Expressions Of Individuality In Democracy

I gave a tentative description of what it means to be an individual here, including speculation about mechanisms. In this post, I will add some detail on mechanisms, and try to sharpen up the notion of individuality.

More on mechanisms

In his book The Evolution of Agency, Michael Tomasello describes self-monitoring as a feedback loop. We set a goal, then form a plan to reach the goal, and self-monitor to see how well the plan is working. Setting goals and making plans can also be seen as feedback loops. We consider possibilities,, consider their ramifications, and choose. Self-monitoring systems can be used to rank and to modify goals. The process of setting goals also seems close to the neuronal firing I discussed in the linked post.

That description suggests that our brains operate with nested and linked feedback loops. Years ago I read Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid by Douglas Hofstadter. There are lengthy discussions of Bach fugues, Escher’s astonishing prints, and Gödel’s theorems. It left me with a strong sense that our neuronal structures use recursion to formulate plans.

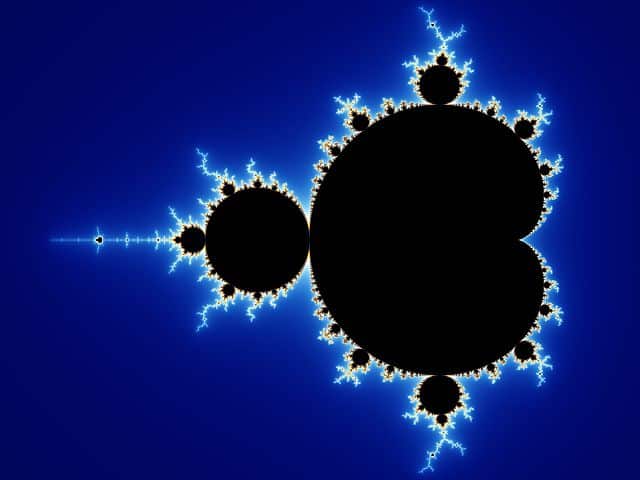

In math, a recursive function is a series of calculations using a single equation. The value of the equation is first calculated using a seed. Next the equation is calculated again, using the result of the first calculation. This process continues until the result of two consecutive iterations is the same, or until the value gets too large. The Mandelbrot Set is reached by such a function. The calculations start with a simple equation, and each point in the plane is defined by whether the calculations converge or grow to infinity.

We can compare Tomasello’s feedback loops to Hofstadter’s recursion. The crucial point for our purposes is that small changes in the initial conditions of both might (or might not) produce radically different outcomes.

There are, I think, limits to the amount of variation in human brains. We have physical limitations at every level of our existence, and presumably that’s true of our brain activity. From birth we train our brains to do the things we need to do to survive. That strengthens certain neural activity and weakens the possibility of other, different thoughts and actions. This comment by community member PeaceRme gives an excellent description of the impact of domestic violence on people’s thought processes.

Tomasello says social norms play a large role in determining our behaviors. We are likely to try to conform our actions and our thinking to the norms of our group. When a person’s brain produces actions that are too far outside the range our society thinks is normal, we consider the person sick and take action to protect ourselves from them, maybe even to try to heal them.

Of course, this is all rank speculation. I enjoy the speculation; it’s fun to think about things you don’t fully understand. It’s delightful when things you’ve read at different times and for different reasons seem to fit together.

A closer look at individuality

Several commenters point out that people show individuality in their personal lives, so what’s my point. This comment by community member Eschscholzia is an excellent example. Another way to see this is to look at random bios on Bluesky. People describe themselves in terms of their interests, favorite sports teams, or basic political stances. These are indeed facets of individuality.

When I started this series, I was thinking that the question was something like: what part of your persona consists of choices you made after due consideration, and what part are habits you learned without conscious choice. For example, I have thought a lot about why I support democracy. On the other hand, I never thought about why I don’t like celery. I just don’t like it so there. I have given at least some thought to almost all of my political views. I give very little thought to choosing sports teams.

I think some things are more important than others. Democracy is more important than celery. The things that establish the conditions under which we all live are more important than the activities that give us pleasure. So, democracy is more important than my singing career.

I’ve been trying to read The Human Condition (1956) by Hannah Arendt. Shortly after I started it, I read a discussion of the book in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy to get an overview of the book.

Arendt thinks we have lost something important in the current era, something she sees in the past. This is from the linked article.

For Arendt modernity is characterized by the loss of the world, by which she means the restriction or elimination of the public sphere of action and speech in favor of the private world of introspection and the private pursuit of economic interests. …

Snip

Arendt articulates her conception of modernity around a number of key features: these are world alienation .… World alienation refers to the loss of an intersubjectively constituted world of experience and action by means of which we establish our self-identity and an adequate sense of reality.

Arendt describes the active life as consisting of three parts — labor, work, and action. Labor is the things we do to keep ourselves functioning, sleeping, bathing, eating. Work is the things we do to produce goods and services necessary or useful in our daily lives. Action is, in essence, our participation in public life. There we use our rational skills in politics, poetry, the other arts, In the process make ourselves, our true selves, known to others, and, I think, indirectly to ourselves.

Arendt thinks that action is the most important aspect of our existence. As to politics, she thinks the ancient Greeks had the power to make joint decisions about crucial matters, from war to the rules that make society better.

She thinks the rise of totalitarian states, the rise of huge bureaucracies, and a change in our relation to work have changed us. We focus on material goods and our groups of friends and family, and we forego the power to plan for our future as a species.

I think this is right. Our highest and best calling is to contribute our thinking and our actions to making a society that will be better for us, all of us, and our children, all of our children. Of course that isn’t our sole goal, we want and need to attend to all our abilities, including the ability to experience pleasure.

Democracy gives us the opportunity to do both. We should consider our individuality to consist of our power of reason, our experience, and all our personal qualities, those we display in our family life, and among our friends. All democracy asks of us is that we use that individuality to form a shared intersubjective conception of reality, to identify our problems, and to devise solutions. We have the tools. We just need the will.