Enough With Hobbes And Rousseau

Introduction and Index. This post is updated with other stuff I think is interesting.

The Dawn Of Everything by David Graeber and David Wengrow asks us to think about whether our society is the culmination of the development of human societies, and whether it’s the only one that can possibly work in a technological age.

In Chapter 1 they tell us that they initially set out to contribute to the growing debate about inequality by examining advances in archaeology and anthropology to see what they tell us about the origins of inequality. They concluded that this was not a good plan.

They start by explaining the prevailing view of the the history of human societies. One is that of Thomas Hobbes, set out his his book Leviathan, written in 1651. The other comes from Jean-Jacques Rousseau in an essay, Discourse on the Origin and the Foundation of Inequality Among Mankind, written in 1754.

Hobbes seems to start with the proposition that humans are basically selfish and brutish, and argues that we can only live decently under an authoritarian system. Rousseau seems to start with the proposition that humans were once good but have fallen from grace, a secular version of the story told by Christian Bible’s Book of Genesis. Rousseau then offers the progression of human society from foragers to bands to tribes to cities to states.

Both of these writings are speculations, thought experiments, or personal prejudices, utterly without evidentiary support. Hobbes was writing during the English Civil War, a serious crisis that the authors suggest influenced his view that humans are aggressive jerks. Rousseau wrote his essay for entry in a contest with a cash prize. It was meant not as an historical account but as a thought experiment, a speculative account. The question was set because the issue became salient in part through what the authors call the “indigenous critique” which they take up in detail in Chapter 2.

As the reader can probably detect from our tone, we don’t much like the choice between these two alternatives. Our objections can be classified into three broad categories. As accounts of the general course of human history, they:

1. simply aren’t true;

2. have dire political implications;

3. make the past needlessly dull.

This book is an attempt to begin to tell another, more hopeful and more interesting story; one which, at the same time, takes better account of what the last few decades of research have taught us. P. 3.

The first point is a major thread of the book. As to the second, on the Hobbesian view the best we can hope for is an authoritarian government with power to force decent behavior as defined by the Leader. Rousseau’s fall from grace theory says that we’re stuck, and can’t hope for much change. With respect to out-of-control inequality, either view means we aren’t going to get any change that the rich don’t like.

In the discussion of these first two points, we are introduced to some of the main themes that recur throughout the book.

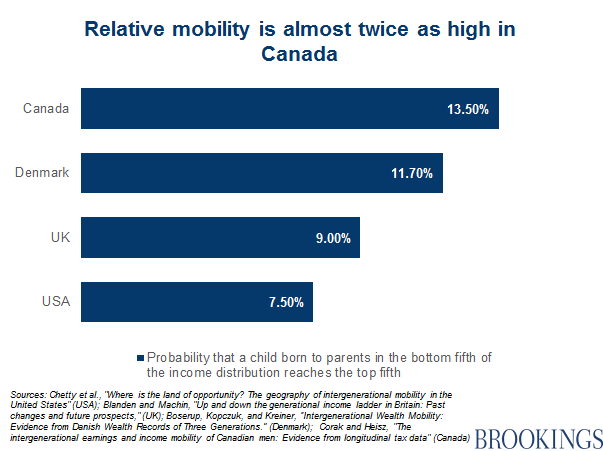

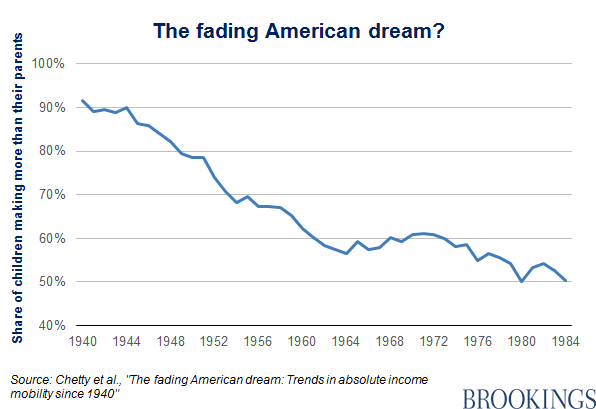

1. It’s only in the last 300 years that Western thinkers have considered inequality a serious problem. Before that time, almost everyone just accepted rigid class structures as the will of the Almighty. It’s telling that the most common meaning of the term is economic inequality. We rarely discuss the other inequalities that beset our society such as power, participation in decision-making, the right to have one’s interests considered in decision-making, and the way these are distributed by race, sex, creed and class to name some of the obvious.

2. Some people can and do convert material wealth into political power, or as the authors sometimes put it, the power to push other people around.

3. The quality of life in modern civilization isn’t all that great. We get our first taste of this argument, as the authors ask whether Western civilization actually made life better for everyone. Here’s one data point from a paper by J. N. Heard: The Assimilation of Captives on the American Frontier in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries,

The colonial history of North and South America is full of accounts of settlers, captured or adopted by indigenous societies, being given the choice of where they wished to stay and almost invariably choosing to stay with the latter. P. 19.

Benjamin Franklin agreed! P. 20.

Returning to the third point, the standard account of the history of human societies says that there is a natural and inexorable progression from band to tribe to city to our current apogee of hierarchy, state violence, and jacking up the price of life-saving drugs. Western cultures are founded on the idea that market exchange is the most important aspect of human character when it comes to organizing societies. If we dump that notion we can imagine all sorts of possible organizations of society that would be more interesting. Here’s a taste.

The founding text of twentieth-century ethnography, Bronisław Malinowski’s 1922 Argonauts of the Western Pacific, describes how in the ‘kula chain’ of the Massim Islands off Papua New Guinea, men would undertake daring expeditions across dangerous seas in outrigger canoes, just in order to exchange precious heirloom arm-shells and necklaces for each other (each of the most important ones has its own name, and history of former owners) – only to hold it briefly, then pass it on again to a different expedition from another island. Heirloom treasures circle the island chain eternally, crossing hundreds of miles of ocean, arm-shells and necklaces in opposite directions. To an outsider, it seems senseless. To the men of the Massim it was the ultimate adventure, and nothing could be more important than to spread one’s name, in this fashion, to places one had never seen. P. 22-2.

That’s just cool.

Discussion

1. The discussion of inequality in Chapter 1 reminds me of the work of the philosopher Elizabeth Anderson which I discussed in this series. Anderson identifies several forms of equality that go beyond mere material measures. She help us see why material equality is an inadequate measure of equality. In short, we are much more than merely homo economicus. We want more from life than piles of stuff.

In my series on the work of Pierre Bourdieu I discuss his ideas about how dominant class reproduces itself. If the dominant class has the ability to convert material wealth into political and social power, we can see that the dominant class can use its material capital to push people into working really hard to preserve the wealth of the rich, to increase it, and to remove restraints on the use of wealth and power.

2. John Maynard Keynes agrees with Graeber and Wengrow that material wealth is the primary organizing principle in current social arrangements. This is from his 1926 essay On The End Of Laissez-Faire, which I discuss here in another context. Here’s a link to the essay. Section V is particularly relevant.

In Europe, or at least in some parts of Europe – but not, I think, in the United States of America – there is a latent reaction, somewhat widespread, against basing society to the extent that we do upon fostering, encouraging, and protecting the money-motives of individuals. A preference for arranging our affairs in such a way as to appeal to the money-motive as little as possible, rather than as much as possible, ….

Maybe we should think about whether we’d like to reduce the role of the money-motive in our lives. We can’t do it alone. But if all of us were to decide to do that, our lives might be more interesting.