I want to further elaborate on a point in this post: It appears that David Weiss did not obtain a reliable warrant for the most showy evidence in his response motion to Hunter’s selective and vindictive prosecution claim until after he indicted Hunter for 3 gun felonies — indeed, he appears not to have obtained it until after Abbe Lowell asked for this kind of evidence.

I think it likely that, as a result, David Weiss will technically be relying on evidence from the laptop he obtained from John Paul Mac Isaac, which (as I’ll show in a follow-up), may be a particularly acute problem for the period in question.

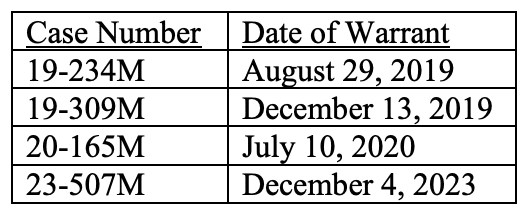

I’ve put a timeline below, relying on Weiss’ response motions on selective prosecution and discovery. Because Weiss did not provide dates for any of the warrants described in the former, I’ve noted the closest unsealed dockets before and after each warrant docket included to approximate the dates for those warrants.

The gun indictment, which Weiss obtained just before the statute of limitations expired, did not provide any proof that Hunter Biden was an addict when he purchased a gun on October 12, 2018. It simply stated, for each of three charges, that he knew he was.

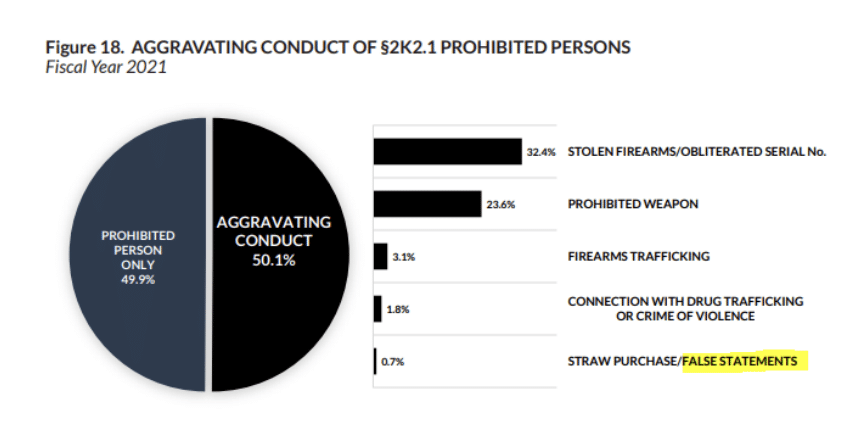

[T]he defendant, Robert Hunter Biden, provided a written statement on Form 4473 certifying he was not an unlawful user of, and addicted to, any stimulant, narcotic drug, and any other controlled substance, when in fact, as he knew, that statement was false and fictitious.

It’s true that on July 26, 2023, Hunter Biden admitted he was in treatment for addiction in Fall 2018 — but that admission was obtained with the promise of a diversion agreement — a point that Abbe Lowell noted in his motion to dismiss on immunity grounds.

Hunter was arraigned — initially with a 30-day deadline for pretrial motions — on October 3, 2023. At the hearing, Lowell said that he was going to ask for an evidentiary hearing, which (along with his TV appearances) would have alerted Weiss that he would seek to dismiss the indictment.

By Weiss’ own admission, he didn’t provide any discovery until October 12, four days after Abbe Lowell asked. He describes that that initial production, of just 350 pages, included “statements of the defendant including his admissions that he was addicted to crack cocaine and possessed a firearm in 2018,” electronic evidence from Hunter’s iCloud account, as well as “search warrants related to evidence the government may use in its case-in-chief.”

On October 12, 2023, the government provided to the defendant a production of materials consisting of over 350 pages of documents as well as additional electronic evidence from the defendant’s Apple iCloud account and a copy of data from the defendant’s laptop. This production included search warrants related to evidence the government may use in its case-in-chief in the gun case, statements of the defendant including his admissions that he was addicted to crack cocaine and possessed a firearm in 2018, and law enforcement reports related to the gun investigation. [my emphasis]

But he doesn’t say he provided all the warrants behind the evidence the government will use in its case-in-chief.

As I’ve noted, Hunter’s book is 272 pages long, so if Weiss included the book in that initial production, then there were only 78 other pages, to include warrants and law enforcement reports pertaining to the gun.

Among the things Lowell asked for in that initial discovery request was information “reflecting Mr. Biden’s sobriety in 2018” and “information reflecting Mr. Biden’s treatment for any substance or alcohol abuse in 2018.”

Weiss described that he provided evidence about payments to rehab programs in 2018 (this will include Keith Ablow!!!) on November 1.

On November 1, 2023, the government provided a production of materials to the defendant that was over 700,000 pages and largely consisted of documents obtained during an investigation into whether the defendant timely filed and paid his taxes and committed tax evasion. These documents included information of the defendant’s income and payments to drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs in 2018, the same year in which the defendant possessed the firearm while addicted to controlled substances.

Weiss didn’t describe providing any more information about Hunter’s addiction or sobriety.

Weiss didn’t describe providing any more discovery — and didn’t describe providing any more warrants at all — until January 9, almost a month after Lowell’s deadline for pretrial motions, including motions to suppress.

In advance of his initial appearance on the tax indictment, the government made a production of materials to the defendant on January 9, 2024, which included over 500,000 pages of documents and consisted of additional information related to the tax investigation.

Yet, by Weiss’ own admission, he never had a warrant to access iCloud content for gun charges — as opposed to tax and foreign influence charges — until he got it with District of Delaware Case No. 23-507M. If my approximations below are correct, Weiss didn’t obtain a warrant to search Hunter’s iCloud content for gun charges until sometime between November 30 and December 4 of last year. As noted previously, I asked Weiss’ spox to correct me if this was an error, but they declined to comment beyond what is in the filing.

Weiss is wildly squirrely about all this, as I’ll show. But he basically admits that he’s relying on that warrant — which it appears he obtained over two months after indicting Hunter — for the only evidence in this motion that shows Hunter’s drug use during the period he possessed the gun (and as noted, Weiss doesn’t describe when in 2023 the FBI first decided to send the gun to a lab for testing, but he admits it wasn’t until 2023).

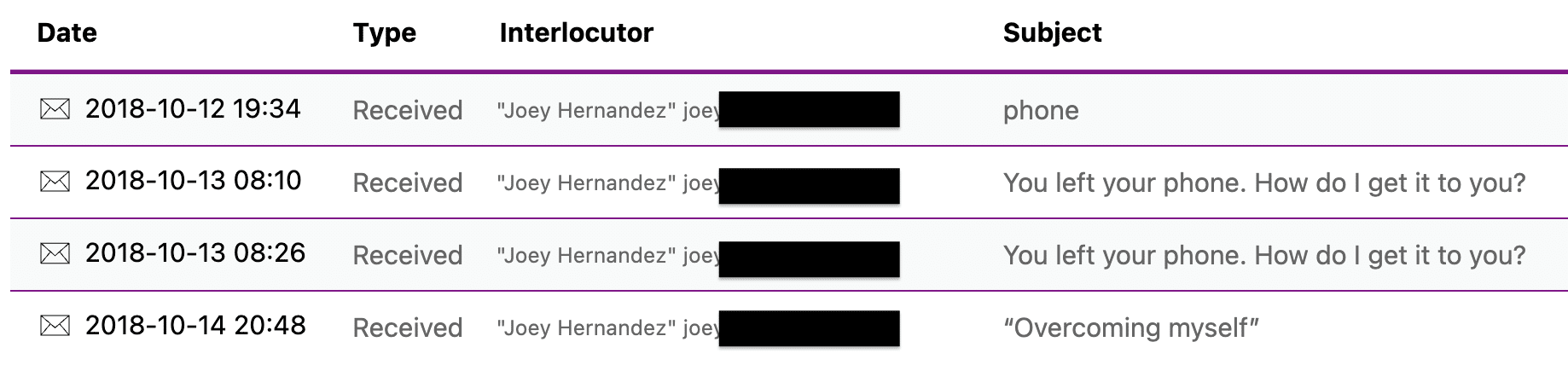

Prior to October 12, 2018 (the date of the gun purchase), the defendant took photos of crack cocaine and drug paraphernalia on his phone.

Also prior to his gun purchase, the defendant routinely sent messages about purchasing drugs.

On October 13, 2018, and October 14, 2018 (the day after and two days after he purchased the firearm), the defendant messaged his girlfriend about meeting a drug dealer and smoking crack. For example, on October 13, 2018, the defendant messaged her and stated, “. . . I’m now off MD Av behind blue rocks stadium waiting for a dealer named Mookie.” The next day, the defendant messaged her and stated, “I was sleeping on a car smoking crack on 4th street and Rodney.”

On October 23, 2018 (the day his then-girlfriend discarded his firearm), the defendant messaged his girlfriend and asked, “Did you take that from me [girlfriend]?” Later that evening, after his interactions with law enforcement, he messaged her about the “[t]he fucking FBI” and asked her, “so what’s my fault here [girlfriend] that you speak of. Owning a gun that’s in a locked car hidden on another property? You say I invade your privacy. What more can I do than come back to you to try again. And you do this???? Who in their right mind would trust you would help me get sober.” In response, the girlfriend stated “I’m sorry, I just want you safe. That was not safe. And it was open unlocked and windows down and the kids search your car. You have lost your mind hunter. I’m sorry I handled it poorly today but you are in huge denial about yourself and about that reality that I just want you safe. You run away like a child and blame me for your shit . . .”

Elsewhere in this response, Weiss quotes liberally from Hunter’s book, but the book really doesn’t say much about Hunter’s state in the 11 days he owned the gun.

I had returned that fall of 2018, after my most recent relapse in California, with the hope of getting clean through a new therapy and reconciling with Hallie.

Here’s how Weiss — in the paragraph immediately preceding this evidence — describes how — after Delaware cops had already seized the gun — investigators obtained evidence showing the purchase was illegal:

C. While Investigating the Defendant for Tax Violations, Investigators Obtained Evidence Showing His Prior Gun Purchase Was Illegal Because He Was Addicted to Controlled Substances

In August 2019, IRS and FBI investigators obtained a search warrant for tax violations for the defendant’s Apple iCloud account. 2 In response to that warrant, in September 2019, Apple produced backups of data from various of the defendant’s electronic devices that he had backed up to his iCloud account. 3 Investigators also later came into possession of the defendant’s Apple MacBook Pro, which he had left at a computer store. A search warrant was also obtained for his laptop and the results of the search were largely duplicative of information investigators had already obtained from Apple. 4 Law enforcement also later obtained a search warrant to search the defendant’s electronic evidence for evidence of federal firearms violations and to seize such data. 5

2 District of Delaware Case No. 19-234M and a follow up search warrant, District of Delaware Case Number 20-165M.

3 The electronic evidence referenced in this section was produced to the defendant in discovery in advance of the deadline to file motions.

4 District of Delaware Case No. 19-309M.

5 District of Delaware Case No. 23-507M

Weiss says he first obtained a warrant for Hunter’s iCloud account in August 2019, but that was just for tax violations. He doesn’t describe the temporal scope of that warrant. Joseph Ziegler predicated the investigation off a 2018 Suspicious Activity Report tied to payments to sex workers, but he only got approval for a criminal investigation by claiming — a claim that the tax indictment debunks — that no taxes were paid for his 2014 Burisma payments, so it’s possible that initial warrant only focused on 2014 and 2015 (particularly given that Hunter couldn’t have committed a tax crime in 2018 until October 2019, after that warrant was obtained in August 2019).

In a footnote but not in the text of the paragraph, Weiss mentions, oh, by the way, we got a follow-up warrant in 2020; he doesn’t provide the date, but it would have been between July 9 and 16, 2020. According to Gary Shapley, investigators obtained 2017 texts with that 2020 warrant — which again may suggest that Weiss didn’t obtain later content until after obtaining it first on the laptop.

Back in the main text, Weiss describes obtaining the laptop [bum bum BUM!!!]. But he claims that what he got from the laptop was “largely duplicative” of what he “already obtained” with the iCloud warrant.

Then, finally, he admits he never got a warrant to search the iCloud (he’s silent about the scope of the laptop warrants, but Ziegler only talked about tax and foreign influence peddling scopes) for evidence of gun crimes until that warrant that, if my approximation is correct, was after the indictment and after Weiss claimed to have provided all discovery for the gun crimes.

Note, significantly, that in a footnote Weiss said, “The electronic evidence referenced in this section was produced to the defendant in discovery in advance of the deadline to file motions,” but doesn’t say anything about when he provided that (apparent) December 2023 warrant to Lowell? It’s not clear whether Weiss included this among the iCloud and laptop material provided on October 12, or among the 700,000 pages provided on November 1.

But whichever it is, if I’m right about the timing of that gun crime warrant, Weiss did not yet have a warrant to access that material for the already obtained indictment yet. Lowell had the content, but not the notice that Weiss was going to use it for the gun crime.

And all this is before you consider the possibility that the second warrant, obtained in 2020, relied on the laptop (something that is consistent with Shapley’s testimony). If that’s the case, then Weiss would have a whole slew of other problems — not least, that John Paul Mac Isaac claims FBI was accessing the laptop before the date that Shapley says they got a warrant.

Update: Let me clarify why this matters. There’s no question that there was probable cause for gun crimes available for a warrant affidavit last year. And it is fairly common for prosecutors to get new warrants for content they’ve already seized; SDNY did so against both Michael Cohen and Rudy Giuliani, for example.

One reason this is problematic, though, is the timing. Weiss is arguing that he always intended to prosecute gun crimes, but he appears not to have gotten a warrant until after he charged it, which hurts his argument that he always intended to prosecute it (as does the delay in sending the gun to the lab). So it could hurt Weiss’ chances to win these motions.

Unless one of three things happened, David Weiss would be able to use this data at trial.

- If the warrant to obtain the 2018 data was the warrant obtained in 2020 and it relied on stuff from the laptop, the laptop may have tainted the 2020 warrant. There are several ways the laptop may have tainted the 2020 warrant, one of which is JPMI’s claim that FBI was accessing the laptop before they got a warrant.

- As noted, Weiss is really squirrely about when — or even if — it gave Abbe Lowell the warrant for this material. If they gave it to him after the deadline for these motions to suppress, it would mean they’ve deprived him of the ability to file a motion to suppress.

Timeline

August 22, 2019 [19-mj-232]

August 2019: Weiss first obtains iCloud data, for unstated dates, limited to tax crimes [19-mj-234]

In August 2019, IRS and FBI investigators obtained a search warrant for tax violations for the defendant’s Apple iCloud account. 2

2 District of Delaware Case No. 19-234M

August 27, 2019: [19-mj-235]

October 16, 2019: Mac Isaac’s father first contacts FBI [Shapley’s notes]

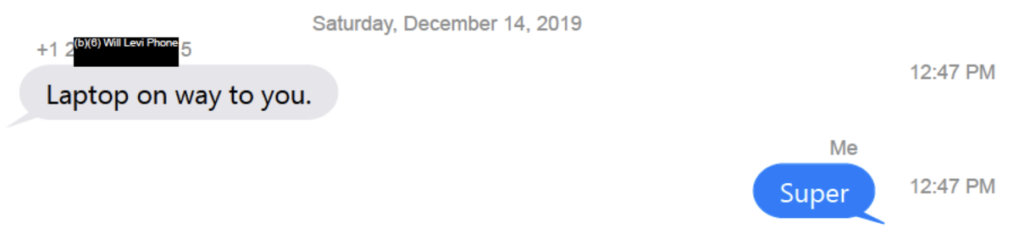

December 3, 2019: Ziegler first starts drafting search warrant for laptop

December 6, 2019: [19-mj-302]

December 9, 2019: FBI takes possession of laptop; per John Paul Mac Isaac, “Matt” called several times, asking for help accessing the machine, and revealing “we” had already tried to boot it up.

“Hi, it’s Matt again. So, we have a power supply and a USB-C cable, but when we boot up, I can’t get the mouse or keyboard to work.”

I couldn’t believe it—they were trying to boot the machine!

“The keyboard and trackpad were disconnected due to liquid damage. If you have a USB-C–to–USB-A adaptor, you should be able to use any USB keyboard or mouse,” I said. He related this to Agent DeMeo and quickly hung up.

Matt called yet again about an hour later.

“So this thing won’t stay on when it’s unplugged. Does the battery work?”

I explained that he needed to plug in the laptop and that once it turned on, the battery would start charging. I could sense his stress and his embarrassment at having to call repeatedly for help. [my emphasis]

December 12, 2019: Obtain OEO approval for warrant

December 13, 2019: Obtain warrant for laptop [date per Shapley]

Investigators also later came into possession of the defendant’s Apple MacBook Pro, which he had left at a computer store. A search warrant was also obtained for his laptop and the results of the search were largely duplicative of information investigators had already obtained from Apple.

4 District of Delaware Case No. 19-309M.

December 13, 2019: [19-mj-311]

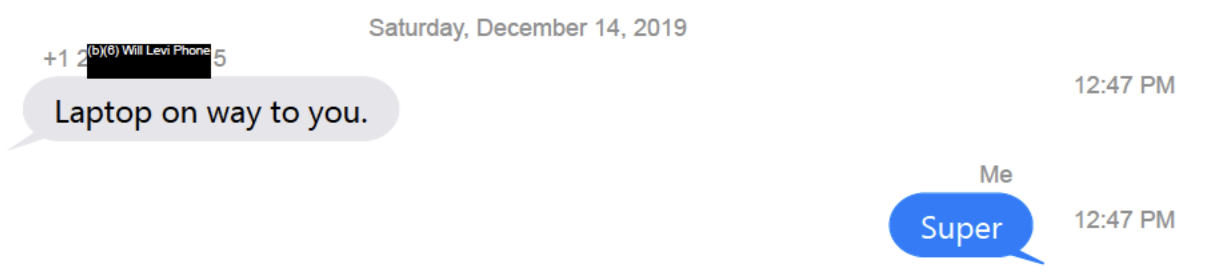

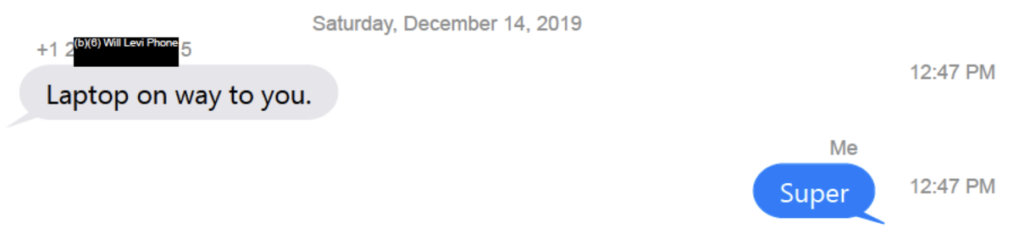

December 14, 2019: Will Levi sends Bill Barr text stating, “Laptop on way to you”

July 9, 2020: [20-mj-162]

July 2020: Weiss obtains follow-up warrant, by description still limited to tax crimes (but almost certainly also including foreign influence peddling) [20-mj-165]

In August 2019, IRS and FBI investigators obtained a search warrant for tax violations for the defendant’s Apple iCloud account. 2

2 and a follow up search warrant, District of Delaware Case Number 20-165M.

July 16, 2020: [20-mj-177]

ND, 2023: FBI first does lab tests on gun and finds cocaine residue

September 14, 2023: Gun indictment

October 3, 2023: Arraignment

October 8, 2023: Request for discovery

On October 8, 2023, the defendant made a request for discovery under Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure 16.

October 12, 2023: First discovery production

On October 12, 2023, the government provided to the defendant a production of materials consisting of over 350 pages of documents as well as additional electronic evidence from the defendant’s Apple iCloud account and a copy of data from the defendant’s laptop. This production included search warrants related to evidence the government may use in its case-in-chief in the gun case, statements of the defendant including his admissions that he was addicted to crack cocaine and possessed a firearm in 2018, and law enforcement reports related to the gun investigation. [my emphasis]

November 1, 2023: Discovery production 2

On November 1, 2023, the government provided a production of materials to the defendant that was over 700,000 pages and largely consisted of documents obtained during an investigation into whether the defendant timely filed and paid his taxes and committed tax evasion. These documents included information of the defendant’s income and payments to drug and alcohol rehabilitation programs in 2018, the same year in which the defendant possessed the firearm while addicted to controlled substances.

November 15, 2023: Follow-up request for discovery regarding Trump’s interference and Brady channel

November 15, 2023: Abbe Lowell requests subpoenas for Trump, Bill Barr, and others

November 30, 2023: [23-mj-504]

ND, 2023:

Law enforcement also later obtained a search warrant to search the defendant’s electronic evidence for evidence of federal firearms violations and to seize such data.5

5 District of Delaware Case No. 23-507M

December 4, 2023: [23-mj-508]

December 7, 2023: Tax indictment

December 11, 2023: Hunter’s motions due

ND: Third discovery production

In advance of his initial appearance on the tax indictment, the government made a production of materials to the defendant on January 9, 2024, which included over 500,000 pages of documents and consisted of additional information related to the tax investigation.

January 11, 2023: Arraignment