The Other Servers and Laptops FBI Never Investigated: VR Systems and North Carolina Polling Books

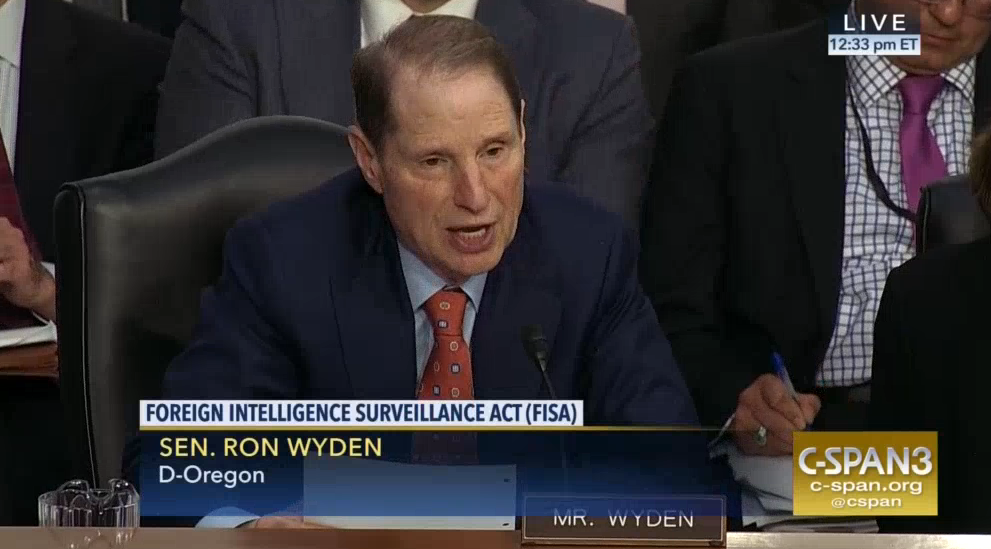

Ron Wyden had a lot to say in his minority views to the SSCI Report on election security released yesterday, mostly arguing that there need to be national standards and assistance and that no one can make any conclusions about the effects of Russia’s efforts in 2016 because no one collected the data to make such conclusions.

But there’s one line in his section raising questions about the 2016 conclusions I find particularly interesting, pertaining to VR Systems (which he doesn’t name).

Assessments about Russian attacks on the administration of elections are also complicated by newly public information about the infiltration of an election technology company.

Since the Mueller Report came out, Wyden has been trying to chase down this reference in the report to the VR Systems hack.

Unit 74455 also sent spear-phishing emails to public officials involved in election administration and personnel a~ involved in voting technology. In August 2016, GRU officers targeted employees of [redacted; VR Systems], a voting technology company that developed software used by numerous U.S. counties to manage voter rolls, and installed malware on the company network.

In May, he sent a letter to VR Systems President Mindy Perkins, asking how the company could claim, in March 2018, that it had not experienced a security breach when the report said it had been infected with malware in August 2016. In response, the company told Wyden (according to a letter he and Amy Klobuchar sent FBI Director Chris Wray) that they had alerted the FBI that they found suspicious IPs in their logs in real time, but that FBI had never explained the significance of that.

In a May 16, 2019, letter to Senator Wyden, VR Systems described how it participated in an August 2016 conference call with law enforcement. Participants in that call were apparently asked by the FBI to “be on the lookout for certain suspicious IP addresses.” According to VR Systems, the company examined its website logs, “found that several of the IP addresses had, in fact, visited our website” and as a result, the company “notified the FBI as we had been directed to do.” VR Systems indicates they did not know that these IP addresses were part of a larger pattern until 2017, which suggests the FBI may not have followed up with VR Systems in 2016 about the nature of the threat they faced.

The implication from Wyden’s letters is that VR Systems only hired FireEye to conduct an assessment of what happened after Reality Winner leaked an NSA document making it clear they had been targeted by GRU in 2017. [Update: Kim Zetter actually reported this here.]

In their June 12 letter, Wyden and Klobuchar asked Wray whether the FBI followed up on VR Systems’ report.

- What steps, if any, did the FBI take to examine VR Systems’ servers for evidence of a successful cyber breach after the company alerted the FBI, in August of 2016, to the presence of suspicious IP addresses in its website logs? If the FBI did not examine VR Systems’ servers or request access to those servers, please explain why.

- Several months after VR Systems first contacted the FBI, electronic pollbooks made by the company malfunctioned during the November 8 general election in Durham County, North Carolina. In the two and a half years since that incident in Durham County, has the FBI requested access to the pollbooks that malfunctioned, and the computers used to configure them, in order to examine them for evidence of hacking? If not, please explain why.

- VR Systems contracted FireEye to perform a forensic examination of its systems in the summer of 2017. Has the FBI reviewed FireEye’s conclusions? If so, what were its key findings?

It’s unclear how Wray answered (or didn’t). But just before Wyden sent this letter, the WaPo reported that no one had yet conducted a forensic examination of the laptops used in the VR Systems polling books in North Carolina. After Democrats took over control, they finally persisted in getting DHS to agree to check the laptops.

On Tuesday, the Department of Homeland Security told The Washington Post it will conduct a forensic analysis of the laptops used in Durham County elections in 2016. Lawson said North Carolina first asked the department to conduct such a review more than 18 months ago, though he added that DHS has generally been a “good partner” on election security.

“We appreciate the Department of Homeland Security’s willingness to make this a priority so the lingering questions from 2016 can be addressed in advance of 2020,” said Karen Brinson Bell, the newly appointed executive director of the State Board of Elections.

After the election, Durham County hired a firm called Protus3 to dig into what happened. The security consultant said it appeared the problems were caused by user error but ended its 12-page report with a list of recommendations that included examining computers in a lab setting and interviewing more election workers.

Durham County elections director Derek Bowens said he is comfortable with the report’s conclusions. Even so, in 2017, the county switched to electronic poll books created by the state. Bowens said in an interview that the state’s software would save money and is, in his view, better.

But for North Carolina officials, concerns resurfaced in June 2017 when the website Intercept posted a leaked National Security Agency report referencing “cyber espionage operations against a . . . U.S. company in August 2016.” The NSA report said that “it was likely that at least one account was compromised.”

VR Systems soon acknowledged that hackers had targeted the company but insisted that its network had not been breached.

North Carolina officials weren’t so sure.

“This was the first leak that indicated anything like a nation-state actor targeting a voting systems vendor,” Lawson said.

The state elections board soon launched its own investigation, seizing 40 laptops from Durham in July. And it suspended the certification that allowed more than 20 North Carolina counties to use VR Systems’ poll books during elections, an action that would later land in court. “Over the past few months there has been a considerable change in the election security landscape and the level of scrutiny we receive,” the board wrote in a letter explaining its decision to VR Systems.

No one working for the board had the technical expertise to do a forensic examination of the machines for signs of intrusion. Staffers asked DHS for technical help but did not get a substantive answer for a year and a half, Lawson said.

As noted, FireEye appears to have done an assessment at VR Systems itself in the wake of the Winner disclosure. The WaPo reports that FireEye declared VR Systems hadn’t been hacked, but wouldn’t share any information with Wyden or–apparently–DHS.

VR Systems said a cybersecurity firm it hired to review its computer network in 2017 found no evidence of a hack. A subsequent review by DHS also found no issues, the company said. VR Systems declined to give Wyden documentation of those reviews, citing the need to protect proprietary information.

Wyden in a statement to The Post accused VR Systems of “stonewalling congressional oversight.”

A senior U.S. official confirmed DHS’s review of VR Systems’s network to The Post and noted that by the time agency investigators arrived, a commercial vendor had already “swept” the networks. “I can’t tell you what happened before the commercial vendor came in there,” the official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to discuss a sensitive matter.

The same day as the WaPo report, Kim Zetter reported that VR Systems used remote updates for their software, opening up a possible point of compromise for hackers.

For two years, GRU hack denialists have thought it was the most important thing that the DNC provided FBI Crowdstrike’s forensic images of the hacked laptops, rather than providing the servers themselves.

But that step has, apparently, not been done yet with VR Systems. And the laptops that failed on election day are only now being forensically examined. Which is why, I presume, that Wyden believes it’s premature to claim no vote totals were affected on election day 2016.