Update: Jennifer Granick (who unlike me, is a lawyer) says telecoms will be subject to suit if they continue to comply with dragnet orders.

Any company that breaches confidentiality except as required by law is liable for damages and attorneys’ fees under 47 U.S.C. 206. And there is a private right of action under 47 U.S.C. 207.

Note that there’s no good faith exception in the statute, no immunity for acting pursuant to court order. Rather, the company is liable unless it was required by law to disclose. So Verizon could face a FISC 215 dragnet order on one side and an order from the Southern District of New York enjoining the dragnet on the other. Is Verizon required by law to disclose in those circumstances? If not, the company could be liable. And did I mention the statute provides for attorneys’ fees?

Everything is different now than it was last week. Reauthorization won’t protect the telecoms from civil liability. It won’t enable the dragnet. As of last Thursday, the dragnet is dead, unless a phone company decides to put its shareholders’ money on the line to maintain its relationships with the intelligence community.

Last night, Mitch McConnell introduced a bill for a 2-month straight reauthorization of the expiring PATRIOT provisions as well as USA F-ReDux under a rule that bypasses Committee structure, meaning he will be able to bring that long-term straight reauthorization, that short term one, or USA F-ReDux to the floor next week.

Given that a short term reauthorization would present a scenario not envisioned in Gerard Lynch’s opinion ruling the Section 215 dragnet unlawful, it has elicited a lot of discussion about how the Second Circuit, FISC, and the telecoms might respond in case of a short term reauthorization. But these discussions are almost entirely divorced from some evidence at hand. So I’m going to lay out what we know about both past telecom and FISA Court behavior.

Because of the details I lay out below, I predict that so long as Congress looks like it is moving towards an alternative, both the telecoms and the FISC will continue the phone dragnet in the short term, and the Second Circuit won’t weigh in either.

The phone dragnet will continue for another six months even under USA F-ReDux

As I pointed out here, even if USA F-ReDux passed tomorrow, the phone dragnet would continue for another 6 months. That’s because the bill gives the government 180 days — two dragnet periods — to set up the new system.

(a) IN GENERAL.—The amendments made by sections 101 through 103 shall take effect on the date that is 180 days after the date of the enactment of this Act.

(b) RULE OF CONSTRUCTION.—Nothing in this Act shall be construed to alter or eliminate the authority of the Government to obtain an order under title V of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (50 U.S.C. 24 1861 et seq.) as in effect prior to the effective date described in subsection (a) during the period ending on such effective date.

The Second Circuit took note of USA F-ReDux specifically in its order, so it would be hard to argue that it doesn’t agree Congress has the authority to provide time to put an alternative in place. Which probably means (even though I oppose Mitch’s short-term reauth in most scenarios) that the Second Circuit isn’t going to balk — short of the ACLU making a big stink — at a short term reauth for the purported purpose of better crafting a bill that reflects the intent of Congress. (Though the Second Circuit likely won’t look all that kindly on Mitch’s secret hearing the other day, which violates the standards of debate the Second Circuit laid out.)

Heck, the Second Circuit waited 8 months — and one failed reform effort — to lay out its concerns about the phone dragnet’s legality that were, in large part, fully formed opinions at least September’s hearing. The Second Circuit wants Congress to deal with this and they’re probably okay with Congress taking a few more months to do so.

FISC has already asked for briefing on any reauthorization

A number of commentators have also suggested that the Administration could just use the grandfather clause in the existing sunset to continue collection or might blow off the Appeals Court decision entirely.

But the FISC is not sitting dumbly by, oblivious to the debate before Congress and the Courts. As I laid out here, in his February dragnet order, James Boasberg required timely briefing from the government in each of 3 scenarios:

- A ruling from an Appellate Court

- Passage of USA F-ReDux introduces new issues of law that must be considered

- A plan to continue production under the grandfather clause

And to be clear, the FISC has not issued such an order in any of the publicly released dragnet orders leading up to past reauthorizations, not even in advance of the 2009-2010 reauthorizations, which happened at a much more fraught time from the FISC’s perspective (because FISC had had to closely monitor the phone dragnet production for 6 months and actually shut down the Internet dragnet in fall 2009). The FISC clearly regards this PATRIOT sunset different than past ones and plans to at least make a show of considering the legal implications of it deliberately.

FISC does take notice of other courts

Of course, all that raises questions about whether FISC feels bound by the Second Circuit decision — because, of course, it has its very own appellate court (FISCR) which would be where any binding precedent would come from.

There was an interesting conversation on that topic last week between (in part) Office of Director of National Intelligence General Counsel Bob Litt and ACLU’s Patrick Toomey (who was part of the team that won the Second Circuit decision). That conversation largely concluded that FISC would probably not be bound by the Second Circuit, but Litt’s boss, James Clapper (one of the defendants in the suit) would be if the Second Circuit ever issued an injunction.

Sunlight Foundation’s Sean Vitka: Bob, I have like a jurisdictional question that I honestly don’t know the answer to. The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. They say that this is unlawful. Obviously there’s the opportunity to appeal to the Supreme Court. But, the FISA Court of Review is also an Appeals Court. Does the FISC have to listen to that opinion if it stands?

Bob Litt: Um, I’m probably not the right person to ask that. I think the answer is no. I don’t think the Second Circuit Court of Appeals has direct authority over the FISA Court. I don’t think it’s any different than a District Court in Idaho wouldn’t have to listen to the Second Circuit’s opinion. It would be something they would take into account. But I don’t think it’s binding upon them.

Vitka: Is there — Does that change at all given that the harms that the Second Circuit acknowledged are felt in that jurisdiction?

Litt: Again, I’m not an expert in appellate jurisdiction. I don’t think that’s relevant to the question of whether the Second Circuit has binding authority over a court that is not within the Second Circuit. I don’t know Patrick if you have a different view on that?

Third Way’s Mieke Eoyang: But the injunction would be, right? If they got to a point where they issued an injunction that would be binding…

Litt: It wouldn’t be binding on the FISA Court. It would be binding on the persons who received the —

Eoyong: On the program itself.

Patrick Toomey: The defendants in the case are the agency officials. And so an injunction issued by the Second Circuit would be directed at those officials.

But there is reason to believe — even beyond FISC’s request for briefing on this topic — that FISC will take notice of the Second Circuit’s decision, if not abide by any injunction it eventually issues.

That’s because, twice before, it has even taken notice of magistrate judge decisions.

The first known example came in the weeks before the March 2006 reauthorization of the PATRIOT Act would go into effect. During 2005, several magistrate judges had ruled that the government could not add a 2703(d) order to a pen register to obtain prospective cell site data along with other phone data. By all appearances, the government was doing the same with the equivalent FISA orders (this application of a “combined” Business Record and Pen Register order is redacted in the 2008 DOJ IG Report on Section 215, but contextually it’s fairly clear this is close to what happened). Those magistrate decisions became a problem when, in 2005, Congress limited Section 215 order production to that which could be obtained with a grand jury subpoena. Effectively, the magistrates had said you couldn’t get prospective cell site location with just a subpoena, which therefore would limit whether FBI could get cell site location with a Section 215 order.

While it is clear that FISC required briefing on this point, it’s not entirely clear what FISC’s response was. For a variety of reasons, it appears FISC stopped these combined application sometime in 2006 — the reauthorization went into effect in March 2006 — though not immediately (which suggests, in the interim, DOJ just found a new shell to put its location data collection under).

The other time FISC took notice of magistrate opinions pertained to Post Cut Through Dialed Digits (those are the things like pin and extension numbers you dial after your call or Internet connection has been established). From 2006 through 2009, some of the same magistrates ruled the government must set its pen register collection to avoid collecting PCTDD. By that point, FISC appears to have already ruled the government could collect that data, but would have to deal with it through minimization. But the FISC appears to have twice required the government to explain whether and how its minimization of PCTDD did not constitute the collection of content, though it appears that in each case, FISC permitted the government to go on collecting PCTDD under FISA pen registers. (Note, this is another ruling that may be affected by the Second Circuit’s focus on the seizure, not access, of data.)

In other words, even on issues not treating FISC decisions specifically, the FISC has historically taken notice of decisions made in courts that have no jurisdiction over its decisions (and in one case, FISC appears to have limited government production as a result). So it would be a pretty remarkable deviation from that past practice for FISC to completely blow off the Second Circuit decision, even if it may not feel bound by it.

Verizon responds to court orders, but in half-assed fashion

Finally, there’s the question of how the telecoms will react to the Second Circuit decision. And even there, we have some basis for prediction.

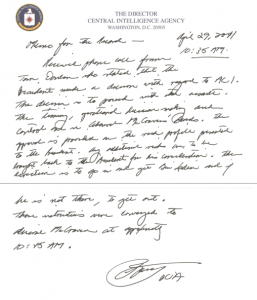

In January 2014, after receiving the Secondary Order issued in the wake of Judge Richard Leon’s decision in Klayman v. Obama that the dragnet was unconstitutional, Verizon made a somewhat half-assed challenge to the order.

Leon issued his decision December 16. Verizon did not ask the FISC for guidance (which makes sense because they are only permitted to challenge orders).

Verizon got a new Secondary Order after the January 3 reauthorization. It did not immediately challenge the order.

It only got around to doing so on January 22 (interestingly, a few days after ODNI exposed Verizon’s role in the phone dragnet a second time), and didn’t do several things — like asking for a hearing or challenging the legality of the dragnet under 50 USC 1861 as applied — that might reflect real concern about anything but the public appearance of legality. (Note, that timing is of particular interest, given that the very next day, on January 23, PCLOB would issue its report finding the dragnet did not adhere to Section 215 generally.)

Indeed, this challenge might not have generated a separate opinion if the government weren’t so boneheaded about secrecy.

Verizon’s petition is less a challenge of the program than an inquiry whether the FISC has considered Leon’s opinion.

It may well be the case that this Court, in issuing the January 3,2014 production order, has already considered and rejected the analysis contained in the Memorandum Order. [redacted] has not been provided with the Court’s underlying legal analysis, however, nor [redacted] been allowed access to such analysis previously, and the order [redacted] does not refer to any consideration given to Judge Leon’s Memorandum Opinion. In light of Judge Leon’s Opinion, it is appropriate [redacted] inquire directly of the Court into the legal basis for the January 3, 2014 production order,

As it turns out, Judge Thomas Hogan (who will take over the thankless presiding judge position from Reggie Walton next month) did consider Leon’s opinion in his January 3 order, as he noted in a footnote.

And that’s about all the government said in its response to the petition (see paragraph 3): that Hogan considered it so the FISC should just affirm it.

Verizon didn’t know that Hogan had considered the opinion, of course, because it never gets Primary Orders (as it makes clear in its petition) and so is not permitted to know the legal logic behind the dragnet unless it asks nicely, which is all this amounted to at first.

Ultimately, Verizon asked to see proof that FISC had considered Leon’s decision. But it did not do any of the things people think might happen here — it did not immediately cease production, it did not itself challenge the legality of the dragnet, and it did not even ask for a hearing.

Verizon just wanted to make sure it was covered; it did not, apparently, show much concern about continued participation in it.

And this is somewhat consistent with the request for more information Sprint made in 2009.

So that’s what Verizon would do if it received another Secondary Order in the next few weeks. Until such time as the Second Circuit issues an injunction, I suspect Verizon would likely continue producing records, even though it might ask to see evidence that FISC had considered the Second Circuit ruling before issuing any new orders.