Carter Page Believed James Wolfe Was Ellen Nakashima’s Source Disclosing His FISA Application Less than a Month After the Story

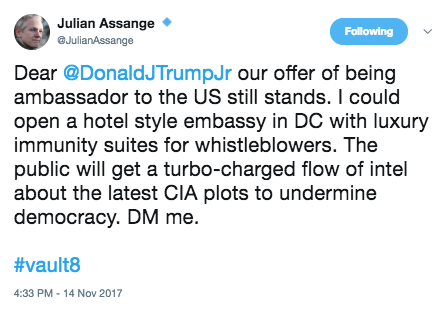

According to the Statement of Offense to which James Wolfe — the former Senate Intelligence Committee security official convicted of lying about his contacts with journalists — allocuted, Carter Page suspected Wolfe was the source for Ellen Nakashima’s story revealing Page had been targeted with a FISA order. When the former Trump campaign staffer wrote Nakashima to complain about the story less than four weeks after Washington Post published it, Page BCCed Wolfe. [Nakashima is Reporter #1 and Ali Watkins is Reporter #2.]

On May 8, 2017, MALE-1 emailed REPORTER #1 complaining about REPORTER #1’s reporting of him (MALE-1). According to the metadata recovered during the search of Wolfe’s email, Wolfe was blind-copied on that email by MALE-1.

That unexplained detail is important — albeit mystifying — background to two recent stories on leak investigations.

First, as reported last month, Nakashima was one of three journalists whose call records DOJ obtained last year.

The Trump Justice Department secretly obtained Washington Post journalists’ phone records and tried to obtain their email records over reporting they did in the early months of the Trump administration on Russia’s role in the 2016 election, according to government letters and officials.

In three separate letters dated May 3 and addressed to Post reporters Ellen Nakashima and Greg Miller, and former Post reporter Adam Entous, the Justice Department wrote they were “hereby notified that pursuant to legal process the United States Department of Justice received toll records associated with the following telephone numbers for the period from April 15, 2017 to July 31, 2017.” The letters listed work, home or cellphone numbers covering that three-and-a-half-month period.

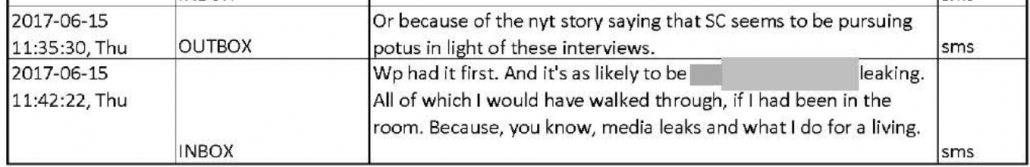

The scope of the records obtained on the WaPo journalists last year started four days after the Page story, so while some May 11, 2017 emails between Nakashima and Wolfe would have been included in what got seized last year, any contacts prior to the FISA story would not have. And the public details on the prosecution of Wolfe show no sign that Nakashima’s records were obtained in that investigation (those of Ali Watkins, whom Wolfe was in a relationship, however, were). Indeed, the sentencing memo went out of its way to note that DOJ had not obtained deleted Signal texts from any journalists. “The government did not recover or otherwise obtain from any reporters’ communications devices or related records the content of any of these communications.”

That said, Nakashima’s reporting was targeted in two different leak investigations, covering sequential periods, three years apart.

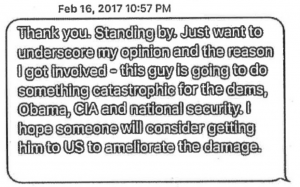

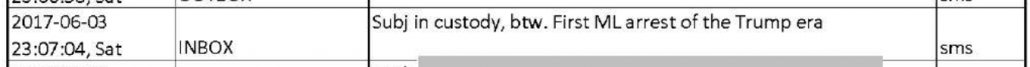

It’s not clear how quickly the Page investigation focused on Wolfe. But it may have outside help. A CBP Agent unconnected to the FBI investigation grilled Watkins on her ties with Wolfe in June 2017.

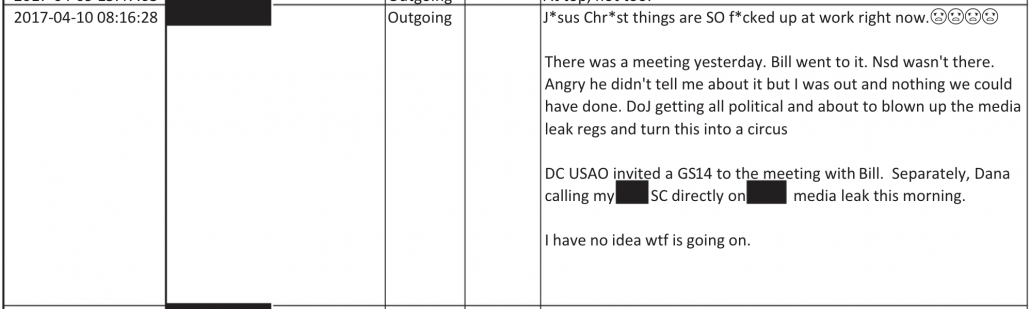

The Sentencing Memorandum on Wolfe suggests the FBI came to focus on him — and excused their focus — after having learned of his affair with Watkins. They informed Richard Burr and Mark Warner, and obtained the first of several warrants to access his phone.

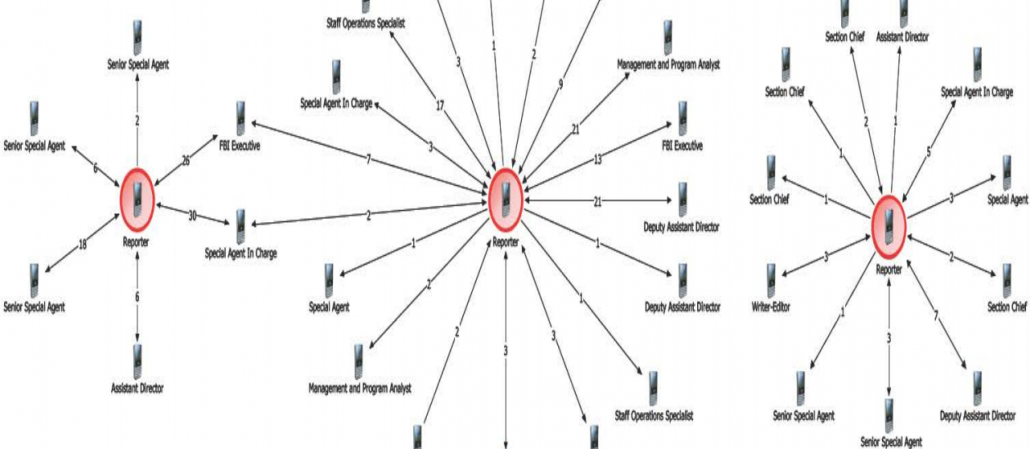

At the time the classified national security information about the FISA surveillance was published in the national media, defendant James A. Wolfe was the Director of Security for the SSCI. He was charged with safeguarding information furnished to the SSCI from throughout the United States Intelligence Community (“USIC”) to facilitate the SSCI’s critical oversight function. During the course of the investigation, the FBI learned that Wolfe had been involved in the logistical process for transporting the FISA materials from the Department of Justice for review at the SSCI. The FBI also discovered that Wolfe had been involved in a relationship with a reporter (referred to as REPORTER #2 in the Indictment and herein) that began as early as 2013, when REPORTER #2, then a college intern, published a series of articles containing highly sensitive U.S. government information. Between 2014 and 2017, Wolfe and REPORTER #2 exchanged tens of thousands of telephone calls and electronic messages. Also during this period, REPORTER #2 published dozens of news articles on national security matters that contained sensitive information related to the SSCI.

Upon realizing that Wolfe was engaged in conduct that appeared to the FBI to compromise his ability to fulfill his duties with respect to the handling of Executive Branch classified national security information as SSCI’s Director of Security, the FBI faced a dilemma. The FBI needed to conduct further investigation to determine whether Wolfe had disseminated classified information that had been entrusted to him over the past three decades in his role as SSCI Director of Security. To do that, the FBI would need more time to continue their investigation covertly. Typically, upon learning that an Executive Branch employee and Top Secret clearance holder had potentially been compromised in place – such as by engaging in a clandestine affair with a national security reporter – the FBI would routinely provide a “duty-to-warn” notification to the relevant USIC equity holder in order to allow the intelligence agencies to take mitigation measures to protect their national security equities. Here, given the sensitive separation of powers issue and the fact that the FISA was an FBI classified equity, the FBI determined that it would first conduct substantial additional investigation and monitoring of Wolfe’s activities. The FBI’s executive leadership also took the extraordinary mitigating step of limiting its initial notification of investigative findings to the ranking U.S. Senators who occupy the Chair and Vice Chair of the SSCI.2

The FBI obtained court authority to conduct a delayed-notice search warrant pursuant to 18 U.S.C. § 3103a(b), which allowed the FBI to image Wolfe’s smartphone in October 2017. This was conducted while Wolfe was in a meeting with the FBI in his role as SSCI Director of Security, ostensibly to discuss the FBI’s leak investigation of the classified FISA material that had been shared with the SSCI. That search uncovered additional evidence of Wolfe’s communications with REPORTER #2, but it did not yet reveal his encrypted communications with other reporters.

This process — as described by Jocelyn Ballantine and Tejpal Chawla, prosecutors involved in some of the other controversial subpoenas disclosed in the last month — is a useful lesson of how the government proceeded in a case that likely overlapped with the investigation into HPSCI that ended up seizing Swalwell and Schiff’s records. Given that Swalwell was targeted by a Chinese spy, it also suggests one excuse they may have used to obtain the records: by claiming it was a potential compromise.

Still, by the time FBI first informed Wolfe of the investigation, in October 2017, they had obtained his cell phone content showing that he was chatting up other journalists, in addition to Watkins — and indeed, he continued to share information on Page. By the time the FBI got Wolfe to perjure himself on a questionnaire about contacts with journalists in December 2017, they had presumably already searched Watkins’ emails going back years. Wolfe was removed from his position and stripped of clearance, making his indictment six months later only a matter of time.

All that said, the government never proved that Wolfe was the source for Nakashima. And Ballantine’s subpoena for HPSCI contacts, weeks later after FBI searched Wolfe’s phone, may have reflected a renewed attempt to pin the leak on someone, anyone (though it’s not clear whether investigators looked further than Congress, or even to Paul Ryan, who has been suspected of tipping Page off.

If the James Wolfe investigation reflects how they might have approached the HPSCI side, there’s one other alarming detail of this: The FBI alerted someone in Congress of the search, the Chair and Ranking Member of the Committee. But in HPSCI’s case, Schiff was the Ranking Member. Meaning it’s possible that, by targeting on Schiff, FBI gave itself a way to consult only with the Republican Chair of the Committee.

James Wolfe (and the investigation of Natalie Sours Edwards, who was sentenced to six months in prison last week) are an important lesson in leak investigations that serves as important background for Joe Biden’s promise that reporters won’t be targeted anymore. The way you conduct a leak investigation in this day and age is to seize the source’s phone, in part because that’s the only way to obtain Signal texts.

Timeline

March 2017: Exec Branch provides SSCI “the Classified Document,” which includes both Secret and Top Secret information, with details pertaining to Page classified as Secret.

March 2, 2017: James Comey briefs HPSCI on counterintelligence investigations, with a briefing to SSCI at almost the same time.

March 17, 2017: 82 text messages between Wolfe and Watkins.

April 3, 2017: Watkins confirms that Carter Page is Male-1.

April 11, 2017: WaPo reports FBI obtained FISA order on Carter Page.

June 2017: End date of five communications with Reporter #1 via Wolfe’s SSCI email.

June 2017: Using pretext of serving as a source, CBP agent Jeffrey Rambo grills Watkins about her travel with Wolfe.

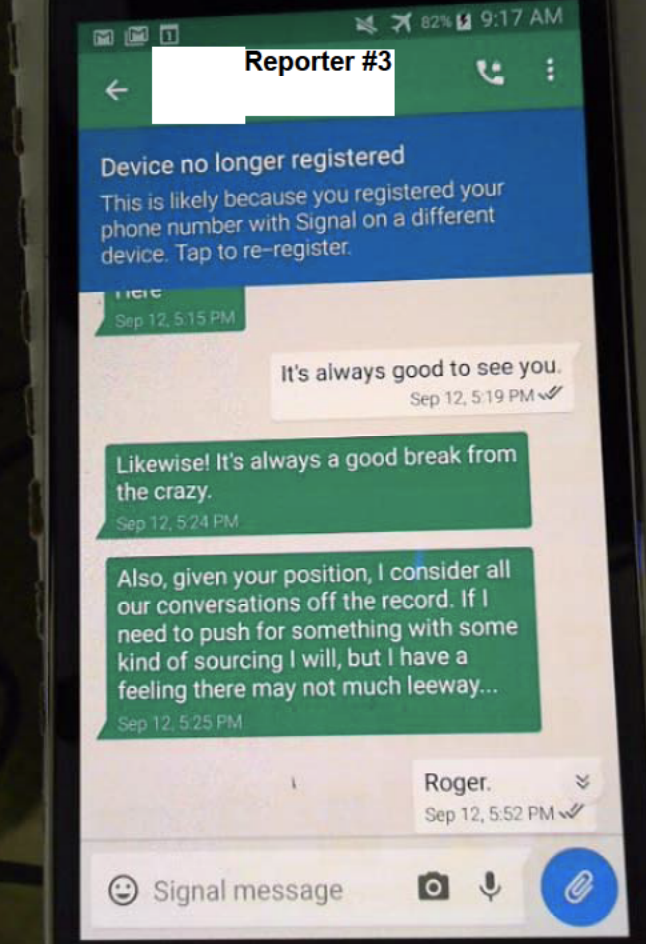

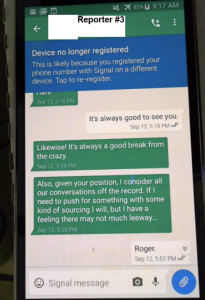

October 2017: Wolfe offers up to be anonymous source for Reporter #4 on Signal.

October 16, 2017: Wolfe Signals Reporter #3 about Page’s subpoena.

October 17, 2017: NBC reports Carter Page subpoena.

October 24, 2017: Wolfe informs Reporter #3 of timing of Page’s testimony.

October 30, 2017: FBI informs James Wolfe of investigation.

November 15, 2017: 90 days before DOJ informs Ali Watkins they’ve seized her call records.

December 14, 2017: FBI approaches Watkins about Wolfe.

Prior to December 15, 2017 interview: Wolfe writes text message to Watkins about his support for her career.

December 15, 2017: FBI interviews Wolfe.

January 11, 2018: Second interview with Wolfe, after which FBI executes a Rule 41 warrant on his phone, discovering deleted Signal texts with other journalists.

February 6, 2018: Subpoena targeting Adam Schiff and others.

February 13, 2018: DOJ informs Watkins they’ve seized her call records.

June 6, 2018: Senate votes to make official records available to DOJ.

That the Chairman and Vice Chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, acting jointly, are authorized to provide to the United States Department of Justice copies of Committee records sought in connection with a pending investigation arising out of allegations of the unauthorized disclosure of information, except concerning matters for which a privilege should be asserted.

June 7, 2018: Grand jury indicts Wolfe.

June 7, 2018: Richard Burr and Mark Warner release a statement:

We are troubled to hear of the charges filed against a former member of the Committee staff. While the charges do not appear to include anything related to the mishandling of classified information, the Committee takes this matter extremely seriously. We were made aware of the investigation late last year, and have fully cooperated with the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Department of Justice since then. Working through Senate Legal Counsel, and as noted in a Senate Resolution, the Committee has made certain official records available to the Justice Department.

June 13, 2018: Wolfe arraigned in DC. His lawyers move to prohibit claims he leaked classified information.