The Ugly Results Of Inequality

Posts in this series. This post is updated from time to time with additional resources.

In the last two posts in this series I looked at the the way unequal freedom and hierarchies of social relationships play out in the US. In this post I address two ugly consequences of those inequalities.

Anger and Hostility

Most people have a good idea of where they are in the social hierarchies described by Elizabeth Anderson in her paper Equality, those I discussed in previous posts in this series. They know who dominates them, who holds them in high or low esteem, and whether their opinions about their best interests influence decisions affecting them. They live their lives in these webs of influence and social relations, and they respond emotionally and practically.

I don’t think people have very clear ideas about freedom. Everyone understands negative freedom, because they constantly confront it. But I doubt people think about their positive freedom, the range of opportunities they can reasonably enjoy. If they do, they certainly don’t think they have any chance of changing that range. [1]

Freedom from domination is even less well understood. For people of color and most poor white people, domination is normal. That isn’t so obvious to most non-poor white people. I don’t know, but I’d guess working people don’t think of their employer as dominating them. I’d guess most people think this is perfectly normal, the natural operation of the job market. This is the view Anderson attacks in her book Private Government.

As we learned from Pierre Bourdieu, the dominant class arranges things so that both the dominant and the subservient classes think everything is normal, that one class should dominate and the rest should be subservient, and that everything is just fine. But today it’s hard to sustain that illusion.

The public at large is fully aware of their lack of freedoms available only to the dominant class. Too many of us are faced with the limitations imposed by the negative freedom of others, dominated, and lacking in realistic opportunities for human flourishing. People know they are low in all social hierarchies, they feel it in their bones. They are aware that the dominant class holds them in contempt, and controls their lives. This breeds anger and hostility.

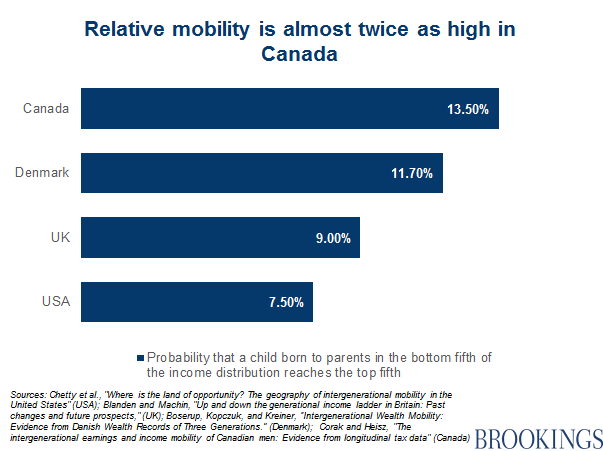

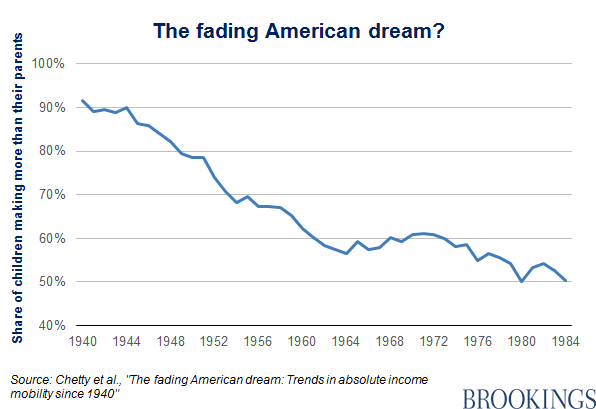

Unequal distribution of material goods

The interests of the dominant class have controlled our political discourse, but the level of control has increased dramatically during the last 50 years. The result is historically high inequality in material wealth. In my view, the ultimate cause is neoliberal ideology, which is supported by both political parties. It drives the government to abandon the interests of the majority in favor of unregulated capitalism. [2] I think that underlying the neoliberal ideology is an economic theory, neoclassical economics, which is based on the hypothesis of marginal utility, which in turn is based on utilitarianism. [3]

One good example of the way utilitarianism creates norms is set out in this post. The theory of marginal utility is used to show that wages, rents, and returns to capital are balanced in accordance with a natural law, and everything works out justly. In the real world, this is nonsense, but lots of people believe it even today. The post also shows that other outcomes are possible.

In the real world, it’s a simple fact: the rich arrange the rules of the economy to benefit themselves at the expense of the lives, health and income of the rest of us. See, e.g., this detailed discussion of the manipulation of the “market” by the insulin cartel.

A Toxic Combination

As these inequalities increased and became apparent to the least observant after the Great Crash, the dominant class refused to allow any changes to the system that made them rich. Instead, they and their allies became even more vociferous in deflecting the blame from the dominant class to groups of people in the subservient class, immigrants, the poor, people of color, academics, activists, the left, scientists, liberals, and professionals. Their demagogues have inflamed a large group of people. History teaches us that there is always a substantial group that can be counted on to respond to that kind of rhetoric with anger, fear, and occasionally violence. [4]

The claim that they are responsible for the problems facing society seems preposterous to the targeted groups, especially academics, scientists and liberals. They see themselves as supporting a good society, one in which there is more freedom and equality. None of the targeted groups have a good way to engage with what they see as idiocy. Their responses seem patronizing, or defensive, or angry, or morally unmoored.

Right-wing authoritarian demagoguery cannot be tamed by counter-rhetoric or by PR fixes. It appeals to something deeper than rational argument. I hope it can be effectively countered by appeals to morals and values, coupled with actions to show that things can be better. I believe that the values Anderson discusses and the morality they represent are the basis for that battle.

=====

[1] For a general look at this, see my discussion of Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus. See also Jennifer Silva’s book Coming Up Short. This paper by Silva and Sarah Corse investigates factors that explain how some working class young people are able to drive themselves through to college.

[2] I arrived at this conclusion after a long course of reading and writing. You can find it on my author page, which is linked to my name above. For a summary, see this post.

[3] I give a brief description under the subhead Modern Monetary Theory here. You can find more by searching on Jevons at this site.

[4] See, for example, The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt, especially the discussion of anti-Semitism. See also Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation. I discuss these books at length in earlier series, indexed here and here.