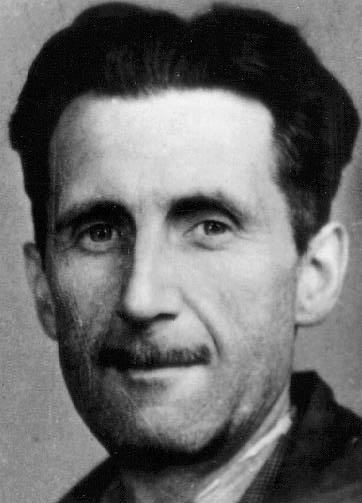

Did Eric Arthur Blair Come Back from Catalonia Radicalized?

The UK raised its threat limit to “pee your pants” today, based on the assessment an attack on the country is “highly likely.” This is a response to the 500 or so Britons who have gone to Syria and Iraq to fight with ISIS.

The UK raised its threat limit to “pee your pants” today, based on the assessment an attack on the country is “highly likely.” This is a response to the 500 or so Britons who have gone to Syria and Iraq to fight with ISIS.

PM David Cameron said at least 500 people had travelled from the UK “to fight in Syria and potentially Iraq”.

He said Islamic State (IS) extremists – who are attempting to establish a “caliphate”, or Islamic state, in the region – represented a “greater and deeper threat to our security than we have known before”.

New legislation would also be brought in to make it easier to take passports away from people travelling abroad to join the conflict, Mr Cameron said.

Which has me thinking — and not for the first time — of the large numbers of people who went to fight in the Spanish Civil War.

After all, it’s not like wanting to overthrow Bashar al-Assad is an ignoble goal. And while I think most Brits (and Americans) will grow disillusioned by the intolerance and ruthless discipline of ISIS, I can imagine the attraction, from afar, of moral certitude they offer. The 1930s, like today, are a morally confusing time, and those who fought the fascists in Spain ended up being vanguards of a necessary fight, even if they fought for an equally loathsome authoritarian force in the process.

The experience of fighting — and growing disillusioned — in Spain was chronicled by George Orwell in Homage to Catalonia. After his return, his views were suspect, but he did manage to return to the UK and warn of the dangers of absolutism.

I’m not the first to make this comparison. Boyd Tonkin wrote a piece in the Independent wondering whether those who traveled to Syria to fight Assad will be able to return to the UK without he specter of terrorism ruining their lives. (h/t to Gabe Moshenska who pointed me to it on Twitter)

Tony Blair’s third administration passed the Terrorism Act 2006. Section Five, as presently interpreted by the Crown Prosecution Service, makes it an offence to take part in military action abroad with a “political, ideological, religious or racial motive”. The legislation appears to forbid all training or action in a foreign combat. If so, its provisions would have criminalised every Briton who fought in Spain. It would have turned Lord Byron, whose commitment to Greek independence led him to arm and lead a raggle-taggle regiment prior to his death at Missolonghi in 1824, into an outlaw. As for the 6,500 veterans of Wellington’s armies who went off after Waterloo to fight against Spanish colonial rule in the battles that led to freedom for Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador, how could the courts have processed such a lawless throng?

The 2006 legislation currently targets UK citizens deemed to have fought with Syrian rebel groups. Estimates of their number vary wildly but a figure of around 400-500 has gained currency. At least eight have died. The fear of radicalisation, with any link to al-Qa’ida-allied units and above all to Isis treated as a communicable virus, has propelled the hard legal line. In January, 16 Britons were arrested after returning from Syria. Further arrests have followed since.

[snip]

[T]oday’s security-led prism and its “radicalisation” model, with the automatic penalties in place for any returnee, appears blind to every nuance. One British volunteer in Syria tweeted a poster that read “Keep Calm, Support Isis”: a spoof of the already much-parodied Second World War campaign to beef up morale. What are the chances that the kid who wrote that poster had watched Dad’s Army? Pretty high. If so, he will be many things apart from a bloodthirsty future avenger dedicated to importing holy mayhem on to British streets.

The long-term significance of an overseas adventure for anyone may not be apparent to them, or to others, at the time. But every present or past volunteer in Syria now knows they bear an invisible brand marked “potential murderer”, stamped by the agencies of surveillance. In a BBC radio analysis, one British fighter thought it a “slightly surreal” notion to “go back to the UK and start a jihad there”. For him, at least: “As to the global jihad, I couldn’t tell you if I’m going to be alive tomorrow, let alone future plans.”

Just because you hear someone rashly cry “wolf” does not mean that wolves do not exist. Over the past six weeks, Isis in Iraq has shown to the world a savagery almost beyond belief. Its bloody stunts may have emboldened a few would-be butchers. They will have deterred many secret faint-hearts, already in too deep. However, if the near-certainty of UK criminal sanctions closes down your road to reintegration, why not rise to the fanatics’ bait? What have you then got to lose?

I think that points to one real concern (thanks to the Intercept publication of the terrorist watchlist, we know anyone traveling to Syria without a known purpose will be treated as a terrorist). What will happen to those who traveled to fight Assad — who, after all, the US also considers a key enemy — but subsequently realized those fighting the war are equally loathsome? Will they have a way to come back and chronicle it for us, explain the dual threat, without being imprisoned as a terrorist?

I also think there’s a larger issue. Certainly since the Iraq War, but even just our larger approach to the war on terror — up to and including outsourcing some of our torture to Assad — the US has lost what moral high ground it might have once claimed. That is the cost of the last 10 years. Even its intervention in Erbil can more easily be explained by a need to protect Kurdish oil than the Yazidis. ISIS is surely going to increasingly play to that modeling our orange jumpsuits and waterboarding, to undercut our claims to exceptionalism.

I’m not advocating further US involvement. We’ve been selectively picking extremist thugs to support or oppose for so long, I can’t imagine how we’d ever reclaim the moral high ground.

But it seems necessary to recognize that there’s a draw to combatting evil completely separate from a draw to adopting Islamic extremism. And given the moral uncertainty of the day — caused in part by US complicity — I’m not sure what the outlet the US permits people.

The US is losing ground in an ideological fight for justice, and that’s significantly because of its own actions. Without realizing that, it’s not going to succeed against ISIS.