Jeff Gerth began his series on the press’ Russia investigation failures by noting that trust in the traditional media collapsed after the 2016 election (a claim based on a statistical error), with a sharp rise in concern about “fake news” and, according to Rasmussen, half of those surveyed thinking the press was the enemy of the people.

Before the 2016 election, most Americans trusted the traditional media and the trend was positive, according to the Edelman Trust Barometer. The phrase “fake news” was limited to a few reporters and a newly organized social media watchdog. The idea that the media were “enemies of the American people” was voiced only once, just before the election on an obscure podcast, and not by Trump, according to a Nexis search.

Today, the US media has the lowest credibility—26 percent—among forty-six nations, according to a 2022 study by the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. In 2021, 83 percent of Americans saw “fake news” as a “problem,” and 56 percent—mostly Republicans and independents—agreed that the media were “truly the enemy of the American people,” according to Rasmussen Reports.

Gerth believes part of the problem stems from an erosion of journalistic norms, which he listed at length in an afterward, starting with the press’ unwillingness to report facts that run counter to the prevailing narrative.

My main conclusion is that journalism’s primary missions, informing the public and holding powerful interests accountable, have been undermined by the erosion of journalistic norms and the media’s own lack of transparency about its work. This combination adds to people’s distrust about the media and exacerbates frayed political and social differences.

One traditional journalistic standard that wasn’t always followed in the Trump-Russia coverage is the need to report facts that run counter to the prevailing narrative.

And in spite of his citation of WaPo’s tracking of the vast number of lies Donald Trump told during his term early in the series, Gerth put great stock in what Donald Trump told him in two interviews, adopting Trump’s attribution of the coverage of Russia for the reality TV star’s decision to start labeling the media, “fake news.”

He made clear that in the early weeks of 2017, after initially hoping to “get along” with the press, he found himself inundated by a wave of Russia-related stories. He then realized that surviving, if not combating, the media was an integral part of his job.

“I realized early on I had two jobs,” he said. “The first was to run the country, and the second was survival. I had to survive: the stories were unbelievably fake.”

This is a critical point: Gerth appears to believe Trump that called the media “fake news” not as part of an effort to manipulate the media or to damage one of the institutions of accountability that might check his power, but instead as part of a good faith response to coverage of him.

From that premise, CJR decided the way to understand the collapse in trust of the media was to focus largely on NYT and WaPo’s performance in their coverage of Russia.

CJR editor Kyle Pope told me,

What we wanted to do with this piece was focus entirely on the media coverage, without the usual notes about Trump’s failings. Specifically, we wanted to focus largely on the New York Times and the Washington Post, as important leaders of the coverage. This was not intended as a 360-degree roundup of everything written about Trump and Russia.

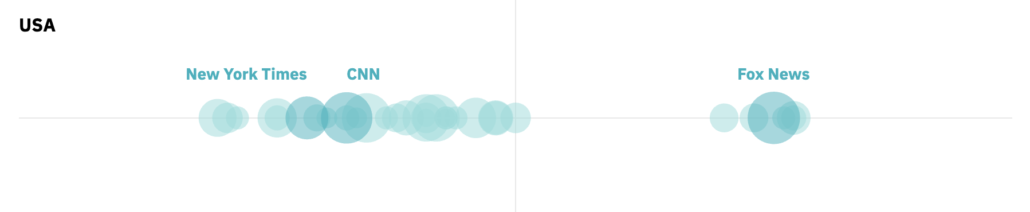

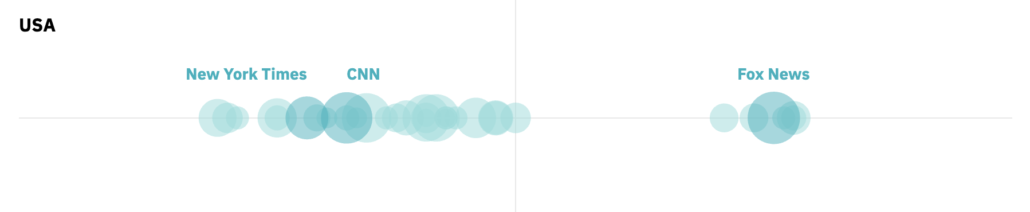

There are obviously enormous problems with the conception of this project, particularly with media polarization in the US that looks like this (a source Gerth relied on to assess the problem).

Others engaged in the “Russiagate” project correctly recognize the import of cable news in the equation (though most, like Glenn Greenwald, ignore the power of the self-contained bubble around Fox, which doesn’t even attempt to hold itself to standards of truth). In 23,000 words, for example, Gerth never considers whether Fox’s scandalous Seth Rich coverage fostered distrust of the media.

In his series, Gerth spent a great deal of time questioning claims about the impact of Russia’s social media operation in 2016 (which, like many “Russiagate” analysts, he treats as the only possible means by which Russia influenced the election). But he didn’t consider the impact of social media, generally, on this decline in trust, not even in the vast reaches of America where there is no more local news, where news consumers increasingly rely on information fed by algorithms that reward the most inflammatory information, from whatever source.

So even on its own terms, it’s a project designed to fail, because it ignores centrally important parts of the equation.

Worse still, Gerth didn’t even carry out what he claimed to set out to do.

That’s actually one of the reasons I’ve spent so much time dissecting his effort: because the ways in which he claimed to limit his scope, and his deviation from that scope, is itself very telling.

Gerth shows how little WaPo and NYT chased the dossier

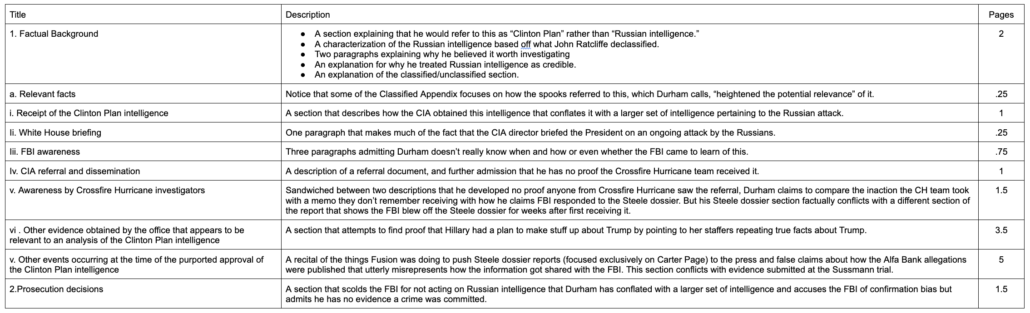

Start with his focus on the Steele dossier. The dossier is mentioned or discussed in paragraphs making up over 5,000 words out of Gerth’s 23,000-word series. That’s consistent with the “Russiagate” project, which often treats the dossier as stand-in for the entire Russian investigation (or, here, the coverage of it).

Even regarding the Steele dossier, Gerth’s own summary of their coverage makes it clear that the NYT and WaPo aren’t the villains of the dossier story. The villains in his account are Michael Isikoff, David Corn, CNN, BuzzFeed, McClatchy, and Jane Mayer.

Gerth struggled to implicate NYT and WaPo in his dossier complaint. He noted that NYT mentioned it, including FBI’s efforts to reach out to its sources, in a February 14, 2017 article he spends almost 1,000 words attacking.

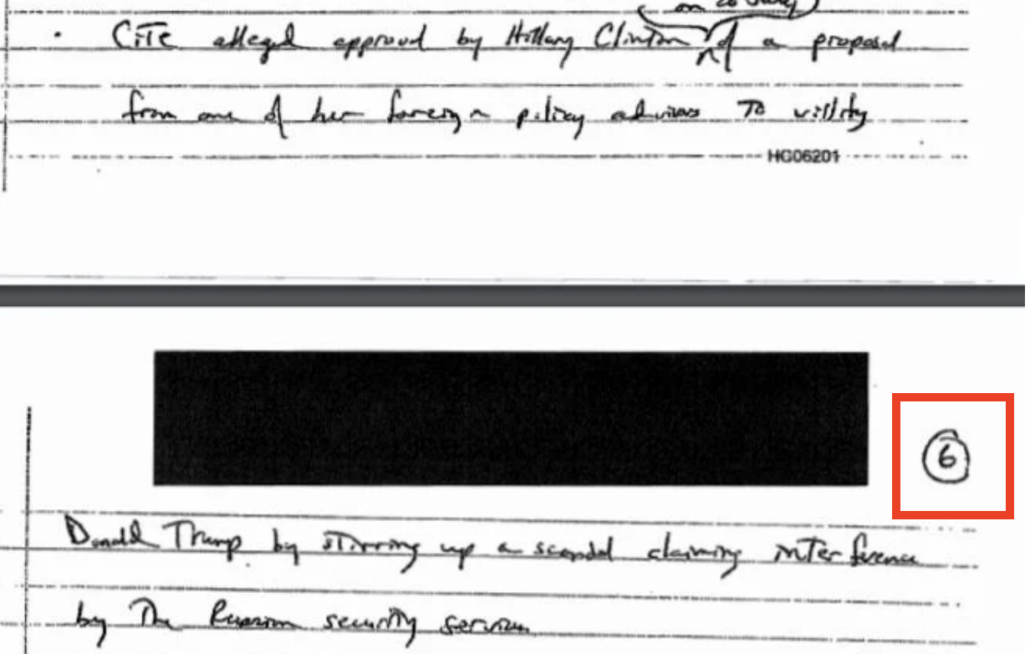

In the article’s discussion of the dossier, it described Steele as having “a credible track record” and noted the FBI had recently contacted “some” of Steele’s “sources.” Actually, the FBI had recently interviewed Steele’s “primary” source, a Russian working at a Washington think tank, who told them Steele’s reporting was “misstated or exaggerated” and the Russian’s own information was based on “rumor and speculation,” according to notes of the interview released later. The day the Times piece appeared in print, Strzok emailed colleagues and reported that Steele “may not be in a position to judge the reliability” of his network of sources, according to Justice Department documents released in 2020.

But as I note below, the dossier is in no way Gerth’s primary complaint with this article and others in a series of similar reports from NYT.

Gerth also included the dossier in a critique of NYT’s reporting on the Nunes Memo.

At the Times, the coverage of the GOP memo was skeptical while a dueling memo, a few weeks later from the ranking Democrat on the committee, was portrayed more favorably.

The Times, at the start of the piece about the Republican memo, called it “politically charged”; noted, in the next sentence, how it “outraged Democrats”; and did not quote the memo’s allegation of the dossier’s “essential” role in the surveillance. The same day, in a separate piece, the Times again called the GOP memo “politically charged” and quoted the “scathing” criticism by Democrats.

Later that month, the Democrats released their own memo. It said the surveillance warrant “made only narrow use of information from Steele’s sources.” The Times story called it a “forceful rebuttal” to Trump’s complaints about the FBI’s inquiry. In the end, the allegations of abuse by Nunes were confirmed in 2019 when the Inspector General released a report that was a “scathing critique” of the FBI, as the Times told readers at the time.

In a statement to CJR, the Times said: “We stand behind the publication of this story,” referring to its reporting on the Nunes memo.

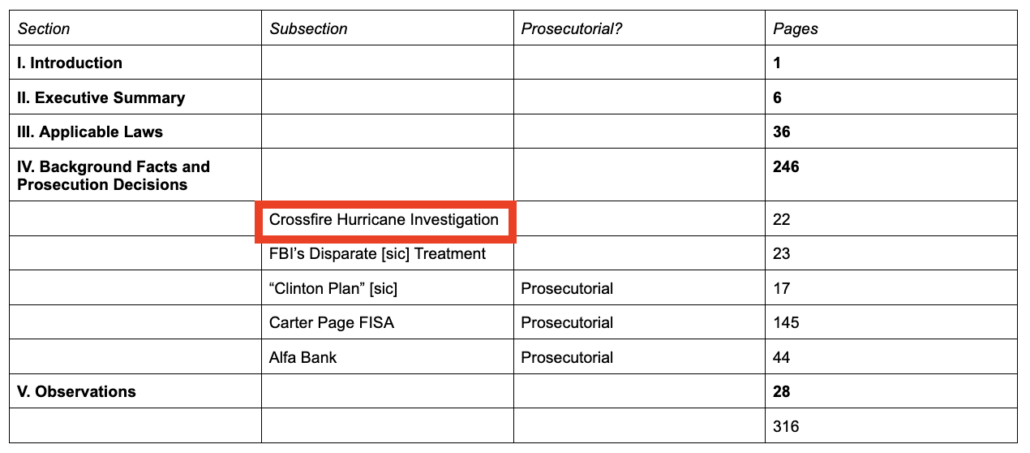

In doing so, he overstates the extent to which the DOJ IG Report on Carter Page, “confirmed” Nunes’ claims. As I noted in a claim-by-claim assessment after the release of the report, both memos got things wrong and both got things right, and Democrats were right that the dossier was not part of the predication of the Russian investigation. Mostly, though, they were just talking past each other, a problem exacerbated by the secrecy behind which both sides could hide their arguments.

Gerth found a little more to work with in the WaPo.

He made much of the fact that one journalist on a long (and accurate) piece about Trump’s ties to Russia was friends with Glenn Simpson, one of the founders of Fusion GPS, via which the Democrats paid for the Steele dossier.

The lead author of the story, Tom Hamburger, was a former Wall Street Journal reporter who had worked with Simpson; the two were friends, according to Simpson’s book. By 2022, emails between the two from the summer of 2016 surfaced in court records, showing their frequent interactions on Trump-related matters. Hamburger, who recently retired from the Post, declined to comment. The Post also declined to comment on Hamburger’s ties to Fusion.

Here was a tie, Gerth insinuated, that proved journalism collapsed in the face of Hillary’s attempts to push oppo research.

But 1,500 words later in Gerth’s series, he showed that Hamburger pushed back on Fusion tips like the Carter Page one when he couldn’t substantiate them.

[S]ome reporters, aware of the dossier’s Page allegations, had pursued them, but no one had published the details. Hamburger, of the Washington Post, told Simpson the Page allegations were found to be “bullshit” and “impossible” by the paper’s Moscow correspondent, according to court records.

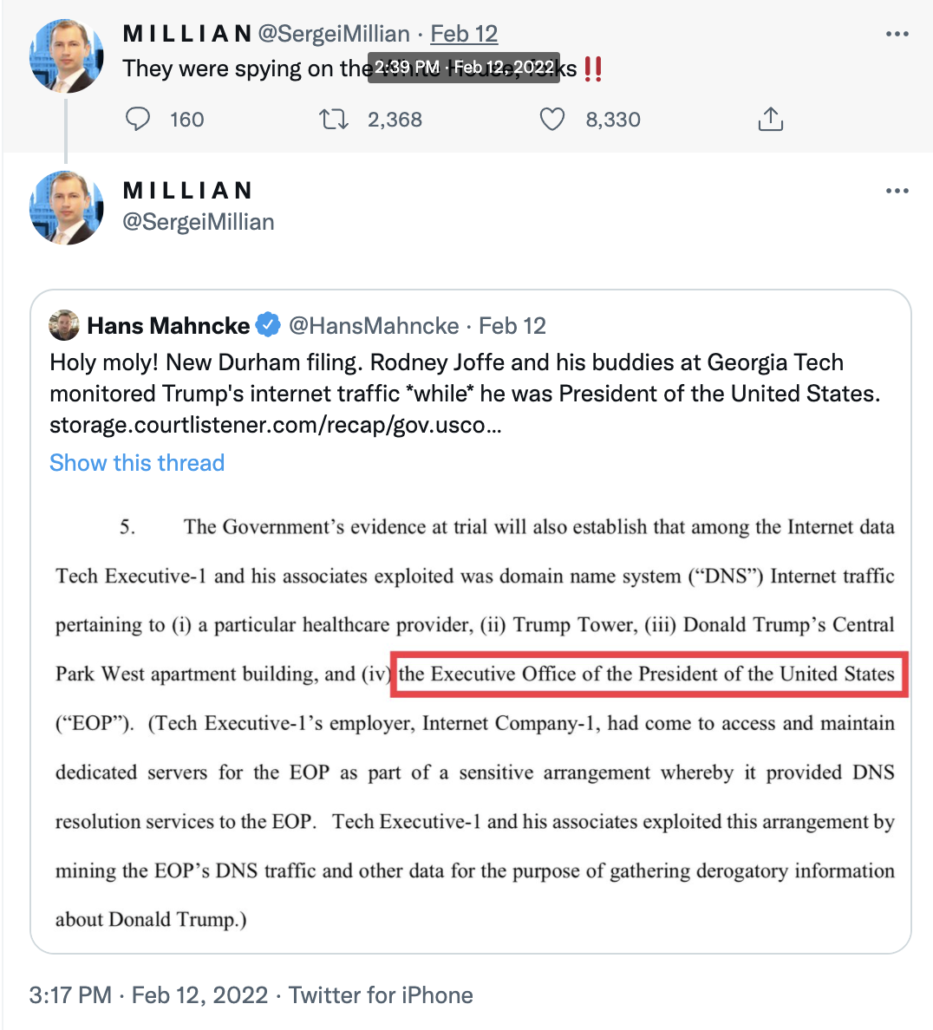

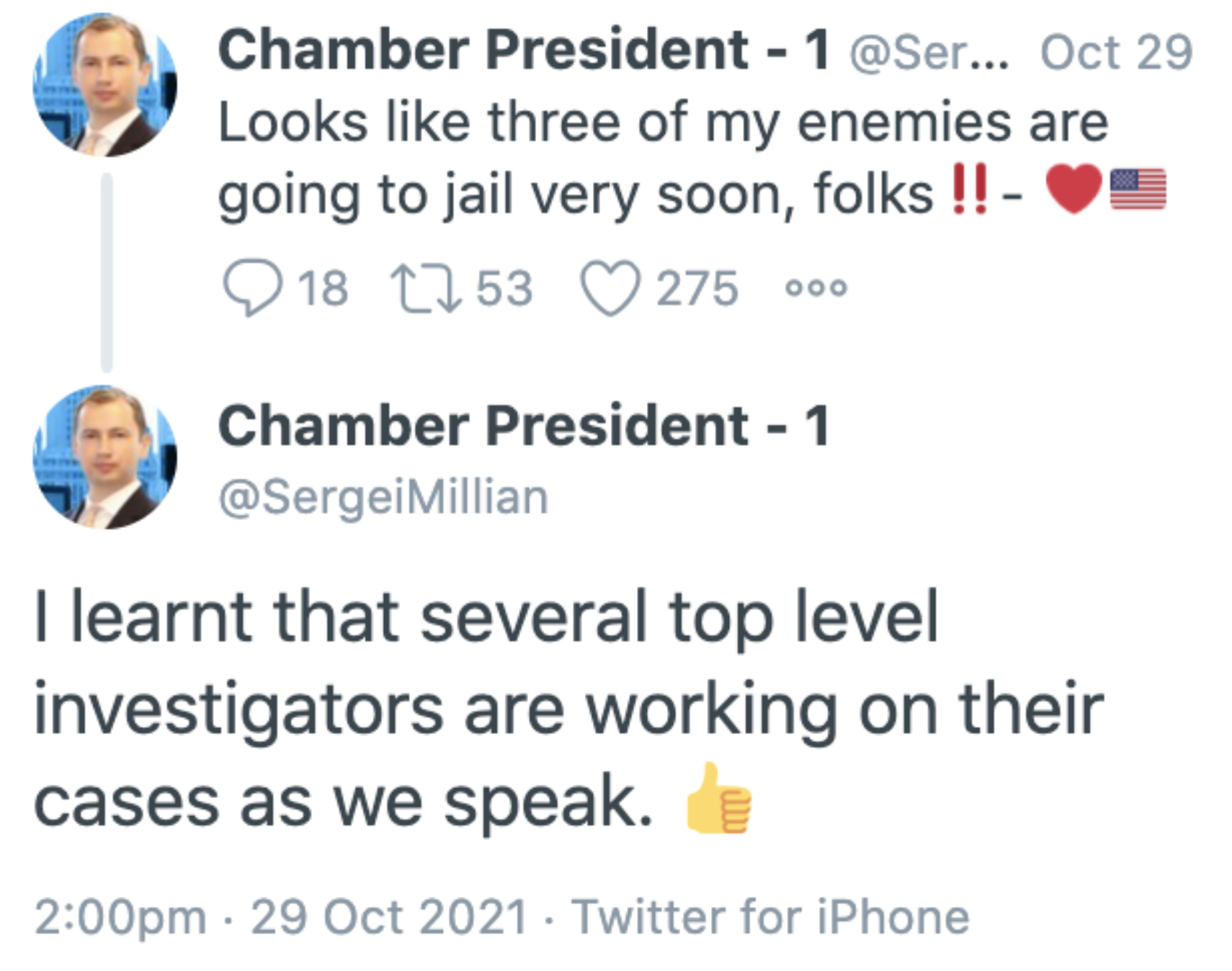

That’s important background to Gerth’s coverage of WaPo’s 2017 story on Sergei Millian.

The Post landed a long story about Sergei Millian, a Belarusian-American businessman, on March 29. The top of the piece identified Millian as the source behind the dossier’s most serious allegation, a “well-developed conspiracy” between the Trump campaign and the Kremlin, the same ground covered by the Wall Street Journal and ABC in January. The claim that Millian was a key informant whose information was “central to the dossier” was stated without any attribution or sourcing. In 2021 the Post retracted the parts of the story describing Millian as a dossier source after John Durham, a special counsel looking into the origins of the Trump-Russia investigations, indicted Steele’s main source for lying to the FBI. Durham alleged the fact of Millian being a source had been “fabricated.” The Post editor’s note explained that Durham’s indictment “contradicted” information in the March story, and additional reporting in 2021 further “undermined” the account. The Post also deleted parts of a few other stories that repeated the allegation that Millian was a dossier source.

WaPo retracted much of the story after the Danchenko indictment, with this editor’s note:

The original version of this article published on March 29, 2017, said that Sergei Millian was a source for parts of a dossier of unverified allegations against Donald Trump. That account has been contradicted by allegations contained in a federal indictment filed in November 2021 and undermined by further reporting by The Washington Post. As a result, portions of the story and an accompanying video have been removed and the headline has been changed.

The original account was based on two people who spoke on the condition of anonymity to provide sensitive information. One of those people now says the new information “puts in grave doubt that Millian” was a source for parts of the dossier. The other declined to comment.

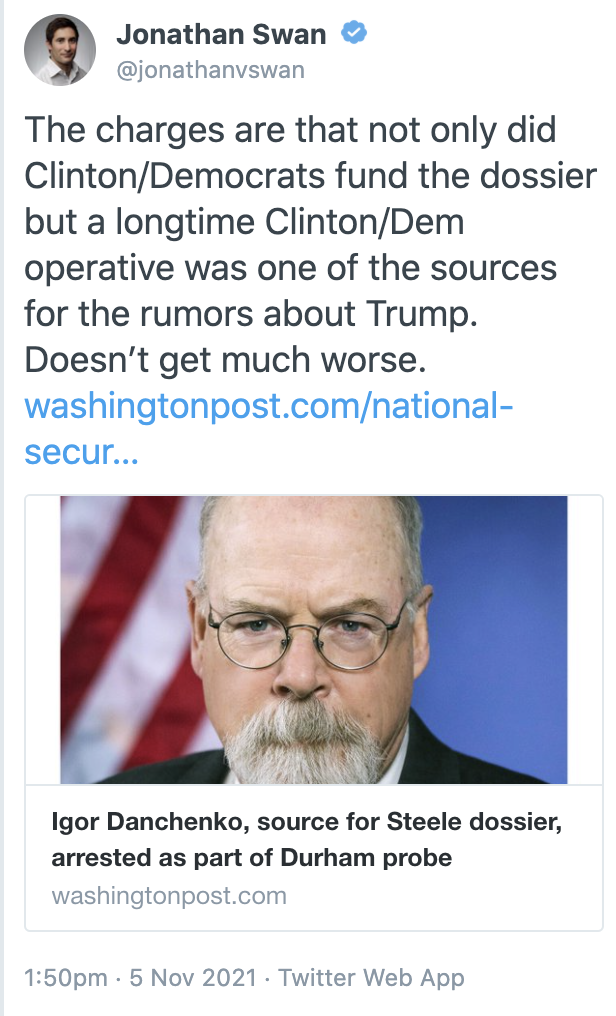

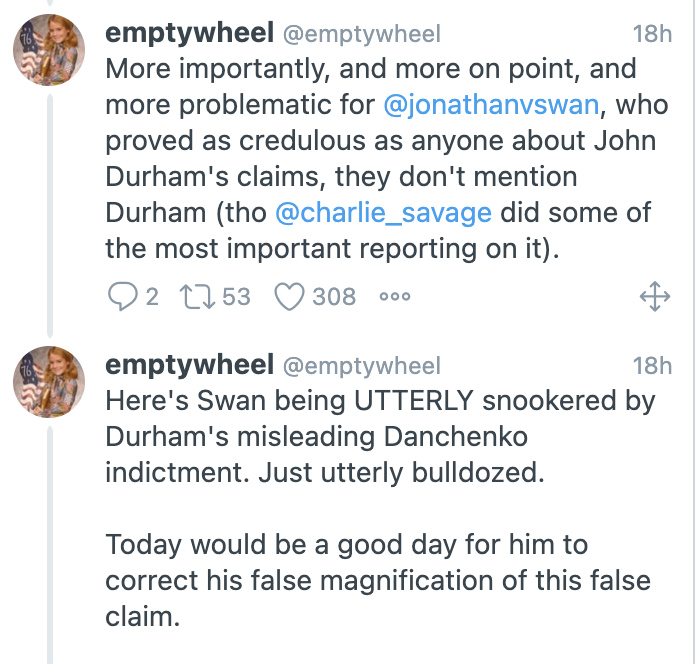

WaPo’s retraction (like the CNN “reckoning” which Gerth cites approvingly) were themselves problematic, because (as I noted about the CNN piece) they took John Durham’s false statements indictment against Steele’s primary subsource, Igor Danchenko, insinuating — but falling far short of charging — a conspiracy as a source of fact. Worse still, the indictment was obviously problematic. In it, Durham relied on Millian’s claims, made on social media but not to a grand jury, for a key part of his case. After Millian refused to testify at trial, Durham admitted he had little but hearsay to prove his case.

And as Danchenko attorney Stuart Sears noted at trial, several of Millian’s communications, in which Millian boasted about his ties to Trump, were consistent with Danchenko’s claims about the call he attributed to Millian.

It’s entirely possible it wasn’t Sergei Millian, but even if it was, the caller only said there was coordination between the campaign and Russia and that there was nothing bad about it. Agent Helson told you that. That’s not anti-Trump, and we do know from the government’s own evidence that Millian was at least telling people he was going to meet with Trump campaign people the week before the phone call, the anonymous phone call.

Gerth cheered retractions based off an indictment alone over three months after a jury acquitted Danchenko of lying about this call, which he told the FBI he believed, but was not certain, came from Millian.

And Gerth, who complains about transparency, buried that fact: while Gerth emphasized the WaPo and CNN retractions in Part Two of his series, he didn’t get around to informing readers that Igor Danchenko had been acquitted until Part Four, over 9,000 words and two clicks later.

Gerth elsewhere noted that Mueller’s indictments against Yevgeniy Prigozhin and the GRU hackers haven’t been tried, yet when it served his narrative, he applauded these retractions based on an indictment alone.

Meanwhile, Gerth credited WaPo with breaking the news that the Democrats had funded the dossier, which is ample proof that the WaPo wasn’t shielding the project.

Amazingly, Gerth complained that the NYT didn’t retract anything in the wake of the Danchenko indictment, even though he found so little to complain about in the NYT coverage of the dossier and even though, as he describes, WaPo’s Erik Wemple (who might consider whether his own campaign for dossier accountability went too far, in light of the Danchenko acquittal) called out NYT’s Adam Goldman as one of those who approached the dossier responsibly. Gerth even noted that the NYT acknowledged the flimsiness of the dossier’s allegations in real time.

The Times has offered no such retraction, though the paper and other news organizations were quick to highlight the lack of firsthand evidence for many of the dossier’s substantive allegations;

It’s genuinely not clear what Gerth thinks the NYT should retract, a question I posed to Pope that he declined to answer.

And Gerth makes this complaint even though his series was published four days after NYT’s bombshell report of how corrupt the Durham investigation was. Somehow CJR didn’t find time to remove or amend Gerth’s complaints about NYT’s critical reporting on the Durham investigation, including his complaint that Goldman suggested a junket Barr and Durham took to Italy might be chasing a “conspiracy theory,” when the recent NYT report has revealed it was far worse.

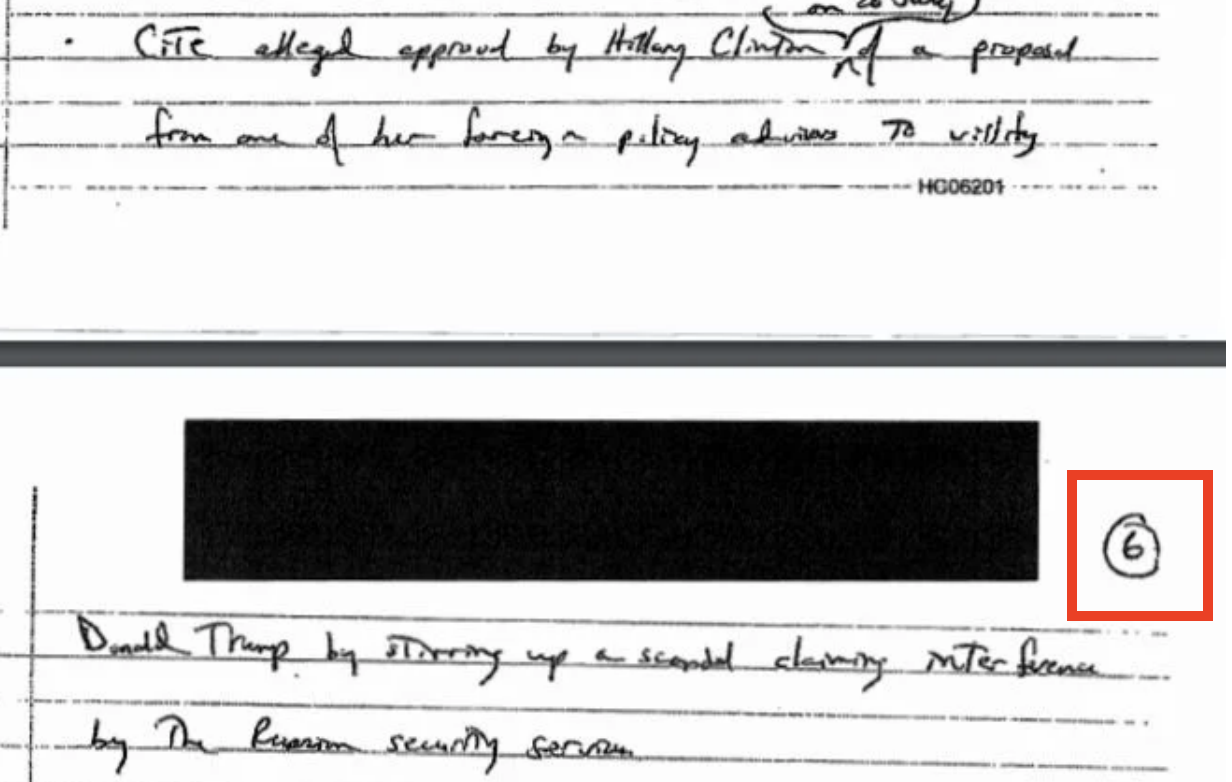

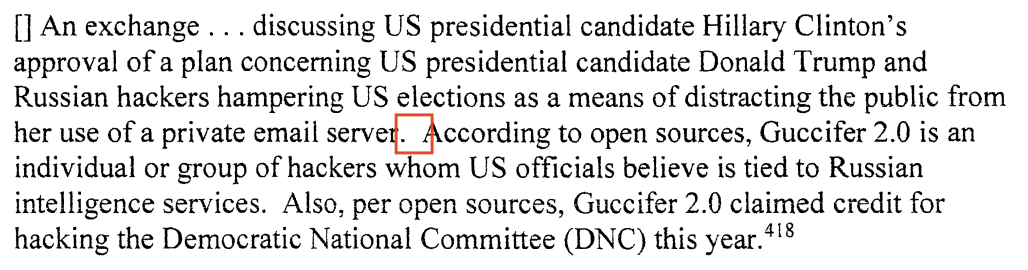

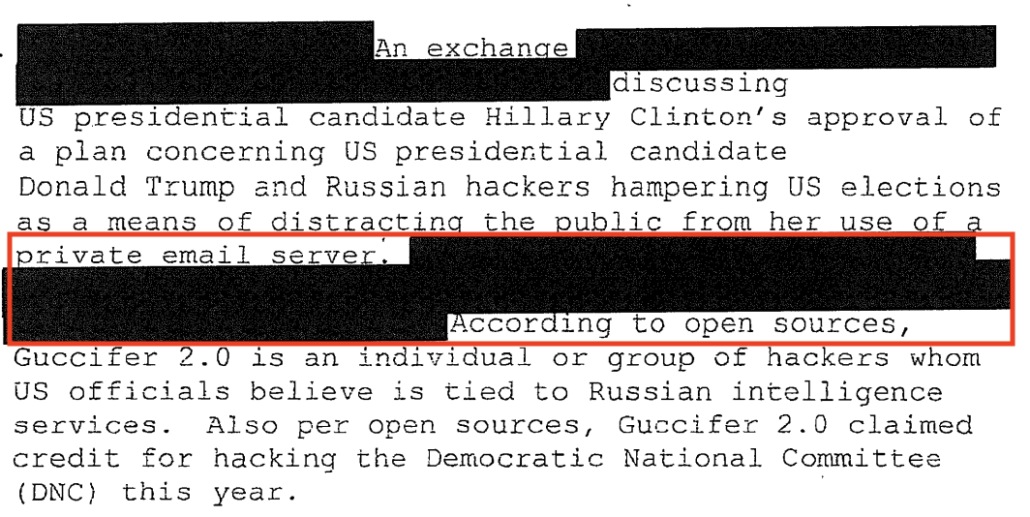

There are other grave problems with Gerth’s treatment of the dossier, all consistent with the ”Russiagate” project more generally. The DOJ IG Report Gerth relies on so heavily laid out abundant reason to suspect that Russia larded the dossier with disinformation, probably with the participation of Manafort associate Oleg Deripaska.

That’s important given the fragments of truth that appear in the dossier. As Durham briefly acknowledged at trial and as I noted in an interview hosted by CJR, the reason Danchenko’s ties to Clinton ally Chuck Dolan were so significant, and led Durham to charge Danchenko for making a “literally true” statement about Dolan to the FBI, was that Dolan established ties between Olga Galkina — the source of the most problematic claims in the dossier, alleging Michael Cohen spoke directly with the Kremlin about election interference — and Dmitri Peskov. The link raises the possibility that someone who knew about Michael Cohen’s January 2016 call to the Kremlin, to Peskov’s office, a call both Cohen and Trump lied to conceal, was behind the dossier allegation that falsely claimed Cohen had other contacts with the Kremlin. Peskov knew that Cohen and Trump were lying to hide that earlier contact, which made the later false allegation more powerful.

Other records show that Russia likely used Steele for a functional role in their operation. In spring 2016, Deripaska is believed to have been the client who hired Steele for intelligence collection targeting Paul Manafort. Then Deripaska used Steele as part of a brutal double game with Manafort. Essentially, Deripaska used the former British spy’s association with the FBI to increase Manafort’s legal vulnerability while he had Kilimnik exploit Manafort’s financial vulnerability, all of which made it easier to obtain inside information on the Trump campaign at the August 2 meeting.

And, in a story about the dossier that Gerth doesn’t mention, Manafort came back from what we now know to be a meeting with a Deripaska associate and told Reince Priebus to focus on the dossier’s inaccuracies as pushback on the Russian investigation. That is, the focus on the dossier as a substitute for Trump’s real Russian ties seems to have become part of Russia’s plan, if it wasn’t from the start. If the dossier was deliberate disinformation — and the Republican members of Congress who investigated that document insist it was — then it must be considered part of Russia’s attack on US democracy – in which Gerth and other “Russiagate” participants are enthusiastic participants.

Polarization and trust in the media lie at the center of Gerth’s project. Yet he failed to consider how the dossier, not the coverage of it, might be a key driving factor in polarization. That makes his project part of the problem.

Gerth’s selective coverage of NYT and WaPo’s Pulitzer-winning journalism

Even while Gerth failed to significantly implicate NYT and WaPo in what he portrays as the gravest journalistic crime in Russian coverage, hyping the Steele dossier, he also ignored key parts of their coverage.

For example, he didn’t acknowledge that WaPo reported on Carter Page’s inflammatory comments in Moscow weeks before Steele did. Much of the focus on Page subsequent to WaPo’s report was based on this public source, not the dossier. It’s one of many events that the press covered for its real news value that Gerth, in his own narrative, suggests could only have happened with Hillary’s intervention.

Gerth also ignored large swaths of NYT and WaPo’s award-winning journalism on Russia, although he covered Trump’s attack on that reporting in the third installment of his series.

NYT won a Pulitzer in 2017 for ten Russia-related articles and NYT and WaPo shared a prize for a combined 20 stories on the Russian investigation in 2018. Trump has sued the Pulitzer Board for defamation relating to the 2018 award. In his coverage, Gerth suggests that Trump’s lawsuit against the Pulitzer Board for those awards has merit.

Best as I’ve been able to reconstruct, this page lists the newspaper coverage mentioned in Gerth’s series (in numerous ways, CJR’s decision not to link the media Gerth claimed to discuss made it very difficult to assess his claims, and I made one error in my questions to CJR as a result). The page also lists, at the end, some key stories that Gerth did not address. Those with asterisks — both in the stuff he covered and the stuff he did not — were part of the Pulitzer packages for which NYT and WaPo won prizes.

Gerth included just one of the stories for which NYT won a Pulitzer in 2017, the Manafort secret ledger story (the same story, as Fusion GPS revealed after Barry Meier attacked them in a book, for which Fusion provided research).

But he ignored the rest.

That had the effect of hiding the general background on Russia’s international assault on its opponents that NYT, as an institution, would have brought into its coverage of Trump’s suspected ties to the Kremlin in 2017: stories about Russia hunting down its enemies in other countries, Russia’s use of disinformation, the elite hackers Russia was recruiting, and Russia’s cultivation of the far right.

Gerth also ignored two stories that were specifically on point to his project: A September 2016 story revealing how often Julian Assange’s Wikileaks releases served Russia’s political interests (I raised some concerns about the piece here), and a December 2016 epic that described the Russian hack-and-leak from the DNC perspective (I pointed out the DNC’s changing story about being warned by the FBI here). The DNC story should be particularly important to Gerth’s project because it explicitly made the comparison with the Watergate burglary in 1972 that Gerth complains about in his series. It also provided a great deal of information, much publicly available, backing the hack-and-leak attribution to Russia – an attribution that Gerth claims remains “far from definitive.”

I asked Pope why the Assange and the DNC hack stories weren’t included in the series. He pointed to coverage of other NYT stories as proof CJR wasn’t ignoring the (2017, not 2018) Pulitzer stories.

Do you think it fair to ignore all the stories for which WaPo and NYT did get Pulitzers, including the 2017 ones on WikiLeaks and the DNC hack?

We didn’t ignore them. From the piece: “For the Times, Trump’s mess was a pot of gold: two of the Times stories about the meeting and the emails were part of its winning Pulitzer Prize package.

And … “But before that omission, the Times exposed another piece of the FBI’s Russia puzzle. The paper landed a major story at the end of the year, in time to be included in its Pulitzer package that ultimately shared the prize for national reporting.”

But there were a bunch of Pulitzer winners Gerth left out whose omission is still more problematic, particularly given his suggestion that the entirety of the press’ early 2017 focus on Russia in Trump’s administration stemmed from the publication of the dossier.

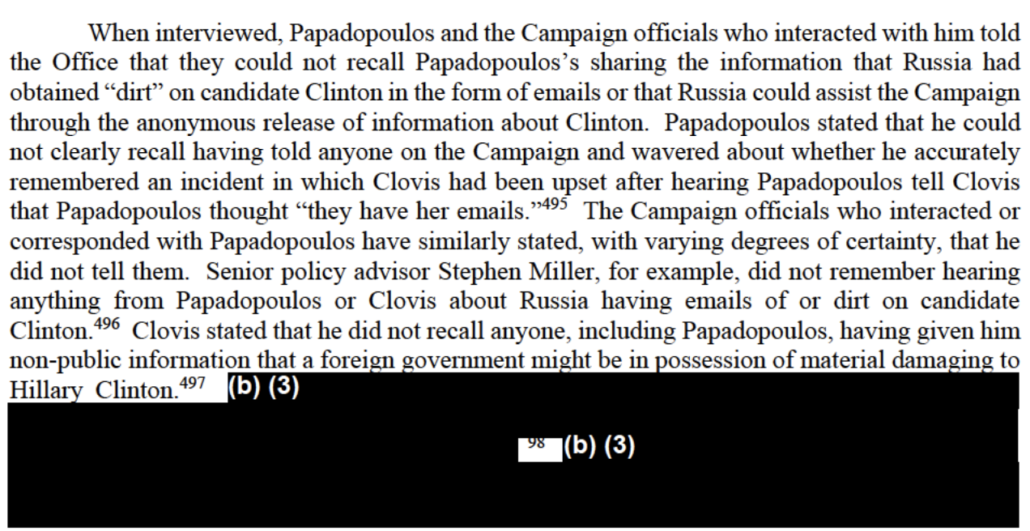

For example, Gerth barely mentions the coverage of Mike Flynn’s lies and resignation and its central role, starting even before the publication of the dossier, in press coverage in early 2017. He slips discussion of a key David Ignatius column, the first to report on Mike Flynn’s calls with Russian ambassador to the US, Sergei Kislyak, in between his references to the dossier.

The WSJ and the Times stories were not well received by Fusion. At first, they feared for Steele’s safety. Then they felt the Times’ behavior was “improper,” because it had “unilaterally” published material “it had learned off the record,” the founders wrote in their book.

Hours after the Times story ran, the Post upped the temperature on Russia even more. Columnist David Ignatius disclosed that incoming national security adviser Michael Flynn had phoned Russia’s US ambassador “several times” at the end of the year, according to “a senior US government official.” Ignatius noted the talks had come on the day the Obama administration had expelled Russian diplomats in retaliation for the country’s hacking activities, so he questioned whether Flynn had “violated” the spirit of an “unenforced” law barring US citizens from trying to resolve “disputes.”

Ignatius went on to write that it might be a “good thing” if Trump’s team was trying to de-escalate the situation. But Ignatius didn’t know the substance of the conversations. Hours before his story went online, Ignatius appeared on MSNBC and, while not disclosing his upcoming Flynn exclusive, said “it was hard to argue” against the need to “improve relations with Russia.”

The existence of Flynn’s talks with the ambassador was known by Adam Entous, a reporter then at the Post, but he held off writing anything because the mere fact of a contact wasn’t enough to justify a story. “It could have been something innocent,” Entous, now with the Times, said in an interview, “something he would be praised for.”

On the heels of the Ignatius column, the FBI’s “investigative tempo increased,” according to FBI records, and the Senate intelligence panel announced an inquiry into Russia’s election activities. (The House Intelligence Committee announced a similar effort later that month.)

Two days after the Senate announcement, Bob Woodward, appearing on Fox News, called the dossier a “garbage document” that “never should have” been part of an intelligence briefing.

But he doesn’t reveal why the FBI’s investigative tempo increased in the wake of Ignatius’ column.

Stories that the WaPo published that he ignored did. A Pulitzer-winning WaPo report published the same day revealed that Flynn was denying he had discussed sanctions with the Russian Ambassador, the first of many compromising lies Trump’s associates told in the early days of his Administration. Flynn’s lies (as Mueller confirmed in his congressional testimony) created the risk that he could be blackmailed, which led the FBI and DOJ to respond more aggressively than they otherwise might have. Another Pulitzer-winning WaPo story explained all that on the day Flynn resigned.

Later in the spring, a Pulitzer-winning NYT report revealed that Trump knew Flynn was under investigation for his secret relationship with Türkiye even before the president appointed him to be National Security Adviser. Gerth’s silence about all these stories is particularly damning, given that he later gets a key detail about Flynn’s prosecution wrong, which I’ll return to.

Other award-winning stories revealed still more Russian ties that Trump and his associates were trying to hide. A March story from WaPo — yet another Pulitzer winner — revealed that Jeff Sessions had failed to disclose some interactions with Sergey Kislyak, the same ambassador with whom Flynn was undermining Obama foreign policy during the transition. An April Pulitzer-winning story from the NYT revealed that Jared Kushner had omitted transition period meetings with Russians — not just Kislyak, but also the head of a sanctioned bank — in his security clearance paperwork.

While Gerth may have mentioned a May article for which NYT won a Pulitzer, if he did, he did so only as part of his complaint that the NYT repeatedly referred to the line from Trump’s interview with Lester Holt in which he referred to “the Russian thing” in his explanation for firing Comey.

A tweet from the show on May 11 set the narrative for the Holt interview: “Trump on firing Comey: ‘I said, you know, this Russia thing with Trump and Russia is a made-up story.’” Those few words, by suggesting Comey’s firing was aimed at getting the FBI inquiry off his back, provided fresh ammunition to anti-Trumpers.

The full interview, which was available online, presented a more nuanced story, and appeared to reflect what his advisers told him: firing Comey could prolong, not end, the investigation. Trump told Holt, soon after the controversial words, that the firing “might even lengthen out the investigation” and he expected the FBI “to continue the investigation,” to do it “properly,” and “to get to the bottom.”

The media focused on the “Russia thing” quote; the New York Times did five stories over the next week citing the “Russia thing” remarks but leaving out the fuller context.

But Gerth’s account elided the entire reason Trump’s NBC quote was used in that particular NYT article: because Trump told Kislyak and Sergey Lavrov roughly the same thing, privately, on the same day.

President Trump told Russian officials in the Oval Office this month that firing the F.B.I. director, James B. Comey, had relieved “great pressure” on him, according to a document summarizing the meeting.

“I just fired the head of the F.B.I. He was crazy, a real nut job,” Mr. Trump said, according to the document, which was read to The New York Times by an American official. “I faced great pressure because of Russia. That’s taken off.”

Mr. Trump added, “I’m not under investigation.”

Gerth doesn’t address the real concerns presented by Trump privately bragging about firing the FBI director – in charge of counterintelligence – to his Russian visitors.

Indeed, given Gerth’s focus on Trump’s use of “fake news,” he might have at least mentioned the last lines of the NYT story:

At one point, Mr. Trump jokingly asked whether there were reporters in the room.

“No,” Mr. Lavrov said. “No fake media.”

Whether you think that Trump’s adoption of the term “fake news” was merited or not, the answer to Trump’s question, “Russia, if you’re listening,” was yes, they were.

Gerth also appears to have paid no attention to a Pulitzer-winner from WaPo written in the same time frame, revealing that Trump shared highly classified Israeli intelligence with his Russian visitors in the same meeting, another cause for concern that Gerth simply makes disappear.

Those aren’t the only damning stories Gerth ignored. As Pope emphasized to me, Gerth credited NYT for two of three Pulitzer-winning stories on the June 9 meeting that Don Jr took with a Russian lawyer in hopes of acquiring dirt on Hillary– the July 10 one revealing that Don Jr took a meeting with Russians offering dirt, and the July 11 one revealing Don Jr’s enthusiastic response. But I don’t believe he credited the WaPo for their July 31 Pulitzer-winning story revealing that Trump drafted Don Jr’s misleading statement, claiming a meeting about dirt on Hillary and sanctions relief was about adoption.

The omission is really telling given Gerth’s take on a July 19 story from the NYT (which did not win a prize). In an interview with three NYT reporters, Trump successfully got the NYT to participate in his efforts to obstruct the investigation by airing his threats to fire Jeff Sessions (he had asked Corey Lewandowski to fire Jeff Sessions on the same day). In the interview, Trump also confirmed that he and Putin spoke about the topic of his misleading statement before drafting it, meaning adoptions. But Gerth deemed that interview important primarily because Mike Schmidt asked Trump about the dossier.

A week after the Trump Tower story, the president conducted a serendipitous interview with three Times reporters, including Schmidt, who asked if Comey’s sharing of the dossier with Trump before his inauguration was “leverage.” Trump replied, “Yeah, I think so, in retrospect.”

After the Oval Office sit-down, an aide, worried about the possibility of repercussions from an impromptu interview, sought Trump’s reaction.

“I loved that,” the aide, who requested anonymity, recalled him saying. “It was better than therapy. I’ve never done therapy, but this was better.”

This is a fairly astounding view on the relative newsworthiness of the interview — I’ve pointed out the importance, to Trump’s obstructive purpose, of NYT’s decision to bury the Putin tie rather than dedicate an entire story to it. It’s also a prime example of how the unrelenting focus on the dossier by “Russiagate” adherents diverts attention from far more damning events, both creating in that unrelenting focus the narrative they claim to combat, and in the process burying the real events that “Russiagate” adherents claim could only come as part of a manufactured narrative.

I asked CJR, “Why do you believe a comment on the dossier was more important than a scoop substantiating Trump’s problematic ties to Putin?” but it was another of the questions the magazine’s editor declined to answer.

There are more Pulitzer winners that Gerth left out, including a WaPo story describing both Trump’s refusal to take steps to protect American democracy from Russian interference…

Nearly a year into his presidency, Trump continues to reject the evidence that Russia waged an assault on a pillar of American democracy and supported his run for the White House.

The result is without obvious parallel in U.S. history, a situation in which the personal insecurities of the president — and his refusal to accept what even many in his administration regard as objective reality — have impaired the government’s response to a national security threat. The repercussions radiate across the government.

Rather than search for ways to deter Kremlin attacks or safeguard U.S. elections, Trump has waged his own campaign to discredit the case that Russia poses any threat and he has resisted or attempted to roll back efforts to hold Moscow to account.

… As well as Russia’s assessment of the “staggering return” achieved by their interference operation.

U.S. officials said that a stream of intelligence from sources inside the Russian government indicates that Putin and his lieutenants regard the 2016 “active measures” campaign — as the Russians describe such covert propaganda operations — as a resounding, if incomplete, success.

Moscow has not achieved some its most narrow and immediate goals. The annexation of Crimea from Ukraine has not been recognized. Sanctions imposed for Russian intervention in Ukraine remain in place. Additional penalties have been mandated by Congress. And a wave of diplomatic retaliation has cost Russia access to additional diplomatic facilities, including its San Francisco consulate.

But overall, U.S. officials said, the Kremlin believes it got a staggering return on an operation that by some estimates cost less than $500,000 to execute and was organized around two main objectives — destabilizing U.S. democracy and preventing Hillary Clinton, who is despised by Putin, from reaching the White House.

The bottom line for Putin, said one U.S. official briefed on the stream of post-election intelligence, is that the operation was “more than worth the effort.”

But the stories from the first half of 2017 that Gerth left out are key. They not only reveal the real reason that the FBI investigation picked up in early 2017, they also show that a great deal of important journalism provided abundant reason to be concerned about all the secrets about Russia that Trump and his aides were keeping, independent of the dossier.

The contacts with Russian spies that were later confirmed

That focus – the ties with Russia that Trump, his National Security Adviser, his Attorney General, and his son-in-law failed to disclose – makes Gerth’s chief complaint about the NYT coverage look very different.

He appears especially peeved over a series of NYT stories in this same time period that described the sheer number of contacts that investigators were discovering with various Russians described by the paper as intelligence officers.

Gerth’s critique relies heavily on a Peter Strzok annotation of the February 14 story that Strzok shared with top FBI officials (parts of which, detailing how few call records the investigation had yet obtained, explain why early reports Gerth points to to make claims about the investigation, including one from James Clapper, are meaningless). It is absolutely true that Strzok found no basis for the NYT to claim that the Russians with whom Trump and his aides were in contact were Russian spies.

Gerth also reviews how Comey disavowed such reports in his public testimony to Congress, with support from Devin Nunes.

That section of the series, covering all four stories, is over 2,500 words long.

As Gerth described it, when NYT has been challenged on these stories, they’ve stood by them. I share Gerth’s curiosity regarding NYT’s sources for the stories, but like Gerth himself, the NYT is not about to share their sources.

It’s worth noting, though, that Gerth seems to believe that the US-based three letter agencies (or the Congressional personnel who’ve been briefed by those agencies) referenced in Strzok’s memo are the only possible sources for these stories. We know that at least five other intelligence services — the UK, the Dutch (from whom the US got a great deal of intelligence on the operation), the Spanish, the Ukrainians, and the Israelis — would have had their own views about which foreign interlocutors with Trump aides were spies. We know of a number of witnesses, not in government at all, who told Mueller they believed one or another interlocutor was a spy. We also know of a number of overt spies (such as Emirati ones) who had a role in the international effort to influence Trump. And we know of contacts – like that between Stone and Guccifer 2.0 – that were legitimately viewed as a spy contact when they started to become known around this time.

The clearest error in the NYT series pertains to the claim that an investigation into Stone had already been opened, but that’s an error SSCI seems to have shared, because on March 16, Senator Richard Burr told Don McGahn the FBI was investigating Paul Manafort, Roger Stone, Carter Page, and “Greek Guy.”

In the years since, however, the US government has come to believe more of the people known to have been interacting directly with Trump’s aides were Russian spies.

Konstantin Kilimnik — who along with at least two other Deripaska allies have been described as Russian agents in official US documents — is a particularly important one, given Gerth’s complaints that the NYT didn’t call Kilimnik for comment when the record shows they did (including in the March 3 one).

Gerth’s claims about the evidence that Kilimnik was a spy were nothing short of fanciful, including a perennial “Russiagate” favorite — which he credits to John Solomon’s scoop, from a period when Solomon was part of Rudy Giuliani’s outreach to people like Dmitry Firtash – that Kilimnik had been a source for the State Department.

As for Kilimnik possibly being a Russian spy, the only known official inquiry, by Ukraine in 2016, didn’t result in charges. More recent claims that he worked for the Russians, by the Senate intelligence panel in 2020 and the Treasury Department in 2021, offered no evidence. Conversely, there are FBI and State Department documents showing Kilimnik was a “sensitive source” for the latter. (The documents were disclosed a few years ago by John Solomon, founder of the Just the News website. Kilimnik, in an email to me, confirmed his ties with State.)

One primary objective of most spies, of course, is to infiltrate the agencies of other governments.

I asked CJR why Gerth claimed SSCI had no evidence against Kilimnik when their section substantiating their assessment about Kilimnik includes 16 bullet points, over half redacted, and they also included a separate 5-page, largely redacted section showing more fragmentary evidence that Kilimnik had a role in the hack-and-leak. I also asked why Gerth thought the FBI, under Trump, would have issued a $250,000 reward for Kilimnik’s arrest.

Those questions also went unanswered.

So the NYT may well have been ahead of the FBI’s assessment in spring 2017 (and their report that Stone was already part of the investigation has been shown to be wrong). But those reports really aren’t ahead of what the US intelligence community says they have since corroborated. Moreover, many of the Pulitzer stories that Gerth doesn’t mention show that Trump and his associates were aggressively lying to hide their ties to Russians or their interlocutors, and criminally so, in the case of Flynn and George Papadopoulos (and, ultimately, Michael Cohen and Roger Stone, too). That background — the lies that Flynn and Sessions and Kushner were telling about their Russian ties — is important background to these stories Gerth hates, yet he makes no mention of them.

Gerth’s main remaining gripe about the WaPo is even more remarkable. He spent six paragraphs on the WaPo’s scoop reporting the FISA order targeting Carter Page.

In early April, the Post story on Page landed, calling the surveillance “the clearest evidence so far that the FBI had reason to believe during the 2016 presidential campaign that a Trump campaign adviser was in touch with Russian agents. Such contacts are now at the center of an investigation into whether the campaign coordinated with the Russian government to swing the election in Trump’s favor.” It noted Page’s “effusive praise” for Putin and mentioned Schiff’s congressional recitation of the Page allegations in the dossier. Relying on anonymous sources, it gave a vague update on the dossier’s credibility: “some of the information in the dossier had been verified by US intelligence agencies, and some of it hasn’t.”

At the Times, the newsroom was irked about getting beaten by the Post. “Times is angry with us about the WP scoop,” Strzok texted to an FBI colleague, a few days later.

But the Post scoop was incomplete. Its anonymous sources mirrored the FBI’s suspicions but left out the bureau’s missteps and exculpatory evidence, as subsequent investigations revealed. It turns out that the secret surveillance of Page was an effort to bring in heavier artillery to an FBI inquiry that, in the fall of 2016, wasn’t finding any nefarious links, as the Times reported back then. Agents were able to review “emails between Page and members of the Donald J. Trump for President Campaign concerning campaign related matters,” according to an inquiry in 2019 by the Justice Department Inspector General. FBI documents show the surveillance of Page targeted four facilities, two email, one cell, and one Skype.

Still, even with the added surveillance capability, the investigation had not turned up evidence for any possible charges by the date of the Post piece, which came four days after the secret surveillance, called FISA, for the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, was renewed for the second time. (Page was never charged.)

The IG review also found that the FISA warrant process was deeply flawed. It relied heavily on the dossier, including the fabricated Millian allegation of a conspiracy, the IG found. Furthermore, the report said the warrants contained seventeen “significant errors and omissions,” such as leaving out exculpatory information about Page, including his previous work for the CIA and comments he made to an undercover FBI informant. And by the time of the Post piece, the dossier’s credibility was collapsing; the FBI knew the CIA called it “internet rumor,” and on its own the FBI “did not find corroboration for Steele’s election reporting,” according to the IG report.

The Post spokesperson, who would only speak on background, said the article on Page was “fair and accurate” and meant to reflect “how deeply the FBI’s suspicions were about Page.” They acknowledged the story was incomplete, noting that “at that time there was a lot that was not publicly known.” [my emphasis]

This passage commits several errors. The FBI targeted Page not because they were looking for heavier artillery. They did so because Page was about to travel internationally and they wanted coverage of that trip. (The FBI consistently described the FISA targeting of Page as “productive” or “fruitful.”) And Bill Barr’s DOJ didn’t withdraw the probable cause claim for Page’s first two FISA orders. The applications against him, which were based in part on his voluntary sharing of non-public information with known Russian intelligence officers, alleged he knowingly aided and abetted foreign spies.

Over time, there would be more than those four facilities, and in fact one main reason FBI submitted the especially problematic June 2017 application was because the FBI wanted to access financial information and two encrypted messaging apps, the latter out of suspicion that Page had destroyed a phone once he discovered he was under investigation.

Over time, there would be more than those four facilities, and in fact one main reason FBI submitted the especially problematic June 2017 application was because the FBI wanted to access financial information and two encrypted messaging apps, the latter out of suspicion that Page had destroyed a phone once he discovered he was under investigation.

The FBI also had concerns about Page’s initial denial in a March 16, 2017 interview that he had sought out some Russian official to identify himself as the Male-1 in court filings for one of the Russians trying to recruit him some years earlier.

There was evidence for possible charges; there was evidence when the FBI first opened an investigation into him in April 2016. Just not enough to charge him.

Errors aside, though, Gerth here adopts a fairly remarkable stance. He complains that the WaPo story confirming the FISA targeting did not include all the problems with the FISA applications that wouldn’t be discovered until much later. I spoke with a Congressional Republican who was privy to the applications targeting Page in summer 2018, for example, and even at that point, the person believed there was abundant other evidence against Page, even without any information from Steele. Crazier still, in April 2017 when the WaPo published that scoop, the worst abuse of all identified in the Page applications – the alteration of an email – hadn’t happened yet.

The WaPo would have needed a time machine to meet Gerth’s strictures.

Gerth’s claims that the NYT and WaPo’s reporting was particularly problematic are, with a few exceptions, extraordinarily weak, and that’s before you consider all the Pulitzer articles he simply ignored. But he also ignores some of the more problematic NYT stories, like the NYT decision to bury Trump’s discussion of adoptions with Putin immediately before he wrote a misleading note claiming the June 9 meeting addressed adoptions. Similarly, Gerth had no problem that the NYT not only parroted Bill Barr’s misleading March 24, 2019 letter about the Mueller Report, but ran entire blocks of his letter on the front page. I asked CJR if they had any problem with this article, which misrepresented court filings in the Manafort case to suggest that his sharing of polling data with Konstantin Kilimnik happened in the spring, not during the general election, and involved only Ukrainian oligarchs, not Deripaska; to this day, the article feeds misunderstanding about that allegation.

That was another question to which I got no answer.

Gerth has plenty of complaints about the NYT — just not about the stories where they erred on the side of downplaying the discoveries of the Russian investigation.

But as I’ll show in my next post, Gerth’s poor framing of his complaints about the NYT coverage doesn’t end there.

Links

CJR’s Error at Word 18

The Blind Spots of CJR’s “Russiagate” [sic] Narrative

Jeff Gerth’s Undisclosed Dissemination of Russian Intelligence Product

Jeff Gerth Declares No There, Where He Never Checked

“Wink:” Where Jeff Gerth’s “No There, There” in the Russian Investigation Went

My own disclosure statement

An attempted reconstruction of the articles Gerth includes in his inquiry

A list of the questions I sent to CJR