A Radical Proposal of Following the Law

Mieke Eoyang, the Director of Third Way’s National Security Program, has what Ben Wittes bills as a “disruptive” idea: to make US law the exclusive means to conduct all surveillance involving US companies.

But reforming these programs doesn’t address another range of problems—those that relate to allegations of overseas collection from US companies without their cooperation.

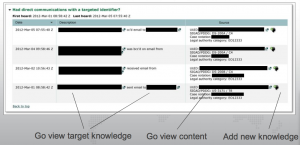

Beyond 215 and FAA, media reports have suggested that there have been collection programs that occur outside of the companies’ knowledge. American technology companies have been outraged about media stories of US government intrusions onto their networks overseas, and the spoofing of their web pages or products, all unbeknownst to the companies. These stories suggest that the government is creating and sneaking through a back door to take the data. As one tech employee said to me, “the back door makes a mockery of the front door.”

As a result of these allegations, companies are moving to encrypt their data against their own government; they are limiting their cooperation with NSA; and they are pushing for reform. Negative international reactions to media reports of certain kinds of intelligence collection abroad have resulted in a backlash against American technology companies, spurring data localization requirements, rejection or cancellation of American contracts, and raising the specter of major losses in the cloud computing industry. These allegations could dim one of the few bright spots in the American economic recovery: tech.

[snip]

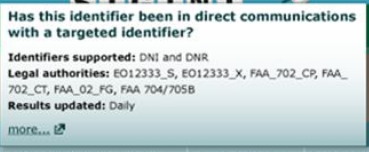

How about making the FAA the exclusive means for conducting electronic surveillance when the information being collected is in the custody of an American company? This could clarify that the executive branch could not play authority shell-games and claim that Executive Order 12333 allows it to obtain information on overseas non-US person targets that is in the custody of American companies, unbeknownst to those companies.

As a policy matter, it seems to me that if the information to be acquired is in the custody of an American company, the intelligence community should ask for it, rather than take it without asking. American companies should be entitled to a higher degree of forthrightness from their government than foreign companies, even when they are acting overseas.

Now, I have nothing against this proposal. It seems necessary but wholly inadequate to restoring trust between the government and (some) Internet companies. Indeed, it represents what should have been the practice in any case.

Let me first take a detour and mention a few difficulties with this. First, while I suspect this might be workable for content collection, remember that the government was not just collecting content from Google and Yahoo overseas — they were also using their software to hack people. NSA is going to still want the authority to hack people using weaknesses in such software, such as it exists (and other software companies probably still are amenable to sharing those weaknesses). That points to the necessity to start talking about a legal regime for hacking as much as anything else — one that parallels what is going on with the FBI domestically.

Also, this idea would not cover the metadata collection from telecoms which are domestically covered by Section 215, which will surely increasingly involve cloud data that more closely parallels the data provided by FAA providers but that would be treated as EO 12333 overseas (because thus far metadata is still treated under the Third Party doctrine here). This extends to the Google and Yahoo metadata taken off switches overseas. So, such a solution would be either limited or (if and when courts domestically embrace a mosaic theory approach to data, including for national security applications) temporary, because some of the most revealing data is being handed over willingly by telecoms overseas.