When I saw the news that Trump is planning a rally at Madison Square Garden — as the Nazis did in 1939 — I checked the date to see whether that was before or after Steve Bannon gets out of prison.

Bannon is due to get out on October 29; the rally is two days earlier, on October 27. On the current schedule, Bannon will be released nine days before the election, but not soon enough to attend what will undoubtedly be a larger version of the Nazi rant that Trump put on in Aurora the other day. Unless something disrupts it, Bannon will start trial for defrauding Trump supporters on December 9, days before the states certify the electoral vote.

This is the kind of timing I can’t get out of my head. According to FiveThirtyEight, Kamala Harris currently has a 53% chance of winning the electoral college. That’s bleak enough. But based on everything I know about January 6, I’d say that if Trump loses, there’s at least a 10% chance Trump’s fuckery in response will have a major impact on the transfer of power.

Experts on right wing extremism are suggesting the same thing. Here’s an interview Rick Perlstein did with David Neiwert back in August on the political violence he expects. Here’s a report from someone who infiltrated the 3 Percenters, predicting they would engage in vigilanteism.

Will Jack Smith unveil charges about inciting violence amid election violence?

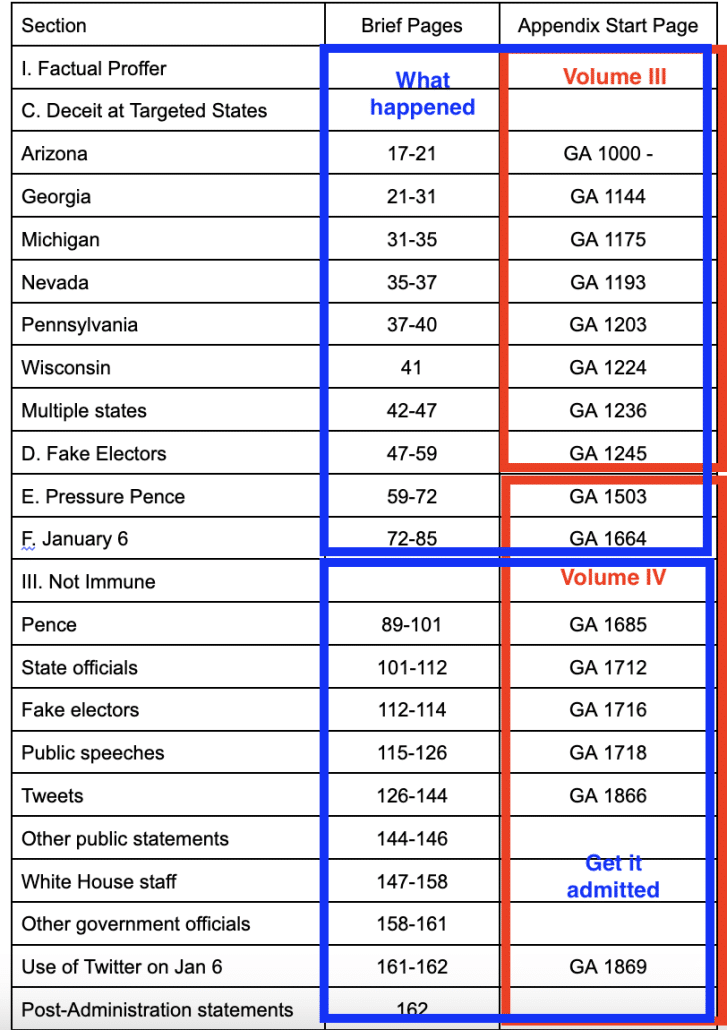

As I wrote in this post, I suspect that Jack Smith considered, but did not, add charges when he decided to supersede Trump’s January 6 indictment. As I wrote, there is negative space in Smith’s immunity filing where charges on Trump’s funding for January 6 (and subsequent suspected misuse of those funds) might otherwise be.

More tellingly, there are four things that indicate Jack Smith envisioned — but did not yet include — charges relating to ginning up violence. As Smith did in a 404(b) filing submitted in December, he treated Mike Roman as a co-conspirator when he exhorted a colleague, “Make them riot” and “Do it!!!” Newly in the immunity filing, he treated Bannon as a co-conspirator, providing a way to introduce Steve Bannon’s prediction, “All Hell is going to break loose tomorrow!” shortly after speaking with Trump on January 5. But Smith didn’t revise the indictment to describe Roman and Bannon as CC7 and CC8; that is, he did not formally include these efforts to gin up violence in this indictment. What appears to be the same source for the Mike Roman detail (which could be Roman’s phone, which was seized in September 2022; in several cases it has taken a year to exploit phones seized in the January 6 investigation) also described that Trump adopted the same tactic in Philadelphia.

The defendant’s Campaign operatives and supporters used similar tactics at other tabulation centers, including in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,21 and the defendant sometimes used the resulting confrontations to falsely claim that his election observers were being denied proper access, thus serving as a predicate to the defendant’s claim that fraud must have occurred in the observers’ absence.22

Even more notably, after saying (in that same December 404(b) filing) that he wanted to include Trump’s endorsement and later ratification of the Proud Boys’ attack on the country to “demonstrate[] the defendant’s encouragement of violence,” Smith didn’t include them in the immunity filing whatsoever — not even in the section where the immunity filing described Trump’s endorsement of men who assaulted cops. If I’m right that Smith held stuff back because SCOTUS delayed his work so long it butted into the election season, it would mean he believes he has the ability to prove that Trump deliberately stoked violence targeting efforts to count the vote at both the state and federal level, but could not lay that out until after November 5, after which Trump may be in a position to dismiss the case entirely.

And the two Stephens — Bannon, whose War Room podcast would serve to show that Trump intended to loose all Hell on January 6, and Miller, who added the finishing touches to Trump’s speech making Mike Pence a target for that violence — appear to have a plan to do just that, working in concert with Elon Musk.

The two Stephens say Trump must be able to stoke violence with false claims as part of his campaign

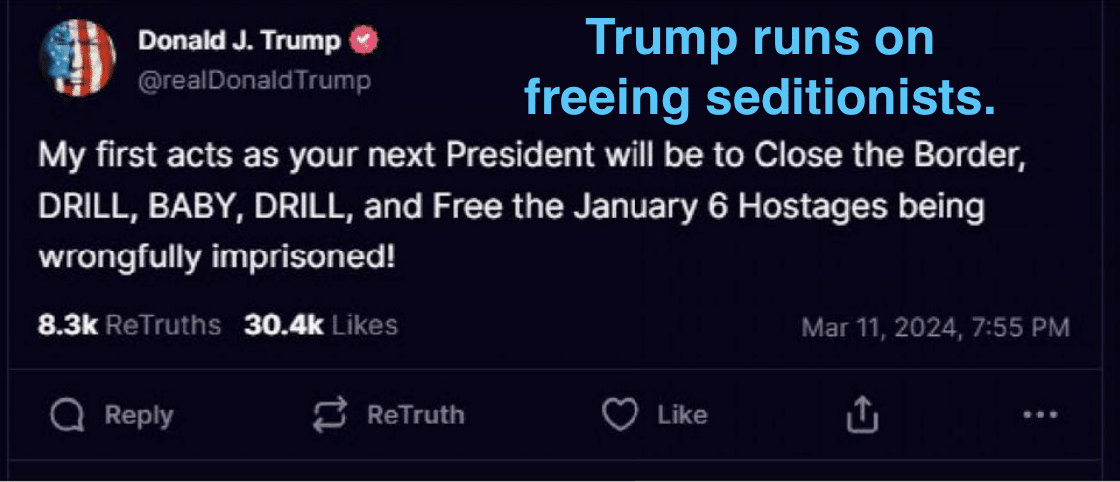

As I laid out in June, just as Bannon was reporting to prison, both Stephens were arguing that they had a right to make false claims that had the effect of fostering violence.

Bannon filed an emergency appeal aiming to stay out of prison arguing he had to remain out so he could “speak[] on important issues.”

There is also a strong public interest in Mr. Bannon remaining free during the run-up to the 2024 presidential election. The government seeks to imprison him for the four-month period immediately preceding the November election—giving an appearance that the government is trying to prevent Mr. Bannon from fully assisting with the campaign and speaking out on important issues, and also ensuring the government exacts its pound of flesh before the possible end of the Biden Administration.

No one can dispute that Mr. Bannon remains a significant figure. He is a top advisor to the President Trump campaign, and millions of Americans look to him for information on matters important to the ongoing presidential campaign. Yet from prison, Mr. Bannon’s ability to participate in the campaign and comment on important matters of policy would be drastically curtailed, if not eliminated. There is no reason to force that outcome in a case that presents substantial legal issues.

That claim came just after he had given a “Victory or Death” speech at a Turning Point conference.

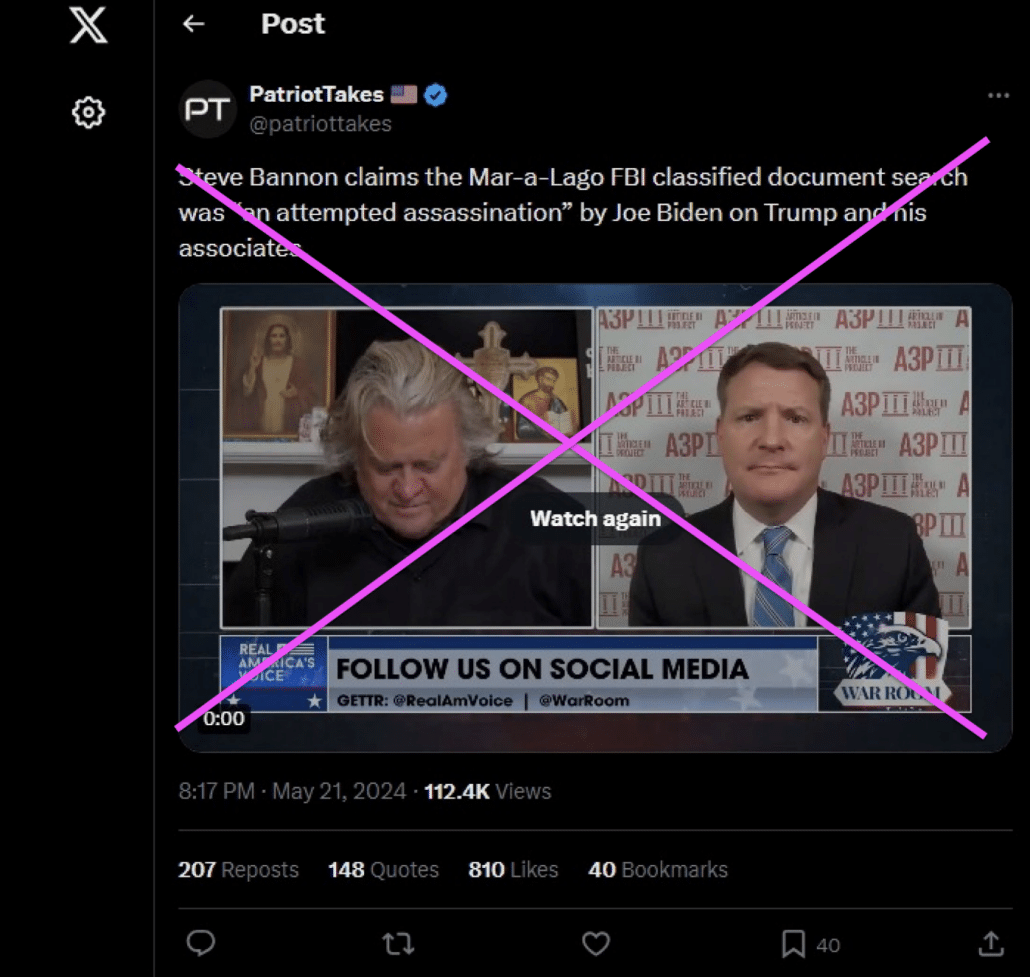

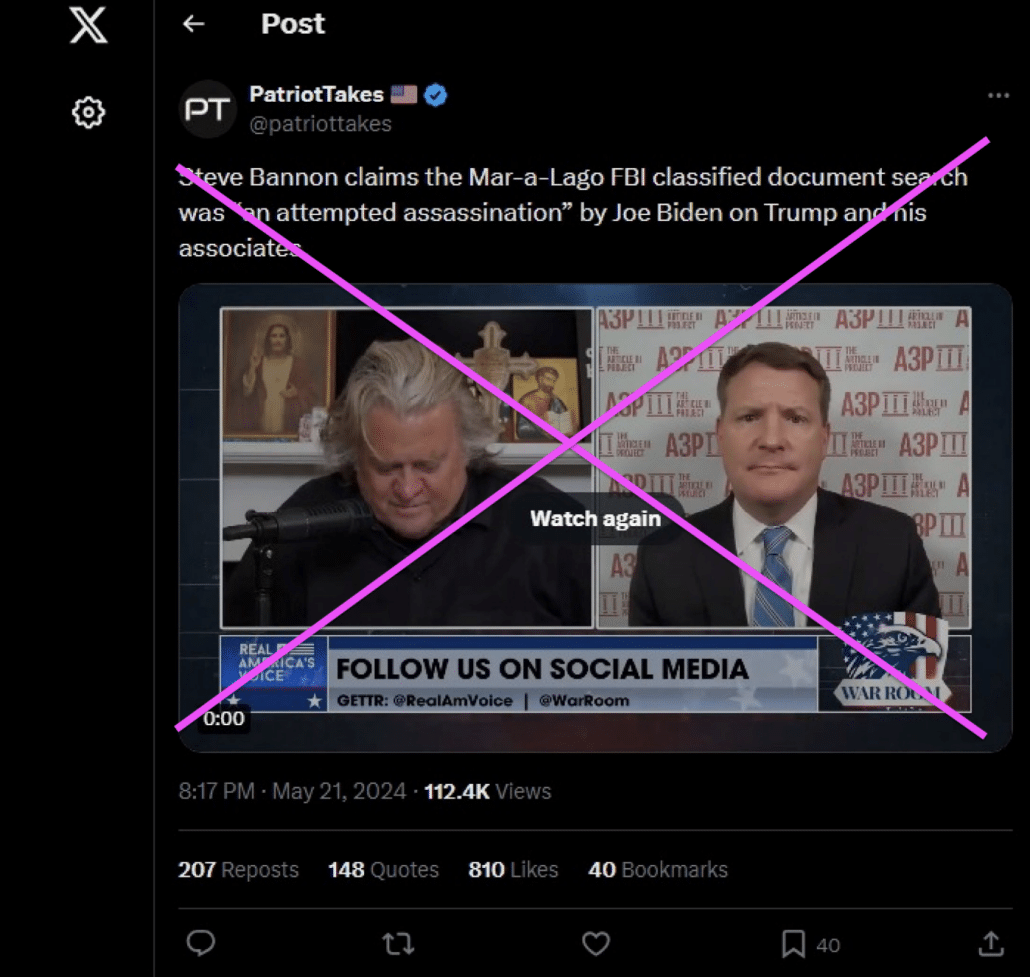

In the same period, Stephen Miller attempted to intervene in Jack Smith’s efforts to prevent Trump from making false claims that the FBI tried to assassinate him when they did a search of his home governed by a standard use-of-force policy, knowing full well he was gone. (Aileen Cannon rejected Miller’s effort before she dismissed the case entirely.)

Miller argued that the type of speech that Smith wanted to limit — false claims that have already inspired a violent attack on the FBI — as speech central to Trump’s campaign for President.

The Supreme Court has accordingly treated political speech—discussion on the topics of government and civil life—as a foundational area of protection. This principle, above all else, is the “fixed star in our constitutional constellation[:] that no official, high or petty, can prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics[ or] nationalism . . . or force citizens to confess by word or act their faith therein.” W. Va. State Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 642 (1943) (Jackson, J.). Therefore, “[d]iscussion of public issues and debate on the qualifications of candidates” are considered “integral” to the functioning of our way of government and are afforded the “broadest protection.” Buckley, 424 U.S. at 14.

Because “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open” debate enables “the citizenry to make informed choices among candidates for office,” “the constitutional guarantee has its fullest and most urgent application precisely to the conduct of campaigns for political office.” Id. at 14-15 (citations omitted). Within this core protection for political discourse, the candidates’ own speech—undoubtedly the purest source of information for the voter about that candidate—must take even further primacy. Cf. Eu v. S.F. Cnty. Democratic Cent. Comm., 489 U.S. 214, 222-24 (1989) (explaining that political speech by political parties is especially favored). This must be especially true when, as here, the candidate engages in a “pure form of expression involving free speech alone rather than expression mixed with particular conduct.” Buckley, 424 U.S. at 17 (cleaned up) (contrasting picketing and parading with newspaper comments or telegrams). These principles layer together to strongly shield candidates for national office from restrictions on their speech.

Miller called Trump’s false attack on the FBI peaceful political discourse.

Importantly, Miller dodged an argument Smith made — that Trump intended that his false claims would go viral. He intended for people like Bannon to repeat his false claims. In disclaiming any intent to incite imminent action, Miller ignored the exhibit showing Bannon parroting Trump’s false claim on his War Room podcast.

It cannot be said that by merely criticizing—or, even as some may argue, mischaracterizing—the government’s actions and intentions in executing a search warrant at his residence, President Trump is advocating for violence or lawlessness, let alone inciting imminent action. The government’s own exhibits prove the point. See generally ECF Nos. 592-1, 592-2. 592-3, 592-5.

Note, Bannon did this with Mike Davis, a leading candidate for a senior DOJ position under Trump, possibly even Attorney General, who has vowed to instill a reign of terror in that position.

But that was the point — Jack Smith argued — of including an exhibit showing Bannon doing just that.

Predictably and as he certainly intended, others have amplified Trump’s misleading statements, falsely characterizing the inclusion of the entirely standard use-of-force policy as an effort to “assassinate” Trump. See Exhibit 4.

Back in June, Bannon said he had to remain out of prison because he played a key role in Trump’s campaign. And Miller said that even if Bannon deliberately parroted Trump’s false incendiary claims, that was protected political speech as part of Trump’s campaign.

Miller helps eliminate checks on disinformation and Nazis on Xitter

But this effort has been going on for years.

A report that American Sunlight released this week describing how systematically the right wing turned to dismantling the moderation processes set up in the wake of the 2016 election points to Miller’s America First Legal’s role in spinning moderation by private actors as censorship. Miller started fundraising for his effort in 2021.

[F]ormer Trump Senior Advisor Stephen Miller[] founded America First Legal (AFL). 6 An unflinchingly partisan organization, the home page of AFL’s website claims its mission is to “[fight] back against lawless executive actions and the Radical Left,” 7 which it accomplishes through litigation. AFL has, to date, engaged in dozens of efforts to silence disinformation research through frivolous lawsuits and collaboration with Jordan and the House Judiciary Committee’s harassment of researchers. In a digital age where social media is more prevalent than ever and social media platforms have more power than ever, AFL’s efforts to politicize legitimate efforts to combat disinformation – by social media platforms and independent private-citizen researchers – have significantly damaged the information environment. To fully realize these efforts and their impacts, we explore the founding and operations of AFL.

[snip]

After its launch in early 2022, AFL began its line of litigation with a series of FOIA requests relating to the State Department’s Global Engagement Center (GEC) and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). These requests marked a noticeable uptick in conservative claims about censorship. AFL’s FOIA requests alleged these government agencies improperly partnered with social media platforms and asked for content around Hunter Biden’s laptop to be removed. 22 In its FOIA request to CISA, AFL writes 23 :

On March 17, 2022, the New York Times revealed that “[Hunter] Biden’s laptop was indeed authentic, more than a year after … much of the media dismissed the New York Post’s reporting as Russian disinformation.” When the story was first accused of being disinformation, X/Twitter suspended the New York Post’s account for seven days, and Facebook “’reduc[ed]’ the story’s distribution on its platform while waiting for third-party fact checkers to verify it.” This was just one of many instances where social media companies censored politically controversial information under the pretext of combatting MDM even when the information later became verified.

Then, as now, AFL offered no evidence to support its claim that any federal agency coerced, pressured, or mandated that social media platforms remove any such laptop-related content. As this report will cover in depth, social media platforms have their own, robust content moderation policies in regards to false and misleading content; as private companies, they implement these policies as they see fit.

The American Sunlight report describes how some of the key donations to AFL were laundered so as to hide the original donors (and other of its donations came from entities that had received the funds Trump raised in advance of January 6).

But as WSJ recently reported, Musk started dumping tens of millions into Miller’s racist and transphobic ads no later than June 2022.

In the fall of 2022, more than $50 million of Musk’s money funded a series of advertising campaigns by a group called Citizens for Sanity, according to people familiar with his involvement and tax filings for the group. The bulk of the ads ran in battleground states days before the midterm elections and attacked Democrats on controversial issues such as medical care for transgender children and illegal immigration.

Citizens for Sanity was incorporated in Delaware in June 2022, with salaried employees from Miller’s nonprofit legal group listed as its directors and officers.

There are questions of whether Miller grew close to Musk even before that.

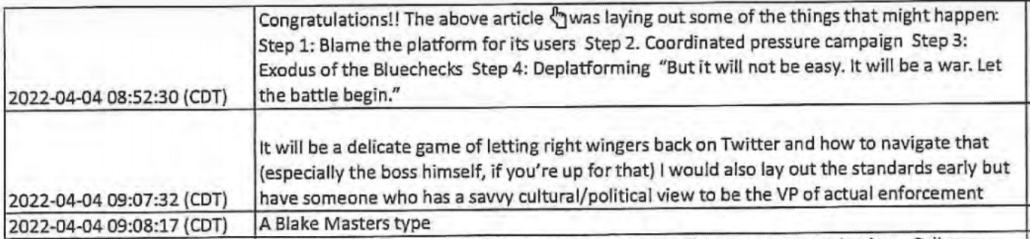

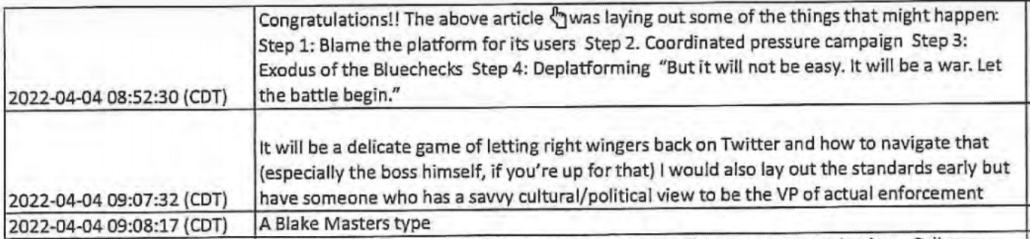

In the lead-up to Musk’s purchase of Xitter, someone — there’s reason to believe it might be Stephen Miller — texted Musk personally to raise the sensitivities of restoring Trump, whom the person called, “the boss,” to Xitter.

And one of Musk’s phone contacts appears to bring Trump up. However, unlike others in the filings, this individual’s information is redacted.

“It will be a delicate game of letting right wingers back on Twitter and how to navigate that (especially the boss himself, if you’re up for that),” the sender texted to Musk, referencing conservative personalities who have been banned for violating Twitter’s rules.

Whoever this was — and people were guessing it was Miller in real time — someone close enough to Elon to influence his purchase of Xitter was thinking of the purchase in terms of bringing back “right wingers,” including Trump.

Yesterday, the NYT reported on how the far right accounts that Musk brought back from bannings have enjoyed expanded reach since being reinstated. Some of the most popular accounts have laid the groundwork for attacking the election.

As the election nears, some of the high-profile reinstated accounts have begun to pre-emptively cast doubt on the results. Much of the commentary is reminiscent of the conspiracy theories that swirled after the 2020 election and in the lead-up to the Jan. 6 riot.

Since being welcomed back to the platform, roughly 80 percent of the accounts have discussed the idea of stolen elections, with most making some variation of the claim that Democrats were engaged in questionable voting schemes. Across at least 1,800 posts on the subject, the users drew more than 13 million likes, shares and other reactions.

Some prominent accounts shared a misleading video linked to the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank, that used shaky evidence to claim widespread voter registration of noncitizens. One of the posts received more than 750,000 views; Mr. Musk later circulated the video himself.

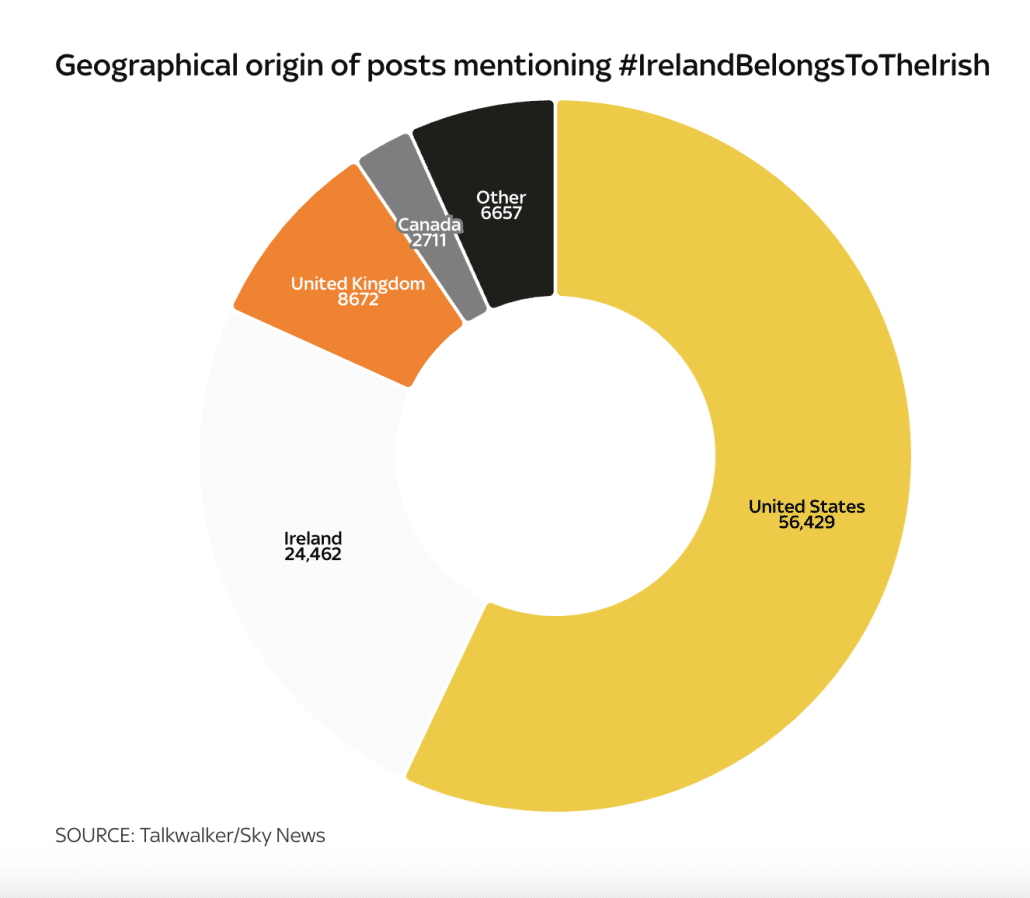

But it’s more than just disinformation. Xitter has played a key role in stoking anti-migrant violence across the world. In Ireland, for example, Alex Jones’ magnification of Tommy Robinson’s tweets helped stoke an attack on a shelter for migrants.

As with mentions of Newtownmountkennedy, users outside of Ireland authored the most posts on X mentioning this hashtag, according to the data obtained by Sky News. 57% were posted by accounts based in the United States, 24.7% by Irish users. A further 8.8% were attributed to users based in the United Kingdom.

While four of the top five accounts attracting the most engagement on posts mentioning this hashtag were based in Ireland, the fifth belongs to Alex Jones, an American media personality and conspiracy theorist. Jones’s posts using this hashtag were engaged with 10,700 times.

Jones continued to platform Robinson as he stoked riots in the UK.

Several high-profile characters known for their far-right views have provided vocal commentary on social media in recent days and have been condemned by the government for aggravating tensions via their posts.

Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, who operates under the alias Tommy Robinson, has long been one of Britain’s most foremost far-right and anti-Muslim activists and founded the now-defunct English Defence League (EDL) in 2009.

According to the Daily Mail, Robinson is currently in a hotel in Cyprus, from where he has been posting a flurry of videos to social media. Each post has been viewed hundreds of thousands of times, and shared by right-wing figures across the world including United States InfoWars founder Alex Jones.

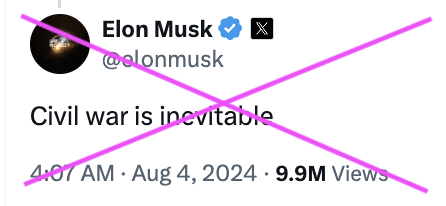

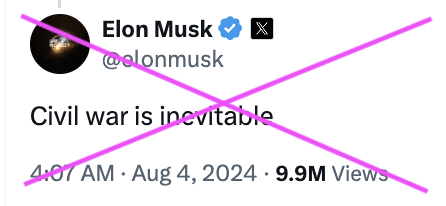

And Elon Musk himself famously helped stoke the violence, not just declaring civil war to be “inevitable,” but also adopting Nigel Farage’s attacks on Keir Starmer.

On Monday, a spokesperson for UK Prime Minister Keir Starmer addressed Musk’s comment, telling reporters “there’s no justification for that.”

But Musk is digging his heels in. On Tuesday, he labeled Starmer #TwoTierKier in an apparent reference to a debunked claim spread by conspiracy theorists and populist politicians such as Nigel Farage that “two-tier policing” means right-wing protests are dealt with more forcefully than those organized by the left. He also likened Britain to the Soviet Union for attempting to restrict offensive speech on social media.

In the UK, such incitement is illegal. But it is virtually impossible to prosecute in the United States. So if Elon ever deliberately stoked political violence in the US, it would be extremely difficult to stop him, even ignoring the years of propaganda about censorship and the critical role some of Musk’s companies play in US national security.

Bannon’s international fascist network

The ties to Nigel Farage go further than Xitter networks.

In a pre-prison interview with David Brooks (in which Brooks didn’t mention how Bannon stands accused of defrauding Trump’s supporters in his New York case), Bannon bragged about turning international fascists into rocks stars.

STEVE BANNON: Well, I think it’s very simple: that the ruling elites of the West lost confidence in themselves. The elites have lost their faith in their countries. They’ve lost faith in the Westphalian system, the nation-state. They are more and more detached from the lived experience of their people.

On our show “War Room,” I probably spend at least 20 percent of our time talking about international elements in our movement. So we’ve made Nigel a rock star, Giorgia Meloni a rock star. Marine Le Pen is a rock star. Geert is a rock star. We talk about these people all the time.

And in August, Bannon’s top aide, Alexandra Preate, registered as a foreign agent for Nigel Farage. She cited arranging his participation in:

- A March 2023 CPAC speech

- Discussions, as early as August 2023, about a Farage speech at RNC

- A January 2024 pitch for Farage to speak at a Liberty University CEO Summit that was held last month

- Talks at “Sovereignty Summits” in April through July

- April arrangements for a May 1 talk at Stovall House in Tampa, Florida

- Discussions in May about addressing CPAC in September

- May 2024 media appearances on the Charlie Kirk Show, Fox Business Larry Kudlow show, Bannon’s War Room, Seb Gorka Show, Newsmax, WABC radio

- More discussions about Farage’s attendance at the RNC

- Early August discussions about an upcoming trip to the US

That is, Preate retroactively registered as Farage’s agent after a period (July to August) when he was spreading false claims that stoked riots in his own country.

Preate also updated her registration for the authoritarian Salvadoran President, Nayib Bukele (which makes you wonder whether she had a role in this fawning profile of Bukele).

Miller serves as opening act for Trump’s Operation Aurora

Before Trump’s speech in Aurora, CO the other day — at which he spoke of using the Alien and Sedition Act against what he deemed to be migrants — Stephen Miller served as his opening act, using the mug shots of three undocumented immigrants who have committed violent crimes against American women to rile up the crowd, part of a years-long campaign to falsely suggest that migrants are even as corrupt as violent as white supremacists.

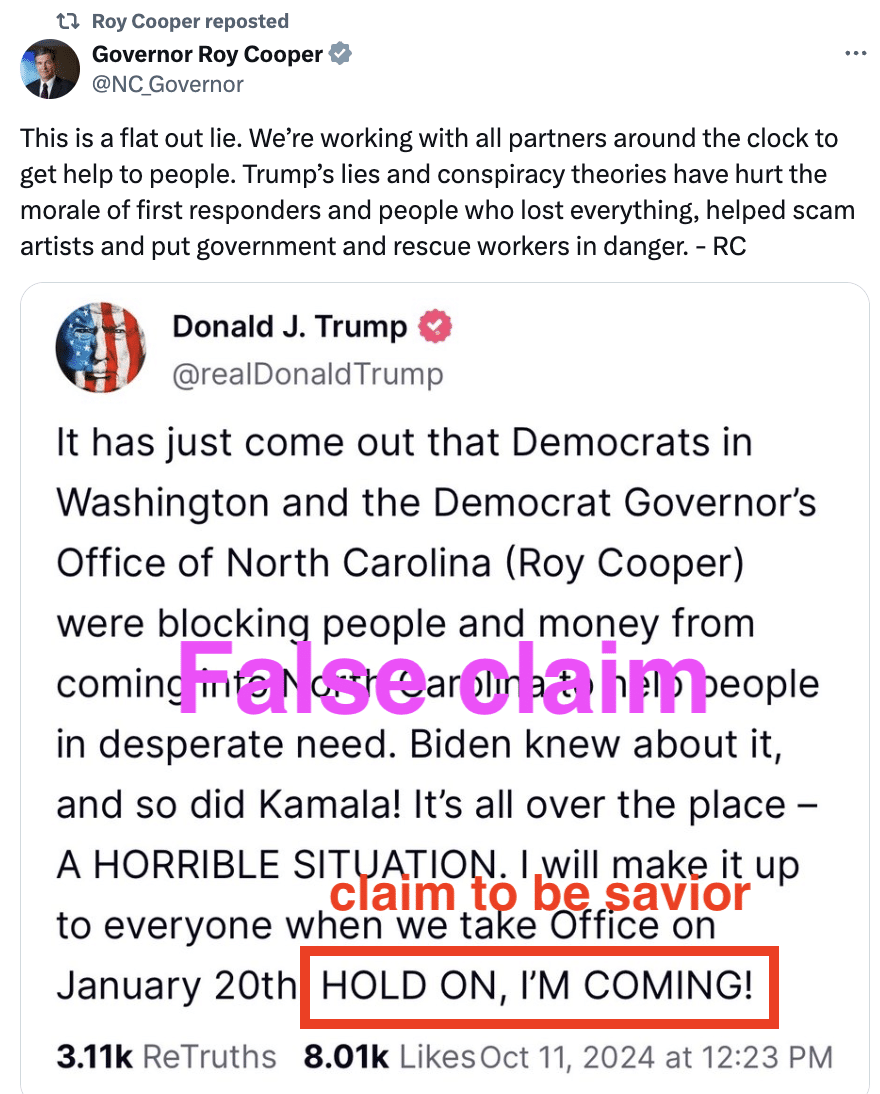

Stephen Miller started laying the infrastructure to improve on January 6 from shortly after the failed coup attempt (and he did so, according to the American Sunlight report, with funds that Trump may have raised with his Big Lie). In recent weeks, Trump — with Miller’s help — has undermined the success of towns in Ohio and Colorado with racial division and has led his own supporters hard hit by hurricanes to forgo aid to which they’re entitled with false claims that Democrats are withholding that aid.

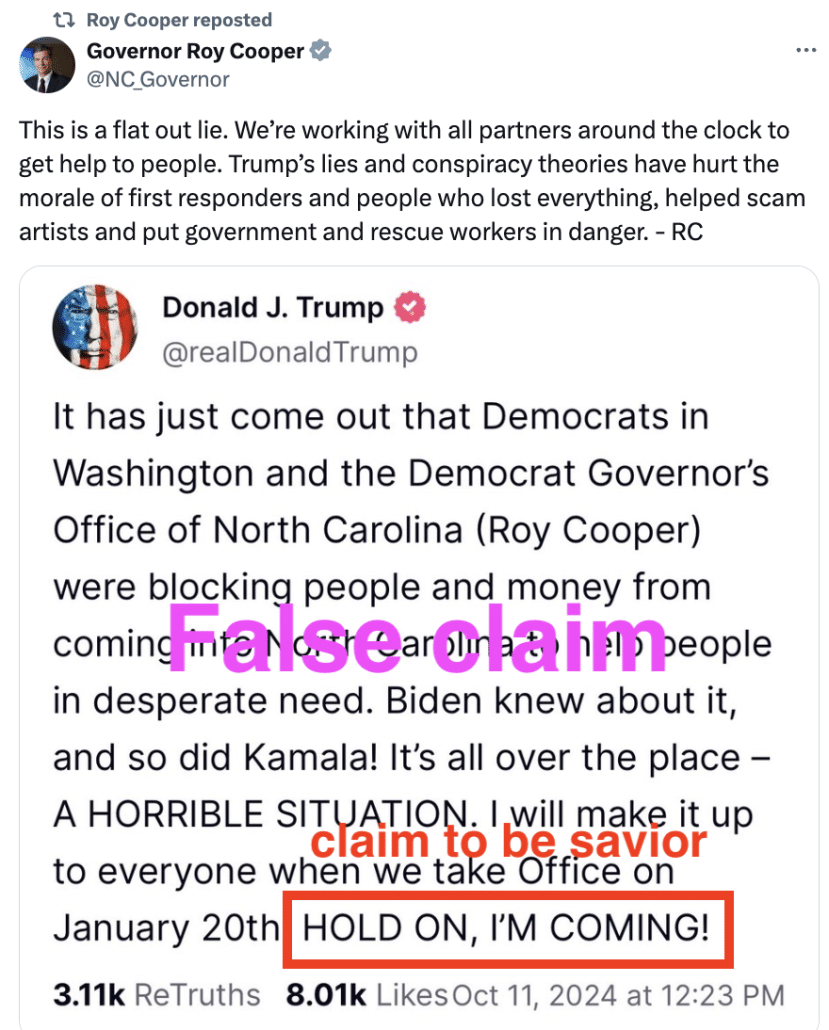

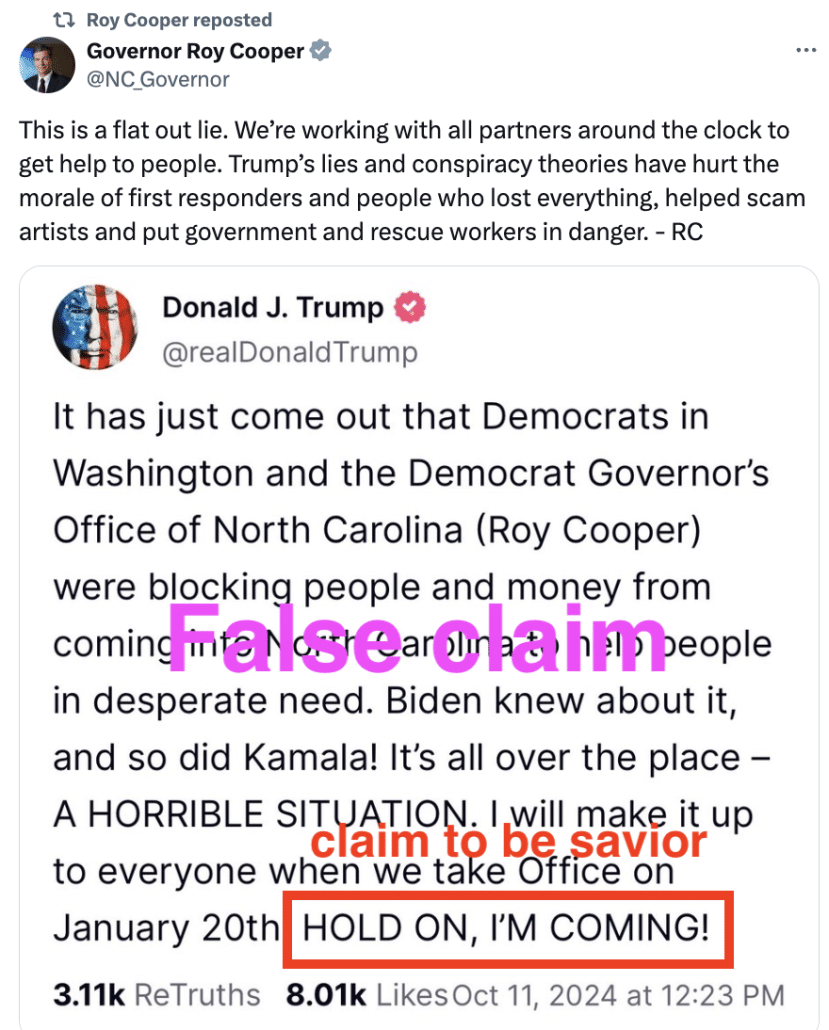

By targeting people like North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper and Kamala Harris, Trump is targeting not just Democrats, but also people who play a key role in certifying the election.

If Cooper and Harris were incapacitated before they played their role in certifying the election, they would be replaced by Mark Robinson and whatever president pro tempore a Senate that is expected to have a GOP majority after January 4 chooses, if such a choice could be negotiated in a close Senate in a few days.

And all the while, the richest man in the world, who claims that he, like Steve Bannon and Donald Trump, might face prison if Vice President Harris wins the election, keeps joking about assassination attempts targeting Harris.

We have just over three weeks to try to affect the outcome on November 5 — to try to make it clear that Trump will do for America what he has done in Springfield, Aurora, and Western North Carolina, deliberately made things worse for his own personal benefit. But at the same time, we need to be aware of how those efforts to make things worse are about creating a problem that Trump can demand emergency powers to solve.