FBI Is Not “Surveilling” WikiLeaks Supporters in Its Never-Ending Investigation; Is It “Collecting” on Them?

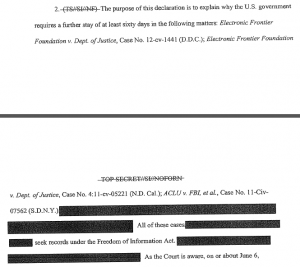

The FOIA for records on FBI’s surveillance of WikiLeaks supporters substantially ended yesterday (barring an appeal) when Judge Barbara Rothstein ruled against EPIC. While she did order National Security Division to do a more thorough search for records, she basically said the agencies had properly withheld records under Exemption 7(A) for its “multi-subject investigation into the unauthorized disclosure of classified information published on WikiLeaks, which is ‘still active and ongoing’ and remains in the investigative stage.” (Note, the claim that the investigation is still in what FBI calls an investigative stage, which I don’t doubt, is nevertheless dated, as the most recent secret declarations in this case appear to have been submitted on April 25, 2014, though Rothstein may not have read them until after she approved such ex parte submissions on July 29 of last year.)

In so ruling, Rothstein has dodged a key earlier issue, which is that all three entities EPIC FOIAed (DOJ’s Criminal and National Security Division and FBI) invoked a statutory Exemption 3 from FOIA, but refused to explain what statute they were using.

2 Defendants also rely on Exemptions 1, 3, 5, 6, 7(C), 7(D), 7(E), and 7(F). The Court, finding that Exemption 7(A) applies, does not discuss whether these alternative exemptions may apply.

I have argued — and still strongly suspect — that the government was relying, in part, on Section 215 of PATRIOT, as laid out in this post.

In addition to the Exemption 3 issue Rothstein dodged, though, there were three other issues that were of interest in this case.

First, we’ve learned in the 4 years since EPIC filed this FOIA that their request falls in the cracks of the language the government uses about its own surveillance (which it calls intelligence, not surveillance). EPIC asked for:

- All records regarding any individuals targeted for surveillance for support for or interest in WikiLeaks;

- All records regarding lists of names of individuals who have demonstrated support for or interest in WikiLeaks;

- All records of any agency communications with Internet and social media companies including, but not limited to Facebook and Google, regarding lists of individuals who have demonstrated, through advocacy or other means, support for or interest in WikiLeaks; and

- All records of any agency communications with financial services companies including, but not limited to Visa, MasterCard, and PayPal, regarding lists of individuals who have demonstrated, through monetary donations or other means, support or interest in WikiLeaks. [my emphasis]

As I’ve pointed out in the past, if the FBI obtained datasets rather than lists of the people who supported WikiLeaks from Facebook, Google, Visa, MasterCard, and PayPal, FBI would be expected to deny it had lists of such supporters, as it has done. We’ve since learned about the extent to which it does collect datasets when carrying out intelligence investigations.

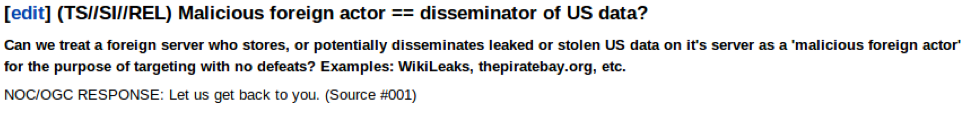

Then there’s our heightened understanding of the words “target” and “surveillance” which are central to request 1. The US doesn’t target a lot of Americans, but it does collect on them. And when it does so — even if it makes queries that return their identifiers — it doesn’t consider that “surveillance.” That is, the FBI would only admit to having responsive data to request 1 if it were obtaining FISA or Title III warrants against mere supporters of WikiLeaks, rather than — say — reading their email to Julian Assange, whom FBI surely has targeted and still targets under Section 702 and other surveillance authorities, or even, as I guarantee you has happened, looked up people after the fact and discovered they had previous conversations with Assange. We’ve even learned that NSA collects vast amounts of Internet communications that talk “about” a targeted person’s selector, meaning that Americans’ communications might be pulled if they used WikiLeaks or Assange’s Internet identifiers in the body of their emails or chats. None of that would count as “targeted” “surveillance,” but it is presumably among the kinds of things EPIC had in mind when it tried to learn how FBI’s investigation of WikiLeakas was implicating completely innocent supporters.

I noted the way FBI’s declaration skirted both these issues some years ago, and everything we’ve learned since only raises the likelihood that FBI is playing a narrow word game to claim that it doesn’t have any responsive records, but out of an act of generosity it nevertheless considered the volumes of FBI records that are related to the request that it nevertheless has declared 7(A) over. Rothstein’s order replicates the use of the word “targeting” to discuss FBI’s search, suggesting the distinction is as important as I suspect.

Plaintiff first argues that the release of records concerning individuals who are simply supporting WikiLeaks could not interfere with any pending or reasonably anticipated enforcement proceeding since their activity is legal and protected by the First Amendment. Pl.’s Cross-Mot. at 14. This argument is again premised on Plaintiff’s speculation that the Government’s investigation is targeting innocent WikiLeaks supporters, and, for the reasons previously discussed, the Court finds it lacks merit.

All of which brings me to the remaining interesting subtext of this ruling.

Five years after the investigation into WikiLeaks must have started in earnest, 20 months after Chelsea Manning was found guilty for leaking the bulk of the documents in question, and over 10 months since Rothstein’s most recent update on the “investigation” in question, Rothstein is convinced these records may adequately be withheld because there is an active investigation.

While it’s possible DOJ is newly considering charges related to other activities of WikiLeaks — perhaps charges relating to WikiLeaks’ assistance to Edward Snowden in escaping from Hong Kong, though like Manning’s verdict, that was over 20 months ago — it’s also very likely the better part of whatever ongoing investigation into WikiLeaks is ongoing is an intelligence investigation, not a criminal one. (See this post for my analysis of the language they used last year to describe the investigation.)

Rothstein is explicit that DOJ still has — or had, way back when she read fresh declarations in the case — a criminal investigation, not just an intelligence investigation (which might suggest Assange’s asylum in the Ecuador Embassy in London is holding up something criminal).

In stark contrast to the CREW panel, this Court is persuaded that there is an ongoing criminal investigation. Unlike the vague characterization of the investigation in CREW, Defendants have provided sufficient specificity as to the status of the investigation, and sufficient explanation as to why the investigation is of long-term duration. See e.g., Hardy 4th Decl. ¶¶ 7, 8; Bradley 2d Decl. ¶ 12; 2d Cunningham Decl. ¶ 8.

Yet much of her language (which, with one exception, relies on the earliest declarations submitted in this litigation) sounds like that reflecting intelligence techniques as much as criminal tactics.

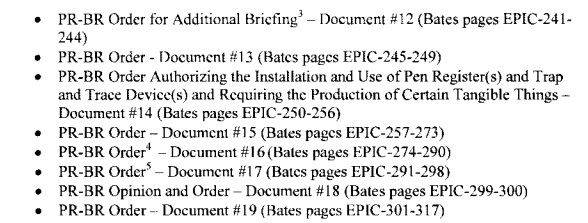

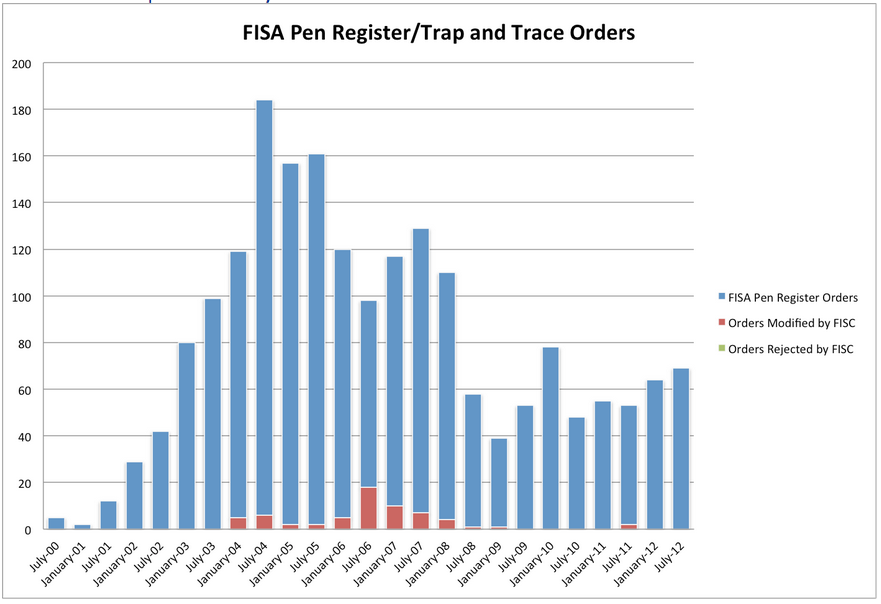

Here, the FBI and CRM have determined that the release of information on the techniques and procedures employed in their WikiLeaks investigation would allow targets of the investigation to evade law enforcement, and have filed detailed affidavits in support thereof. Hardy 1st Decl. ¶ 25; Cunningham 1st Decl. ¶ 11. As Plaintiff notes, certain court documents related to the Twitter litigation have been made public and describe the agencies’ investigative techniques against specific individuals. To the extent that Plaintiff seeks those already-made public documents, the Court is persuaded that their release will not interfere with a law enforcement proceeding and orders that Defendants turn those documents over.

[snip]

In the instant case, releasing all of the records with investigatory techniques similar to that involved in the Twitter litigation may, for instance, reveal information regarding the scope of this ongoing multi-subject investigation. This is precisely the type of information that Exemption 7(A) protects and why this Court must defer to the agencies’ expertise.

I’m left with the impression that FBI has reams of documents responsive to what EPIC was presumably interested in — how innocent people have had their privacy compromised because they support a publisher the US doesn’t like — but that they’re using a variety of tired dodges to hide those documents.