As noted yesterday, Judge Aileen Cannon enjoined the government from conducting a criminal investigation into violations of the Espionage Act and obstruction because around 4.5% — possibly as little as .5% — of the materials seized from Trump in 27 boxes amount to things more personal than MAGA hats and press clippings.

Her logic rests on a series of false claims about what amounts to being owned.

To understand why, you need to understand how a conservative Republican judge — child of a refugee from Communist Cuba! — upended property rights to halt a criminal investigation into the theft of property.

Aileen Cannon agrees that possession is the law

Trump’s motion had asked for a Special Master who would tell them what was in the boxes that Evan Corcoran told the FBI he had already reviewed diligently so he, Trump, could file a Rule 41(g) motion to claw that stuff back. He wasn’t filing it as a Rule 41(g) motion. He was filing something to give the lawyer who claimed to have gone through all these boxes enough knowledge of them to file a Rule 41(g) motion.

But, as DOJ’s head of the Espionage section. Jay Bratt, explained when he described in a hearing before Judge Cannon that DOJ was treating this as a Rule 41(g) motion and why this should end everything, Rule 41(g) only works if someone is trying to claw back their own property. Trump doesn’t own the vast majority of what was seized.

One is Rule 41(g), and we believe this is a truly 41(g) motion; or second, the Court can exercise a second or anomalous jurisdiction. To do that, that then triggers certain inquires the Court must make, and it also triggers certain burdens on them to establish that they satisfy those standards.

The civil cover sheet to this matter references Rule 41(g). There are frequent references throughout Plaintiff’s briefs to Rule 41(g), and we believe that what they have really done is brought a Rule 41(g) motion. And if the Court interprets and reads and applies Rule 41(g) strictly, they cannot get a special master or the relief that they seek, and that’s because the key factor that must exist for a party to bring a Rule 41(g) motion is that the party has a possessory interest in the property at issue.

And let me describe what the former President has as Presidential records that the 45th President took. He is no longer the President; and because he is no longer the President, he did not have the right to take those documents. He was unlawfully in possession of them; and because he has no possessory interest in those records, that ends the analysis under Rule 41(g).

That means, under the second prong of binding precedent in the 11 Circuit, if Trump doesn’t own this stuff, he’s not entitled to relief.

THE COURT: You don’t dispute one can bring a civil action in equity for the return of property pre-indictment assuming the equitable factors and consideration to counsel in favor of such an action.

MR. BRATT: I do agree with that; but under the Richey factors and to go through them — and actually, I was going to start with the first, callus disregard for Plaintiff’s constitutional rights, I will get back to that. But the second Richey factor is that Plaintiff must have an interest in and need for the property, and this plaintiff does not have an interest in the classified and other Presidential records. So under Richey, that, in and of itself, defeats or should point the Court to decline to exercise its equitable jurisdiction.

Cannon agreed with Bratt on the law. If Trump doesn’t own this stuff, he can’t demand it back.

Like Bratt, she sort of takes Trump’s bizarre filing as a Rule 41(g) motion too, even while she calls Trump’s arguments convoluted.

As previewed, Plaintiff initiated this action with a hybrid motion that seeks independent review of the property seized from his residence on August 8, 2022, a temporary injunction on any further review by the Government in the meantime, and ultimately the return of the seized property under Rule 41(g) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. 6 Though somewhat convoluted, this filing is procedurally permissible7 and creates an action in equity. See Richey v. Smith, 515 F.2d 1239, 1245 (5th Cir. 1975) (“[A] motion [for return of property] prior to [a] criminal proceeding[] . . . is more properly considered simply a suit in equity rather than one under the Rules of Criminal Procedure.”);

By treating this as a convoluted Rule 41(g) motion, she is conceding the centrality of the ownership of the items at issue to the analysis.

Indeed, as she notes in a footnote, this is all about property.

7 Rule 41(g) allows movants, prior to the return of an indictment, to initiate stand-alone actions “in the district where [their] property was seized.” See Fed. R. Crim. P. 41(g); United States v. Wilson, 540 F.2d 1100, 1104 (D.C. Cir. 1976) (“Property which is seized . . . either by search warrant or subpoena may be ultimately disposed of by the court in that proceeding or in a subsequent civil action.”); In the Matter of John Bennett, No. 12-61499-CIV-RSR, ECF No. 1 (S.D. Fla. July 31, 2012) (initiating an action with a “petition to return property”); see also In re Grand Jury Investigation of Hugle, 754 F.2d 863, 865 (9th Cir. 1985) (“[A] court is not required to defer relief [relating to privileged material] until after issuance of the indictment.”).

So Judge Cannon agrees that this issue significantly pivots around property. It is in how she effectively seizes government property (in the same ruling where she suggests one should be able to steal and sell Ashely Biden’s property with impunity) where things begin to go haywire.

Aileen Cannon refused to return Trump’s personal information so she could justify stealing US taxpayer property

Cannon starts her decision on whether to appoint a Special Master not on the privilege questions, but on Richey, which is how one decides whether someone should get their property back. In her analysis of the second prong of Richey, she decides (virtually all of this entails Cannon doing things Trump’s attorneys did not do) that Trump does have a property interest in this material. She points to medical and tax records the likes of which she believes people should be able to steal from Ashely Biden with impunity and says those — a tiny fraction of the whole — gives Trump standing under Richey.

The second factor—whether the movant has an individual interest in and need for the seized property—weighs in favor of entertaining Plaintiff’s requests. According to the Privilege Review Team’s Report, the seized materials include medical documents, correspondence related to taxes, and accounting information [ECF No. 40-2; see also ECF No. 48 p. 18 (conceding that Plaintiff “may have a property interest in his personal effects”)]. The Government also has acknowledged that it seized some “[p]ersonal effects without evidentiary value” and, by its own estimation, upwards of 500 pages of material potentially subject to attorney-client privilege [ECF No. 48 p. 16; ECF No. 40 p. 2]. Thus, based on the volume and nature of the seized material, the Court is satisfied that Plaintiff has an interest in and need for at least a portion of it, even if the underlying subsidiary detail as to each item cannot reasonably be determined at this time based on the information provided by the Government to date. 10

10 To the extent the Government challenges Plaintiff’s standing to bring this action, the Court addresses that argument below. See infra Discussion II.

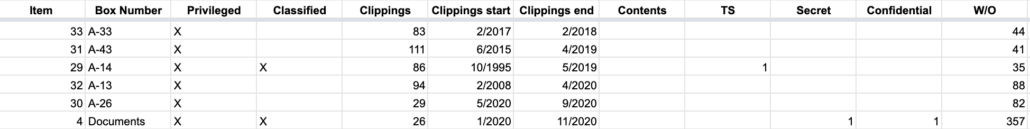

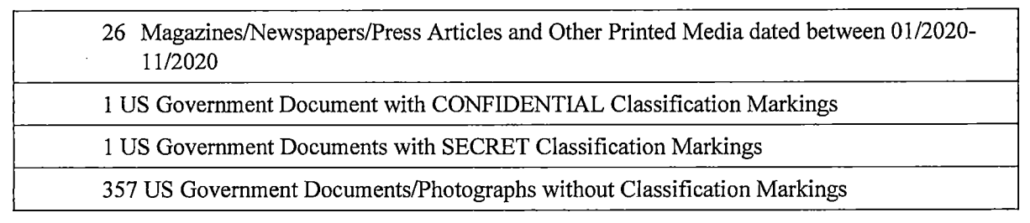

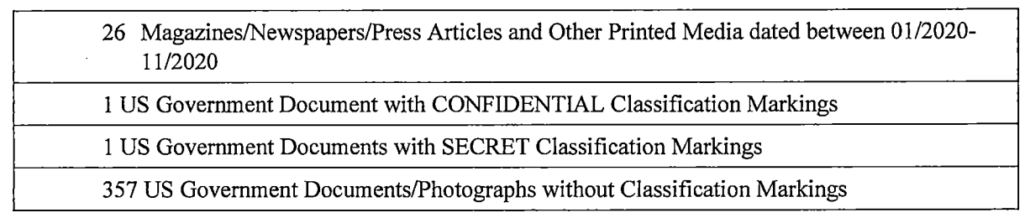

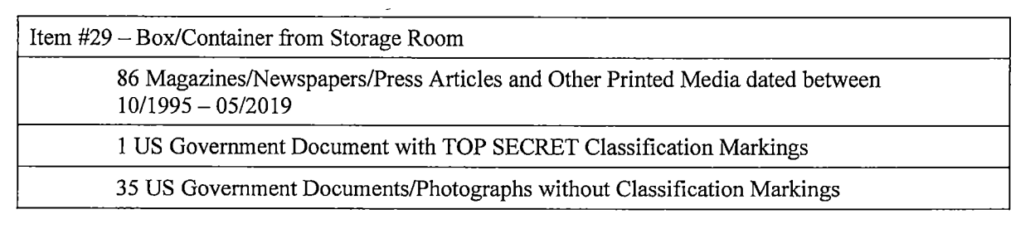

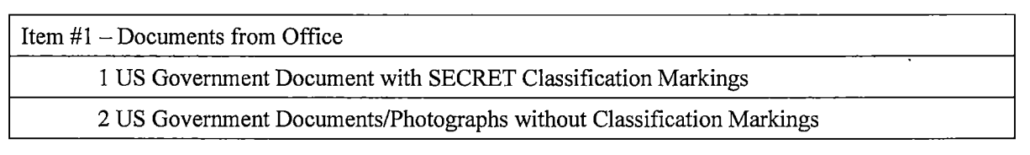

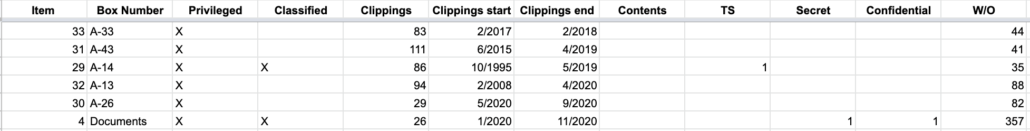

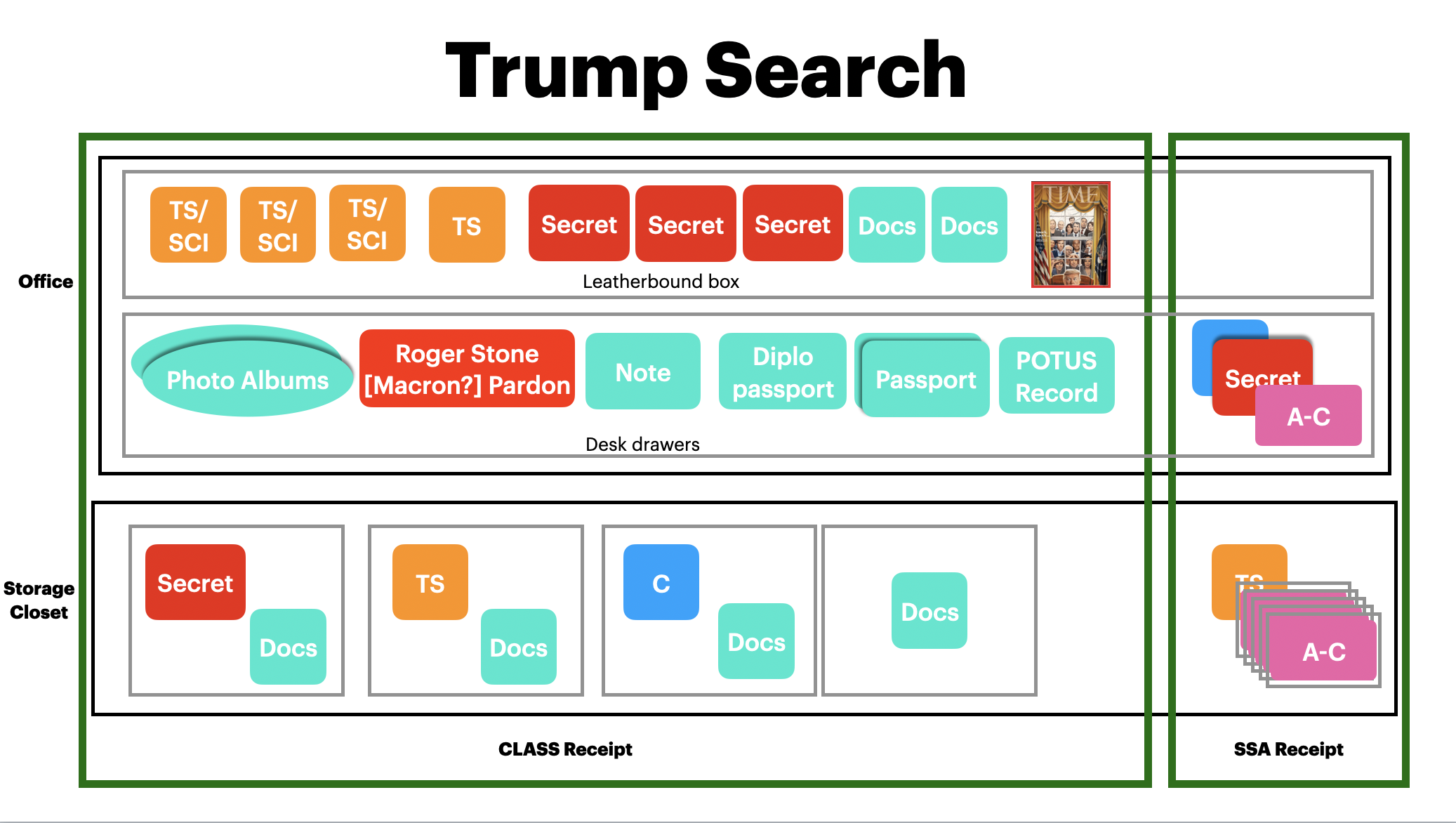

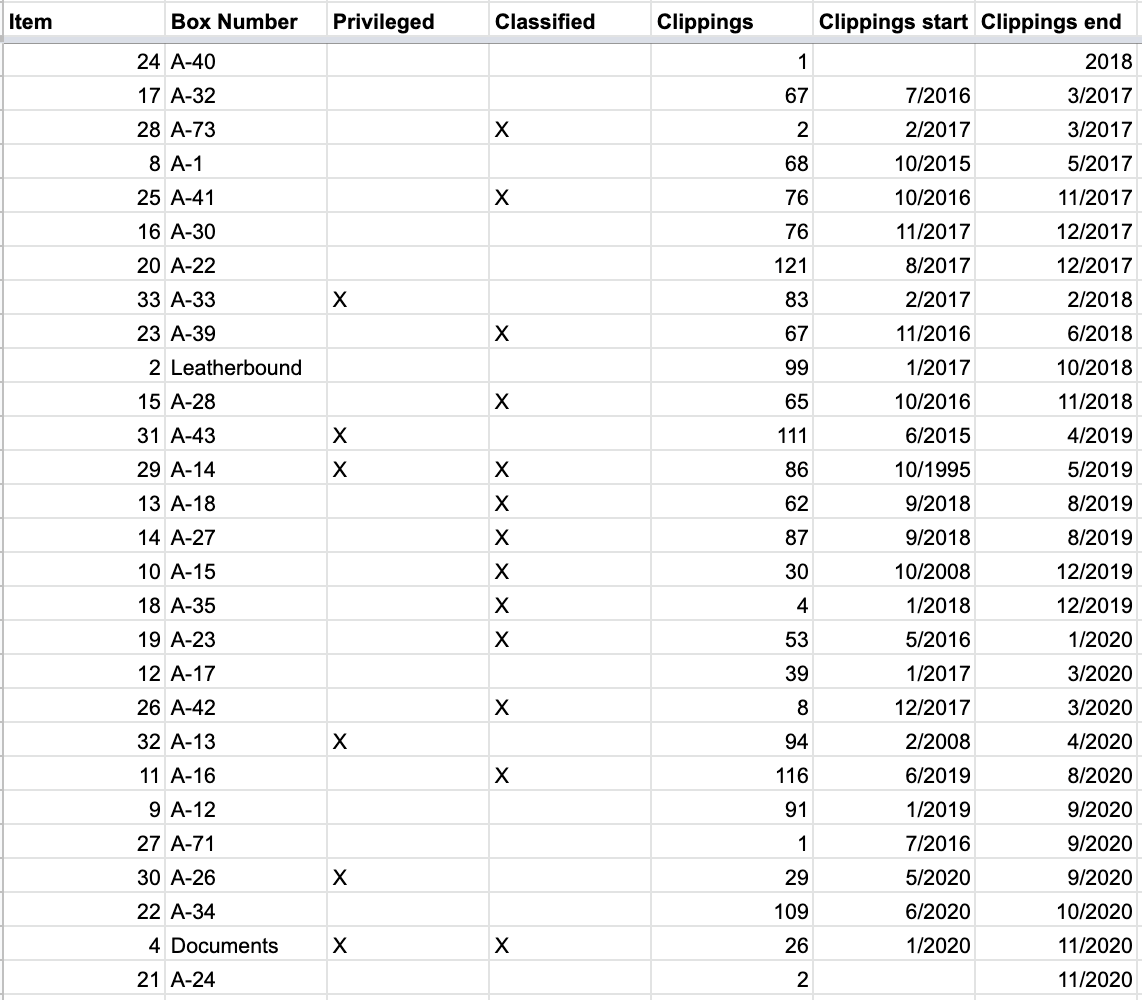

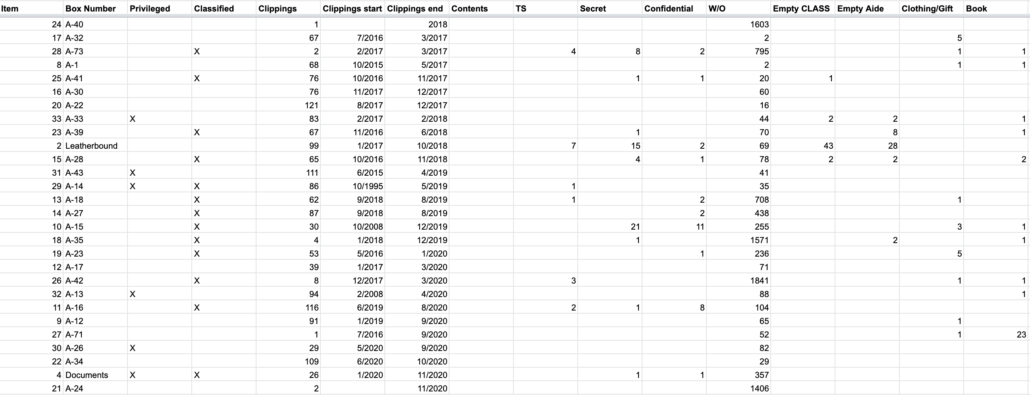

This is why I laid out how small a percentage of the seized records this involves. On August 8, the government seized 11,282 stolen government records, of which 103 are marked as classified, 1,673 press clippings, and around 64 “sets of material” that might be privileged.

Those 64 sets of material have not been shared with the investigative team. They’ve been segregated by the privilege team. Cannon doesn’t even claim Trump owns them. He may not! They may be White House Counsel documents about the Mazars challenge or White House physician documents about Trump’s COVID treatment. We don’t know whether they do or not because they are being protected, for Trump’s sake.

But the claim that this personal information equates to a property interest is one of three things that Cannon cites to substantiate her claim that something among this vast swath of stolen documents is owned by Donald Trump.

Then, Aileen Cannon double counts stuff. She only knows about — and has “leaked” the details about these medical and tax records — because she (unlike the investigative team) has read and publicly disclosed material from the filter team report. There are upwards of 500 pages that might be privileged (520, the privilege team says), which she counts as a separate property interest of Trump’s from the seized medical and tax records found within those 520 pages that only the privilege team has seen, even though it’s the same 520 pages and US taxpayers might well own those 520 pages (if, for example, they pertained to Trump’s treatment for COVID or DOJ’s defense of Trump in the Mazars case) as well.

That would be crazy enough. But to ensure she’d even get to this ruling, Cannon already refused to let DOJ share all this, the 520 pages of potentially privileged material and the tax and medical records therein. The filter team lawyers, Benjamin Hawk, asked to do so last Thursday. But Cannon told him no, because she wanted to do all this “holistically”.

MR. HAWK: We would like to seek permission to provide copies — the proposal that we offered, Your Honor, provide copies to counsel of the 64 sets of the materials that are Bates stamped so they have the opportunity to start reviewing.

THE COURT: I’m sorry, say that again, please.

MR. HAWK: The privilege review team would have provided Bates stamped copies of the 64 sets of documents to Plaintiff’s counsel. We would like to seek permission from Your Honor to be able to provide those now, not at this exact moment but to move forward to providing those so counsel has the opportunity to review them and understand and have the time to review and do their own analysis of those documents to come to their own conclusions. And if the filter process without a special master were allowed to proceed, we would engage with counsel and have conversations, determine if we can reach agreements; to the extent we couldn’t reach agreements, we would bring those before the Court, whether Your Honor or Judge Reinhart. But simply now, I’m seeking permission just to provide those documents to Plaintiff’s counsel.

THE COURT: All right. I’m going to reserve ruling on that request. I prefer to consider it holistically in the assessment of whether a special master is indeed appropriate for those privileged reviews.

So the only reason DOJ still has exclusive possession of the materials on which she hangs her Richey analysis is because she, Aileen Cannon, prohibited DOJ from sharing it, and she uses DOJ’s possession of it to prevent the government from investigating the thousands of government documents Trump stole.

As for the rest, she makes stuff up. As noted, she claims that in the government’s response they admitted that, “The Government also has acknowledged that it seized some “[p]ersonal effects without evidentiary value.” She returns to this citation several times to claim that the government has acknowledged it seized stuff it should not have. Tell me if you can find that acknowledgment in the passage she cites (I’ve bolded what she claims is such an acknowledgement and italicized something Cannon entirely ignored):

As his last claim for relief, Plaintiff asks this Court to order “the Government to return any item seized pursuant to the Search Warrant that was not within the scope of the Search Warrant.” D.E. 28 at 10; see id. at 4. In Plaintiff’s view, retaining such material “would amount to a violation of the Fourth Amendment’s protections against wrongful searches and seizures.” D.E. 28 at 9. Although Plaintiff does not specify what material he contends was seized in excess of the search warrant, certain personal effects were commingled with classified material in the Seized Evidence, and they remain in the custody of the United States because of their evidentiary value. Personal effects without evidentiary value will be returned.

Nonetheless, contrary to Plaintiff’s contention, personal effects in these circumstances are not subject to return under Criminal Rule 41(g), for four independent reasons. First, the search warrant authorized seizing and retaining items in containers/boxes in which documents with classification markings were stored. See MJ Docket D.E. 17 at 4. Evidence of commingling personal effects with documents bearing classification markings is relevant evidence of the statutory offenses under investigation.

Second, even if the personal effects were outside the scope of the search warrant (contrary to fact), their seizure and retention would not violate the Fourth Amendment because they were commingled with documents bearing classification markings that were indisputably within the scope of the search warrant. See, e.g., United States v. Wuagneux, 683 F.2d 1343, 1353 (11th Cir. 1982) (“It was also reasonable for the agents to remove intact files, books and folders when a particular document within the file was identified as falling with the scope of the warrant. To require otherwise ‘would substantially increase the time required to conduct the search, thereby aggravating the intrusiveness of the search.’” (citation omitted)).

Third, even if the personal effects were seized in excess of the search warrant—which Plaintiff has not established—Criminal Rule 41(g) does not require their return because that Rule was amended in 1989 to recognize that the United States may retain evidence collected while executing a warrant in good faith. See, e.g., Grimes v. CIR, 82 F.3d 286, 291 (9th Cir. 1996). As the Advisory Committee explained in connection with the 1989 amendment of Criminal Rule 41(e) (now subsection (g)), Supreme Court precedent permits “evidence seized in violation of the fourth amendment, but in good faith pursuant to a warrant,” to be used “even against a person aggrieved by the constitutional violation,” and “Rule 41(e) is not intended to deny the United States the use of evidence permitted by the fourth amendment and federal statutes.” The decoupling of Criminal Rule 41(g) from the Fourth Amendment also explains why a motion to return property provides no forum to litigate the scope of a search warrant: failure to comply with a search warrant or the Fourth Amendment is neither necessary nor sufficient to prove a movant’s entitlement to the return of property under Criminal Rule 41(g). [bold and italics mine]

Look at what she did!!! First, she took a subjunctive statement — that if the FBI were to find personal items without evidentiary value (like his passports, which they already returned, of which she makes no mention, because it would prove the government is right) — and outright lied and claimed it was a concession they had found such things. The reason she doesn’t mention the passports, by the way, is because the government said, “The location of the passports is relevant evidence in an investigation of unauthorized retention and mishandling of national defense information.” So even there, they asserted an investigative interest. But in a passage where the government states, outright, that the Plaintiff has not established the government has seized anything not covered by the warrant, Aileen Cannon simply invents a concession that says they took stuff that is unnecessary to the investigation. Makes it up!

And yet she uses it as part of her “proof” that there are personal belongings among the 11,000 stolen documents. And she invented it out of thin air.

Cannon puts a Special Master where the DC District should be

Note what Judge Cannon didn’t deal with in this analysis of the second prong of Richey? DOJ’s assertion that Trump doesn’t own any of the 11,000-plus stolen documents seized as contraband. She separates the question of who owns the bulk of the materials seized into a separate section, purportedly about standing, not Richey.

Only after she decides that Trump has a possessory interest in the 11,000 stolen documents because of the tax and medical records therein that she prevented DOJ from sharing with Trump’s lawyers last week does she turn to the Presidential Records Act that makes these stolen documents. The first time she does so, and in a separate section, she dismisses the government’s argument about standing under Richey — analysis about which she has just done — as premature.

The Government relies on the definition of “Presidential records” under the Presidential Records Act (the “PRA”), see 44 U.S.C. § 2201(2), and on the Eleventh Circuit’s decision in Howell, 425 F.3d at 974; see supra note 12.

Plaintiff opposes the Government’s standing argument as premature and fundamentally flawed [ECF No. 58 p. 2]. In Plaintiff’s view, what matters now is his authority to seek the appointment of a special master—not his underlying legal entitlement to possess the records or his definable “possessory interest” under Rule 41(g) [ECF No. 58 pp. 4–6]. Moreover, Plaintiff adds, even assuming the Court were inclined at this juncture to consider Plaintiff’s potential claim of unreasonableness under the Fourth Amendment, settled law permits him, as the owner of the premises searched, to object to the seizure as unreasonable [ECF No. 58 pp. 2, 4–6].

Having considered these crisscrossing arguments, the Court concludes that Plaintiff is not barred as a matter of standing from bringing this Rule 41(g) action or from invoking the Court’s authority to appoint a special master more generally.

[snip]

Although the Government argues that Plaintiff has no property interest in any of the presidential records seized from his residence, that position calls for an ultimate judgment on the merits as to those documents and their designations. [my emphasis]

Side note: it doesn’t matter for Fourth Amendment precedent, but this is another example of where Cannon seizes and reallocates property with wild abandon. Trump does not own Mar-a-Lago. The club does, and Trump Organization owns that. The failson is apparently in charge of it all. This has apparently been an issue in both the Beryl Howell grand jury docket and the Bruce Reinhart warrant docket. So while it doesn’t matter to her legal analysis, she simply invents Trump’s ownership of a club that his biological person does not own and on that basis uses it to give Trump standing.

But in this passage, which she conducts separately from the Richey analysis that pivots entirely on a made up claim and possession of documents she herself prohibited the government from sharing, she implies that proceedings before her will make, “an ultimate judgment on the merits as to those documents and their designations” — that is, a determination of ownership under the PRA.

Five pages later, in a section on Executive Privilege, she concedes that questions about ownership under the Presidential Records Act don’t belong before a Special Master appointed by a SDFL judge. It belongs in the DC District.

16 The Court recognizes that, under the PRA, “[t]he United States District Court for the District of Columbia shall have jurisdiction over any action initiated by the former President asserting that a determination made by the Archivist” to permit public dissemination of presidential records “violates the former President’s [constitutional] rights or privileges.” 44 U.S.C. § 2204.

Having conceded that, Cannon has conceded she has no authority to appoint a Special Master to adjudge ownership under PRA. But in the same opinion where she concedes she doesn’t have this authority, she appoints a Special Master to weigh in on the matter.

This wouldn’t matter if Cannon just appointed a Special Master to review the attorney-client privilege claims. But her order envisions a review of all 11,000 seized stolen documents, based on her assertion that the question of ownership is still uncertain.

Aileen Cannon declares herself President and overrides Joe Biden’s delegated Executive Privilege decision

Judge Cannon could have simply appointed a Special Master to review Attorney-Client determinations (and such a decision might have been modest and defensible). But after assuming the right to appoint a Special Master to determine PRA issues, she then wades into Executive Privilege, claiming that Trump (whose lawyer told the FBI he had closely inspected all these boxes) has not had an opportunity to invoke Executive Privilege.

On the current record, having been denied an opportunity to inspect the seized documents, Plaintiff has not formally asserted executive privilege as to any specific materials, nor has the incumbent President upheld or withdrawn such an assertion.

She points to two precedents pertaining to the EP claims of a former President against a co-equal branch of government and on that basis claims that it remains unsettled whether Trump can invoke Executive Privilege to claw back material from the Executive branch.

The Government asserts that executive privilege has no role to play here because Plaintiff—a former head of the Executive Branch—is entirely foreclosed from successfully asserting executive privilege against the current Executive Branch [ECF No. 48 pp. 24–25]. In the Court’s estimation, this position arguably overstates the law. In Nixon v. Administrator of General Services, 433 U.S. 425 (1977), a case involving review of presidential communications by a government archivist, the Supreme Court expressly recognized that (1) former Presidents may assert claims of executive privilege, id. at 439; (2) “[t]he expectation of the confidentiality of executive communications . . . [is] subject to erosion over time after an administration leaves office,” id. at 451; and (3) the incumbent President is “in the best position to assess the present and future needs of the Executive Branch” for purposes of executive privilege, id. at 449. The Supreme Court did not rule out the possibility of a former President overcoming an incumbent President on executive privilege matters. Further, just this year, the Supreme Court noted that, at least in connection with a congressional investigation, “[t]he questions whether and in what circumstances a former President may obtain a court order preventing disclosure of privileged records from his tenure in office, in the face of a determination by the incumbent President to waive the privilege, are unprecedented and raise serious and substantial concerns.” Trump v. Thompson, 142 S. Ct. 680, 680 (2022); see also id. at 680 (Kavanaugh, J., respecting denial of application for stay)

[snip]

Thus, even if any assertion of executive privilege by Plaintiff ultimately fails in this context, that possibility, even if likely, does not negate a former President’s ability to raise the privilege as an initial matter. Accordingly, because the Privilege Review Team did not screen for material potentially subject to executive privilege, further review is required for that additional purpose.

This is insane analysis. But the craziest part is that, with those words, “further review is required,” Aileen Cannon appoints herself President and overrides an Executive Privilege decision the actual President has already made.

Oh sure. She pretends the actual President hasn’t already weighed in.

Here’s how smothers Joe Biden — and the delegation he made to the Archives in May to make an Executive Privilege determination — with a pillow. On page 2, Cannon lays out the posture of this case this way.

On April 12, 2022, NARA notified Plaintiff that it intended to provide the Fifteen Boxes to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (“FBI”) the following week [ECF No. 48 p. 5]. Plaintiff then requested an extension on the contemplated delivery so that he could determine the existence of any privileged material [ECF No. 48-1 p. 7]. The White House Counsel’s Office granted the request [ECF No. 48-1 p. 7]. On May 10, 2022, NARA informed Plaintiff that it would proceed with “provid[ing] the FBI access to the records in question, as requested by the incumbent President, beginning as early as Thursday, May 12, 2022” [ECF No. 48-1 p. 9]. The Government’s filing states that the FBI did not obtain access to the Fifteen Boxes until approximately May 18, 2022 [ECF No. 48 p. 7].

She draws from page 5 of the government response and non-contiguous pages, page 7 and 9, from the letter Acting Archivist Debra Steidel Wall sent Evan Corcoran in May. She left out page 8 of the appendix, in which Steidel Wall said this:

[T]he Supreme Court’s decision in Nixon v. Administrator of General Services, 433 U.S. 425 (1977), strongly suggests that a former President may not successfully assert executive privilege “against the very Executive Branch in whose name the privilege is invoked.” Id. at 447-48. In Nixon v. GSA, the Court rejected former President Nixon’s argument that a statute requiring that Presidential records from his term in office be maintained in the custody of, and screened by, NARA’s predecessor agency-a “very limited intrusion by personnel in the Executive Branch sensitive to executive concerns”-would “impermissibly interfere with candid communication of views by Presidential advisers.” Id. at 451 ; see also id. at 455 (rejecting the claim). The Court specifically noted that an “incumbent President should not be dependent on happenstance or the whim of a prior President when he seeks access to records of past decisions that define or channel current governmental obligations.” Id. at 452; see also id. at 441-46 ( emphasizing, in the course of rejecting a separation-of-powers challenge to a provision of a federal statute governing the disposition of former President Nixon ‘s tape recordings, papers, and other historical materials “within the Executive Branch,” where the “employees of that branch [would] have access to the materials only ‘for lawful Government use,” ‘ that “[t]he Executive Branch remains in full control of the Presidential materials, and the Act facially is designed to ensure that the materials can be released only when release is not barred by some applicable privilege inherent in that branch”; and concluding that “nothing contained in the Act renders it unduly disruptive of the Executive Branch”).

It is not necessary that I decide whether there might be any circumstances in which a former President could successfully assert a claim of executive privilege to prevent an Executive Branch agency from having access to Presidential records for the performance of valid executive functions. The question in this case is not a close one. The Executive Branch here is seeking access to records belonging to, and in the custody of, the Federal Government itself, not only in order to investigate whether those records were handled in an unlawful manner but also, as the National Security Division explained, to “conduct an assessment of the potential damage resulting from the apparent manner in which these materials were stored and transported and take any necessary remedial steps.” These reviews will be conducted by current government personnel who, like the archival officials in Nixon v. GSA, are “sensitive to executive concerns.” Id. at 451. And on the other side of the balance, there is no reason to believe such reviews could “adversely affect the ability of future Presidents to obtain the candid advice necessary for effective decision-making.” Id. at 450. To the contrary: Ensuring that classified information is appropriately protected, and taking any necessary remedial action if it was not, are steps essential to preserving the ability of future Presidents to “receive the full and frank submissions of facts and opinions upon which effective discharge of [their] duties depends.” Id. at 449.

The bolded language, by the way, is a premise that Cannon adopts in letting the government continue its damage assessment. But she doesn’t cite it, probably because it would make clear not just how outlandish her argument is, but that this decision has already been made.

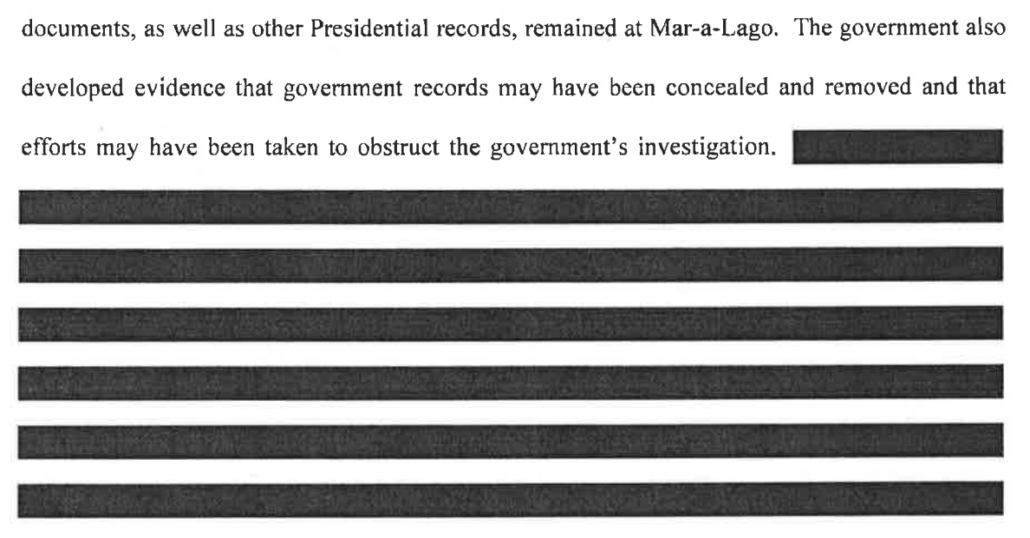

And Cannon cut out page 6 of the government response, which says this.

As the NARA Referral stated, the Fifteen Boxes contained “highly classified records.” Upon learning this, DOJ sought access to the Fifteen Boxes in part “so that the FBI and others in the Intelligence Community could examine them.” Wall Letter at 1. DOJ followed the steps outlined in the Presidential Records Act to obtain access to the Fifteen Boxes.

On April 12, 2022, NARA advised counsel for the former President that it intended to provide the FBI with the records the following week (i.e., the week of April 18). Id. at 2. That access was not provided then, however, because a representative of the former President requested an extension of the production date to April 29. See id. As the Acting Archivist recounted, on April 29, DOJ advised counsel for the former President as follows:

There are important national security interests in the FBI and others in the Intelligence Community getting access to these materials. According to NARA, among the materials in the boxes are over 100 documents with classification markings, comprising more than 700 pages. Some include the highest levels of classification, including Special Access Program (SAP) materials. Access to the materials is not only necessary for purposes of our ongoing criminal investigation, but the Executive Branch must also conduct an assessment of the potential damage resulting from the apparent manner in which these materials were stored and transported and take any necessary remedial steps. Accordingly, we are seeking immediate access to these materials so as to facilitate the necessary assessments that need to be conducted within the Executive Branch.

See id.

On the same date that DOJ sent this correspondence, counsel for the former President requested an additional extension before the materials were provided to the FBI and stated that in the event that another extension was not granted, the letter should be construed as “‘a protective assertion of executive privilege made by counsel for the former President.’” Id. In its May 10 response, NARA rejected both of counsel’s requests. First, NARA noted that significant time—four weeks—had elapsed since NARA first informed counsel of its intent to provide the documents to the FBI. Id. Second, NARA stated that the former President could not assert executive privilege to prevent others within the Executive Branch from reviewing the documents, calling that decision “not a close one.” Id. at 3. NARA rejected on the same basis counsel’s “‘protective assertion’” of privilege. Id. at 3-4. Accordingly, NARA informed counsel that it would provide the FBI access to the records beginning as early as Thursday, May 12, 2022. Id. at 4. Although the former President could have taken legal action prior to May 12 to attempt to block the FBI’s access to the documents in the Fifteen Boxes, he did not do so.

Again, Cannon simply ignores that these issues were resolved in May.

She also ignores something Julie Edelstein said in the hearing before her: that the government waited before accessing the 15 boxes turned over in January to give Trump a chance to claim Executive Privilege, which he never did.

Also notably, that letter was provided on May 10th. Purposefully, we waited a few days before beginning the FBI’s review of that material to give the Plaintiff the remedy he could have sought at that time, which was to bring a suit in the District of Colombia to assert executive privilege over those materials. He did not.

Aileen Cannon knows Joe Biden has already weighed in on the EP issue, but she pretends he hasn’t and decides that she, Aileen Cannon, must review hypothetical claims of EP raised against the Executive branch.

Stealing classified documents is not immediately incriminating

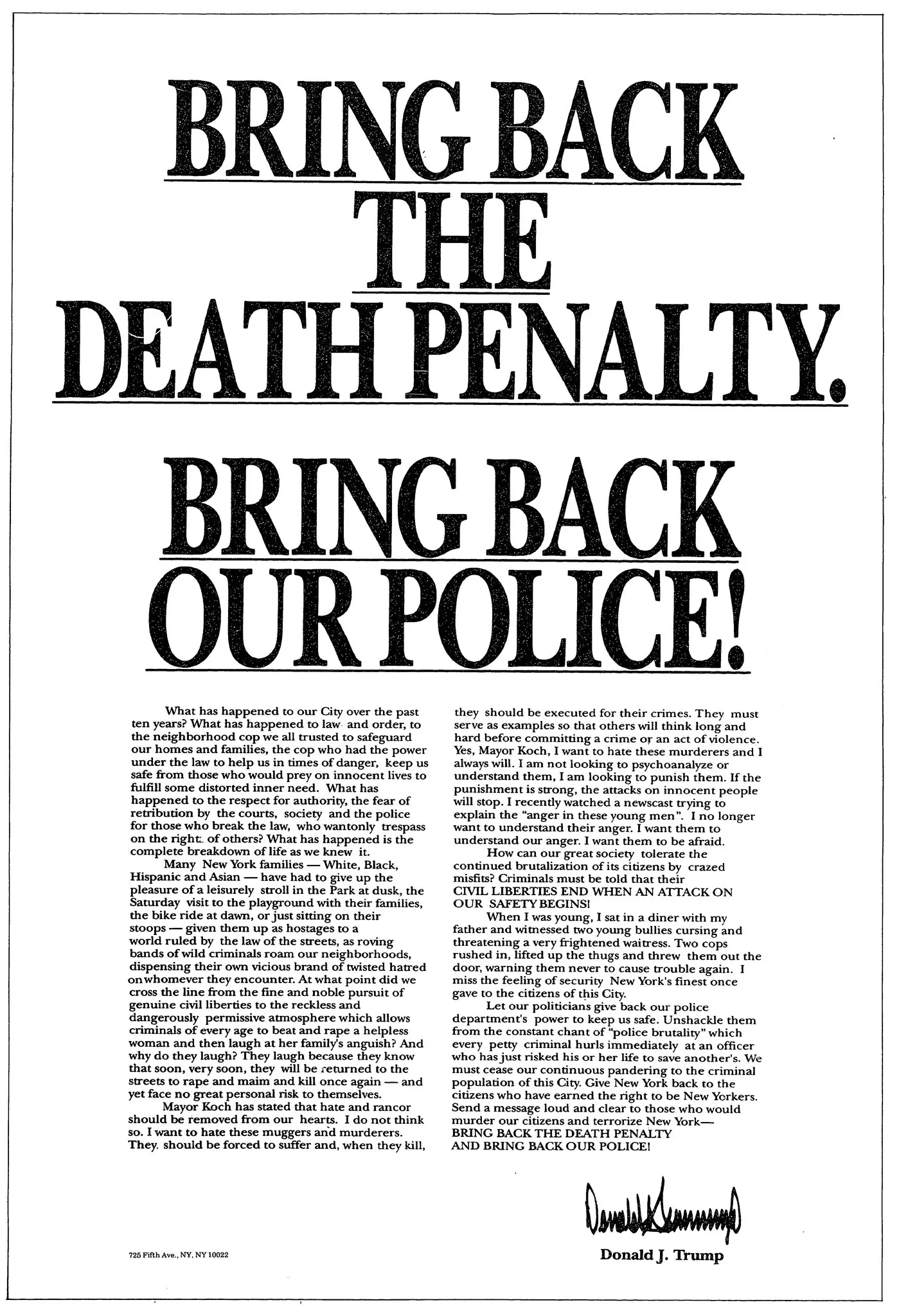

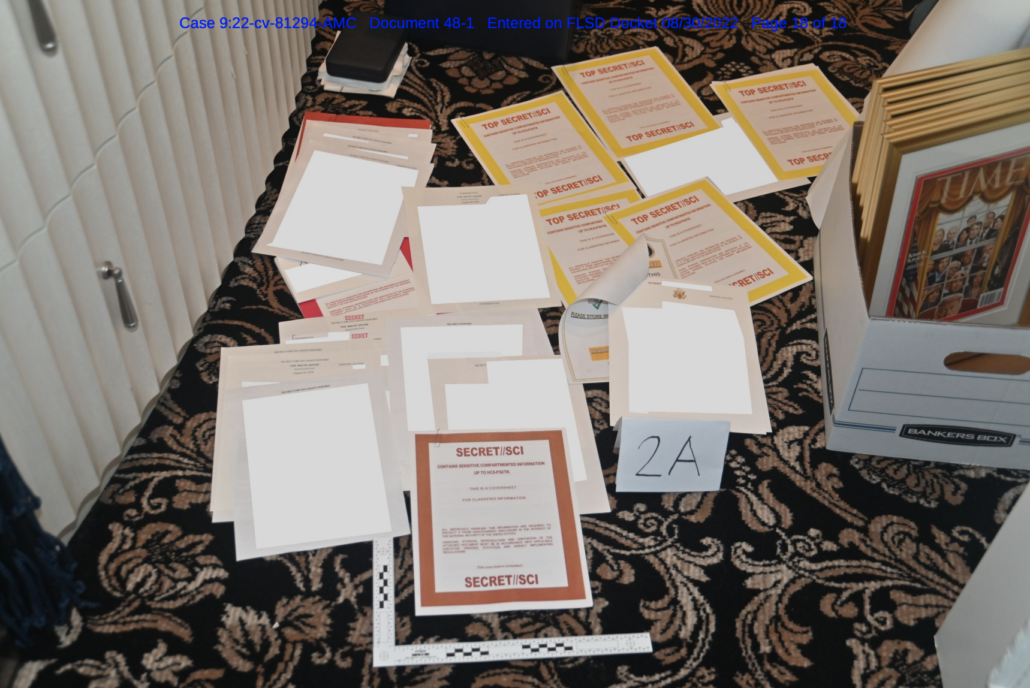

One of the funnier moves Cannon makes is in claiming that the seizure of these documents two months after Trump swore he had turned over all documents marked classified in his possession is not immediately incriminating.

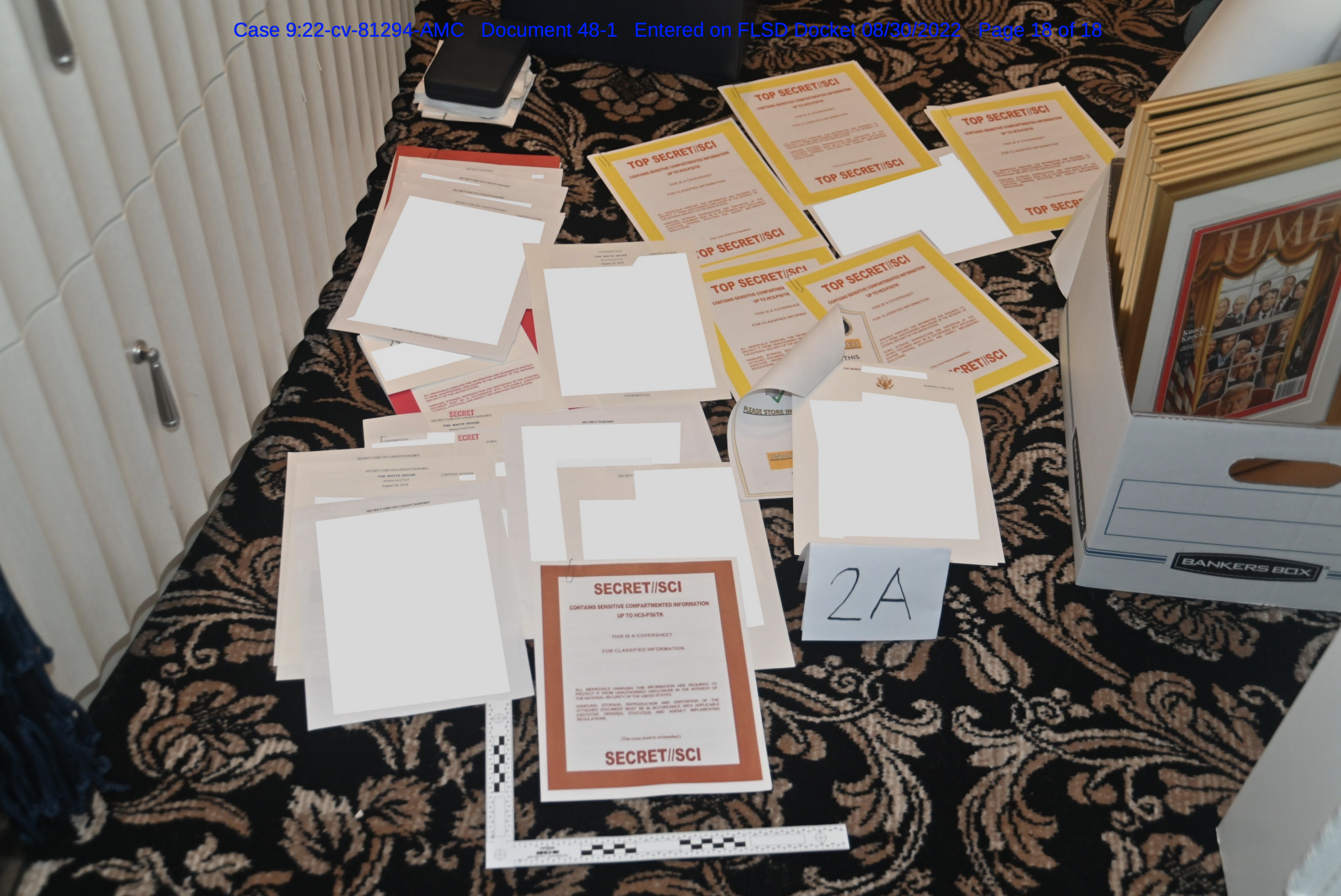

Importantly, after DOJ released this picture, Trump complained that FBI took a picture showing the documents in question in a condition other than he stored them in, a clear admission he had possessed them. Effectively, he has already confessed to the crime.

And it’s not just him either. In the hearing, Jim Trusty scoffed that showing smoking gun proof that DOJ caught Trump with documents that his Custodian of Records swore he did not have would be relevant to the question of a Special Master.

You even have what happened two days ago, the insertion in a motion about the special master of a perfectly staged photograph of classified covers on documents. I mean, how that was supposed to help the Court decide the issue of special master is beyond me.

Trump and his lawyers have admitted that these documents were seized at Mar-a-Lago.

That’s relevant to an invocation of an 11th Circuit precedent ruling that Jay Bratt made in the hearing. someone does not have standing to make a Rule 41(g) motion over material he obtained via crime.

The sort of standing or jurisdiction that you have to have right now pre-indictment as set forth in Rule 41(g), as set forth in the Howell case, and as I’m about to talk with respect to the equity jurisdiction Bennett case that Judge Rosenbaum decided when she was a judge here, that is very limited. And whether you call it “standing” or “jurisdiction,” they do not have it here. And in order to get the jurisdiction or standing under Rule 41(g), that is a key requirement. In fact, it is the key requirement, that you have a possessory interest in a property. If, at a later point, the Fourth Amendment — potential Fourth Amendment violations need to be vindicated, that is done through a motion on suppression. It is not done through a Rule 41(g) motion pre-indictment.

[snip]

There are also, you know, three I think very important, overarching factors that the courts emphasize when a judge in your position is being asked to exercise equity jurisdiction for return of property. One is that the exercise of that jurisdiction must be with caution and restraint, and it must be exercised only to prevent a manifest injustice; and the third, any time a party comes to equity, the party must have clean hands. And here, the former President being in unlawful possession of classified and other Presidential records, that is a text book example of unclean hands.

Cannon argues that because Howell pertained to someone who had already pled guilty, it is inapt here. Note that she relies, again, on the personal documents she herself refused to let DOJ share with Trump’s lawyers.

At the hearing, the Government argued that the equitable concept of “unclean hands” bars Plaintiff from moving under Rule 41(g), citing United States v. Howell, 425 F.3d 971, 974 (11th Cir. 2005) (“[I]n order for a district court to grant a Rule 41(g) motion, the owner of the property must have clean hands.”). Howell involved a defendant who pled guilty to conspiring to distribute cocaine and then sought the return of $140,000 in government-issued funds that were seized from him following a drug sale to a confidential source. Id. at 972–73. That case is not factually analogous to the circumstances presented and does not provide a basis to decline to exercise equitable jurisdiction here. Plaintiff has not pled guilty to any crimes; the Government has not clearly explained how Plaintiff’s hands are unclean with respect to the personal materials seized; and in any event, this is not a situation in which there is no room to doubt the immediately apparent incriminating nature of the seized material, as in the case of the sale of cocaine.

Cannon is all worked up over whether Trump is guilty, and not that under Howell, Trump has an affirmative requirement to prove he owns the stuff seized before she can grant him relief.

In order for an owner of property to invoke Rule 41(g), he must show that he had a possessory interest in the property seized by the government.

But even the unclean hands language requires analysis, first, of whether Trump legally possessed the items at issue.

Furthermore, in order for a district court to grant a Rule 41(g) motion, the owner of the property must have clean hands. See Gaudiosi v. Mellon, 269 F.2d 873, 881-82 (3d Cir.1959)(stating, no principle is better settled than the maxim that he who comes into equity must come with “clean hands” and keep them clean throughout the course of the litigation, and that if he violates this rule, he must be denied all relief whatever may have been the merits of his claim.)

The doctrine of “unclean hands” is an equitable test that is used by courts in deciding equitable fate.

As Cannon has already conceded, that question can only be determined in the DC District, not by a Special Master in SDFL.

Remember: Trump might not even own the things (identified in the privilege report and so unavailable to Bratt to address) on which Cannon has rested all her analysis. It could well be White House Counsel materials about the Mazars case or White House Physician materials about his near-death from COVID. Trump hasn’t made the argument they are his either (he instead relied on the passports that she ignored).

But based on first, her refusal to let DOJ share that material with Trump, and then her declaration that he does own it, Cannon has overturned the property structure before her, the 11,000 stolen government documents and the Executive Privilege that Biden has already, by delegation, asserted. Rather than forcing Trump to prove he owns this property, she’s just giving him default ownership of it.

In her desperation to shut down a criminal investigation into the theft of government documents, including highly classified ones, Aileen Cannon engages in large-scale appropriation of taxpayer owned property.

Update: Thanks for the corrections that Cannon was born in Colombia, not Cuba.