The New I Con: “Total Number of Orders and Targets”

The I Con people, in another attempt to feign transparency, have announced they will release “new” numbers.

Consistent with this directive and in the interest of increased transparency, the DNI has determined, with the concurrence of the IC, that going forward the IC will publicly release, on an annual basis, aggregate information concerning compulsory legal process under certain national security authorities.

Specifically, for each of the following categories of national security authorities, the IC will release the total number of orders issued during the prior twelve-month period, and the number of targets affected by these orders:

- FISA orders based on probable cause ( Titles I and III of FISA, and sections 703 and 704).

- Section 702 of FISA

- FISA Business Records (Title V of FISA).

- FISA Pen Register/Trap and Trace ( Title IV of FISA)

- National Security Letters issued pursuant to 12 U.S.C. § 3414(a)(5), 15 U.S.C. §§ 1681u(a) and (b), 15 U.S.C. § 1681v, and 18 U.S.C. § 2709.

Only, this is, as I Con transparency always is, less than meets the eye.

To start with, the I Cons already release much of this due to statutory requirements. It releases the number of FISA orders on probable cause (and the number rejected), the number of business records, and the National Security letters, as well as the number of US persons included in those NSLs.

If I understand this correctly, the only thing new they’ll add to this information is the number of people “targeted” under the Section 215. In other words, they’ll tell us they’ve used fewer than 300 selectors in the previous year to conduct up-to three hop link analysis which in reality mean thousands or even millions might be affected (to say nothing of the hundreds of millions whose communications might be affected by virtue of being collected). But they won’t tell us how many people got included in those two or three hops.

Furthermore, in the absence of knowing what else they’re using Section 215 for, the meaning of these numbers will be hidden — as it already was when the government told us (last year) it had submitted 212 Section 215 applications, without telling us several of those applications collected every American’s phone records.

The same is true of the Pen Register/Trap and Trace provision. The government has told us they’re no longer using it to collect the Internet metadata of all Americans. But what are they using it to do? Are they (in one theory posited since the Snowden leaks started) using it to collect key information from Internet providers? Given the precedents hidden at the FISA Court, we’re best served to assume there is some exotic use like this, meaning any number they show us could represent a privacy threat far bigger than the number might indicate.

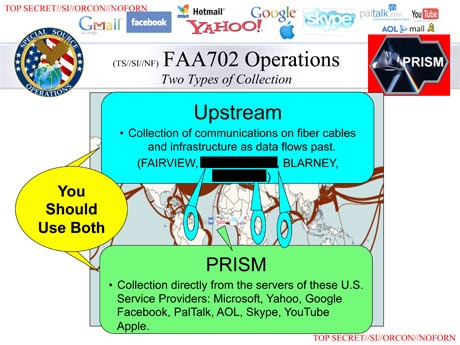

Then, finally, there’s Section 702, which will be new information. The October 3, 2011 John Bates opinion tells the NSA collects 250 million communications a year under Section 702; the August 2013 Compliance Assessment seems to support (though it redacts the numbers) the NSA targeting 63,000 to 73,000 selectors on any given day. In other words, those numbers are big. But that doesn’t tell us, at all, how many US persons get sucked up along with the targeted selectors. That number is one the NSA refuses to even collect, though Ron Wyden has asked them for it. Usually, when the NSA refuses to count something, it is because doing so would demonstrate how politically (and potentially, Constitutionally) untenable it is.

Moreover, the government doesn’t, apparently plan to release the number Google and Yahoo would like it to release, numbers which likely show how much more enthusiastic the well-lubricated telecoms are about providing this material than the less-well lubricated Internet providers. That is, the government isn’t going to (or hasn’t yet agreed to) provide numbers that show corporations have some leeway on how much of our data they turn over to the government.

So, ultimately, this seems to be about providing two or three new numbers, in addition to what the government is legally obliged to provide, yet without providing any numbers on how many Americans get sucked into this dragnet.

They will provide the “total number of orders and targets.” But they’re not going to provide the information we actually want to know.

![[graphic: Google Finance]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Graph_MSFT_10-YrChart_18JUL2013_500pxw1.jpg)

![[photo: liebeslakritze via Flickr]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/SpyGrafitti_liebeslakritze-Flickr_300pxw.jpg)