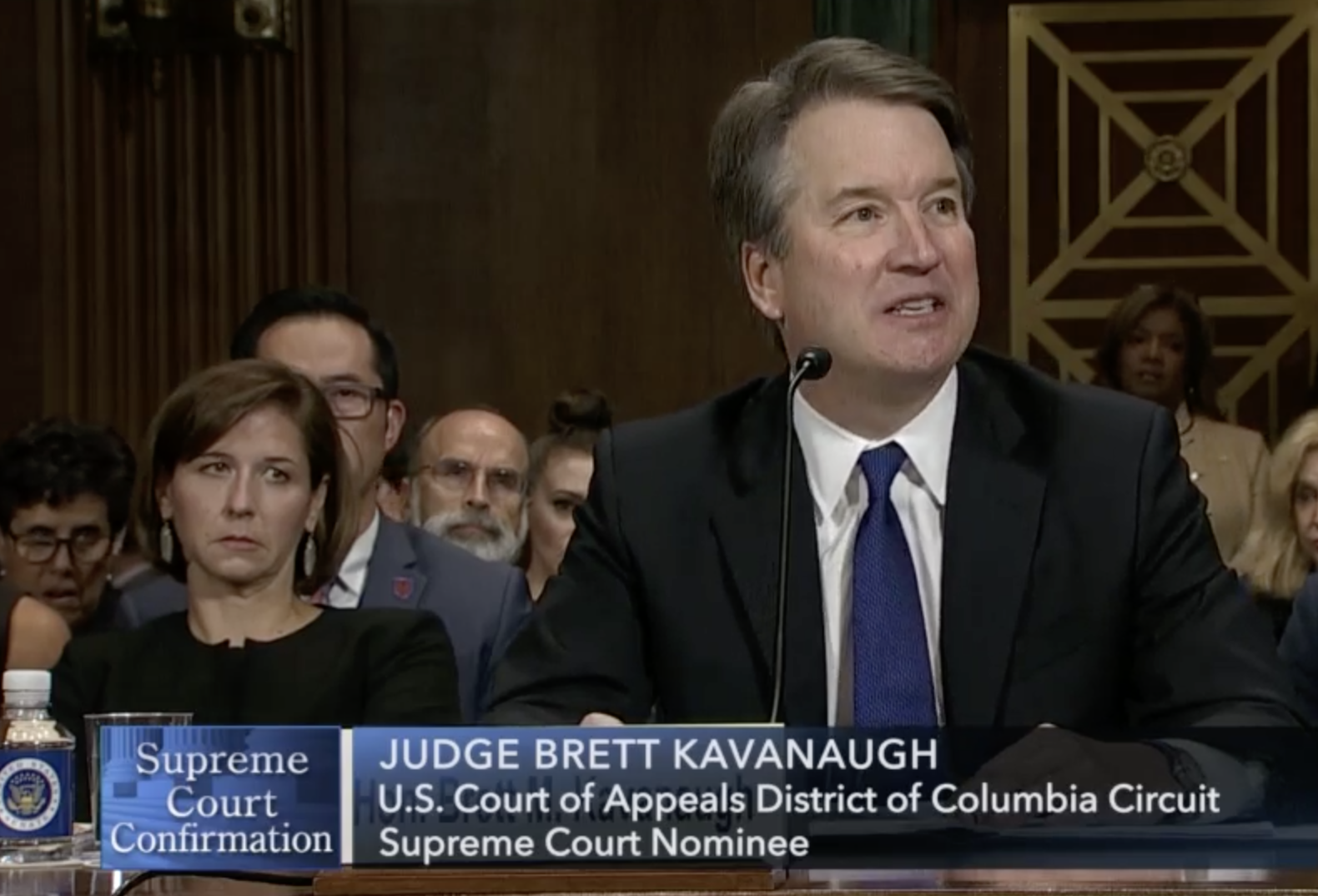

On Squi and the 65-Lady Letter

This is an insight I owe entirely to a reader, BI.

There should be an explanation for why Christine Blasey Ford was (presumably) not invited to be on the 65-lady letter backing Brett Kavanaugh pulled together just as allegations of sexual assault became public.

In spite of the fact that it got entered into the record multiple times in Thursday’s hearing, it already had diminishing value as a measure of Kavanaugh’s character. After Ford’s identity was made public, some of the women who signed the letter grew reluctant to stand by their support publicly.

Five of the women who signed the letter declined to comment when reached by POLITICO following the public revelation of Ford’s identity.

Dozens of others either didn’t respond to POLITICO’s inquiries or could not be reached.

The AP reported that “more than a dozen” stood by the letter after Ford came forward, which is not 65.

More strikingly, one of the signers of the letter, Renate Schroeder Dolphin, upon realizing that she was mocked in the yearbooks of 14 boys, including Kavanaugh, spoke instead about how hurtful his circle of friends was.

This month, Renate Schroeder Dolphin joined 64 other women who, saying they knew Judge Kavanaugh during their high school years, signed a letter to the leaders of the Senate Judiciary Committee, which is weighing Judge Kavanaugh’s nomination. The letter stated that “he has behaved honorably and treated women with respect.”

When Ms. Dolphin signed the Sept. 14 letter, she wasn’t aware of the “Renate” yearbook references on the pages of Judge Kavanaugh and his football teammates.

“I learned about these yearbook pages only a few days ago,” Ms. Dolphin said in a statement to The New York Times. “I don’t know what ‘Renate Alumnus’ actually means. I can’t begin to comprehend what goes through the minds of 17-year-old boys who write such things, but the insinuation is horrible, hurtful and simply untrue. I pray their daughters are never treated this way. I will have no further comment.”

So the letter should not, now, be treated as a validating document.

That said, if Ford was not invited to be on the letter, then it is itself proof that the letter does not reflect the views of all the women who were spending time with Kavanaugh during the summer in question.

Having spoken to some folks who were in these circles at the time, I’m not at all suspicious of the explanation behind how the letter came together immediately after Ford’s allegations — but not her identity — were made public.

It started as a series of phone calls among old high-school friends and ended up embroiling 65 women in the firestorm over a sexual assault allegation that could shape the Supreme Court.

In a matter of hours, they all signed onto a letter rallying behind high court nominee and their high school friend Brett Kavanaugh as someone who “has always treated women with decency and respect.”

I don’t regularly use Facebook. I’m not even in close contact with friends from college (who remain a tight-knit network), much less either of my high schools. But for those who do remain close with friends from their youth, especially on Facebook, such a feat would be easy to do. The network that remains close would easily come up with 65 signers. (For what it’s worth, the one network from my youth where I could be relied on to pipe up this quickly includes at least two men I know raped women in the women in the network.)

But Ford presumably wasn’t invited to be on the letter.

There are several possible explanations why she wouldn’t be, but both discredit the letter itself.

The most plausible is that she simply doesn’t run in those circles anymore. She lives on the west coast, she suffered a trauma associated with this network, she found socializing generally more difficult in the years immediately after the assault, which would have been precisely the period when she might keep up those ties.

That’s all well and good, except testimony in Thursday’s hearing makes clear that — regardless of what happened between Kavanaugh and Ford — she is one of the women who might have insight on his behavior at the time. That’s because both Kavanaugh and Ford each spent a lot of time, individually and (at least according to Ford) together that summer with the guy Ed Whelan falsely accused of the assault, whom I’ll refer to only as Squi.

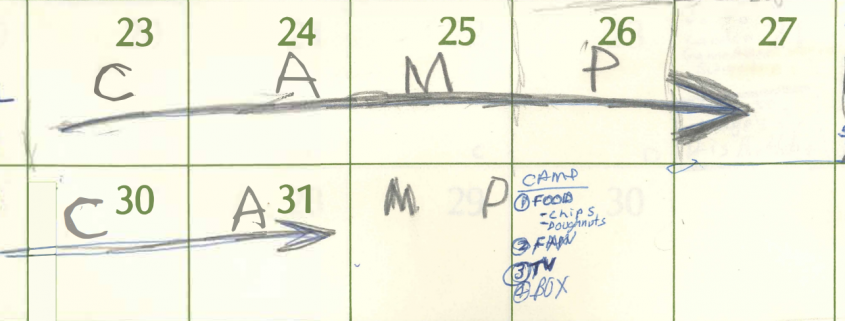

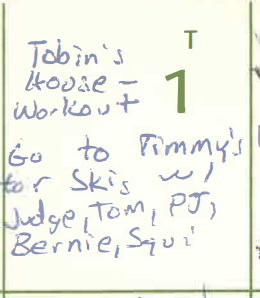

On 13 occasions, Kavanaugh refers to someone named “Squi” on his calendar. It’s the name that crops up the most. Kavanaugh and Squi, who played on the Georgetown Prep football team with him, went to a Washington Bullets game, to Squi’s house in Rehoboth, to see movies, to the beach. On July 1, Kavanaugh, Judge, PJ, Squi and two others go to “Timmy’s for skis” — an apparent reference to going to a friend’s house for beers (“brewskis”).

[snip]

Ford explained. The shared connection to Kavanaugh was the person who Whelan suggested might be the real culprit.

“How long did you know this person?” Mitchell asked.

“Maybe for— a couple of months we socialized,” Ford replied. “But he also was a member of the same country club, and I knew his younger brother as well.” That was a couple of months prior to the alleged attack, Mitchell clarified.

Mitchell then asked Ford to explain the nature of her relationship with that person.

“He was somebody that, I will use the phrase ‘I went out with,’ ” Ford said, using air quotes. “I wouldn’t say ‘date.’ I would say ‘went out with’ for a few months. That was how we termed it at the time.”

[snip]

Ford, in other words, claims that she had been going out with Squi for months before the alleged incident in the summer of 1982. Kavanaugh’s calendar from that year shows that he spent a lot of time with Squi as well. And Kavanaugh further alleges that he “may” have met Ford but that they “did not travel in the same social circle” and that “she was not a friend, not someone I knew.”

Ford went out with Squi (though earlier than the assault, it sounds like), and Kavanaugh spent tons of time with him. If you want to know how Kavanaugh and his buddies treated women that summer, you’d want to ask the women who were dating his buddies. But the letter signers apparently didn’t ask Ford.

Which means they asked a sample of women who remain close whether Kavanaugh treated women well, not the sample that might be best situated to attest to how he treated women that summer. (It’s also possible that Kavanaugh treated the girls from Georgetown Prep’s sister Catholic schools differently than they treated girls from other schools, though the letter includes women who attended both Catholic and non-Catholic schools.)

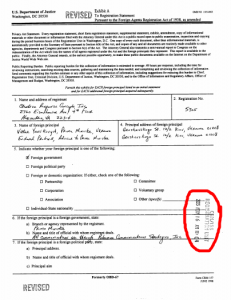

Of course, there’s a more nefarious possibility, the counterpart to the nefarious possibility that Ed Whelan targeted Squi precisely because he had learned who Ford was before her name became public and knew her connection to Kavanaugh went through Squi and knew that by falsely accusing Squi (who signed the male letter of support for Kavanaugh but has since gotten furious at being falsely accused of assault), he would discredit a key piece of evidence showing that Kavanaugh did travel in the same circles as Ford. That nefarious counterpart possibility is that enough women heard of the attempted rape at the time, knew which woman had been victimized, and so when calling around for supporters, avoided Ford.

The former is the more likely explanation: that the circle of women who — before knowing Ford’s identity, at least — were willing to make a show of a support for a powerful man who was about to become even more powerful, self-selected for those remain close to those who did have positive experiences with this crowd back in the day.

But if it is indeed true that Ford was not asked to sign, then it cannot be considered the proper sample to understand how Kavanaugh was treating women that summer.