Update: See this post, which explains that I’m wrong about the timing of Verizon’s different approach to production than AT&T. And that difference precedes Verizon’s withdrawal from the FBI call record program in 2009 — it goes back to 2007.

I’m finally getting around to listening to the Klayman v. Obama hearing from the other day, which you can listen to here. I’ll have more to say on it later. But my impression is that — because of the incomplete reporting of a bunch of NSA beat reporters — Klayman may be improperly thrown out on standing because he is only a Verizon cell customer, not a Verizon landline customer.

Back on June 14, 2013, the WSJ reported that Verizon Wireless and T-Mobile don’t turn over records under the phone dragnet, but that the government obtains those records anyway as they travel across the domestic backbone, largely owned by AT&T and Verizon Business Services.

The National Security Agency’s controversial data program, which seeks to stockpile records on all calls made in the U.S., doesn’t collect information directly from T-Mobile USA and Verizon Wireless, in part because of their foreign ownership ties, people familiar with the matter said.

The blind spot for U.S. intelligence is relatively small, according to a U.S. official. Officials believe they can still capture information, or metadata, on 99% of U.S. phone traffic because nearly all calls eventually travel over networks owned by U.S. companies that work with the NSA.

[snip]

Much of the U.S.’s telecom backbone is owned by two companies: AT&T and Verizon Business Network Services Inc., a U.S. subsidiary of Verizon Communications that it views as a separate network from its mobile business. It was the Verizon subsidiary that was named in the FISA warrant leaked by NSA contractor Edward Snowden to the Guardian newspaper and revealed last week.

When a T-Mobile or Verizon Wireless call is made, it often must travel over one of these networks, requiring the carrier to pay the cable owner. The information related to that transaction—such as the phone numbers involved and length of call—is recorded and can then be passed to the NSA through its existing relationships.

Then, on February 7, 2014, the WSJ (and 3 other outlets) reported something entirely different — that the phone dragnet only collects around 20% of phone records (others reported the number to be a higher amount).

The National Security Agency’s collection of phone data, at the center of the controversy over U.S. surveillance operations, gathers information from about 20% or less of all U.S. calls—much less than previously thought, according to people familiar with the NSA program.

The program had been described as collecting records on almost every phone call placed in the U.S. But, in fact, it doesn’t collect records for most cellphones, the fastest-growing sector in telephony and an area where the agency has struggled to keep pace, the people said.

Over the course of 8 months, the WSJ’s own claim went from the government collecting 99% of phone data (defined as telephony) to the government collecting 20% (probably defining “call data” broadly to include VOIP), without offering an explanation of what changed. And it was not just its own earlier reporting with which WSJ conflicted; aspects of it also conflicted with a lot of publicly released primary documents about what the program has done in the past. Nevertheless, there was remarkably little interest in explaining the discrepancy.

I’m getting a lot closer to being able to explain the discrepancy in WSJ’s reporting. And if I’m right, then Larry Klayman should have standing (though I’m less certain about Anna Smith, who is appealing a suit in the 9th Circuit).

I’m fairly certain (let me caveat: I think this is the underlying dynamic; the question is the timing) the discrepancy arises from the fact that, for the first time ever, on July 19, 2013 (a month after the WSJ’s first report) the FISA Court explicitly prohibited the collection of Cell Site Location Information.

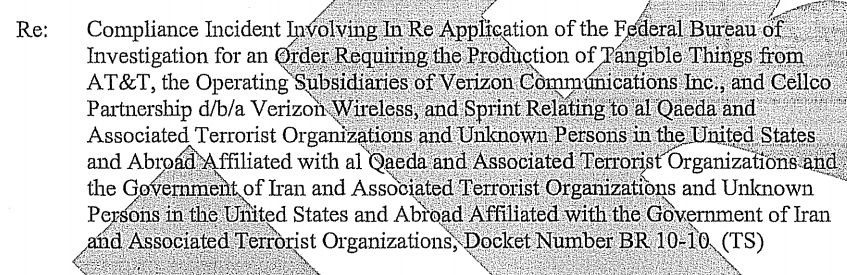

Furthermore, this Order does not authorize the production of cell site location information (CSLI).

We’ve learned several details since February that puts this in context.

First, the NSL IG Report revealed that one of the three providers who had been part of FBI’s onsite call records access from 2003 to 2006 did not renew the contract for that program in 2009.

Company A, Company B, and Company C are the three telephone carriers described in our Exigent Letters Report that provided telephone records to the TCAU in response to exigent letters and other informal requests between 2003 and 2006. As described in our Exigent Letters Report, the FBI entered into contracts with these carriers in 2003 and 2004, which required that the communication service providers place their employees in the TCAU’s office space and give these employees access to their companies’ databases so they could immediately service FBI requests for telephone records. Exigent Letters Report, 20. As described in the next chapter, TCAU no longer shares office space with the telephone providers. Companies A and C continue to serve FBI requests for telephone records and provide the records electronically to the TCAU. Company B did not renew its contract with the FBI in 2009 and is no longer providing telephone records directly to the TCAU. Company B continues to provide telephone records in response to NSL requests issued directly by the field without TCAU’s assistance.

The original WSJ, in retrospect, makes it fairly clear that Company B is Verizon (though I believe it provides the wrong explanation otherwise for Verizon’s inability to provide records, that it was partly foreign owned–though admittedly it only claims to be providing part of the explanation).

Unlike Sprint and AT&T, [Verizon Wireless and T-Mobile] also don’t perform classified work for the government. Such contracts require secure facilities that make cooperating with NSA programs simpler, people familiar with the matter said.

Verizon Associate General Counsel Michael Woods’ response to questions at a hearing earlier this year made it even more clear. He said that Verizon does not keep call detail records — as distinct from billing records — long at all (and they only keep billing records on the landline side for 18 months).

The contract with TCAU, the NSL IG Report (and the earlier Exigent Letters report) makes clear, would require providers to keep records for longer to facilitate some bells and whistles. That’s a big part of what the “make cooperating with NSA programs simpler” is likely about. Therefore, Verizon must be the provider that stopped retaining records in 2009 for the purpose of the government (It also just so happens to be the provider that doesn’t need the government cash as part of its business model). I suspect that TCAU remains closely related to Hemisphere, which may be why when I asked FBI about its participation in that unclassified project, FBI refused to comment at all.

If all that’s right, then AT&T and Sprint retain their call detail records because they have signed a contract with the government to do so. Verizon does not.

That means, at least since 2009, Verizon has been relying on actual call detail records to fulfill its obligations under Section 215, not a database that makes it easier to pull out precisely what the government wants (indeed, I suspect the end of the contract created the problems where Verizon was providing entirely foreign calls along with its domestic calls starting with the May 29, 2009 order). The business records that Verizon had on hand was a CDR that, in the case of cell phones, necessarily included CSLI.

Verizon is still (the Verizon-specific language remains in the dragnet orders, and they challenged the first order after Leon’s decision in this case) providing records of landline calls that traverse its backbone.

But when FISC made it a violation — rather than just overproduction they otherwise would have and have, in both this and other programs, approved — to provide CSLI, and made that public, it gave Verizon the opportunity to say it had no way to provide the cell data legally.

That’s sort of what the later WSJ report says, though it doesn’t explain why this would be limited in time or why NSA would have a problem when it collects CDRs internationally with CSLI with no problem.

Moreover, the NSA has been stymied by how to remove location data—which it isn’t allowed to collect without getting additional court approval—from U.S. cellphone records collected in bulk, a U.S. official said.

I’m not sure whether it’s the case that Verizon couldn’t very easily pull that CSLI off or not. But I do suspect — particularly for a program that offers no compensation — that Verizon no longer had a legal obligation to. (This probably answers, by the way, how AT&T and Sprint are getting paid here: they’re being paid to keep their CDRs under the old TCAU contracts with the FBI.)

The government repeats over and over that they’re only getting business records the companies already have. Verizon has made it clear it doesn’t have cell call detail records without the location attached. And therefore, I suspect, the government lost its ability to make Verizon comply. That is also why, I suspect, the President claims he needs new legislation to make this happen: because he needs language forcing the providers to provide the CDRs in the form the government wants it in.

If I’m right, though — that the government had 99% coverage of telephony until Claire Eagan specifically excluded cell location — then Klayman should have standing. That’s because Richard Leon’s injunction not only prohibited the government from collecting any new records from Klayman, he also required the government to “destroy any such metadata in its possession that was collected through the bulk collection program.”

Assuming Verizon just stopped providing cell data in 2013 pursuant to Eagan’s order, then there would still be over 3 years of call records in the government’s possession available for search. Which would mean he would still be exposed to the government’s improper querying of his records.

It is certainly possible that Verizon stopped providing cell data once it ended its TCAU contact in 2009. If that’s the case, the government’s hasty destruction of call records in March would probably have eliminated the last of the data it had on Klayman (though not on ACLU, since ACLU is a landline customer as well as a wireless customer).

But if Verizon just stopped handing over cell records in 2013 after Claire Eagan made it impossible for the government to force Verizon to comply with such orders, then Klayman — and everyone else whose records transited Verizon’s backbone — should still have standing.

Update: I provided this further explanation to someone via email.

I should have said this more clearly in the post. But the only way everyone is correct: including WSJ in June, Claire Eagan’s invocation of “substantially all” in July, the PRG’s claims they weren’t getting as much as thought in December, and WSJ’s claims they weren’t much at all in February, is if Verizon shut down cell collection sometime during that period. The July order and the aftermath would explain that.

I suspect the number is now closer to 50-60% of US based telephony records within the US (remember, on almost all international traffic, there should be near duplication, because they’re collecting that at scale offshore), but there’s also VOIP and other forms of “calls” and texts that they’re not getting, which is how you get down to the intentionally alarmist 20%. One reason I think Comey’s going after Apple is because iMessage is being carved out, and Verizon is already pissed, so he needs to find a way to ensure that Apple doesn’t get a competitive advantage over Verizon by going through WiFi that may not be available to Verizon because it is itself the backbone. But if you lose both Verizon’s cell traffic AND any cell traffic they carry, you lose a ton of traffic.

That gets you to the import of the FBI contract. It is a current business purpose of AT&T and Sprint to create a database that they can charge the FBI to use to do additional searching, including location data and burner phones and the like. AT&T’s version of this is probably Hemisphere right now (thus, in FBI-speak, TCAU would be Hemisphere), meaning they also get DEA and other agencies to pay for it. In that business purpose, the FBI is a customer of AT&T and Sprint’s business decision to create its own version of the NSA’s database, including all its calls as well as things like location data the FBI can get so on individualized basis.

Verizon used to choose to pursue this business (this is the significance, I think, of the government partially relying on a claim to voluntary production, per Kris). In 2009, they changed their business approach and stopped doing that. So they no longer have a business need to create and keep a database of all its phone records.

What they do still have are

SS7 routing records of all traffic on their backbone, which they need to route calls through their networks (which is what AT&T uses to build their database). That’s the business record they use to respond to their daily obligations.

But there seem to be two likely reasons why the FISC can’t force Verizon to alter those SS7 records, stripping the CSLI before delivering it to the government. First, there is no means to compensate the providers under Section 215. That clearly indicates Congress had no plan to ask providers to provide all their records on a daily basis. But without compensation, you can’t ask the providers to do a lot of tweaking.

The other problem is if you’re asking the providers to create a record, then you’re getting away from the Third Party doctrine, aren’t you? In any case, the government and judges have repeated over and over, they can only get existing business records the providers already have. Asking Verizon to do a bunch to tweak those records turns it into a database that Verizon has created not for its own business purpose, but to fulfill the government’s spying demands.

I think this is the underlying point of Woods’ testimony where he made it clear Verizon had no intent of playing Intelligence agent for the government. Verizon seems to have made it very clear they will challenge any order to go back into the spying for the government business (all the more so after losing some German business because of too-close ties to the USG). And since Verizon is presumably now doing this for relatively free (since 2009, as opposed to AT&T and Sprint, who are still getting paid via their FBI contract), the government has far less ability to make demands.

This is also where I think the cost from getting complete coverage comes from. You have to pay provider sufficiently such that they are really doing the database-keeping voluntarily, which presumably gets it well beyond reasonable cost compensation.

Update: One final point (and it’s a point William Ockham made a billion years ago). The foreign data problem Verizon had starting in 2009 would be completely consistent with a shift from database production to SS7 production, because SS7 records are going to have everything that transits the circuit.