By chance of logistics, the men and women who have presided over a two decade war on Islamic terrorism are now presiding over the trials of those charged in January 6.

To deal with the flood of defendants, the Senior Judges in the DC District have agreed to pick up some cases. And because FISA mandates that at least three of the eleven FISA judges presiding at any given time come from the DC area, and because the presiding judge has traditionally been from among those three, it means a disproportionate number of DC’s Senior Judges have served on the FISA Court, often on terms as presiding judge or at the very least ruling over programmatic decisions that have subjected millions of Americans to collection in the name of the war on terror. Between those and several other still-active DC judges, over 60 January 6 cases will be adjudicated by a current or former FISA judge.

Current and former FISA judges have taken a range of cases with a range of complexity and notoriety:

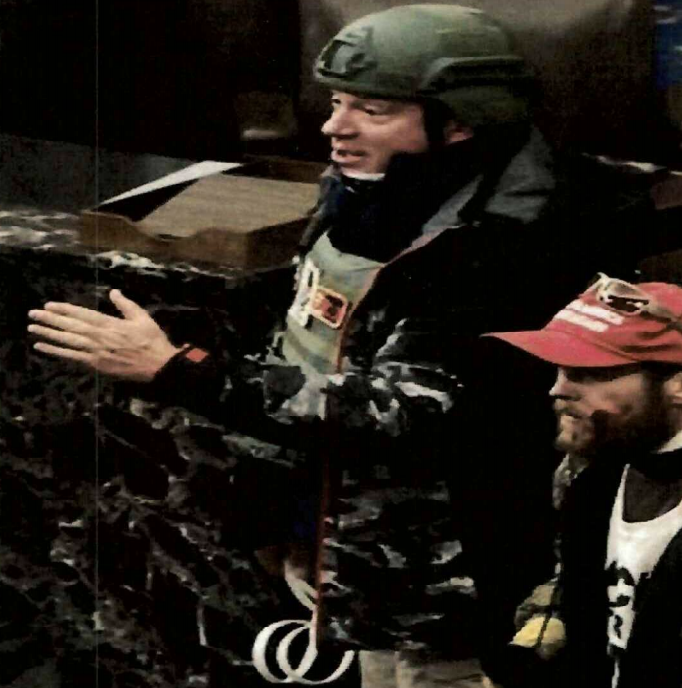

- Royce Lamberth served as FISC’s presiding judge from 1995 until 2002 and failed in his effort to limit the effect of the elimination of the wall between intelligence and criminal collection passed in the PATRIOT Act. And during a stint as DC’s Chief Judge he dealt with the aftermath of the Boumediene decision and fought to make the hard won detention reviews won by Gitmo detainees more than a rubber stamp. Lamberth is presiding over 10 cases with 14 defendants. A number of those are high profile cases, like that of Jacob Chansley (the Q Shaman), Zip Tie Guy Eric Munchel and his mother, bullhorn lady and mask refusenik Rachel Powell, and Proud Boy assault defendant Christopher Worrell.

- Colleen Kollar-Kotelly is still an active DC District judge, but she served as FISC presiding judge starting way back in 2002, inheriting the difficulties created by Stellar Wind from Lamberth. She’s the one who redefined “relevant to” in an effort to bring the Internet dragnet back under court review. She is presiding over ten January 6 cases with 12 defendants. That includes Lonnie Coffman, who showed up to the insurrection with a truck full of Molotov cocktails, as well as some other assault cases.

- John Bates took over as presiding judge of FISC on May 19, 2009. In 2010, he redefined “metadata” so as to permit the government to continue to use the Internet dragnet; the government ultimately failed to make that program work but FISC has retained that twisted definition of “metadata” nevertheless. In 2011, he authorized the use of “back door searches” on content collected under FISA’s Section 702. In 2013, Bates appears to have ruled that for Islamic terrorists, the FBI can get around restrictions prohibiting surveillance solely for First Amendment reasons by pointing to the conduct of an American citizen suspect’s associates, rather than his or her own. And while not a FISA case, Bates also dismissed Anwar al-Awlaki’s effort to require the government to give him some due process before executing him by drone strike; at the time, the government had presented no public evidence that Awlaki had done more than incite violence. Bates has eight January 6 cases with nine defendants (as well as some unrelated cases), but he is presiding over several high profile ones, including the other Zip Tie Guy, Larry Brock, the scion of a right wing activist family, Leo Bozell IV, and former State Department official Freddie Klein.

- Reggie Walton, who took over as presiding judge in 2013 but who, even before that, oversaw key programmatic decisions starting in 2008, showed a willingness both on FISC and overseeing the Scooter Libby trial to stand up to the Executive. That includes his extended effort to clean up the phone and Internet dragnet after Bush left in 2009, during which he even shut down part or all of the two dragnets temporarily. Walton is presiding over six cases with eight defendants, most for MAGA tourism.

- Thomas Hogan was DC District’s head judge in the 2000s. In that role, he presided over the initial Gitmo detainees’ challenges to their detention (though many of the key precedential decisions on those cases were made by other judges who have since retired). Hogan then joined FISC and ultimately took over the presiding role in 2014 and in that role, affirmatively authorized the use of Section 702 back door searches for FBI assessments. Hogan is presiding over 13 cases with 18 defendants, a number of cases involving multiple defendants (including another set of mother-son defendants, the Sandovals). The most important is the case against alleged Brian Sicknick assailants, Julian Khater and George Tanios.

- James Boasberg, who took over the presiding position on FISC on January 1, 2020 but had started making initial efforts to rein in back door searches even before that, is presiding over about eight cases with ten defendants, the most interesting of which is the case of Aaron Mostofsky, who is himself the son of a judge.

- Rudolph Contreras, who like Kollar-Kotelly and Boasberg is not a senior judge, is currently a FISC judge. He has six January 6 cases with seven defendants, most MAGA tourists accused of trespassing. There’s a decent chance he’ll take over as presiding judge when Boasberg’s term on FISC expires next month.

Of the most important FISA judges since 9/11, then, just Rosemary Collyer is not presiding over any January 6 cases.

Mind you, it’s not a bad thing that FISA judges will preside over January 6 cases. These are highly experienced judges with a long established history of presiding over other cases, ranging the gamut and including other politically charged high profile cases, as DC District judges do.

That said, in their role as FISA judges — particularly when reviewing programmatic applications — most of these judges have been placed in a fairly unique role on two fronts. First, most of these judges have been forced to weigh fairly dramatic legal questions, in secret, in a context in which the Executive Branch routinely threatens to move entire programs under EO 12333, thereby shielding those programs from any oversight by a judge. These judges responded to such situations with a range of deference, with Royce Lamberth and Reggie Walton raising real stinks and — the latter case — hand-holding on oversight over the course of most of a year, to John Bates and to a lesser degree Thomas Hogan, who often complained at length about abuses before expanding the same programs being abused. Several — perhaps most notably Kollar-Kotelly when she was asked to bring parts of Stellar Wind under FISA — have likewise had to fight to affirm the authority of the entire Article III branch, all in secret.

Ruling on these programmatic FISA applications also involved hearing expansive government claims about the threat of terrorism, the difficulty and necessity of identifying potential terrorists before they attack, and the efficacy of the secret programs devised to do that (the judges who also presided over Gitmo challenges, which includes several on this list, also fielded similar secret claims about the risk of terrorism). Some of those claims — most notably, about the efficacy of the Section 215 phone dragnet — were wildly overblown. In other words, to a degree unmatched by most other judges, these men and women were asked to balance the rights of Americans against secret government claims about the risks of terrorism.

Now these same judges are part of a group being asked to weigh similar questions, but about a huge number of predominantly white, sometimes extremist Christian, defendants, but to do so in public, with defense attorneys challenging their every decision. Here, the balance between extremist affiliation and First Amendment rights will play out in public, but against the background of a two decade war on terror where similar affiliation was criminalized, often in secret.

Generally, the District judges in these cases have not done much on the cases yet, as either Magistrates (on initial pre-indictment appearances) or Chief Judge Beryl Howell (on initial detention disputes) have handled some of the more controversial issues, and in a few cases, Ketanji Brown Jackson presided over arraignments before she started handing off cases in anticipation of her Circuit confirmation process.

But several of the judges have written key opinions on detention, opinions that embody how differently the conduct of January 6 defendants looks to different people.

Lamberth, for example, authored the original detention order for “Zip Tie Guy” Eric Munchel and his mom, Lisa Eisenhart. Even while admitting that Munchel made efforts to limit any vandalization during the riot, Lamberth nevertheless deemed Munchel’s actions a threat to our constitutional government.

The grand jury charged Munchel with grave offenses. In charging Munchel with “forcibly enter[ing] and remain[ing] in the Capitol to stop, delay, and hinder Congress’s certification of the Electoral College vote,” Indictment 1, ECF No. 21, the grand jury alleged that Munchel used force to subvert a democratic election and arrest the peaceful transfer of power. Such conduct threatens the republic itself. See George Washington, Farewell Address (Sept. 19, 1796) (“The very idea of the power and the right of the people to establish government presupposes the duty of every individual to obey the established government. All obstructions to the execution of the laws, all combinations and associations, under whatever plausible character, with the real design to direct, control, counteract, or awe the regular deliberation and action of the constituted authorities, are destructive of this fundamental principle, and of fatal tendency.”). Indeed, few offenses are more threatening to our way of life.

Munchel ‘s alleged conduct demonstrates a flagrant disregard for the rule of law. Munchel is alleged to have taken part in a mob, which displaced the elected legislature in an effort to subvert our constitutional government and the will of more than 81 million voters. Munchel’ s alleged conduct indicates that he is willing to use force to promote his political ends. Such conduct poses a clear risk to the community.

Defense counsel’s portrayal of the alleged offenses as mere trespassing or civil disobedience is both unpersuasive and detached from reality. First, Munchel’s alleged conduct carried great potential for violence. Munchel went into the Capitol armed with a taser. He carried plastic handcuffs. He threatened to “break” anyone who vandalized the Capitol.3 These were not peaceful acts. Second, Munchel ‘s alleged conduct occurred while Congress was finalizing the results of a Presidential election. Storming the Capitol to disrupt the counting of electoral votes is not the akin to a peaceful sit-in.

For those reasons, the nature and circumstances of the charged offenses strongly support a finding that no conditions of release would protect the community.

[snip]

Munchel gleefully entered the Capitol in the midst of a riot. He did so, the grand jury alleges, to stop or delay the peaceful transfer of power. And he did so carrying a dangerous weapon. Munchel took these actions in front of hundreds of police officers, indicating that he cannot be deterred easily.

Moreover, after the riots, Munchel indicated that he was willing to undertake such actions again. He compared himself-and the other insurrectionists-to the revolutionaries of 1776, indicating that he believes that violent revolt is appropriate. See Pullman, supra. And he said “[t]he point of getting inside the building is to show them that we can, and we will.” Id. That statement, particularly its final clause, connotes a willingness to engage in such behavior again.

By word and deed, Munchel has supported the violent overthrow of the United States government. He poses a clear danger to our republic.

This is the opinion that the DC Circuit remanded, finding that Lamberth had not sufficiently considered whether Munchel and his mother would pose a grave future threat absent the specific circumstances present on January 6. They contrasted the mother and son with those who engaged in violence or planned in advance.

[W]e conclude that the District Court did not demonstrate that it adequately considered, in light of all the record evidence, whether Munchel and Eisenhart present an identified and articulable threat to the community. Accordingly, we remand for further factfinding. Cf. Nwokoro, 651 F.3d at 111–12.

[snip]

Here, the District Court did not adequately demonstrate that it considered whether Munchel and Eisenhart posed an articulable threat to the community in view of their conduct on January 6, and the particular circumstances of January 6. The District Court based its dangerousness determination on a finding that “Munchel’s alleged conduct indicates that he is willing to use force to promote his political ends,” and that “[s]uch conduct poses a clear risk to the community.” Munchel, 2021 WL 620236, at *6. In making this determination, however, the Court did not explain how it reached that conclusion notwithstanding the countervailing finding that “the record contains no evidence indicating that, while inside the Capitol, Munchel or Eisenhart vandalized any property or physically harmed any person,” id. at *3, and the absence of any record evidence that either Munchel or Eisenhart committed any violence on January 6. That Munchel and Eisenhart assaulted no one on January 6; that they did not enter the Capitol by force; and that they vandalized no property are all factors that weigh against a finding that either pose a threat of “using force to promote [their] political ends,” and that the District Court should consider on remand. If, in light of the lack of evidence that Munchel or Eisenhart committed violence on January 6, the District Court finds that they do not in fact pose a threat of committing violence in the future, the District Court should consider this finding in making its dangerousness determination. In our view, those who actually assaulted police officers and broke through windows, doors, and barricades, and those who aided, conspired with, planned, or coordinated such actions, are in a different category of dangerousness than those who cheered on the violence or entered the Capitol after others cleared the way. See Simpkins, 826 F.2d at 96 (“[W]here the future misconduct that is anticipated concerns violent criminal activity, no issue arises concerning the outer limits of the meaning of ‘danger to the community,’ an issue that would otherwise require a legal interpretation of the applicable standard.” (internal quotation and alteration omitted)). And while the District Court stated that it was not satisfied that either appellant would comply with release conditions, that finding, as noted above, does not obviate a proper dangerousness determination to justify detention.

The District Court also failed to demonstrate that it considered the specific circumstances that made it possible, on January 6, for Munchel and Eisenhart to threaten the peaceful transfer of power. The appellants had a unique opportunity to obstruct democracy on January 6 because of the electoral college vote tally taking place that day, and the concurrently scheduled rallies and protests. Thus, Munchel and Eisenhart were able to attempt to obstruct the electoral college vote by entering the Capitol together with a large group of people who had gathered at the Capitol in protest that day. Because Munchel and Eisenhart did not vandalize any property or commit violence, the presence of the group was critical to their ability to obstruct the vote and to cause danger to the community. Without it, Munchel and Eisenhart—two individuals who did not engage in any violence and who were not involved in planning or coordinating the activities— seemingly would have posed little threat. The District Court found that appellants were a danger to “act against Congress” in the future, but there was no explanation of how the appellants would be capable of doing so now that the specific circumstances of January 6 have passed. This, too, is a factor that the District Court should consider on remand. [my emphasis]

The DC Circuit opinion (joined by Judith Rogers, who ruled for Gitmo detainees in Bahlul and a Boumediene dissent) was absolutely a fair decision. But it is also arguably inconsistent with the way that the federal government treated Islamic terrorism, in which every time the government identified someone who might engage in terrorism (often using one of the secret programs approved by this handful of FISA judges, and often based off far less than waltzing into the Senate hoping to prevent the certification of an election while wielding zip ties and a taser), the FBI would continue to pursue those people as intolerably dangerous threats. Again, that’s not the way it’s supposed to work, but that is how it did work, in significant part with the approval of FISA judges.

That is, with Islamic terrorism, the government treated potential threats as threats, whereas here CADC required Lamberth to look more closely at what could make an individual predisposed to an assault on our government — a potential threat — as dangerous going forward. Again, particularly given the numbers involved, that’s a better application of due process than what has been used for the last twenty years, but it’s not what happened during the War on Terror (and in weeks ahead, this will be relitigated with consideration of whether Trump’s continued incitement makes these defendants an ongoing threat).

Now compare Lamberth’s order to an order John Bates issued in the wake of and specifically citing the CADC ruling, releasing former State Department official Freddie Klein from pretrial detention. Klein is accused of fighting with cops in the Lower West Terrace over the course of half an hour.

Bates found that Klein, in using a stolen riot shield to push against cops in an attempt to breach the Capitol, was eligible for pre-trial detention, though he expressed skepticism of the government’s argument that Klein had wielded the shield as a dangerous weapon).

The Court finds that Klein is eligible for pretrial detention based on Count 3. Under the BRA, a “crime of violence” includes “an offense that has as an element of the offense the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another.” 18 U.S.C. § 3156(a)(4)(A). The Supreme Court in Johnson v. United States defined “physical force” as “force capable of causing physical pain or injury to another person.” 559 U.S. 133, 140 (2010); see also Def.’s Br. at 9.

[snip]

6 The Court has some doubts about whether Klein “used” the stolen riot shield as a dangerous weapon. The BRA does not define the term, but at least for purposes of § 111(b), courts have held that a dangerous weapon is any “object that is either inherently dangerous or is used in a way that is likely to endanger life or inflict great bodily harm.” See United States v. Chansley, 2021 WL 861079, at *7 (D.D.C. Mar. 8, 2021) (Lamberth, J.) (collecting cases). A plastic riot shield is not an “inherently dangerous” weapon, and therefore the question is whether Klein used it in a way “that is likely to endanger life or inflict great bodily harm.” The standard riot shield “is approximately forty-eight inches tall and twenty-four inches wide,” see Gov’t’s Br. at 13, and the Court disagrees with defense counsel’s suggestion that a riot shield might never qualify as a dangerous weapon, even if swung at an officer’s head, Hr’g Tr. 18:18–25, 19:1–11. See, e.g., United States v. Johnson, 324 F.2d 264, 266 (4th Cir. 1963) (finding that metal and plastic chair qualified as a dangerous weapon when “wielded from an upright (overhead) position and brought down upon the victim’s head”). But it is a close call whether Klein’s efforts to press the shield against officers’ bodies and shields were “likely to endanger life or inflict great bodily harm.” See Chansley, 2021 WL 861079, at *7.

But Bates ruled that there were certain things about the case against Klein — that he didn’t come prepared for combat, that he didn’t bring a weapon with him and instead just made use of what he found there, that any coordination he did involved ad hoc cooperation with other rioters rather than leadership throughout the event — that distinguished him from other defendants who (he suggested) should be detained, thereby limiting the guidelines laid out by CDC.

Bates’ decision on those points is absolutely fair. He has distinguished Klein from other January 6 defendants who, he judges, contributed more to the violence.

But there are two aspects of Bates’ decision I find shocking, especially from the guy who consistently deferred to Executive Authority on matters of national security and who sacrificed all of our communicative privacy in the service of finding hidden terrorist threats to the country. First, Bates dismissed the import of Klein’s sustained fight against cops because — he judged — Klein was only using force to advance the position of the mob, not trying to injure anyone.

The government’s contention that Klein engaged in “what can only be described as hand-to-hand combat” for “approximately thirty minutes” also overstates what occurred. See Gov’t’s Br. at 6. Klein consistently positioned himself face-to-face with multiple officers and also repeatedly pressed a stolen riot shield against their bodies and shields. His objective, as far as the Court can tell, however, appeared to be to advance, or at times maintain, the mob’s position in the tunnel, and not to inflict injury. He is not charged with injuring anyone and, unlike with other defendants, the government does not submit that Klein intended to injure officers. Compare Hr’g Tr. 57:12–18 (government conceding that the evidence does not establish Klein intended to injure anyone, only that “there was a disregard of care whether he would injure anyone or not” in his attempt to enter the Capitol), with Gov’t’s Opp’n to Def.’s Mot. to Reopen Detention Hearing & For Release on Conditions, ECF No. 30 (“Gov’t’s Opp’n to McCaughey’s Release”), United States v. McCaughey, III, 21-CR-040-1, at 11 (D.D.C. Apr. 7, 2021) (government emphasizing defendant’s “intent to injure” an officer who he had pinned against a door using a stolen riot shield as grounds for pretrial detention). And during the time period before Klein obtained the riot shield, he made no attempts to “battle” or “fight” the officers with his bare hands or other objects, such as the flagpole he retrieved. That does not mean that Klein could not have caused serious injury— particularly given the chaotic and cramped atmosphere inside the tunnel. But his actions are distinguishable from other detained defendants charged under § 111(b) who clearly sought to incapacitate and injure members of law enforcement by striking them with fists, batons, baseball bats, poles, or other dangerous weapons.

[snip]

Klein’s conduct was forceful, relentless, and defiant, but his confrontations with law enforcement were considerably less violent than many others that day, and the record does not establish that he intended to injure others. [my emphasis]

Bates describes that Klein wanted to use force in the service of occupying the building, not harming individual cops.

Of course, using force to occupy a building in service of halting the vote count is terrorism, but Bates doesn’t treat it as such.

Even more alarmingly, Bates flips how Magistrate Zia Faruqui viewed a government employee like Klein turning on his own government. The government had argued — and Faruqui agreed — that when a federal employee with Top Secret clearance attacks his own government, it is not just a crime but a violation of the Constitutional oath he swore to protect the country against enemies foreign and domestic.

Bates — after simply dismissing the import of Klein’s admittedly limited criminal history that under any other Administration might have disqualified him from retaining clearance — describes what Klein did as a “deeply concerning breach of trust.”

The government also argues that “Klein abdicated his responsibilities to the country and the Constitution” on January 6 by violating his oath of office as a federal employee to “support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic.” Id. at 24–25 (quoting 5 U.S.C. § 3331). The fact that, as a federal employee, Klein actively participated in an assault on our democracy to thwart the peaceful transfer of power constitutes a substantial and deeply concerning breach of trust. More so, too, because he had been entrusted by this country to handle “top secret” classified information to protect the United States’ most sensitive interests. In light of his background, Klein had, as Magistrate Judge Faruqui put it, every “reason to know the acts he committed” on January 6 “were wrong,” and yet he took them anyway. Order of Detention Pending Trial at 4. Klein’s position as a federal employee thus may render him highly culpable for his conduct on January 6. But it is less clear that his now-former employment at the State Department heightens his “prospective” threat to the community. See Munchel, 2021 WL 1149196, at *4. Klein no longer works for or is affiliated with the federal government, and there is no suggestion that he might misuse previously obtained classified information to the detriment of the United States. Nor, importantly, is he alleged to have any contacts—past or present—with individuals who might wish to take action against this country. [my emphasis]

Bates then argues that Klein’s ability to obtain clearance proves not that he violates oaths he takes (the government argument adopted by Faruqui), but that he has the potential to live a law-abiding life.

Ultimately, Klein’s history—including his ability to obtain a top-level security clearance—shows his potential to live a law-abiding life. His actions on January 6, of course, stand in direct conflict with that narrative. Klein has not—unlike some other defendants who have been released pending trial for conduct in connection with the events of January 6—exhibited remorse for his actions. See, e.g., United States v. Cua, 2021 WL 918255, at *7–8 (D.D.C. Mar. 10, 2021) (Moss, J.) (weighing defendant’s deep remorse and regret in favor of pretrial release). But nor has he made any public statements celebrating his misconduct or suggesting that he would participate in similar actions again. And it is Klein’s constitutional right to challenge the allegations against him and hold the government to its burden of proof without incriminating himself at this stage of the proceedings. See United States v. Lawrence, 662 F.3d 551, 562 (D.C. Cir. 2011) (“[A] district court may not pressure a defendant into expressing remorse such that the failure to express remorse is met with punishment.”). Hence, despite his very troubling conduct on January 6, the Court finds on balance that Klein’s history and characteristics point slightly toward release.

In short, Bates takes the fact that Klein turned on the government he had sworn to protect and finds that that act weighs in favor of release.

Bates judges that this man, whom he described as having committed violence to advance the goal of undermining an election, nevertheless finds that — having already done that — Klein does not pose an unmanageable prospective threat.

Therefore, although it is a close call, the Court ultimately does not find that Klein poses a substantial prospective threat to the community or any other person. He does not pose no continuing danger, as he contends, given his demonstrated willingness to use force to advance his personal beliefs over legitimate government objectives. But what future risk he does present can be mitigated with supervision and other strict conditions on his release.

Again, it’s not the decision itself that is troubling. It’s the thought process Bates used, both for the way Bates flips Klein’s betrayal of his oath on its head, and for the way that Bates views the threat posed by a man who already used force in an attempt to coerce a political end. And it’s all the more troubling knowing how Bates has deferred to the Executive’s claims about the nascent threat posed even by people who have not, yet, engaged in violence to coerce a political end.

Bates similarly showed no deference to the government’s argument that Larry Brock, a retired Lieutenant Colonel who also brought zip ties into the Senate chamber, should have no access to the Internet given really inflammatory statements on social media, including a call for “fire and blood” as early as November. Bates decided on his own that Probation could sufficiently monitor Brock’s Internet use, comparing Brock to (in my opinion) two unlike defendants to justify the decision. Again, the decision itself is absolutely reasonable, but for the guy who decided the government could monitor significant swaths of transnational Internet traffic out of a necessity to identify potential terrorists, for a guy who okayed the access of US person’s content with no warrant, it’s fairly remarkable that he hasn’t deferred to the government about the danger Brock poses on the Internet (to say nothing of Brock’s likely sophistication at evading surveillance).

Again, I’m not complaining about any of these opinions. The outcomes are all reasonable. It is genuinely difficult to fit the events of January 6 into our existing framework (and perhaps that’s a good thing). Plus, there is such a range of fact patterns that even in the Munchel opinion give force to the mob even while trying to adjudicate individuals’ actions.

But either because these discussions are public, or because we simply think about white person terrorism differently, less foreign, perhaps, than we do Islamic terrorism, the very same judges who’ve grappled with these questions for the past two decades don’t necessarily have the ready answers they had in the past.

FISA Judges January 6 cases

Lamberth:

- Jacob Chansley (resistance, obstruction, trespassing)

- Craig Bingert, Isaac Sturgeon, Taylor Johnatakis (obstruction, resisting, trespassing)

- Eric Munchel and Lisa Eisenhart (obstruction, abetting, and trespassing with weapon)

- Scott Fairlamb (obstruction, resisting/assault, trespassing with weapon)

- Chance and James Uptmore (trespassing)

- Anna Morgan-Lloyd (trespassing)

- Rachel Marie Powell (obstruction, destruction of government property, trespassing)

- Joseph Barnes (obstruction, trespassing)

- Frank Scavo (trespassing)

- Christopher Worrell (resisting, assault, trespassing with deadly weapon)

Kollar-Kotelly:

Bates:

Walton:

Hogan:

Boasberg:

Contreras: