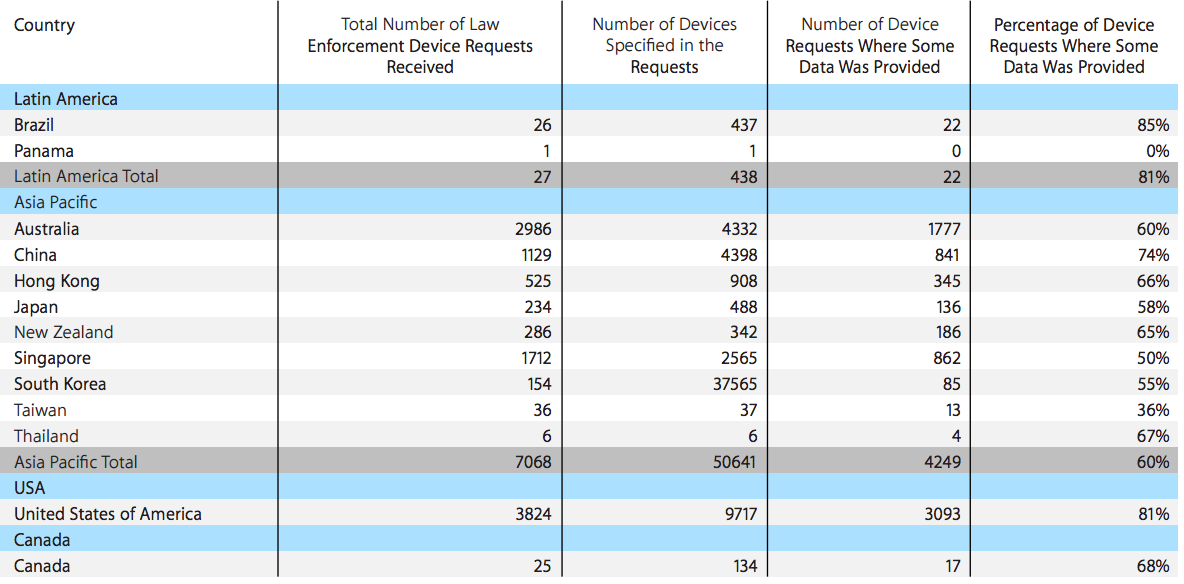

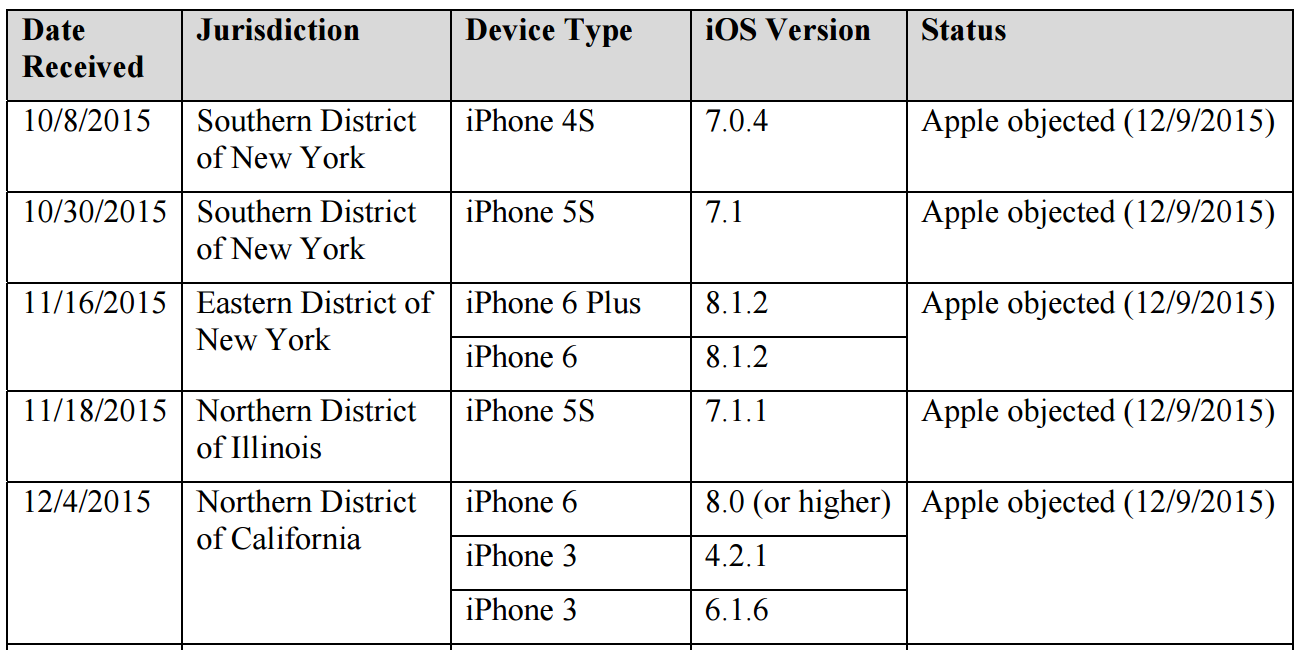

As I noted the other day, a document unsealed last week revealed that DOJ has been asking for similar such orders in other jurisdictions: two in Cincinnati, four in Chicago, two in Manhattan, one in Northern California (covering three phones), another one in Brooklyn (covering two phones), one in San Diego, and one in Boston.

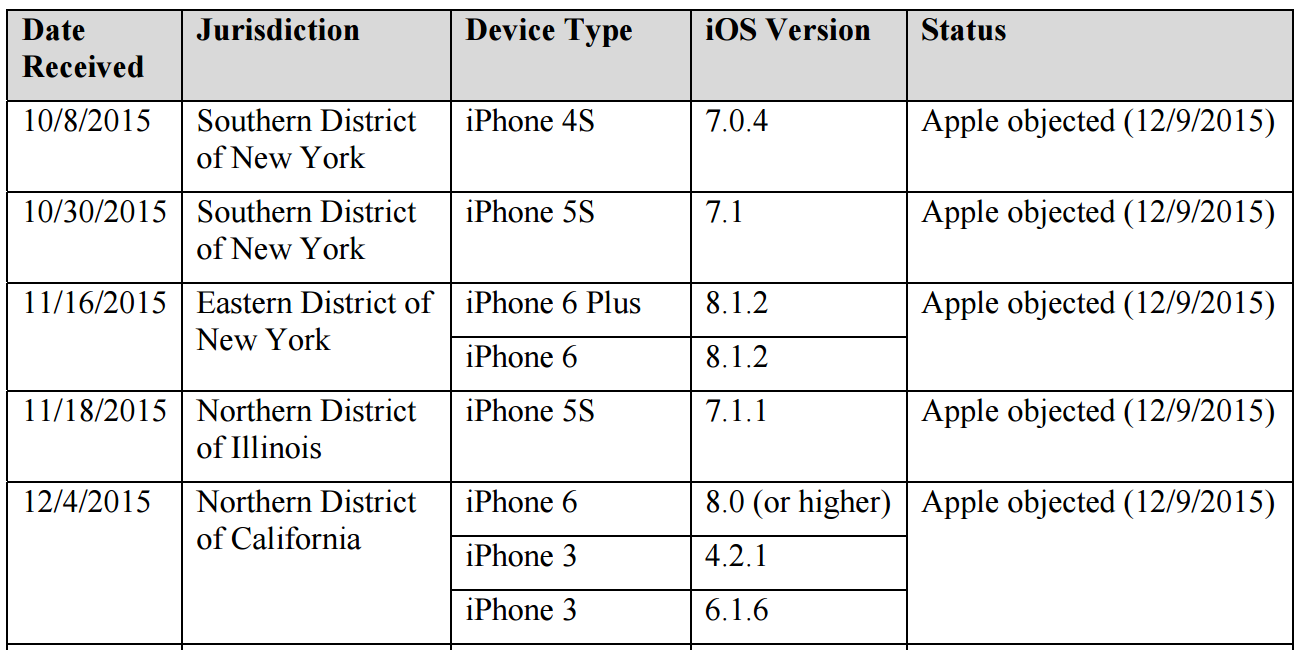

According to Apple, it objected to at least five of these orders (covering eight phones) all on the same day: December 9 (note, FBI applied for two AWAs on October 8, the day in which Comey suggested the Administration didn’t need legislation, the other one being the Brooklyn docket in which this list was produced).

The government disputes this timeline.

In its letter, Apple stated that it had “objected” to some of the orders. That is misleading. Apple did not file objections to any of the orders, seek an opportunity to be heard from the court, or otherwise seek judicial relief. The orders therefore remain in force and are not currently subject to litigation.

Whatever objection Apple made was — according to the government, anyway — made outside of the legal process.

But Apple maintains that it objected to everything already in the system on one day, December 9.

Why December 9? Why object — in whatever form they did object — all on the same day, effectively closing off cooperation under AWAs in all circumstances?

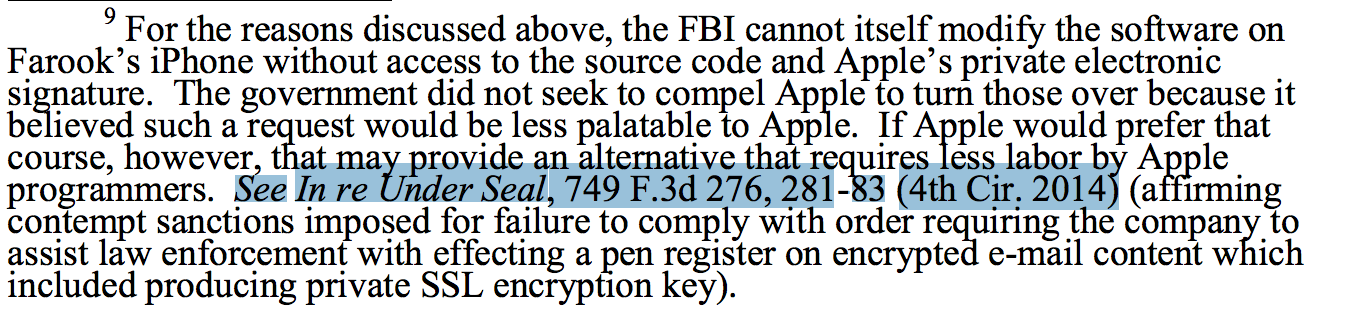

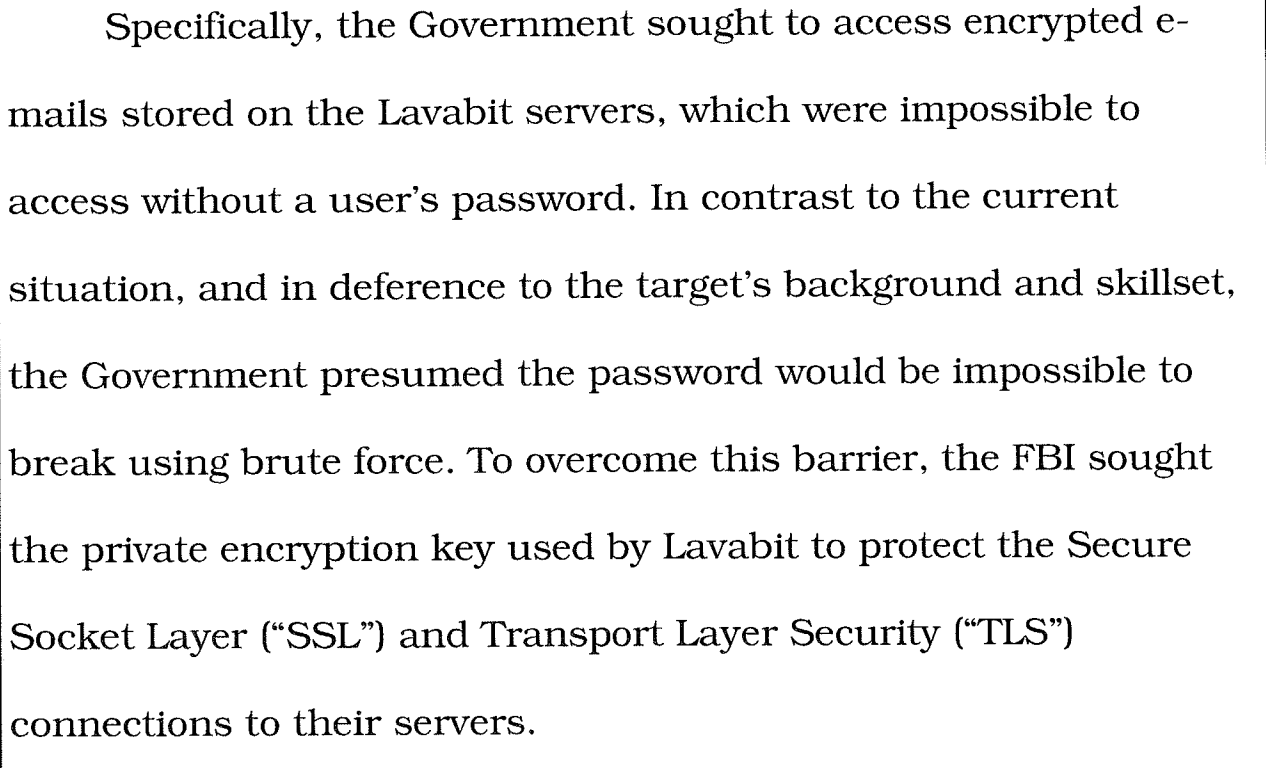

There are two possibilities I can think of, though they are both just guesses. The first is that Apple got an order, probably in an unrelated case or circumstance, in a surveillance context that raised the stakes of any cooperation on individual phones in a criminal context. I’ll review this at more length in a later post, but for now, recall that on a number of occasions, the FISA Court has taken notice of something magistrates or other Title III courts have done. For location data, FISC has adopted the standard of the highest common denominator, meaning it has adopted the warrant standard for location even though not all states or federal districts have done so. So the decisions that James Orenstein in Brooklyn and Sheri Pym in Riverside make may limit what FISC can do. It’s possible that Apple got a FISA request that raised the stakes on the magistrate requests we know about. By objecting across the board — and thereby objecting to requests pertaining to iOS 8 phones — Apple raised the odds that a magistrate ruling might help them out at FISA. And if there’s one lawyer in the country who probably knows that, it’s Apple lawyer Marc Zwillinger.

Aside the obvious reasons to wonder whether Apple got some kind of FISA request, in his interview with ABC the other day, Tim Cook described “other parts of government” asking for more and more cases (though that might refer to state and city governments asking, rather than FBI in a FISA context).

The software key — and of course, with other parts of the government asking for more and more cases and more and more cases, that software would stay living. And it would be turning the crank.

The other possibility is that by December 9, Apple had figured out that — a full day after Apple had started to help FBI access information related to the San Bernardino investigation, on December 6 — FBI took a step (changing Farook’s iCloud password) that would make it a lot harder to access the content on the phone without Apple’s help. Indeed, I’m particularly interested in what advice Apple gave the FBI in the November 16 case (involving two iOS 8 phones), given that it’s possible Apple was successfully recommending FBI pursue alternatives in that case which FBI then foreclosed in the San Bernardino case. In other words, it’s possible Apple recognized by December 9 that FBI was going to use the event of a terrorist attack to force Apple to back door its products, after which Apple started making a stronger legal stand than they might otherwise have done pursuant to secret discussions.

That action — FBI asking San Bernardino to change the password — is something Tim Cook mentioned several times in his interview with ABC the other night, at length here:

We gave significant advice to them, as a matter of fact one of the things that we suggested was “take the phone to a network that it would be familiar with, which is generally the home. Plug it in. Power it on. Leave it overnight–so that it would back-up, so that you’d have a current back-up. … You can think of it as making of making a picture of almost everything on the phone, not everything, but almost everything.

Did they do that?

Unfortunately, in the days, the early days of the investigation, an FBI–FBI directed the county to reset the iCloud password. When that is done, the phone will no longer back up to the Cloud. And so I wish they would have contacted us earlier so that that would not have been the case.

How crucial was that missed opportunity?

Assuming the cloud backup was still on — and there’s no reason to believe that it wasn’t — then it is very crucial.

And it’s something they harped on in their motion yesterday.

Unfortunately, the FBI, without consulting Apple or reviewing its public guidance regarding iOS, changed the iCloud password associated with one of the attacker’s accounts, foreclosing the possibility of the phone initiating an automatic iCloud back-up of its data to a known Wi-Fi network, see Hanna Decl. Ex. X [Apple Inc., iCloud: Back up your iOS device to iCloud], which could have obviated the need to unlock the phone and thus for the extraordinary order the government now seeks.21 Had the FBI consulted Apple first, this litigation may not have been necessary.

Plus, consider the oddness around this iCloud information. FBI would have gotten the most recent backup (dating to October 19) directly off Farook’s iCloud account on December 6.

But 47 days later, on January 22, they obtained a warrant for that same information. While they might get earlier backups, they would have received substantially the same information they had accessed directly back in December, all as they were prepping going after Apple to back door their product. It’s not clear why they would do this, especially since there’s little likelihood of this information being submitted at trial (and therefore requiring a parallel constructed certified Apple copy for evidentiary purposes).

There’s one last detail of note. Cook also suggested in that interview that things would have worked out differently — Apple might not have made the big principled stand they are making — if FBI had never gone public.

I can’t talk about the tactics of the FBI, they’ve chosen to do what they’ve done, they’ve chosen to do this out in public, for whatever reasons that they have.What we think at this point, given it is out in the public, is that we need to stand tall and stand tall on principle. Our job is to protect our customers.

Again, that suggests they might have taken a different tack with all the other AWA orders if they only could have done it quietly (which also suggests FBI is taking this approach to make it easier for other jurisdictions to get Apple content). But why would they have decided on December 9 that this thing was going to go public?

Update: This language, from the Motion to Compel, may explain why they both accessed the iCloud and obtained a warrant.

The FBI has been able to obtain several iCloud backups for the SUBJECT DEVICE, and executed a warrant to obtain all saved iCloud data associated with the SUBJECT DEVICE. Evidence in the iCloud account indicates that Farook was in communication with victims who were later killed during the shootings perpetrated by Farook on December 2, 2015, and toll records show that Farook communicated with Malik using the SUBJECT DEVICE. (17)

This passage suggests it obtained both “iCloud backups” and “all saved iCloud data,” which are actually the same thing (but would describe the two different ways the FBI obtained this information). Then, without noting a source, it says that “evidence in the iCloud account” shows Farook was communicating with his victims and “toll records” show he communicated with Malik. Remember too that the FBI got subscriber information from a bunch of accounts using (vaguely defined) “legal process,” which could include things like USA Freedom Act.

The “evidence in the iCloud account” would presumably be iMessages or Facetime. But the “toll records” could be too, given that Apple would have those (and could have turned them over in the earlier “legal process” step. That is, FBI may have done this to obscure what it can get at each stage (and, possibly, what kinds of other “legal process” it now serves on Apple).

October 8: Comey testifies that the government is not seeking legislation; FBI submits requests for two All Writs Act, one in Brooklyn, one in Manhattan; in former case, Magistrate Judge James Orenstein invites Apple response

October 30: FBI obtains another AWA in Manhattan

November 16: FBI obtains another AWA in Brooklyn pertaining to two phones, but running iOS 8.

November 18: FBI obtains AWA in Chicago

December 2: Syed Rezwan Farook and his wife killed 14 of Farook’s colleagues at holiday party

December 3: FBI seizes Farook’s iPhone from Lexus sitting in their garage

December 4: FBI obtains AWA in Northern California covering 3 phones, one running iOS 8 or higher

December 5, 2:46 AM: FBI first asks Apple for help, beginning period during which Apple provided 24/7 assistance to investigation from 3 staffers; FBI initially submits “legal process” for information regarding customer or subscriber name for three names and nine specific accounts; Apple responds same day

December 6: FBI works with San Bernardino county to reset iCloud password for Farook’s account; FBI submits warrant to Apple for account information, emails, and messages pertaining to three accounts; Apple responds same day

December 9: Apple “objects” to the pending AWA orders

December 10: Intelligence Community briefs Intelligence Committee members and does not affirmatively indicate any encryption is thwarting investigation

December 16: FBI submits “legal process” for customer or subscriber information regarding one name and seven specific accounts; Apple responds same day

January 22: FBI submits warrant for iCloud data pertaining to Farook’s work phone

January 29: FBI obtains extension on warrant for content for phone

February 14: US Attorney contacts Stephen Larson asking him to file brief representing victims in support of AWA request

February 16: After first alerting the press it will happen, FBI obtains AWA for Farook’s phone and only then informs Apple

![[image (mod): LeAnn E. Crowe via Flickr]](https://www.emptywheel.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/FlintWaterCrisis_logo-201x300.jpg)