Levitation: Inspire-Ing Work from CSE

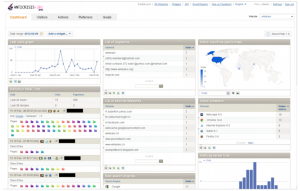

The Intercept and CBC have a joint story on a Canadian Security Establishment project called Levitation that seems to confirm suspicions I’ve had since before the Snowden leaks. It targets people based on their web behavior (the story focuses on downloads from free file upload sites, but one page of the PPT makes it clear they’re also tracking web search terms and other behaviors), and once it finds behavior of suspicion (such as accessing bomb-making instructions; it calls these “events”) it uses SIGINT tools, including NSA’s MARINA, to work backwards off those accessing those materials to get IPs, cookies, facebook IDs, and the like to identify a suspect.

The Intercept and CBC have a joint story on a Canadian Security Establishment project called Levitation that seems to confirm suspicions I’ve had since before the Snowden leaks. It targets people based on their web behavior (the story focuses on downloads from free file upload sites, but one page of the PPT makes it clear they’re also tracking web search terms and other behaviors), and once it finds behavior of suspicion (such as accessing bomb-making instructions; it calls these “events”) it uses SIGINT tools, including NSA’s MARINA, to work backwards off those accessing those materials to get IPs, cookies, facebook IDs, and the like to identify a suspect.

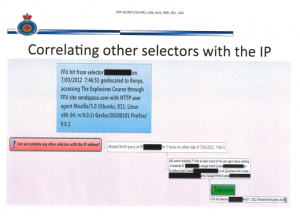

The PPT is the most detailed explanation that I’ve seen of how the SIGINT agencies do “correlations” — a function about which I believe ODNI continues to hide an August 20, 2008 FISC opinion. It appears to do so in two ways: first, by tracking known correlations. But also, by analyzing similar activities from around the same time from the same IP, then coming up with other identifiers that, with varying degrees of probability, are probably the same user. This serves, in part, to come up with new identifiers to track.

I’ve argued the NSA does similar analysis using known codes tied to Inspire (not the URL, necessarily, but possibly the encryption code included in each Inspire edition) on upstream collection, which would basically identify the people within the US who had downloaded AQAP’s propaganda magazine. One reason I’m so confident NSA does this is because of the high number of FBI sting operations that seem to arise from some 20-year old downloading Inspire, which them appears to get sent out to a local FBI office for further research into online activities and ultimately approaches by a paid informant or undercover officer.

In other words, this kind of analysis seems to lie at the heart of a lot of the stings FBI initiates.

In other words, this kind of analysis seems to lie at the heart of a lot of the stings FBI initiates.

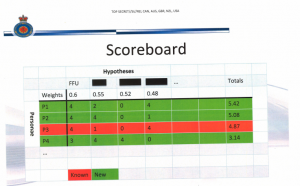

But as the “Scoreboard” slide in this presentation makes clear, what this process gives you is not validated IDs, but rather probabilistic matches (which FISC appears to deal with using minimization procedures, suggesting they let NSA collect on these probabilistic matches with the understanding they have to treat the data in some certain way if it ends up being a false positive).

That’s important not just for the young men whom FBI decides might make worthwhile targets (even if they’re being targeted, largely, on their First Amendment activities).

It’s important, too, for the false negatives, by far the most important of which I believe to be the Tsarnaev brothers, both of whom reportedly had downloaded multiple episodes of Inspire, as well as other similar jihadist material, and on whom NSA had collected data it never accessed until after the attack, but neither of whom got targeted off this correlation process before they attacked the Boston Marathon.

That is, this really important possible false negative, just as much as the dubious positives that end up getting unbalanced young men targeted by the FBI, may say as much about the reliability of this process as anything else.

This CSE PPT is not yet proof that my suspicions are entirely accurate (though my claims here about correlations are based on officially released documents). But they strongly suggest my suspicions have been correct.

And — particularly given ODNI’s refusal to release what appears to be a key opinion describing the terms on which FISC permits the use of these correlations — this ought to elicit far more conversations about how NSA and its Five Eye partners “correlate” identities and how those correlations get used.