Update: 8/28/19: I just re-read this amid discussion that Andrew McCabe may be fired. Much of this I stand by. I was right about the import of Mike Flynn already pleading guilty, I stand by my comments about Michael Horowitz and think the IG Report is damning, though in his lawsuit, McCabe credibly argues it was no developed in the normal fashion. I was right that McCabe would not be a big witness in any obstruction investigation; I was wrong that Comey wouldn’t be. But I want to admit that obstruction did end up being what Mueller effectively issued an impeachment referral for. That said, there was obstruction in both the Stone and Manafort threads of any interactions with Russia.

I’m going to refrain from making any conclusions about Andy McCabe’s firing until we have the Inspector General Report that underlies it. For now (update: I’ve now cleaned this up post-Yoga class), keep the following details in mind:

Michael Horowitz is a very good Inspector General

The allegations that McCabe lacked candor in discussions about his communications with Devlin Barrett all arise out of an investigation Democrats demanded in response to FBI’s treatment of the investigation into Hillary Clinton. It is being led by DOJ’s Inspector General, Michael Horowitz. Horowitz was nominated by Barack Obama and confirmed while Democrats still had the majority, in 2012.

I’ve never seen anything in Horowitz’ work that suggests he is influenced by politics, though he has shown an ability to protect his own department’s authority, in part by cultivating Congress. Of significant note, he fought with FBI to get the information his investigators needed to do the job, but was thwarted, extending into Jim Comey’s tenure (as I laid out in a fucking prescient post written on November 3, 2016).

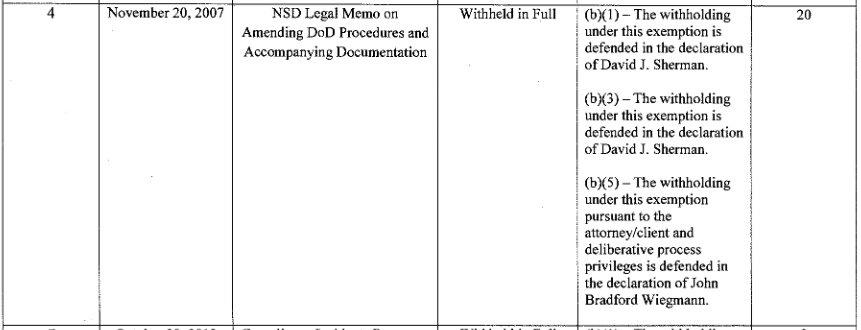

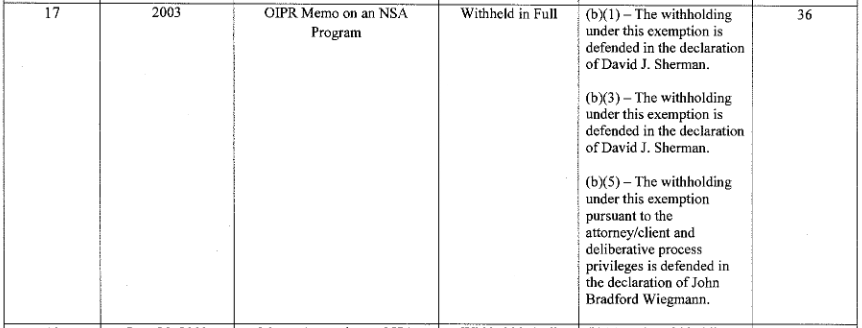

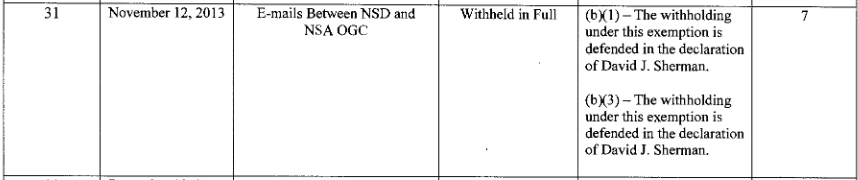

As I’ve long covered, in 2010, the FBI started balking at the Inspector General’s proper investigative demands. Among other things, the FBI refused to provide information on grand jury investigations unless some top official in FBI said that it would help the FBI if the IG obtained it. In addition, the FBI (and DEA) have responded to requests very selectively, pulling investigations they don’t want to be reviewed. In 2014, the IG asked OLC for a memo on whether it should be able to get the information it needs to do its job. Last year, OLC basically responded, Nope, can’t have the stuff you need to exercise proper oversight of the FBI.

DOJ’s Inspector General, Michael Horowitz, has been trying for some time to get Congress to affirmatively authorize his office (and IGs generally, because the problem exists at other agencies) to receive the information he needs to do his job. But thus far — probably because Jim Comey used to be known as the world’s biggest Boy Scout — Congress has failed to do so.

I care about how FBI’s misconduct affects the election (thus far, polling suggests it hasn’t done so, though polls are getting closer as Republican Gary Johnson supporters move back to supporting the GOP nominee, as almost always happens with third party candidates). But I care even more about how fucked up the FBI is. Even if Comey is ousted, I can’t think of a likely candidate that could actually fix the problems at FBI. One of the few entities that I think might be able to do something about the stench at FBI is the IG.

Except the FBI has spent 6 years making sure the IG can’t fully review its conduct.

So while I don’t think he’d be motivated by politics, he has had a running fight with top FBI officials about their willingness to subject FBI to scrutiny for the entirety of the Comey tenure.

McCabe has suggested that the investigation into him was “accelerated” only after he testified to the House Intelligence Committee that he would corroborate Jim Comey’s version of his firing.

I am being singled out and treated this way because of the role I played, the actions I took, and the events I witnessed in the aftermath of the firing of James Comey. The release of this report was accelerated only after my testimony to the House Intelligence Committee revealed that I would corroborate former Director Comey’s accounts of his discussions with the President. The OIG’s focus on me and this report became a part of an unprecedented effort by the Administration, driven by the President himself, to remove me from my position, destroy my reputation, and possibly strip me of a pension that I worked 21 years to earn. The accelerated release of the report, and the punitive actions taken in response, make sense only when viewed through this lens.

I’m not sure this timeline bears out (the investigation was supposed to be done last year, but actually got extended into this year). The statement stops short of saying that he was targeted because his testimony — presumably already delivered to Robert Mueller by the time of his HPSCI testimony — corroborated Comey’s.

What we’ve seen of the other personnel moves as a result of this investigation — the reassignment of Peter Strzok and Lisa Page for texts that really did raise conflict issues (to say nothing of operational security problems), and the reassignment of James Baker — seem reasonable. McCabe’s firing was reviewed by a whole bunch of people who have been around DOJ a long time.

So it’s possible the underlying claim has merit. It’s also possible that McCabe is getting the same punishment that a line agent would get if he did not answer the IG honestly.

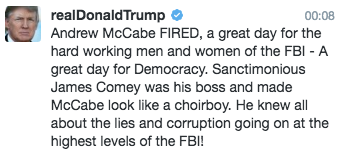

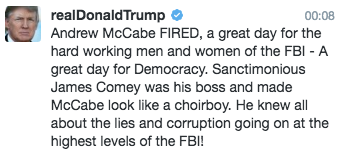

Trump’s comments matter

Obviously, all that cannot be taken out of context of Trump’s own statements and Jeff Sessions’ efforts to keep his job.

We will get these details in upcoming days, and almost all the details will come from people who’ve got a big stake in the process.

Michael Bromwich — McCabe’s lawyer — says they didn’t get a review of the allegations against McCabe until very recently, and were still trying to contest the firing two days ago (as was publicly reported). I find his claim that this was “cleaved off” from the larger investigation unconvincing: so were Strzok and Page, but that was done to preserve the integrity of the Mueller investigation, and Chris Wray had said publicly that he wanted to act on problems as they found them. Bromwich curiously is not saying that McCabe’s firing violates any agreement McCabe made when he took leave to await retirement.

Undoubtedly, Jeff Sessions did this in the most cowardly way possible. While I think it’s likely, I’m not 100% convinced that the timing was anything other than trying to make a real decision rather than let the retirement make it.

There’s no evidence, yet, that McCabe will lose all his pension

It has been said for over a month that McCabe was just waiting out his birthday so he could “get” his pension. That was so he could start drawing on it immediately. Josh Gerstein laid out the best thing I’ve seen on the implications (as well as what limited legal recourse McCabe has).

The financial stakes for McCabe could be significant. If he had made it to his 50th birthday on Sunday while still in federal service, he would have been eligible to begin drawing a full pension immediately under provisions that apply to federal law enforcement officers, said Kimberly Berry, a lawyer in Arlington, Virginia, who specializes in federal retirement issues.

Berry disputed reports, however, that McCabe would lose his pension altogether.

“He doesn’t lose his retirement,” she said. “It’s not all thrown out in the garbage.“

Even after his dismissal, McCabe will probably be eligible to begin collecting his pension at about age 57, although he would likely lose access to federal health coverage and would probably get a smaller pension than if he stayed on the federal payroll, experts said.

There have been claims McCabe could get hired by a member of Congress for a week so he can start drawing on it. But I’ve heard the finances aren’t even the issue, it’s the principle, which if you want to be a martyr, being fired works better.

This will have a far smaller impact on the Mueller probe than Comey-McCabe loyalists and John Dowd lay out

McCabe and others have suggested that there has been a successful effort to retaliate against Comey’s three corroborating witnesses, though that is least convincing with regards to Jim Rybicki, who was replaced as happens as a matter of course every time a new FBI Director comes in.

But the Comey-McCabe loyalists make far too much of their role in the Mueller probe, making themselves the central actors in the drama. Yes, if their credibility is hurt it does do some damage to any obstruction charges against Trump, which, as I keep repeating, will not be the primary thrust of any charges against Trump. Mueller is investigating Trump for a conspiracy with Russians; the obstruction is just the act that led to his appointment as Special Counsel and with that, a much more thorough investigation. Contrary to what you’re hearing, little we’ve seen thus far is fruit of the decisions Comey and his people made. While all were involved in the decision to charge Mike Flynn, he has already pled guilty and started spilling his guts to Mueller. There’s no reason to believe McCabe or Comey are direct witnesses in the conspiracy charges that will be filed against people close to Trump, if not against Trump himself.

For all those reasons, John Dowd’s claim that McCabe’s firing should end the investigation is equally unavailing.

I pray that Acting Attorney General Rosenstein will follow the brilliant and courageous example of the FBI Office of Professional Responsibility and Attorney General Jeff Sessions and bring an end to alleged Russia Collusion investigation manufactured by McCabe’s boss James Comey based upon a fraudulent and corrupt Dossier.

I mean, if this really is Dowd’s impression of why his client is being investigated, I almost feel sorry for Trump.

But the truth is the dossier has always been a distraction. The obstruction charge was probably used to distract Trump (and his NYT stenographers) while Mueller’s team collected the far more serious evidence on the conspiracy charges, though events of this week may well add to the conspiracy charges. And Comey didn’t manufacture any investigation; if anything, his people were not aggressive enough in the months he oversaw the investigation, particularly as it pertains to George Papadopoulos.

So if Dowd thinks McCabe’s firing will affect the core of the evidence Mueller has already developed (and, I suspect, started hanging on a sealed magnet indictment), he is likely to be very disappointed.

Regardless of the merits of the McCabe firing, it (and the related shit storm) may give Rosenstein and Mueller more time to work. It’s not clear they need that much more time to put together the conspiracy charges that are sitting right beneath the surface.

Finally — and I’m about to do a post on this — the far more important news from yesterday is that Facebook is cutting off Cambridge Analytica for violating its agreements about data use. That may well lead to some far more important changes, changes that Trump has less ability to politicize.