On February 22, the Intercept had a thinly sourced story reporting (heavily relying on one “recently retired senior FBI official” whose motive and access weren’t explained and one other even less-defined source) on methods used in the January 6 investigation. It started by describing something unsurprising (some of which had been previously reported): that the FBI was using emergency legal authorities to conduct an investigation in the wake of an insurrection.

Using special emergency powers and other measures, the FBI has collected reams of private cellphone data and communications that go beyond the videos that rioters shared widely on social media, according to two sources with knowledge of the collection effort.

In the hours and days after the Capitol riot, the FBI relied in some cases on emergency orders that do not require court authorization in order to quickly secure actual communications from people who were identified at the crime scene. Investigators have also relied on data “dumps” from cellphone towers in the area to provide a map of who was there, allowing them to trace call records — but not content — from the phones.

From there, the story made conclusions that were not borne out by the evidence presented (which is not to say that such conclusions won’t one day be supported).

In particular, the story suggested that these investigative methods were used to investigate Congress, and likewise suggested that the involvement of Public Integrity prosecutors must mean members of Congress are already the focus of the investigation and further suggesting that the location data collection tied to the investigation of members of Congress.

The cellphone data includes many records from the members of Congress and staff members who were at the Capitol that day to certify President Joe Biden’s election victory.

[snip]

The Justice Department has publicly said that its task force includes senior public corruption officials. That involvement “indicates a focus on public officials, i.e. Capitol Police and members of Congress,” the retired FBI official said.

To make the insinuation, the story misstates the intent of a Sheldon Whitehouse statement aiming to use Congressional authorities to remove coup sympathizers from committees of jurisdiction (and ignores Whitehouse’s earlier statement that calls for the kind of data collection described in the story).

On January 11, Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., released a statement warning against the Justice Department getting involved in the investigation of the attack, at least regarding members of Congress, asserting that the Senate should oversee the matter.

Thus far, the story seems tailor-made to get Congress — the Republican members of which are already trying to sabotage the investigation — to start tampering with it.

Far down in the story, it also describes the orders used with more specificity — but not yet enough specificity to substantiate the claims made earlier in it.

Federal authorities have used the emergency orders in combination with signed court orders under the so-called pen/trap exception to the Stored Communications Act to try to determine who was present at the time that the Capitol was breached, the source said. In some cases, the Justice Department has used these and other “hybrid” court orders to collect actual content from cellphones, like text messages and other communications, in building cases against the rioters.

At the time I suggested the story’s conclusions went well beyond the evidence included in it. I had several concerns about the story.

First, it didn’t address the granularity of location data collected, explaining whether the data collection focused just on the Capitol building or (as the story claimed) “in the area” generally. The Capitol is, according to multiple experts, incredibly wired up, meaning that one can obtain a great deal of data specific to the Capitol building itself. That matters here, because as soon as Trump insurrectionists entered the Capitol building, they committed the trespass crimes charged against virtually all the defendants. And the people legally in the Capitol that day were largely victims and/or law enforcement. It’s not an exaggeration to say that anyone collected off location collection narrowly targeted to the Capitol building itself is either a criminal, a witness, or a victim (and often some mix of the three).

If location collection was focused on the Capitol building itself (we don’t know whether it was or not, and the reports of collection aiming to the find the person who left pipe-bombs in the neighborhood on January 5 do pose real cause for concern), it mitigates some of the concerns normally raised by the use of IMSI-catchers at public events and protests, which is that such location collection would include a large number of people who were just engaging in protected speech, as many of the people outside the Capitol were. Similarly, unlike with most geofence warrants or tower dumps, which are used to find possible leads for a crime, here, FBI had an overwhelming list of suspects from its mass of tips and video evidence already: it wasn’t relying on location data to find suspects. Plus, with normal geofence warrants and tower dumps, the vast majority of the data obtained comes from uninvolved people, posing a risk that those unrelated people could become false positives who, as a result, would get investigated closely. Here, again, anyone collected from location data inside the Capitol was by definition associated with the crime, either as witness, victim, or perpetrator.

Finally, the story not only didn’t rely on, but showed little familiarity with the hundreds of arrest affidavits released so far, which provide some explanation (albeit undoubtedly parallel constructed) for how the FBI built cases against those hundreds of people.

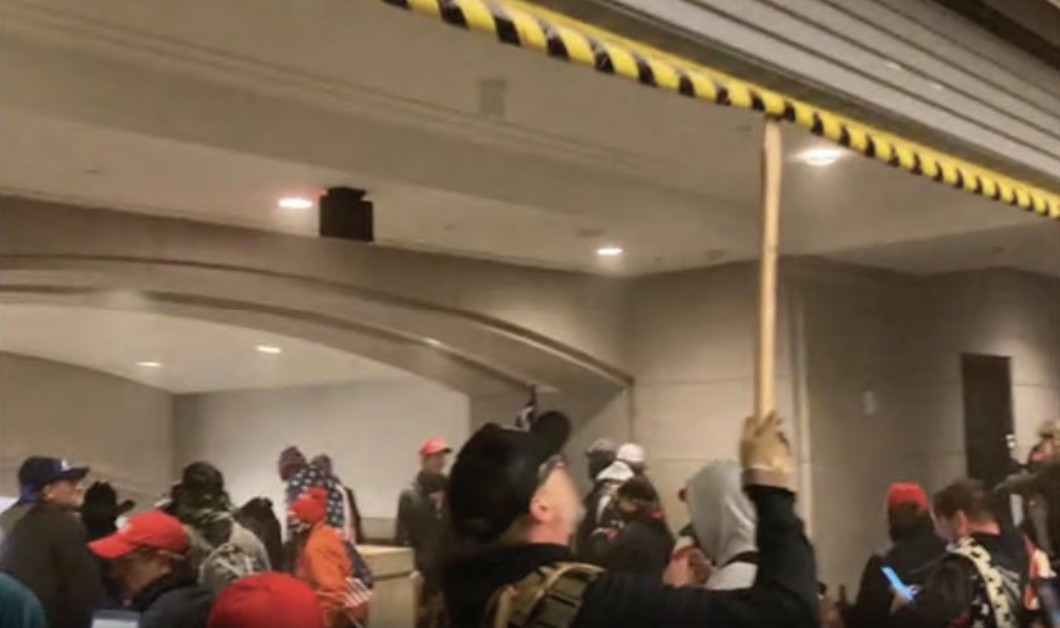

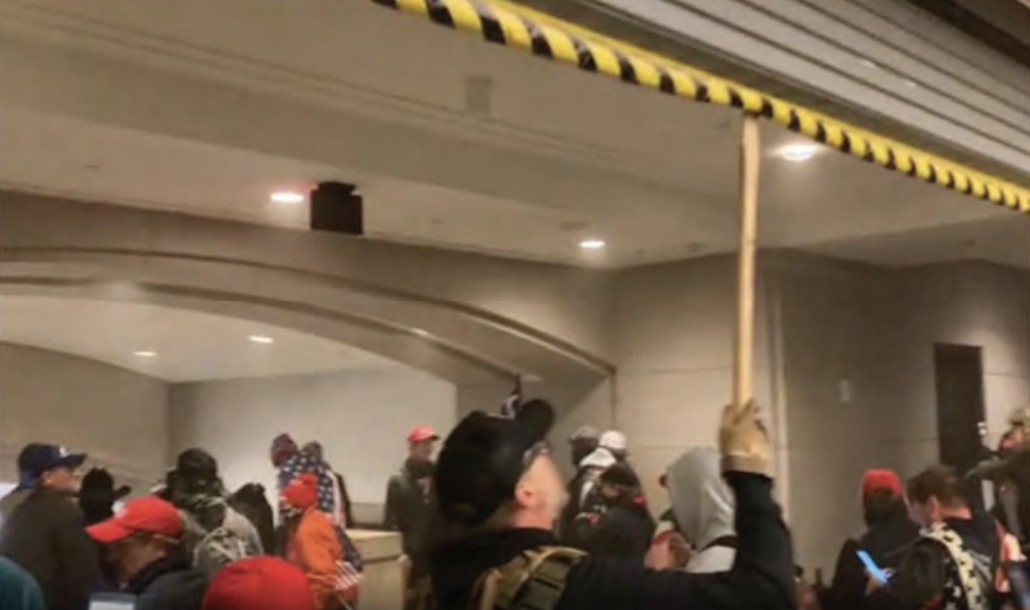

Well before The Intercept article was written, there were a few interesting techniques revealed in the affidavits. Perhaps the most interesting (and not specifically covered in The Intercept article, unless as a hybrid order) described identifying Christopher Spencer from the livestreams on Facebook he posted from inside the Capitol.

The government received information as part of a search warrant return that Facebook UID 100047172724820 was livestreaming video in the Capitol during these events. The government also received subscriber information for Facebook UID 100047172724820 in response to legal process served on Facebook. Facebook UID 100047172724820 is registered to Chris Spencer (“SPENCER”). SPENCER provided subscriber information, including a date of birth; current city/state, and a phone number to Facebook to create the account.

[snip]

The government received three livestream videos from SPENCER’s Facebook UID 100047172724820 as part of a search warrant return. At different times during the videos, Spencer either used the rear facing camera to show himself talking, or turned the phone toward his face. Your affiant would note that the camera is capturing a reversed image of SPENCER in two of these sections of video as evidenced by the text on SPENCER’s hat. As such, reversed images are also provided below the original screenshot [my emphasis]

The first mention of the Facebook return appears before a paragraph describing an associate of Spencer’s who had seen the videos and recognized his wife, and the later paragraph describes the associate sharing a phone number for Spencer that the FBI seemed to have already received from Facebook. As written (and this structure is matched in the affidavit for Spencer’s wife, Jenny) the narrative may indicate that the FBI obtained the Facebook return before the tip and identified Spencer from the Facebook return even before receiving the tip. This is one of the strongest pieces of evidence that the FBI used data obtained from location-based collection in the Capitol from any social media source to identify an unknown subject. But, as described, it also has some protections built in. The data was obtained with a warrant, not PRTT or d-order. That means the FBI would have had to show probable cause to obtain the content (but, for the reasons I explained above, most people in the Capitol live-streaming were committing a crime). There’s also no indication here that this video was privately posted (though with a warrant the FBI would be able to obtain such videos).

All this is a read of what this paragraph might suggest about data collection. It doesn’t describe whether the data was obtained via a particularized warrant (targeting just Spencer), or whether the FBI asked Facebook to provide all live-streaming posted from within the Capitol during the insurrection (there are other early affidavits that targeted the content of Facebook via individualized warrants). In Spencer’s case, I suspect it’s the latter (there’s nothing that remarkable about Spencer’s video, except he was outside Speaker Pelosi’s office). Even so, for most people, posting from inside the Capitol during the insurrection would amount to probable cause the person was trespassing.

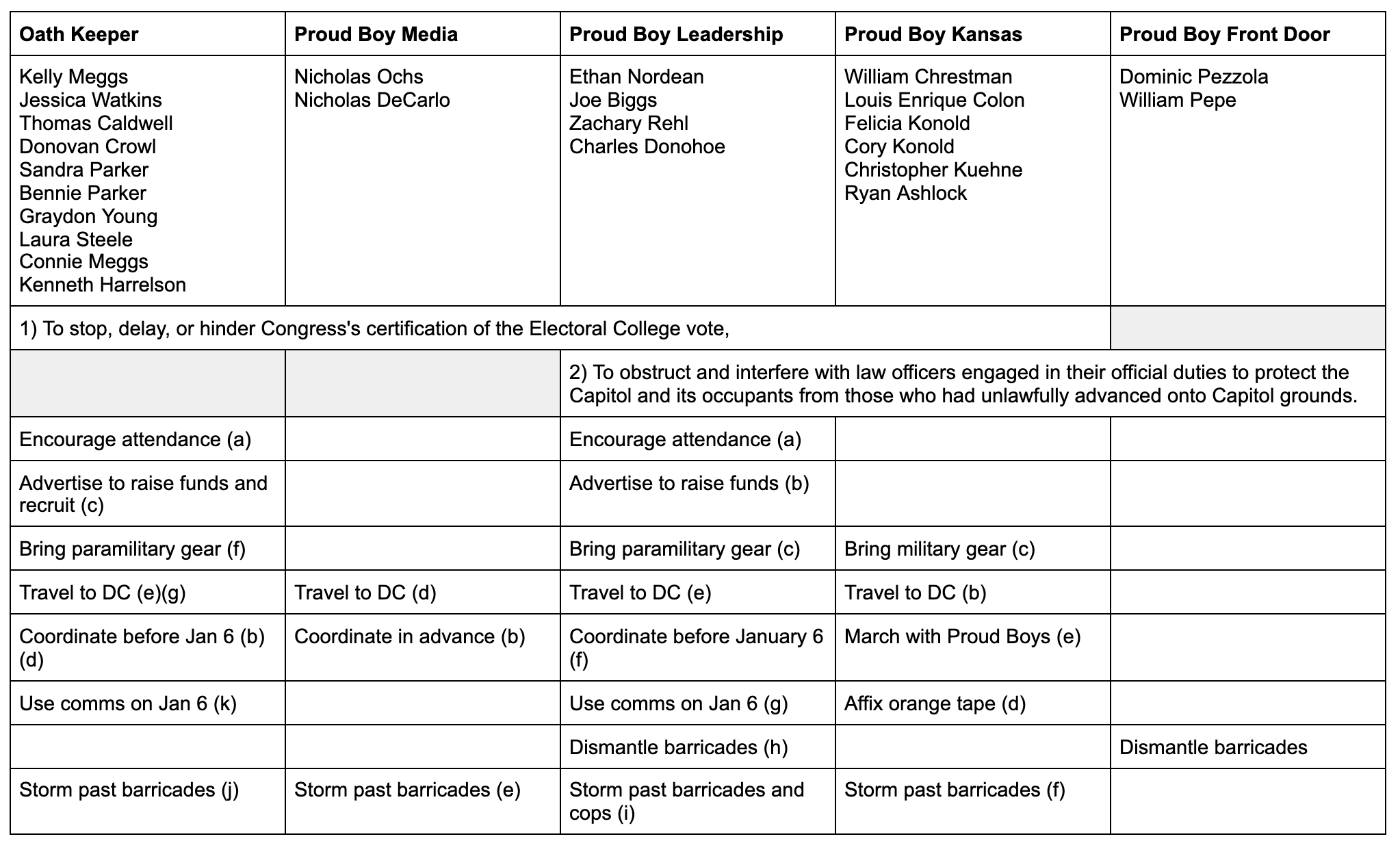

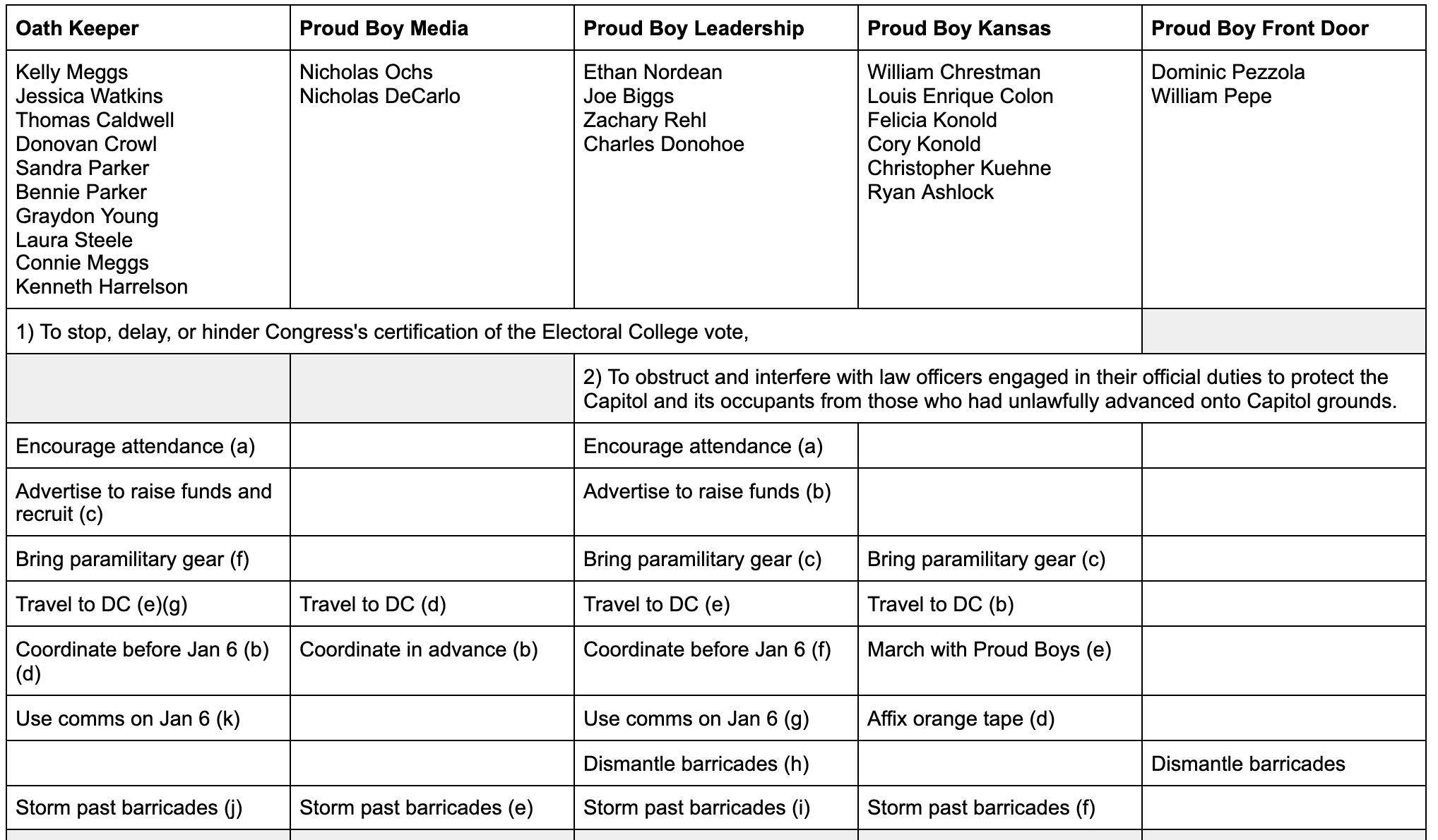

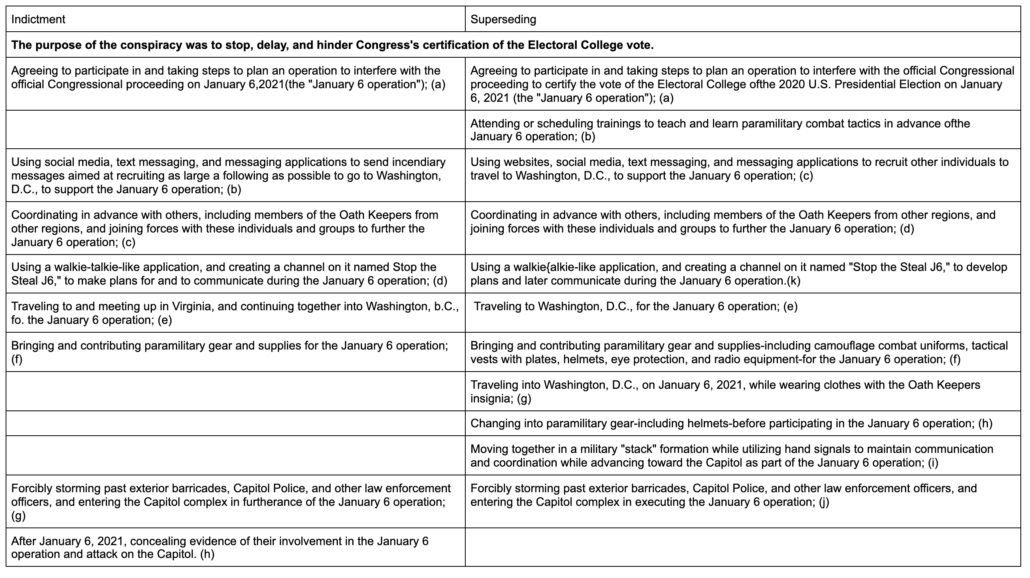

Even before The Intercept piece was posted I had also pointed to the affidavit for the Kansas cell of the Proud Boys. It uses location data to place one after another of the suspects “in or around” the Capitol during the insurrection: cell site data showed that the phones of Christopher Kuehne, Louis Colon, Felicia Konold were “in or around” the Capitol during the insurrection. That of Cory Konold, Felicia’s brother, was not shown to be, but,

Lawfully-obtained cell site records indicated that the FELICIA KONOLD cell called a number associated with CORY KONOLD while in or around the Capitol on January 6, 2021.

The most interesting detail in that affidavit pertained to William Chrestman. His phone wasn’t IDed off a cell site. Rather, it was IDed by connecting to Google services “in or around” the Capitol.

According to records produced by CHRESTMAN’s wireless cell phone provider in response to legal process, CHRESTMAN is listed as the owner of a cell phone number (“CHRESTMAN cell”). Lawfully-obtained Google records show that a Google account associated with the CHRESTMAN cell number was connected to Google services and was present in or around the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021.

A more recent document — the complaint against the southern Oath Keepers obtained on February 11 but unsealed long after that — describes the phones of those suspects in an area “includ[ing]” (but not necessarily limited to) the interior of the Capitol.

having utilized a cell site consistent with providing service to the geographic area that includes the interior of the United States Capitol building.

Unlike Spencer, the use of location data in the Proud Boys and Oath Keeper complaints seems to be used to establish probable cause. In both the militia group cases, the individuals appear to have been identified via different means (unsurprisingly, given their flamboyantly coordinated actions), with the location data being used in the affidavit to flesh out probable cause. (Undoubtedly, the FBI exploited this information far more thoroughly in an effort to map out other co-conspirators, but it is equally without doubt that the FBI had adequate probable cause to do so.)

The other day, DOJ unsealed an affidavit — that of Jeremy Groseclose — that provides more detail about the location collection at the Capitol. The FBI describes identifying Groseclose off of two tips, both on January 7, from people who had seen him post about being in the Capitol on Facebook (and in one case, remove his Facebook posts after he posted them).

Groseclose wore a gas mask for much of the time he was inside the Capitol (though wore the same clothes as he had outside), which undoubtedly made it more difficult to prove he was the person illegally inside the Capitol preventing cops from ousting the rioters.

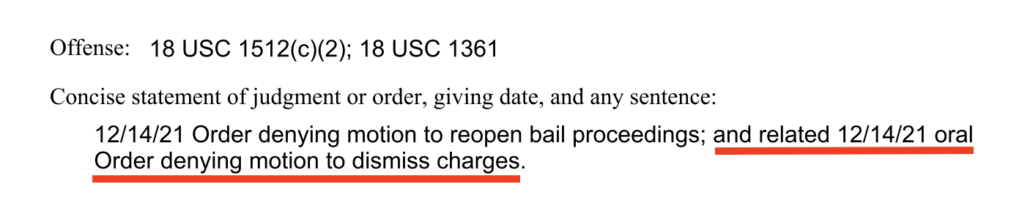

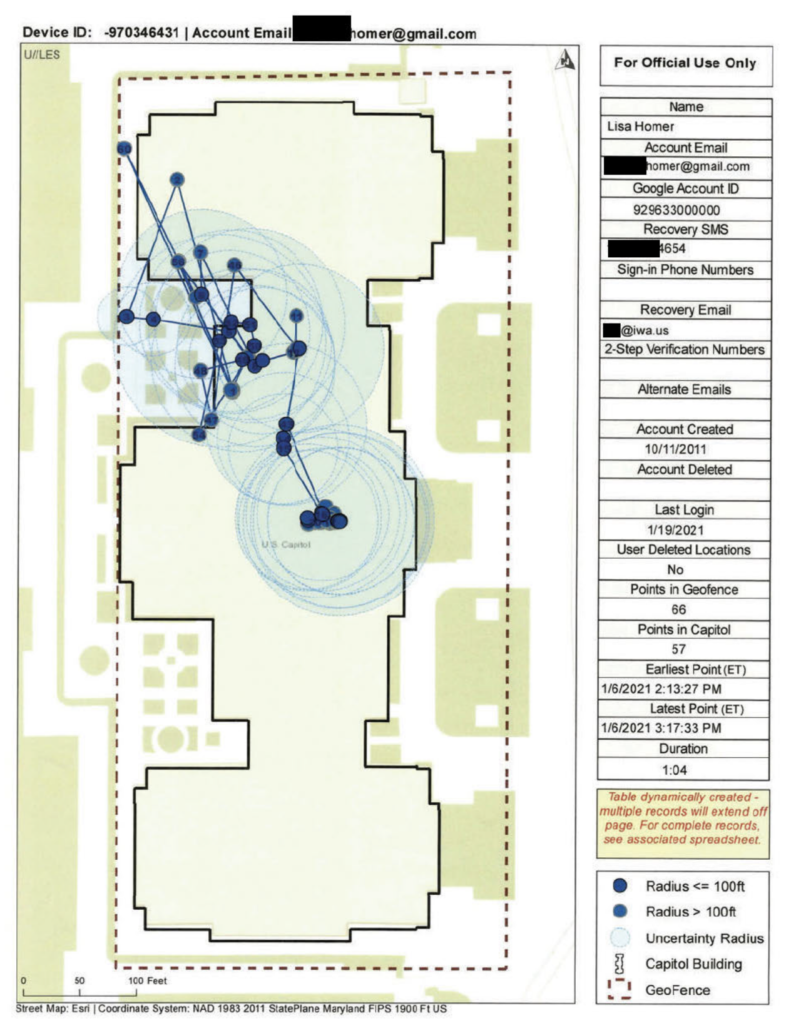

The FBI affidavit describes times when Groseclose appears on security footage from inside the Capitol without the gas mask, but doesn’t include it. To substantiate his presence in the Capitol, the FBI included three paragraphs describing what must be a Google geofence warrant showing the device identifiers for everyone within a certain geographic area.

According to records obtained through a search warrant served on Google, a mobile device associated with [my redaction]@gmail.com was present at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. Google estimates device location using sources including GPS data and information about nearby Wi-Fi access points and Bluetooth beacons. This location data varies in its accuracy, depending on the source(s) of the data. As a result, Google assigns a “maps display radius” for each location data point. Thus, where Google estimates that its location data is accurate to within 10 meters, Google assigns a “maps display radius” of 10 meters to the location data point. Finally, Google reports that its “maps display radius” reflects the actual location of the covered device approximately 68% of the time. In this case, Google location data shows that a device associated with [my redaction]@gmail.com was within the U.S. Capitol at coordinates associated with the center of the Capitol Building, which I know includes the Rotunda, at 2:56 p.m. Google records show that the “maps display radius” for this location data was 34 meters.

Law enforcement officers, to the best of their ability, have compiled a list (the “Exclusion List”) of any Identification Numbers, related devices, and information related to individuals who were authorized to be inside the U.S. Capitol during the events of January 6, 2021, described above. Such authorized individuals include: Congressional Members and Staffers, responding law enforcement agents and officers, Secret Service Protectees, otherwise authorized governmental employees, and responding medical staff. The mobile device associated with [my redaction]@gmail.com is not on the Exclusion List. Accordingly, I believe that the individual possessing this device was not authorized to be within the U.S. Capitol Building on January 6, 2021. Furthermore, surveillance footage from the Rotunda, time-stamped within a minute of 2:56 p.m., shows GROSECLOSE, in his distinctive clothing, using his cell phone in an apparent attempt to take a picture.

Records provided by Google revealed that the mobile device associated with [my redaction]@gmail.com belonged to a Google account registered in the name of “Jeremy Groseclose.” The Google account also lists a recovery SMS phone number that matches [my redaction]. The recovery email address for this account appears to be in the name of GROSECLOSE’s significant other, with whom he has two children in common. Additionally, I have reviewed subscriber records from U.S. Cellular, related to the phone number [my redaction]. This number, along with another, are connected to an account in the name of GROSECLOSE’s significant other. The billing address for this account is [my redaction]. One of GROSECLOSE’s neighbors identified [my redaction] as GROSECLOSE’s address.

This seems to confirm that FBI obtained a geofence warrant from Google, but — at least as described — it was focused on those at the Capitol, perhaps focused on the Rotunda and anything 100 feet from it. This is the kind of granularity that will exclude most uninvolved people. They may have used it (or included it in the affidavit) because by wearing a gas mask, Groseclose made it difficult to show his face in the existing film of the attack.

The affidavit suggests that the Google geofence relied not just on GPS data of users’ phones, but also Wi-Fi access points (there’s another affidavit where the suspect’s phone triggered the Capitol Wi-Fi) and Bluetooth beacons. Again, given how wired the Capitol is, this would offer a granularity to the data that wouldn’t exist in most geofence warrants.

Finally, and most interestingly, this affidavit (obtained on the same day as the The Intercept story and so presumably after the Intercept called for comment) describes that the FBI has an “Exclusion List” of everyone who had a known legal right to be in the Capitol that day. That suggests that, after such time as the FBI completed this list, they could identify which of those present in the Capitol were probably there illegally.

There are concerns about FBI putting together a list like this. After all, Members of Congress might have good Separation of Power reasons to want to keep their personal phone numbers private. That said, there’s reason to believe that the FBI has used this method of separating out congressional identifiers and creating a white list in the past (including with the Section 215 phone dragnet), with congressional approval.

The concern arises in FBI’s definition of how it describes those legally present:

- Members of Congress

- Congressional staffers

- Law enforcement responding to the insurrection (as distinct from law enforcement joining in it)

- Secret Service Protectees (AKA, Mike Pence and his family)

- Other government employees (like custodial staff)

- Medical staff

Not on this list? Journalists, not even those journalists holding valid congressional credentials covering the vote certification.

Already, there have been several cases where suspects have claimed to be present as media, only to be charged both because of their comments while present and the fact that they don’t have congressional credentials. Three are:

- Provocateur John Sullivan, who filmed the riot and sold the footage to multiple media outlets and “claimed to be an activist and journalist that filmed protests and riots, but admitted that he did not have any press credentials.”

- Nick DeCarlo, who told the LA Times he and Nicholas Ochs were there as journalists but who FBI noted, “is not listed as a credentialed reporter with the House Periodical Press Gallery or the U.S. Senate Press Gallery, the organizations that credential Congressional correspondents.”

- Brian McCreary, who on his own sent the video he took on his phone while inside the Capitol, but who later admitted to the FBI that entering the Capitol “might not have been legal” and also described admitting to cops present that he was not a member of the media.

If the FBI is going to use official credentials to distinguish journalists from trespassers, then it could also use those credentialing lists to white list journalists present at the Capitol. But to do that, the journalists in question would have to be willing to share identifying information for all the devices that were turned on at the Capitol, something they might have good reasons not to want to do.

Plus, I suspect there are a number of journalists without Congressional credentials who were covering the events outside the Capitol and, as the rally turned into a riot, entered the Capitol to cover it. Those journalists risked their lives and provided some of the most important early information about the riot and did so in ways that in no way glorified it. But in doing so, their devices may be in an FBI database relating to the attack.

There is clear evidence that the FBI obtained location data from the Capitol as part of its investigation, including Google and almost certainly Facebook. Thus far, the available evidence suggests that the ability to target that collection narrowly limits the typical concerns about tower dumps and geofence warrants (again, any similar data collection outside the Capitol in an effort to find the person who left the pipe bombs is another issue). Moreover, almost all those legal present in the Capitol appear to be whitelisted.

But not all. And the exception, journalists, include those who have the most at stake not having their devices identified and investigated by the FBI.

All that said, perhaps a similarly controversial question pertains to preservation orders. The Intercept describes a letter from Mark Warner calling on carriers to preserve data (and rightly questioning his legal authority to make such a request), then suggests the carriers have done so on their own.

Some of the telecommunications providers questioned whether Warner has the authority to make such a request, but a number of them appear to have been preserving data from the event anyway because of the large scale of violence, the source said.

The story doesn’t consider the — by far — most likely explanation, which is that FBI served very broad preservation orders on social media companies (though some key ones, such as Facebook, would keep data for a period even after insurrectionists attempted to delete it in the days after the attack as normal practice). In any case, broad preservation orders on social media companies would be solidly within existing precedent. But I suspect it may be one of the more interesting legal questions that will come out of this investigation.

Update March 7: Added McCreary.

Pezzola

Pezzola