DOJ’s Failures to Follow Media Guidelines on the WaPo Seizure

I wanted to add a few data points regarding the report that DOJ subpoenaed records from three WaPo journalists.

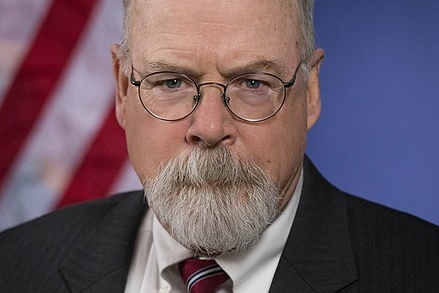

This post is premised on three pieces of well-justified speculation: that John Durham, after having been appointed Special Counsel, obtained these records, that Microsoft challenged a gag, and that Microsoft’s challenge was upheld in some way. I’m doing this post to lay out some questions that others should be asking about what happened.

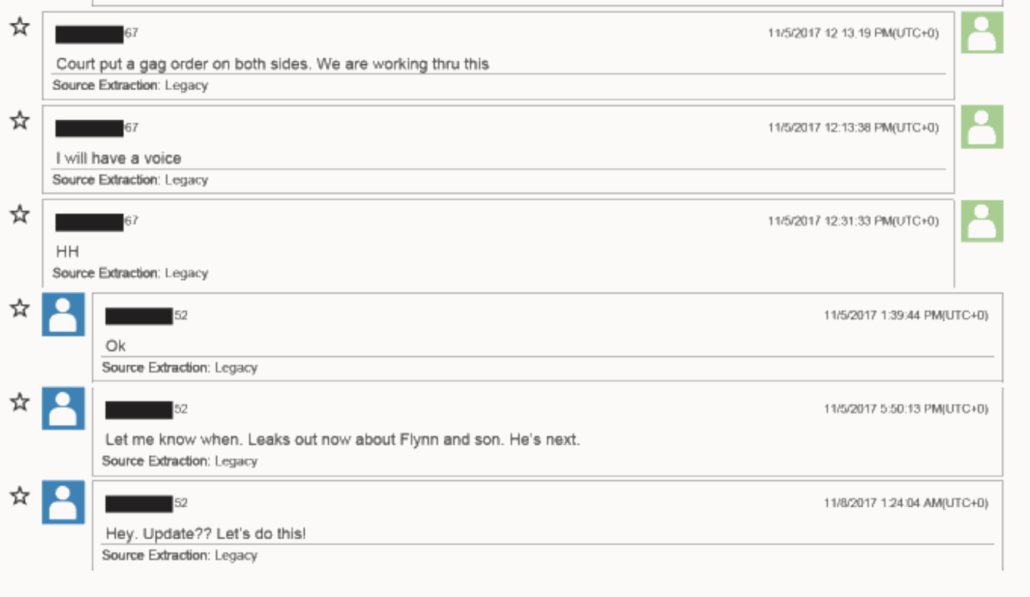

An enterprise host (probably Microsoft) likely challenged a gag order

The report notes that DOJ did obtain the reporters’ phone records, and tried, but did not succeed, in obtaining their email records.

The Trump Justice Department secretly obtained Washington Post journalists’ phone records and tried to obtain their email records over reporting they did in the early months of the Trump administration on Russia’s role in the 2016 election, according to government letters and officials.

In three separate letters dated May 3 and addressed to Post reporters Ellen Nakashima and Greg Miller, and former Post reporter Adam Entous, the Justice Department wrote they were “hereby notified that pursuant to legal process the United States Department of Justice received toll records associated with the following telephone numbers for the period from April 15, 2017 to July 31, 2017.” The letters listed work, home or cellphone numbers covering that three-and-a-half-month period.

[snip]

The letters to the three reporters also noted that prosecutors got a court order to obtain “non content communication records” for the reporters’ work email accounts, but did not obtain such records. The email records sought would have indicated who emailed whom and when, but would not have included the contents of the emails. [my emphasis]

What likely happened is that DOJ tried to obtain a subpoena on Microsoft or Google (almost certainly the former, because the latter doesn’t care about privacy) as the enterprise host for the newspaper’s email service, and someone challenged or refused a request for a gag, which led DOJ to withdraw the request.

There’s important background to this.

Up until October 2017, when the government served a subpoena on a cloud company that hosts records for another, the cloud company was often gagged indefinitely from telling the companies whose email (or files) it hosted. By going to a cloud company, the government was effectively taking away businesses’ ability to challenge subpoenas themselves, which posed a problem for Microsoft’s ability to convince businesses to move everything to their cloud.

That’s actually how Robert Mueller obtained Michael Cohen’s Trump Organization emails — by first preserving, then obtaining them from Microsoft rather than asking Trump Organization (which was, at the same time, withholding the most damning materials when asked for the same materials by Congress). Given what we know about Trump Organization’s incomplete response to Congress, we can be certain that had Mueller gone to Trump Organization, he might never have learned about the Trump Tower Moscow deal.

In October 2017, in conjunction with a lawsuit settlement, Microsoft forced DOJ to adopt a new policy that gave it the right to inform customers when DOJ came to them for emails unless DOJ had a really good reason to prevent Microsoft from telling their enterprise customer.

Today marks another important step in ensuring that people’s privacy rights are protected when they store their personal information in the cloud. In response to concerns that Microsoft raised in a lawsuit we brought against the U.S. government in April 2016, and after months advocating for the United States Department of Justice to change its practices, the Department of Justice (DOJ) today established a new policy to address these issues. This new policy limits the overused practice of requiring providers to stay silent when the government accesses personal data stored in the cloud. It helps ensure that secrecy orders are used only when necessary and for defined periods of time. This is an important step for both privacy and free expression. It is an unequivocal win for our customers, and we’re pleased the DOJ has taken these steps to protect the constitutional rights of all Americans.

Until now, the government routinely sought and obtained orders requiring email providers to not tell our customers when the government takes their personal email or records. Sometimes these orders don’t include a fixed end date, effectively prohibiting us forever from telling our customers that the government has obtained their data.

[snip]

Until today, vague legal standards have allowed the government to get indefinite secrecy orders routinely, regardless of whether they were even based on the specifics of the investigation at hand. That will no longer be true. The binding policy issued today by the Deputy U.S. Attorney General should diminish the number of orders that have a secrecy order attached, end the practice of indefinite secrecy orders, and make sure that every application for a secrecy order is carefully and specifically tailored to the facts in the case.

Rod Rosenstein, then overseeing the Mueller investigation, approved the new policy on October 19, 2017.

The effect was clear. When various entities at DOJ wanted records from Trump Organization after that, DOJ did not approve the equivalent request approved just months earlier.

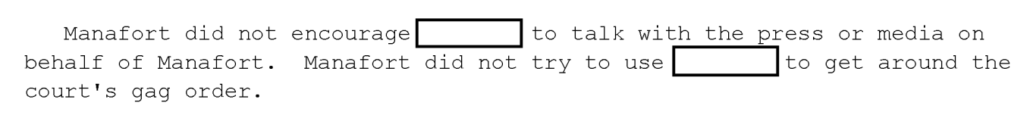

If DOJ withdrew a subpoena rather than have it disclosed, it was probably inconsistent with media guidelines

If I’m right that DOJ asked Microsoft for the reporters’ email records, but then withdrew the request rather than have Microsoft disclose the subpoena to WaPo, then the request itself likely violated DOJ’s media guidelines — at least as they were rewritten in 2015 after a series of similar incidents, including DOJ’s request for the phone records of 20 AP journalists in 2013.

DOJ’s media guidelines require the following:

- Attorney General approval of any subpoena for call or email records

- That the information be essential to the investigation

- DOJ has taken reasonable attempts to obtain the information from alternate sources

Most importantly, DOJ’s media guidelines require notice and negotiation with the affected journalist, unless the Attorney General determines that doing so would “pose a clear and substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation.”

after negotiations with the affected member of the news media have been pursued and appropriate notice to the affected member of the news media has been provided, unless the Attorney General determines that, for compelling reasons, such negotiations or notice would pose a clear and substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation, risk grave harm to national security, or present an imminent risk of death or serious bodily harm.

But a judge can review the justifications for gags before issuing them (for all subpoenas, not just media ones).

Just as an example, the government obtained a gag on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and Google when obtaining Reality Winner’s cloud-based communications a week after they had arrested her (at a time when she was in no position to delete her own content). After a few weeks, Twitter challenged the gag. A judge gave DOJ 180 days to sustain the gag, but in August 2017, DOJ lifted it.

That was a case where DOJ obtained the communications of an accused leaker, with possible unknown co-conspirators, so the gag at least made some sense.

Here, by contrast, the government would have been asking for records from journalists who were not alleged to have committed any crime. The ultimate subject of the investigation would have no ability to destroy WaPo’s records. The records — and the investigation — were over three years old. Whatever justification DOJ gave was likely obviously bullshit.

Hypothetical scenario: DOJ obtains cell phone records only to have a judge rule a gag inappropriate

Let me lay out how this might have worked to show why this might mean DOJ violated the media guidelines. Here’s one possible scenario for what could have happened:

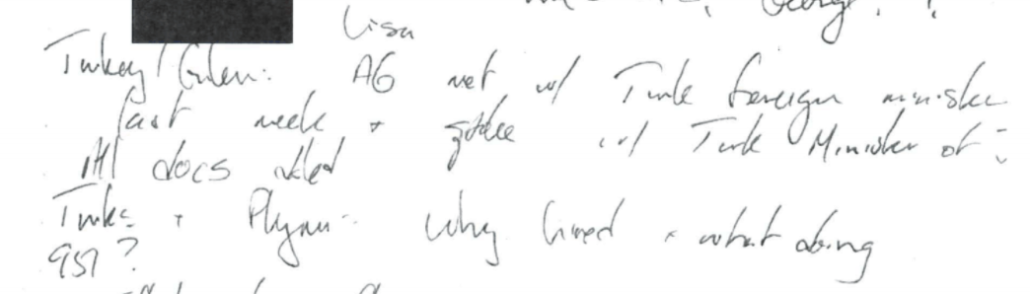

- In the wake of the election, John Durham subpoenaed the WaPo cell providers and Microsoft, asking for a gag

- The cell provider turned over the records with no questions — neither AT&T nor Verizon care about their clients’ privacy

- Microsoft challenged the gag and in response, a judge ruled against DOJ’s gag, meaning Microsoft would have been able to inform WaPo

That would mean that after DOJ, internally — Billy Barr and John Durham, in this speculative scenario — decided that warning journalists would create the same media stink we’re seeing today and make the records request untenable, a judge ruled that that a media stink over an investigation into a 3-year old leak wasn’t a good enough reason for a gag. If this happened, it would mean some judge ruled that Barr and Durham (if Durham is the one who made the request) invented a grave risk to the integrity of their investigation that a judge subsequently found implausible.

It would mean the request itself was dubious, to say nothing of the gag.

Once again, DOJ failed to meet its own notice requirements

And with respect to the gag, this request broke another one of the rules on obtaining records from reporters: that they get notice no later than 90 days after the subpoena. The Justice Manual says this about journalists whose records are seized:

- Except as provided in 28 C.F.R. 50.10(e)(1), when the Attorney General has authorized the use of a subpoena, court order, or warrant to obtain from a third party communications records or business records of a member of the news media, the affected member of the news media shall be given reasonable and timely notice of the Attorney General’s determination before the use of the subpoena, court order, or warrant, unless the Attorney General determines that, for compelling reasons, such notice would pose a clear and substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation, risk grave harm to national security, or present an imminent risk of death or serious bodily harm. 28 C.F.R. 50.10(e)(2). The mere possibility that notice to the affected member of the news media, and potential judicial review, might delay the investigation is not, on its own, a compelling reason to delay notice. Id.

- When the Attorney General has authorized the use of a subpoena, court order, or warrant to obtain communications records or business records of a member of the news media, and the affected member of the news media has not been given notice, pursuant to 28 C.F.R. 50.10(e)(2), of the Attorney General’s determination before the use of the subpoena, court order, or warrant, the United States Attorney or Assistant Attorney General responsible for the matter shall provide to the affected member of the news media notice of the subpoena, court order, or warrant as soon as it is determined that such notice will no longer pose a clear and substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation, risk grave harm to national security, or present an imminent risk of death or serious bodily harm. 28 C.F.R. 50.10(e)(3). In any event, such notice shall occur within 45 days of the government’s receipt of any return made pursuant to the subpoena, court order, or warrant, except that the Attorney General may authorize delay of notice for an additional 45 days if he or she determines that for compelling reasons, such notice would pose a clear and substantial threat to the integrity of the investigation, risk grave harm to national security, or present an imminent risk of death or serious bodily harm. Id. No further delays may be sought beyond the 90‐day period. Id. [emphasis original]

Journalists are supposed to get notice if their records are seized. They’re supposed to get notice no later than 90 days after the records were obtained. AT&T and Verizon would have provided records almost immediately and this happened in 2020, meaning the notice should have come by the end of March. But WaPo didn’t get notice until after Lisa Monaco was confirmed as Deputy Attorney General and, even then, it took several weeks.

DOJ’s silence about an Office of Public Affairs review

While it’s not required by guidelines, in general DOJ has involved the Office of Public Affairs in such matters, so someone who has to deal with the press can tell the Attorney General and the prosecutor that their balance of journalist equities is out of whack. At the time, this would have been Kerri Kupec, who was always instrumental in Billy Barr’s obstruction and politicization.

But it’s not clear whether that happened. I asked Acting Director of OPA Marc Raimondi (the guy who has defended what happened in the press; he was in National Security Division at the time of the request), twice, whether someone from OPA was involved. Both times he ignored my question.

The history of Special Counsels accessing sensitive records and testimony

There’s a history of DOJ obtaining things under Special Counsels they might not have obtained without the Special Counsel:

- Pat Fitzgerald coerced multiple reporters’ testimony, going so far as to jail Judy Miller, in 2004

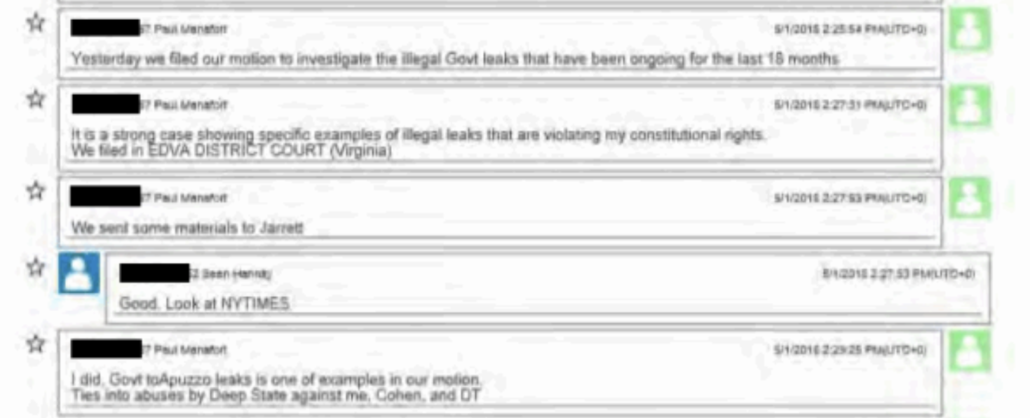

- Robert Mueller obtained Michael Cohen’s records from Microsoft rather than Trump Organization

- This case probably represents John Durham, having been made Special Counsel, obtaining records that DOJ did not obtain in 2017

There’s an irony here: Durham has long sought ways to incriminate Jim Comey, who is represented by Pat Fitzgerald and others. In 2004, as Acting Attorney General, Comey approved the subpoenas for Miller and others. That said, given the time frame on the records request, it is highly unlikely that he’s the target of this request.

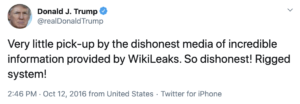

Whoever sought these records, it is virtually certain that the prosecutor only obtained them after making decisions that DOJ chose not to make when these leaks were first investigated in 2017, after Jeff Sessions announced a war on media leaks in the wake of having his hidden meeting with Sergey Kislyak exposed.

That suggests that DOJ decided these records, and the investigation itself, were more important in 2020 than Jeff Sessions had considered them in 2017, when his behavior was probably one of the things disclosed in the leak.

The dubious claim that these records could have been necessary or uniquely valuable

Finally, consider one more detail of DOJ’s decision to obtain these records: their claims, necessary under the media policy, that 3-year old phone and email records were necessary to a leak investigation.

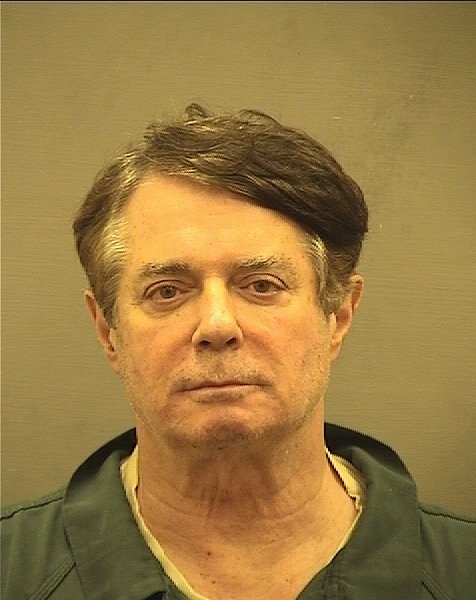

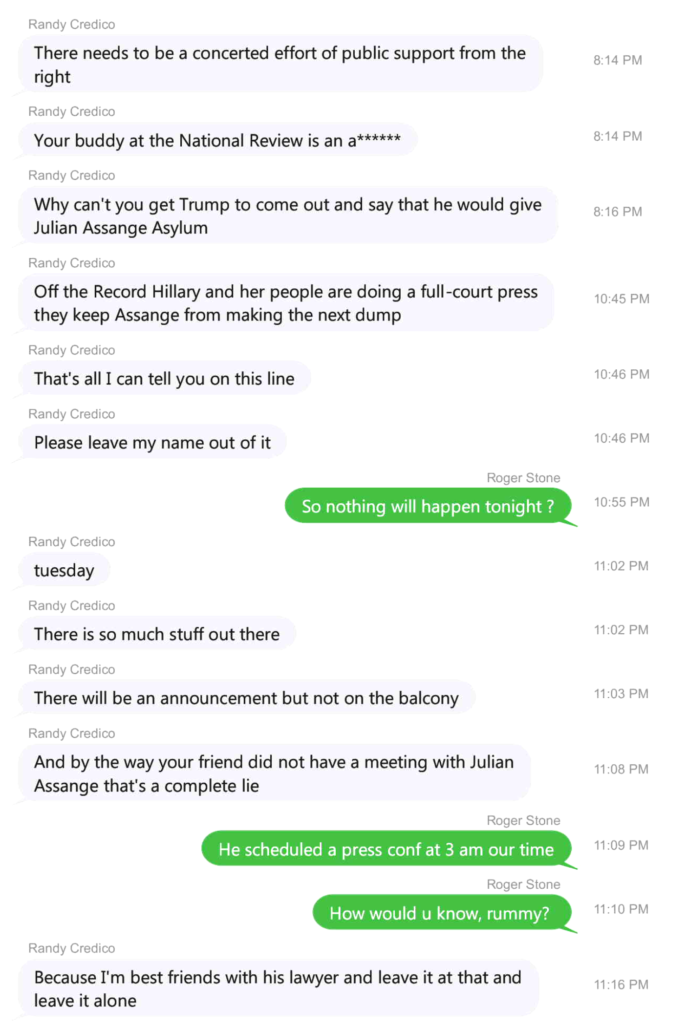

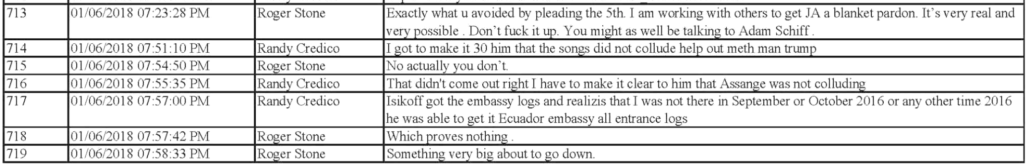

When these leaks were first investigated in 2017, DOJ undoubtedly identified everyone who had access to the Kislyak intercepts and used available means — including reviewing the government call records of the potential sources — to try to find the leakers. If they had a solid lead on someone who might be the leaker, the government would have obtained the person’s private communication records as well, as DOJ did do during the contemporaneous investigation into the leak of the Carter Page FISA warrant that ultimately led to SSCI security official James Wolfe’s prosecution.

Jeff Sessions had literally declared war within days of one of the likely leaks under investigation here, and would approve a long-term records request from Ali Watkins in the Wolfe investigation and a WhatsApp Pen Register implicating Jason Leopold in the Natalie Edwards case. After Bill Barr came in, he approved the use of a Title III wiretap to record calls involving journalists in the Henry Frese case.

For the two and a half years between the time Sessions first declared war on leaks and the time DOJ decided these records were critical to an investigation, DOJ had not previously considered them necessary, even at a time when Sessions was approving pretty aggressive tactics against leaks.

Worse still, DOJ would have had to claim they might be useful. These records, unlike the coerced testimony of Judy Miller, would not have revealed an actual source for the stories. These records, unlike the Michael Cohen records obtained via Microsoft would not be direct evidence of a crime.

All they would be would be leads — a list of all the phone numbers and email addresses these journalists communicated with via WaPo email or telephony calls or texts — for the period in question. It might return records of people (such as Andy McCabe) who could be sources but also had legal authority to communicate with journalists. It would probably return a bunch of records of inquiries the journalists made that were never returned. It would undoubtedly return records of people who were sources for other stories.

But it would return nothing for other means of communication, such as Signal texts or calls.

In other words, the most likely outcome from this request is that it would have a grave impact on the reporting equities of the journalists involved, with no certainty it would help in the investigation (and an equally high likelihood of returning a false positive, someone who was contacted but didn’t return the call).

And if it was Durham who made the request, he would have done so after having chased a series of claims — many of them outright conspiracy theories — around the globe, only to have all of those theories to come up empty. Given that after years of investigation Durham has literally found nothing new, there’s no reason to believe he had any new basis to think he could solve this leak investigation after DOJ had tried but failed in 2017. Likely, what made the difference is that his previous efforts to substantiate something had failed, and Barr needed to empower him to keep looking to placate Trump, and so Durham got to seize WaPo’s records.

Billy Barr has been hiding other legal process against journalists

Given the disclosure that Barr approved a request targeting the WaPo about five months ago and that under Barr DOJ used a Title III wiretap in a leak investigation (albeit targeting the known leaker), it’s worth noting one other piece of oversight that has lapsed under Barr.

In the wake of Jeff Sessions declaring war on leaks in 2017 (and, probably, the leak in question here), Ron Wyden asked Jeff Sessions whether the war on leaks reflected a change in the new media guidelines adopted in 2015.

Wyden asked Sessions to answer the following questions by November 10:

- For each of the past five years, how many times has DOJ used subpoenas, search warrants, national security letters, or any other form of legal process authorized by a court to target members of the news media in the United States and American journalists abroad to seek their (a) communications records, (b) geo-location information, or (c) the content of their communications? Please provide statistics for each form of legal process.

- Has DOJ revised the 2015 regulations, or made any other changes to internal procedures governing investigations of journalists since January 20, 2017? If yes, please provide me with a copy.

In response, DOJ started doing a summary of the use of legal process against journalists for each calendar year. For example, the 2016 report described the legal process used against Malheur propagandist Pete Santilli. The 2017 report shows that, in the year of my substantive interview with FBI, DOJ obtained approval for a voluntary interview with a journalist before the interview because they, “suspected the journalist may have committed an offense in the course of newsgathering activities” (while I have no idea if this is my interview, during the interview, the lead FBI agent also claimed to know the subject of a surveillance-related story I was working on that was unrelated to the subject of the interview, though neither he nor I disclosed what the story was about). The 2017 report also describes obtaining Ali Watkins’ phone records and DOJ’s belated notice to her. The 2018 report describes getting retroactive approval for the arrest of someone for harassing Ryan Zinke but who claimed to be media (I assume that precedent will be important for the many January 6 defendants who claimed to be media).

While I am virtually certain the reports — at least the 2018 one — are not comprehensive, the reports nevertheless are useful guidelines for the kinds of decision DOJ deems reasonable in a given year.

But as far as anyone knows, DOJ stopped issuing them under Barr. Indeed, when I asked Raimondi about them, he didn’t know they existed (he is checking if they were issued for 2019 and 2020).

So we don’t know what other investigative tactics Barr approved as Attorney General, even though we should.