chain over the last four decades. This mostly-closed system we call Earth has a way of telling us not too subtly when our hubris has gotten out of hand.

Though COVID has been and remains a scourge of human life, it may have been one of the best opportunities to stop the supply chain and literally pour cement down oil wells which in their own way have become a scourge.

Disruption to food and health care supplies has been problematic, but most of that could have been addressed on a proactive basis by government which was both competent and benign. But the bigger problems our society faces, the overarching global climate emergency in particular, may best have been served with pandemic sand in the gears of normalcy.

Finally — there’s no going back to the toxic avoidance of disruption. Change has come whether we like it or not.

~ 3 ~

“Hostile” stakeholders rattled the 12th largest corporation by revenue and the 6th largest oil and gas business this week.

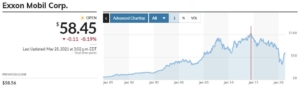

ExxonMobil’s (XOM) board of directors now has at least two new directors promoted by an activist fund, Energy No. 1. The fund, launched by tech industry investor Chris James, had the support of BlackRock, California Public Employees’ Retirement System, California State Teachers’ Retirement System and New York State Common Retirement Fund in its demand to replace at least four of the board with candidates of their choosing. Apart from BlackRock, the three retirement funds are the largest in the U.S. and represent $850 billion in assets; XOM’s valued at $252 billion.

Since late last year, Energy No. 1 has accumulated a $50 million stake in XOM. The fund wants

Engine No. 1 wants ExxonMobil to pledge to reduce its emissions to net zero by 2050, warning that this was “not just a climate issue but a fundamental investor issue — no different than capital allocation or management compensation — given the immense risk to ExxonMobil’s current business model in a rapidly changing world.”

XOM hasn’t performed well over the last 15 years; its last stock price high was in mid-2014 ahead of Iran’s oil re-entering the global market.

XOM has accumulated far too much debt, servicing shareholder dividends, offering weak sauce like investment in carbon capture announced on Earth Day this year, yet still expecting to be part of the White House’s green energy policy.

The corporation doesn’t appear to be making adequate progress toward a low-to-no-oil future, one in which privately-owned vehicles are electric rather than combustion engine. With countries beginning to ban the sale of combustion engine vehicles as soon as 2027 and some cities banning their use as far back as 2013 (ex. Utrecht banned older diesel engines that year), XOM hasn’t made enough effort to move to a different mix of products to maintain or build revenue over the long run.

Nor has the oil and gas corporation responded to climate change as competitors BP and Royal Dutch Shell have by establishing a goal of zero emissions by 2050.

The final tally of shareholder votes and the subsequent board composition may not be known for several weeks. No matter the board’s final members, change isn’t over for XOM, especially when the family which created its progenitor is moving to encourage change. The Rockefellers, heirs to the Standard Oil fortune, provided considerable funds to the #ExxonKnew movement in order to force XOM to deal with its toxic business model.

Don’t be surprised if Rockefellers buy up stock in cement manufacturers.

~ 2 ~

A court told Royal Dutch Shell it must reduce emissions. The 6th largest corporation in the world based on revenue, Shell had been sued by the Dutch branch of the Friends of the Earth for violating human rights with its extractive business, undermining the Paris Agreement.

The suit followed a 2015 precedent in which an environmental activist organization Urgenda had successfully sued the Dutch government for failing to meet its own benchmarks on emissions reduction.

The court ordered Shell to cut the corporation’s net emissions by 45 percent compared to 2019 levels by a 2030 deadline. The emissions to be cut are those generated by Shell’s business processes and not by the use of the fossil fuel products it sells.

A personal experience shapes my opinion about Shell as well as my opinion of the entire fossil fuel industry. In the late 1980s I had been working for a Fortune 100 company which relied on fossil fuels (as many businesses still do today); the corporation had a curriculum of sorts to ensure its workforce was global caliber. The curriculum included a session with a consultancy which guided large corporations in future planning. This consultancy used Royal Dutch Shell’s scenario planning as tool, pointing to Shell’s scenarios which saw peak oil and an end to oil. Shell at that time had already begun future-proofing itself by investing in wind energy development and other alternative energy sources.

But inside a handful of years it was evident the fossil fuel industry didn’t see the same scenarios, and Shell’s management no longer looked presciently oracular. Instead the country watched Enron’s corruption around energy blowing apart any idea the fossil fuel industry was looking deep into the future instead of the next quarter’s profits.

That it takes a court order to force Shell back toward its 1990 direction says something about the fossil fuel industry as well as corporate governance over the the last three decades.

~ 1 ~

The Daily Beast’s headline: Biden Administration Backs Trump’s Massive Alaska Oil Drilling Project

The New York Times’ headline: Biden Administration Defends Huge Alaska Oil Drilling Project

What’s disturbing in these and other outlets’ coverage of ConocoPhillips’ Alaska project is the reference solely to Biden when Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm are surely key to the government’s support for drilling in Alaska. What could these two cabinet-level officials have in common? An inconvenient distaff angle to the prevailing media narrative?

NYT buries at the end of its piece the biggest single reason why the current administration may not yet yank the gangplank out from under ConocoPhillips’ Alaska project:

Other Alaska Native groups, however, said they welcomed the jobs as well as the state and local revenue expected to be generated by the project. In an April letter to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, George Edwardson, president of the Inupiat Community of the Arctic Slope, called oil drilling “critical to the economic survival of the eight Inupiat villages that call this region home” and said the Willow project had the group’s “strong support.”

“Alaska’s oil and gas industry provides much-needed jobs for our people, tax revenue to support our schools and health clinics, and support for basic public services,” he wrote.

If the rest of their livelihood is collapsing under climate change, it’s understandable the local population will grab what jobs they can.

But there’s more to this than jobs for locals as the administration appears to reverse course on fossil fuel development. It’s not jobs but cash injections into local businesses which have suffered under the pandemic; it’s roads and other infrastructure paid for in large part by a corporation and not by local/state/federal tax dollars.

Meanwhile, Joe Biden has been plugging electric vehicles like Ford’s new electric F-150.

Is there a disconnect? Not in my opinion. Instead we are looking at asymmetric warfare, which may also explain why Biden appears to take a less aggressive stance on the Russian NordStream 2 pipeline running beneath the Baltic Sea.

In the case of ConocoPhillips, it’s blowing huge amounts of money to develop a field while vehicle manufacturers are racing toward an all-electric product lineup which may cause the price of oil to drop below cost of production. Unlike its competitors XOM and Shell, ConocoPhillips hasn’t yet had a reckoning with shareholders about its business model though overproduction of oil across the industry has already been a problem during the Trump administration.

Biden pointed out NordStream 2 is already mostly built and paid for — but some of the pipeline’s investors/co-developers are among those pressed by shareholders and environmental activists to reduce their carbon emissions. They’re out the sunk cost into the pipeline if the price of oil drops in response to falling demand.

Ditto for Russia’s oil businesses invested in NordStream 2.

These extractive companies — and petrostates — aren’t going to be able to recoup their investments anywhere near as fast as they’d initially projected. If electric vehicles arrive and are adopted by the public rapidly, they may lose much of their investment.

So go ahead, pump some cash into the economy. Build some roads and maybe some pipeline.

The locals will enjoy them for years to come after the oil business has collapsed and gone.

~ 0 ~

By the way, somebody remind the White House the Trump administration killed participation in tracking products of extractive industries. We still need to keep an eye on them. Specifically, in 2017 the U.S. withdrew from the EITI — Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, the extractive industries anti-corruption effort — and now Congress needs to revisit the Securities and Exchange Commission’s Rule 13q-1, which implemented Section 1504 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform related to tracking large payments made by extractive industries.

Hold this last thought about the U.S. needing to track money related to oil and gas. I promise it’s going to come up in a future post.