Two Views Of Protection Of Rights

The Supreme Court Has Always Been Terrible. In Chapter 2 of How Rights Went Wrong, Jamal Greene selects three examples of terrible cases: Dred Scott v. Sanford, Plessy v. Ferguson, and Lochner v. New York. These three cases are so blatantly horrible that no one can support their outcomes and be considered acceptable in academia. Or in polite society, if you ask me.

Greene sees Dred Scott as a case about who is entitled to rights under the Constitution.

At stake in Dred Scott were the boundaries of the political community entitled to the law’s protection and able to claim rights under it.

…

Chief Justice Roger Taney acknowledged that the Declaration of Independence had emphasized the “self-evident” truth “that all men are created equal.” But, Taney continued, “it is too clear for dispute, that the enslaved African race were not intended to be included, and formed no part of the people who framed and adopted this declaration.” P. 36.

Plessy is equally horrible. Henry Brown’s opinion says that being forced to travel in separate railcars isn’t a badge of inferiority but the “colored race” chooses to feel insulted.

Greene says that the Framers saw Constitutional rights as necessary to protect the rights granted by states and local governments from federal intrusion. On that theory, state and local majorities were free to grant or deny rights to people as they saw fit. The views of the Framers failed to protect people when those local majorities trampled on the rights of Black people and others. Local majorities can be just as tyrannical as any unaccountable monarch, and frequently are.

Reconstruction Era cases repurposed the 14th Amendment to protect capitalists from regulation by state and federal governments. Lochner is the example frequently given. The bakers of New York persuaded the legislature to pass health and safety laws concerning their work hours and other matters. Lochner sued, saying that the laws interfered with his right to contract, which he alleged was guaranteed by the Constitution. The holding, that the right to contract prevails over state and federal laws, lasted until the 1930s when Franklin Delano Roosevelt threatened to expand SCOTUS.

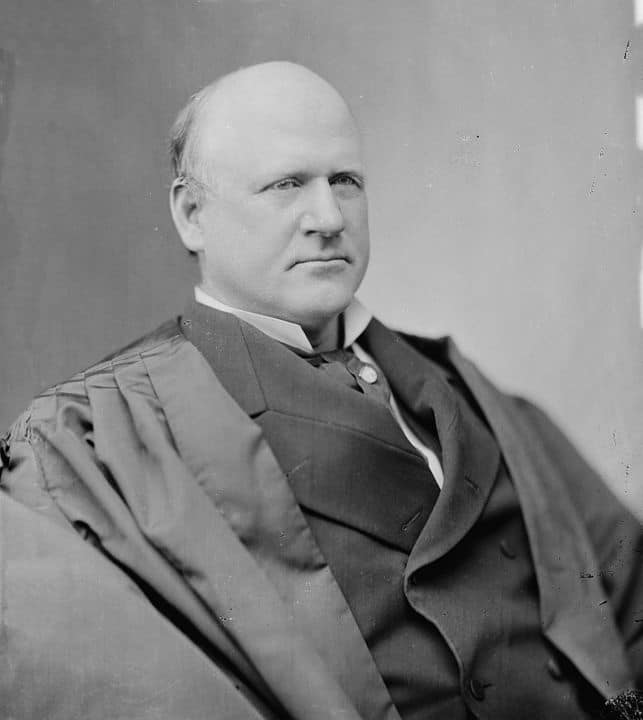

There were two dissents in Lochner, by Oliver Wendell Holmes and John Marshall Harlan. Holmes took the view that there are Constitutional rights, and these must be given maximum protection. But laws that do not implicate Constitutional rights are in the province of the legislature and must be respected and enforced by the courts.

For Holmes, the Constitution protected very few rights—and certainly not the right to contract—but those it protected, such as freedom of speech, it protected strongly. P. 54.

Harlan took the view that all rights, including those enumerated in the Constitution, must be respected. The question for courts is the extent to which rights are respected when they conflict with other rights or the rights of society. Harlan agrees that the Constitution protects the right to enter into contracts. But.

The right to contract “is subject to such regulations as the state may reasonably prescribe for the common good and the well-being of society.” P. 55.

The job of a court in a case like Lochner is not whether there is a Constitutional right to contract. It’s to determine whether the state is acting reasonably in regulating that right. Greene notes that it might have helped if the Courts had considered the right to labor, a right protected by political action .

Holmes’ views prevailed, for reasons we learn in Chapter 3. Greene sees this as the birth of what he calls “rightsism”, the fetish for rights that we see all the time now.

Discussion

1. I’ve skipped all the material that makes this chapter so persuasive. Greene gives detailed and clear descriptions of the cases, and of the backgrounds of Holmes and Harlan. This isn’t just a dry theoretical lecture, it’s a lively picture of important documents and the people who crafted them. It’s a good reminder that we are persuaded not just by logic but by the perceptions we have of the facts and issues in cases. I found myself persuaded that he was on the right track long before we got to the meat of the arguments.

2. I’ve tried to read Dred Scott and Plessy, but failed. The mindset of the writers is jarring even through the somewhat difficult language of that era. The bias is blatant. And yet I’m sure these judges were, in the words of William Baude about the current right-wing majority, “principled and sound”, with some blemishes.

Baude explains that all the recent controversial decisions “… rightly emphasized the importance of turning to historical understandings in deciding Constitutional cases rather than imposing modern policy views.” Of course, Dred Scott, Plessy, and Lochner are soundly reasoned and in accord with historical tradition. That’s not my idea of a good way to justify any Constitutional decision. Maybe it’s relevant that Baude is a member of the Federalist Society, the organization founded by Leonard Leo.

I discussed my view of good judging in this post. Start at “Let’s begin with this question” for the general discussion. Needless to say, it has nothing to do with anything taught by the conservative legal movement.

3. Lochner logic shows up in Project 2025’s Mandate for Leadership.

Hazard-Order Regulations. Some young adults show an interest in inherently dangerous jobs. Current rules forbid many young people, even if their family is running the business, from working in such jobs. This results in worker shortages in dangerous fields and often discourages otherwise interested young workers from trying the more dangerous job. With parental consent and proper training, certain young adults should be allowed to learn and work in more dangerous occupations. P. 595.

4. In The Nation That Never Was Kermit Roosevelt says that the meaning of the term “all men are created equal” changed through the efforts of Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass and many others. Greene does something similar with the idea of Constitutional rights. He explains the shift in our understanding of the Bill of Rights as protecting the power of the states from the central government, to our current view that it protects individuals from all government action.

Language and grammar change, sometimes quickly. So does our knowledge and understanding of history. That’s why originalism and textualism are suspect methods. I do not think the legal academy has given this enough attention.