Peter Baker, Meat Grinder for Bush

In the NYT, Peter Baker presents his version of George Bush’s decision not to pardon Scooter Libby as the best pitch for his new book, Days of Fire, Bush and Cheney in the White House. Given that the piece is not at all newsworthy (and as I’ll show, Baker’s version of it is badly flawed), I suppose Baker thought that Bush’s refusal to fulfill Cheney’s request supports Baker’s contention that Bush, not Cheney, was the dominant player in the relationship.

One piece of evidence Baker provides to support that contention is this quote from Alan Simpson.

Cheney “never did anything in his time serving George W. that George W. didn’t either sanction or approve of,” said Alan Simpson, a former Republican senator from Wyoming and a close friend of Cheney’s.

If Baker believes Simpson’s claim, however, then his entire reading of Cheney’s involvement in leaking Valerie Plame’s identity is wrong (and not just because he quotes Liz Cheney pretending PapaDick had no role in the leak).

Baker provides dialogue suggesting that Bush and certain lawyers — Baker identifies them as White House Counsel Fred Fielding and his Deputy William Burck — debated whether Libby was protecting Cheney.

“All right,” the president said when the lawyers concluded their assessment. “So why do you think he did it? Do you think he was protecting the vice president?”

“I don’t think he was protecting the vice president,” Burck said.

Burck figured that Libby assumed his account would never be contradicted, because prosecutors could not force reporters to violate vows of confidentiality to their sources. “I think also that Libby was concerned,” Burck said. “Because he took to heart what you said back then: that you would fire anybody that you knew was involved in this. I just think he didn’t think it was worth falling on the sword.”

Bush did not seem convinced. “I think he still thinks he was protecting Cheney,” the president said. If that was the case, then Cheney was seeking forgiveness for the man who had sacrificed himself on his behalf.

Baker implies that Bush’s conclusion — that Libby believed he was protecting Cheney — convinced himself it would not be ethical to pardon Libby based on Cheney’s insistence. (Note, whatever you and I were paying Burck, it was far too much, because his logic as portrayed here is pathetically stupid.)

That would imply that Bush believed — Burck’s shitty counsel to the contrary — that Cheney played some role in the leak.

But Alan Simpson, who truly does know Cheney well, says Cheney never did anything without either Bush’s sanction or approval. Which would imply that whatever Cheney did to leak Plame’s identity, he did with the approval of Bush.

Which brings us to the other gaping hole in Baker’s account (aside from his complete misunderstanding of the evidence surrounding the leak itself). Baker uses the word “lawyers” 11 times in this excerpt, including (but not limited to) the following.

In the final days of his presidency, George W. Bush sat behind his desk in the Oval Office, chewing gum and staring into the distance as two White House lawyers briefed him on the possible last-minute pardon of I. Lewis Libby.

“Do you think he did it?” Bush asked.

“Yeah,” one of the lawyers said. “I think he did it.”

[snip]

At the time, Bush said publicly that he was not substituting his judgment for that of the jury. So how would he explain a change of mind just 18 months later? That was the argument Ed Gillespie, the president’s counselor, made to Cheney when he came to explain why he was advising Bush against a pardon. “On top of that, the lawyers are not making the case for it,” Gillespie told Cheney, referring to the White House attorneys reviewing the case for Bush. “We’ll be asked, ‘Did the lawyers recommend it?’ And if the lawyers didn’t, it’s going to be hard to justify for the president.”

[snip]

The following Monday, Bush had his final, definitive meeting with the White House lawyers, ending any possibility of reconsideration. There would be no pardon for Libby. [my emphasis]

Lawyers lawyers lawyers. Baker emphasizes how important the counsel of Nixon’s old lawyer and his apparently half-witted deputy were to Bush’s decision, and he implies, with his description of which lawyers Ed Gillespie referred to, that those lawyers were limited to official White House lawyers.

Nowhere — at least nowhere in this excerpt — does Baker mention that Bush also consulted with his own lawyer, Jim Sharp, as reported by Time 4 years ago.

Meanwhile, Bush was running his own traps. He called Jim Sharp, his personal attorney in the Plame case, who had been present when he was interviewed by Fitzgerald in 2004. Sharp was known in Washington as one of the best lawyers nobody knew.

[snip]

While packing boxes in the upstairs residence, according to his associates, Bush noted that he was again under pressure from Cheney to pardon Libby. He characterized Cheney as a friend and a good Vice President but said his pardon request had little internal support. If the presidential staff were polled, the result would be 100 to 1 against a pardon, Bush joked. Then he turned to Sharp. “What’s the bottom line here? Did this guy lie or not?”

The lawyer, who had followed the case very closely, replied affirmatively.

Yet neither Time then nor Baker now considered the implications of Bush consulting with the lawyer who knew what questions he got asked when Pat Fitzgerald interviewed the President.

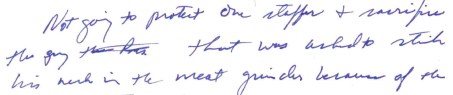

Those questions would have included whether — as Libby’s grand jury testimony recorded Cheney as having claimed — the President declassified the information, including Plame’s identity, Cheney ordered Libby to leak to Judy Miller. They also would have included why — as the note above shows — Cheney almost wrote that “the Pres” had ordered Libby to stick his neck in a meat grinder and rebut Joe Wilson, before he cross out the reference to the President and used the passive voice instead. They would have also included questions about Bush’s public comments about rebutting Wilson in meetings. (I laid out these details in this post.)

Peter Baker pretends that Bush had no personal knowledge of the leak or — more importantly — of Fitzgerald’s reasons for suspecting Cheney ordered the leak. He somehow forgets that Bush consulted his own lawyer, along with Fielding and Fielding’s lackey, either to interpret what Libby did or, more likely, what implications pardoning Libby would have for his own legal exposure.

Which is pretty bizarre. While including these details might make Bush look like a self-interested asshole, they are the only details that make sense if — as Baker suggests with the Simpson quote — whatever Cheney did that required Libby’s protection, he did with Bush’s sanction.