FISA Warranted Targets and the Phone Dragnet

The identifiers (such as phone numbers) of people or facilities for which a FISA judge has approved a warrant can be used as identifiers in the phone dragnet without further review by NSA.

From a legal standpoint, this makes a lot of sense. The standard to be a phone dragnet identifier is just Reasonable Articulable Suspicion of some tie to terrorism — basically a digital stop-and-frisk. The standard for a warrant is probable cause that the target is an agent of a foreign government — and in the terrorism context, that US persons are preparing for terrorism. So of course RAS already exists for FISC targets.

So starting with the second order and continuing since, FISC’s primary orders include language approving the use of such targets as identifiers (see ¶E starting on page 8-9).

But there are several interesting details that come out of that.

Finding the Americans talking with people tapped under traditional FISA

First, consider what it says about FISC taps. The NSA is already getting all the content from that targeted phone number (along with any metadata that comes with that collection). But NSA may, in addition, find cause to run dragnet queries on the same number.

In its End-to-End report submission to Reggie Walton to justify the phone dragnet, NSA claimed it needed to do so to identify all parties in a conversation.

Collections pursuant to Title I of FISA, for example, do not provide NSA with information sufficient to perform multi-tiered contact chaining [redacted]Id. at 8. NSA’s signals intelligence (SIGINT) collection, because it focuses strictly on the foreign end of communications, provides only limited information to identify possible terrorist connections emanating from within the United States. Id. For telephone calls, signaling information includes the number being called (which is necessary to complete the call) and often does not include the number from which the call is made. Id. at 8-9. Calls originating inside the United States and collected overseas, therefore, often do not identify the caller’s telephone number. Id. Without this information, NSA analysts cannot identify U.S. telephone numbers or, more generally, even determine that calls originated inside the United States.

This is the same historically suspect Khalid al-Midhar claim, one they repeat later in the passage.

The language at the end of that passage emphasizing the importance of determining which calls come from the US alludes to the indexing function NSA Signals Intelligence Division Director Theresa Shea discussed before — a quick way for the NSA to decide which conversations to read (and especially, if the conversations are not in English, translate).

Section 215 bulk telephony metadata complements other counterterrorist-related collection sources by serving as a significant enabler for NSA intelligence analysis. It assists the NSA in applying limited linguistic resources available to the counterterrorism mission against links that have the highest probability of connection to terrorist targets. Put another way, while Section 215 does not contain content, analysis of the Section 215 metadata can help the NSA prioritize for content analysis communications of non-U.S. persons which it acquires under other authorities. Such persons are of heightened interest if they are in a communication network with persons located in the U.S. Thus, Section 215 metadata can provide the means for steering and applying content analysis so that the U.S. Government gains the best possible understanding of terrorist target actions and intentions. [my emphasis]

Though, as I have noted before, contrary to what Shea says, this by definition serves to access content of both non-US and US persons: NSA is admitting that the selection criteria prioritizes calls from the US. And in the case of a FISC warrant it could easily be entirely US person content.

In other words, the use of the dragnet in conjunction with content warrants makes it more likely that US person content will be read.

Excluding bulk targets

Now, my analysis about the legal logic of all this starts to break down once the FISC approves bulk orders. In those programs — Protect America Act and FISA Amendments Act — analysts choose targets with no judicial oversight and the standard (because targets are assumed to be foreign) doesn’t require probable cause. But the FISC recognized this. Starting with BR 07-16, the first order approved (on October 18, 2007) after the PAA until the extant PAA orders expired, the primary orders included language excluding PAA targets. Starting with 08-08, the first order approved (on October 18, 2007) after FAA until the present, the primary orders included language excluding FAA targets.

Of course, this raises a rather important question about what happened between the enactment of PAA on August 5, 2007 and the new order on October 18, 2007, or what happened between enactment of FAA on July 10, 2008 and the new order on August 19, 2008. Read more →

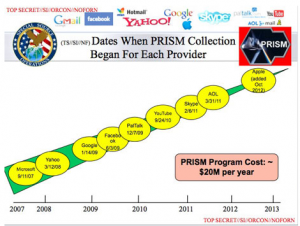

![[NSA presentation, PRISM collection dates, via Washington Post]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/WaPo_Prism-Slide5_06JUN2013_300pxw.jpg)

![[NSA presentation, title slide via Guardian-UK]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/GuardianUK_NSASlide_Prism-008_06JUN2013_300pxw.jpg)

![[NSA presentation, title slide, via Washington Post]](http://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/WaPo_Prism-Slide1_06JUN2013_300pxw1.jpg)