The WaPo Solution to the NYT Problem: Laura Poitras’ Misrepresentation of Assange’s 18th Charge

If you were the average NYT reader who is unfamiliar with the developments in the prosecution against Julian Assange, reading this excellent Laura Poitras op-ed calling for, “the Justice Department [to] immediately drop these charges and the president [to] pardon Mr. Assange,” might lead you to believe there were 17 charges under the Espionage Act and the original password cracking as the single overt act in a CFAA (hacking) charge, all of them 10 years old.

That was when the Justice Department indicted Julian Assange, the founder and publisher of WikiLeaks, with 17 counts of violating the Espionage Act, on top of one earlier count of conspiring to violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

The charges against Mr. Assange date back a decade, to when WikiLeaks, in collaboration with The Guardian, The New York Times, Der Spiegel and others, published the Iraq and Afghanistan war logs, and subsequently partnered with The Guardian to publish State Department cables. The indictment describes many activities conducted by news organizations every day, including obtaining and publishing true information of public interest, communication between a publisher and a source, and using encryption tools.

Of course, as emptywheel readers, you know that DOJ superseded the indictment against Assange in June, and with it extended the timeline on the CFAA conspiracy charge through 2015.

Even the original CFAA charge described a relationship between Assange and Manning that goes beyond what journalists do (I think I understand why DOJ charged it and may return to explain that in days ahead). But the current one credibly charges Assange in the same conspiracy to hack Stratfor that five other people have already pled guilty to, meaning the only question at trial would be whether DOJ can prove Assange entered into the conspiracy and took overt acts to further it, something they appear to have compelling proof he did.

The superseding indictment also describes Assange ordering up the hack of a WikiLeaks dissident. That’s not something anyone should be defending, and there’s good reason to believe it was not an isolated incident.

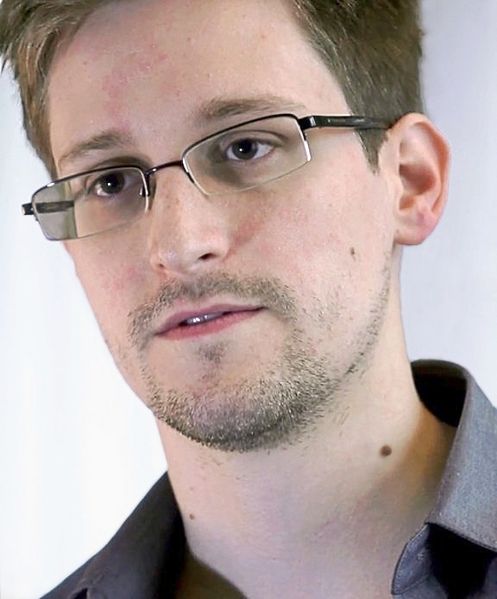

Poitras’ silence about the superseding indictment, however, is all the more striking given that it includes WikiLeaks’ efforts to help Edward Snowden to flee among the overt acts in the CFAA conspiracy. (I emailed Poitras to ask whether she even knows of the superseding indictment, which she may not, given the crappy coverage of it; I will update if she responds.)

84. To encourage leakers and hackers to provide stolen materials to WikiLeaks in the future, ASSANGE and others at WikiLeaks openly displayed their attempts to assist Snowden in evading arrest.

85. In June 2013, a WikiLeaks associate [Sarah Harrison] traveled with Snowden from Hong Kong to Moscow.

[snip]

87. At the same presentation [where Assange and Jake Appelbaum encouraged people to join the CIA to steal files, Appelbaum] said “Edward Snowden did not save himself. … Specifically for source protection, [Harrison] took actions to protect [Snowden]. … [I]f we can succeed in saving Edward Snowden’s life and to keep him free, then the next Edward Snowden will have that to look forward to. And if we look also to what has happened to Chelsea Manning, we see additionally that Snowden has clearly learned….”

[snip]

90. In an interview of May 25, 2015, ASSANGE claimed to have arranged distraction operations to assist Snowden in avoiding arrest by the United States. [listing several operations, including using “presidential jets,” suggesting that the US may have searched Evo Morales’ plane in response to disinformation spread by WikiLeaks] [bolded brackets original, other brackets my own]

With these passages, DOJ wrote the first draft of what I suspect will be expanded in the near future into a dramatically different story than the one we know about Edward Snowden (whether it will be sustainable or not is another thing). And Laura Poitras, who didn’t mention these overt acts in her op-ed, was at least adjacent to many key events in this story. For example, Poitras is likely one of the few people who would know if Snowden was in contact with Jake Appelbaum before he got a job in Hawaii and started scraping files related and unrelated to programs of concern, as Snowden himself hinted in his book. If he was, then several parts of the story that Snowden has always told are probably not true.

Similarly, Poitras’ film Risk briefly hints at tensions between Poitras and Assange over how the Snowden files would be released. That, too, suggests that WikiLeaks may have had a bigger role on the front end in Snowden’s theft of NSA documents than is publicly known.

Most importantly, at least as Bart Gellman tells it in his book, both he and Poitras were quite explicit, in the wake of requests from Snowden to help him prove his identity to obtain asylum in a foreign country, about where journalism ended and sharing classified files with foreign governments might begin.

Snowden had asked Gellman to ensure that the WaPo publish the first PRISM file with his PGP key attached. At first, Gellman hadn’t thought through why Snowden made the request. Then he figured it out.

In the Saturday night email, Snowden spelled it out. He had chosen to risk his freedom, he wrote, but he was not resigned to life in prison or worse. He preferred to set an example for “an entire class of potential whistleblowers” who might follow his lead. Ordinary citizens would not take impossible risks. They had to have some hope for a happy ending.

To effect this, I intend to apply for asylum (preferably somewhere with strong internet and press freedoms, e.g. Iceland, though the strength of the reaction will determine how choosy I can be). Given how tightly the U.S. surveils diplomatic outposts (I should know, I used to work in our U.N. spying shop), I cannot risk this until you have already gone to press, as it would immediately tip our hand. It would also be futile without proof of my claims—they’d have me committed—and I have no desire to provide raw source material to a foreign government. Post publication, the source document and cryptographic signature will allow me to immediately substantiate both the truth of my claim and the danger I am in without having to give anything up. . . . Give me the bottom line: when do you expect to go to print?

Alarm gave way to vertigo. I forced myself to reread the passage slowly. Snowden planned to seek the protection of a foreign government. He would canvass diplomatic posts on an island under Chinese sovereign control. He might not have very good choices. The signature’s purpose, its only purpose, was to help him through the gates.

How could I have missed this? Poitras and I did not need the signature to know who sent us the PRISM file. Snowden wanted to prove his role in the story to someone else. That thought had never occurred to me. Confidential sources, in my experience, did not implicate themselves—irrevocably, mathematically—in a classified leak. As soon as Snowden laid it out, the strategic logic was obvious. If we did as he asked, Snowden could demonstrate that our copy of the NSA document came from him. His plea for asylum would assert a “well-founded fear of being persecuted” for an act of political dissent. The U.S. government would maintain that Snowden’s actions were criminal, not political. Under international law each nation could make that judgment for itself. The fulcrum of Snowden’s entire plan was the signature file, a few hundred characters of cryptographic text, about the length of this paragraph. And I was the one he expected to place it online for his use.

Idiot. Remember “chain of custody”? He came right out and told you he wanted a historical record.

My mind raced. When Snowden walked into a consulate, evidence of his identity in hand, any intelligence officer would surmise that he might have other classified information in reach. Snowden said he did not want to hand over documents, but his language, as I read it that night, seemed equivocal. Even assuming he divulged nothing, I had not signed up for his plan. I had agreed to protect my source’s identity in order to report a story to the public. He wanted me to help him disclose it, in private, as a credential to present to foreign governments. That was something altogether different.

Gellman realized — and Poitras seemed to agree in texts Gellman published in the book — that this request might amount to abetting Snowden’s sharing of secrets with a hostile government.

LP: oh god fuck

BG: He’s in a position to provide that material. He may be under compulsion. We REALLY can’t do anything that could abet or be perceived to abet that.

LP: of course

BG: I just wanna be a goddam journalist

Gellman and Poitras discussed the request with the lawyers WaPo consulted regarding the Snowden publications. In what might be the chilling consultation with a First Amendment lawyer that Poitras describes in her oped, one lawyer seems to have raised concerns about aiding and abetting charges, and had them both write explicit notes to Snowden denying his request to publish his key. In those notes, as published by Gellman, both drew a bright line between what they considered journalistic — protecting his identity and publishing the newsworthy files while balancing risk — and what was not.

Everyone on the call agreed that we would carry on with our story plans and protect the source’s identity as before. No one but Poitras and I knew Snowden’s name anyway. But Kevin Baine, the lead outside counsel, asked me in a no-bullshit tone to level with him. Had I ever promised to publish the full PRISM presentation or its digital signature? I had not, and Poitras said the same. Our source framed both those points as “requests” before he sent the document. Poitras and I had ducked and changed the subject. Why engage him in a hypothetical dispute? Depending on what the document said, publication in full might have been an easy yes. “You have to tell him you never agreed to that,” Baine said. Poitras and I faced a whole new kind of legal exposure now. We could not leave unanswered a “direct attempt to enlist you in assisting him with his plans to approach foreign governments.”

[snip]

We hated the replies we sent to Snowden on May 26. We had lawyered up and it showed. “You were clear with me and I want to be equally clear with you,” I wrote. “There are a number of unwarranted assumptions in your email. My intentions and objectives are purely journalistic, and I will not tie them or time them to any other goal.” I was working hard and intended to publish, but “I cannot give you the bottom line you want.”

Poitras wrote to him separately.

There have been several developments since Monday (e.g., your decision to leave the country, your choice of location, possible intentions re asylum), that have come as a surprise and make [it] necessary to be clear. As B explained, our intentions and objectives are journalistic. I believe you know my interest and commitment to this subject. B’s work on the topic speaks for itself. I cannot travel to interview you in person. However, I do have questions if you are still willing to answer them. [my emphasis]

If Assange (or anyone associated with him) is ever tried on the superseding indictment, I’d be surprised if these passages weren’t introduced at trial. Here you have two of the key journalists who published the Snowden files, laying out precisely where WikiLeaks fails the NYT problem that DOJ, under Obama, could never get past in any prosecution of Julian Assange.

“The problem the department has always had in investigating Julian Assange is there is no way to prosecute him for publishing information without the same theory being applied to journalists,” said former Justice Department spokesman Matthew Miller told the Post. “And if you are not going to prosecute journalists for publishing classified information, which the department is not, then there is no way to prosecute Assange.”

In 2013, before the first Snowden files got published, Gellman and Poitras and the Washington Post solved the New York Times problem. Helping Snowden flee to a foreign country — which, given Snowden’s plan to meet them in Hong Kong, they assumed might include to an adversarial nation like China — was not journalistic and, seemingly even according to the journalists, might be abetting Snowden’s sharing of files with a hostile foreign government.

Which is why Poitras’ silence about these charges in her bid to dismiss the charges against Assange undermines her argument.

Again, I absolutely agree with Poitras that the Espionage charges, as charged, pose a real risk to journalism. But the government is going to use the CFAA charge to explain how Assange’s methods are different from journalists. And Poitras’ own actions may well be part of that proof.