It turns out that Ted Cruz is (partially) right: Some of the people who participated in January 6 are being treated as terrorists. But not all January 6 participants are terrorists.

Though, predictably, Cancun Ted misstates which insurrectionists have been or might be labeled as terrorists — in part out of some urgency to avoid calling himself or Tucker Carlson as such.

While some defendants accused of assaulting cops will, I expect, eventually be slapped with a terrorism enhancement at sentencing, thus far, the people DOJ has labeled terrorists have been key members of the militia conspiracies, including a number who never came close to assaulting a cop (instead, they intentionally incited a shit-ton of “normies” to do so).

Ted Cruz wants to treat those who threatened to kill cops as terrorists, but not those who set up the Vice President to be killed.

The problem is, even the journalists who know how domestic terrorism works are giving incomplete descriptions of how it is working in this investigation. For example, Charlie Savage has a good explainer of how domestic terrorism works legally, but he only addresses one of two ways DOJ is leveraging it in the January 6 investigation. Josh Gerstein does, almost as an aside, talk about how terrorism enhancements have already been used (in detention hearings), but then quotes a bullshit comment from Ethan Nordean’s lawyer to tee up a discussion of domestic terrorism as a civil rights issue. More importantly, Gerstein suggests there’s a mystery about why prosecutors haven’t argued for a terrorism enhancement at sentencing; I disagree.

As numerous people have laid out, domestic terrorism is defined at 18 USC 2331(5):

(5) the term “domestic terrorism” means activities that—

(A) involve acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States or of any State;

(B) appear to be intended—

(i) to intimidate or coerce a civilian population;

(ii) to influence the policy of a government by intimidation or coercion; or

(iii) to affect the conduct of a government by mass destruction, assassination, or kidnapping; and

(C) occur primarily within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States; and

As both Savage and Gerstein point out, under 18 USC 2332b(g)(5) there are a limited number of crimes that, if they’re done, “to influence or affect the conduct of government by intimidation or coercion, or to retaliate against government conduct,” can be treated as crimes of terrorism. One of those, 18 USC 1361, has been charged against 40-some January 6 defendants for doing over $1,000 of damage to the Capitol, including most defendants in the core militia conspiracies. Another (as Savage notes), involves weapons of mass destruction, which likely would be used if DOJ ever found the person who left bombs at the RNC and DNC. Two more involve targeting members of Congress or Presidential staffers (including the Vice President and Vice President-elect) for kidnapping or assassination.

If two or more persons conspire to kill or kidnap any individual designated in subsection (a) of this section and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy, each shall be punished (1) by imprisonment for any term of years or for life,

There’s very good reason to believe that DOJ is investigating Oath Keeper Kelly Meggs for conspiring to assassinate Nancy Pelosi, starting on election day and continuing as he went to her office after breaking into the Capitol, so it’s not unreasonable to think we may see these two laws invoked as well, even if DOJ never charges anyone with conspiring to assassinate Mike Pence.

Being accused of such crimes does not, however, amount to being charged as a terrorist. The terrorist label would be applied, in conjunction with a sentencing enhancement, at sentencing. But it is incorrect to say DOJ is not already treating January 6 defendants as terrorists.

DOJ has been using 18 USC 1361 to invoke a presumption of detention with militia leaders and their co-conspirators, starting with Jessica Watkins last February. Even then, the government seemed to suggest Watkins might be at risk for one of the kidnapping statutes as well.

[B]ecause the defendant has been indicted on an enumerated offense “calculated to influence or affect the conduct of government,” the defendant has been charged with a federal crime of terrorism as defined under 18 U.S.C §§ 2332b(g)(5). Therefore, an additional basis for detention under 18 U.S.C § 3142(g)(1) is applicable. Indeed, the purpose of the aforementioned “plan” that the defendant stated they were “sticking to” in the Zello app channel became startlingly clear when the command over that same Zello app channel was made that, “You are executing citizen’s arrest. Arrest this assembly, we have probable cause for acts of treason, election fraud.” Id. [my emphasis]

DOJ has invoked 18 USC 1361 as a crime of terrorism for detention disputes with the central Proud Boys conspirators as well. It’s unclear how broadly DOJ might otherwise do this, because another key figure who is an obvious a candidate for such a presumption, Danny Rodriguez (accused of tasing Michael Fanone and doing damage to a window of the Capitol), didn’t fight detention as aggressively as the militia members have, presumably because his alleged actions targeting Fanone clearly merit detention by themselves. That said, I believe his failed attempt to suppress his FBI interview, in which he admitted to helping break a window, was an attempt to limit his exposure to a terrorism enhancement.

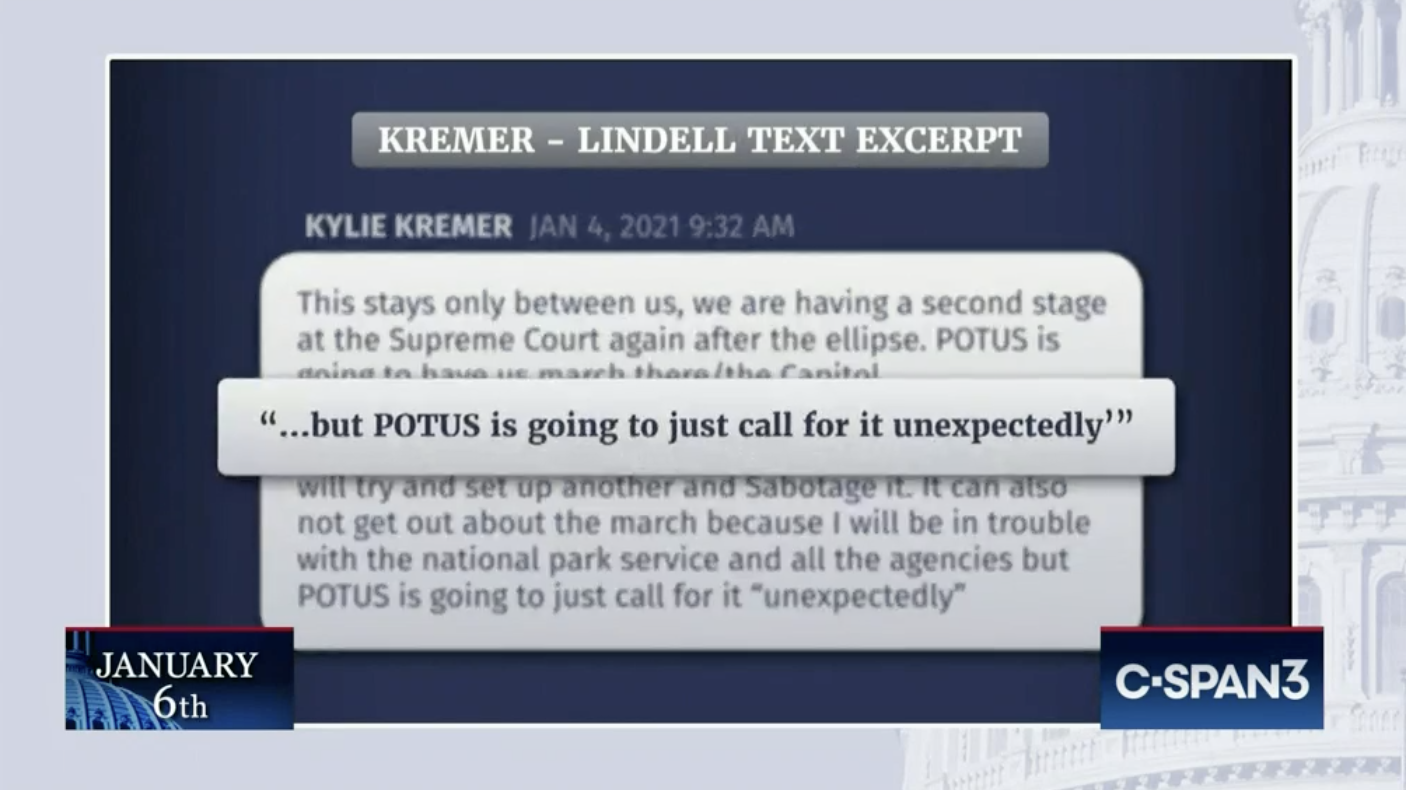

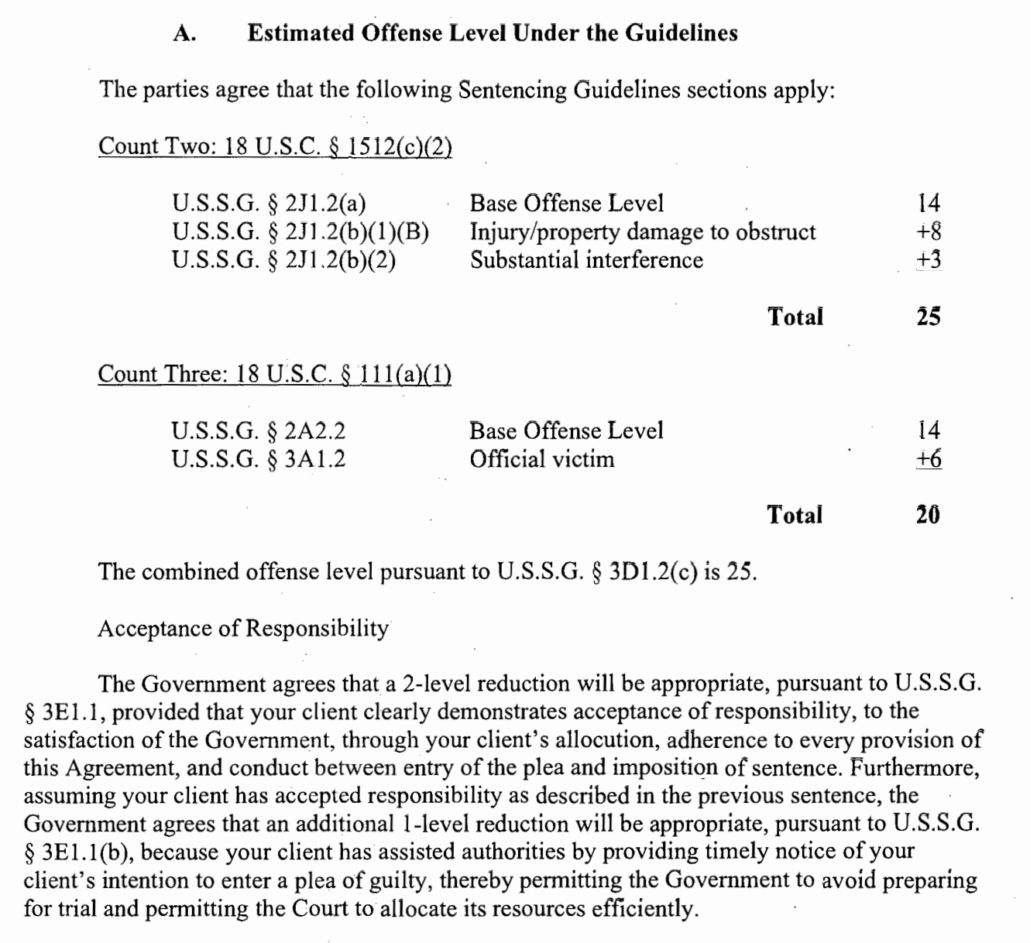

We have abundant evidence that DOJ is using the threat of terrorism enhancement to get people to enter cooperation agreements. Six of nine known cooperators thus far (Oath Keepers Graydon Young, Mark Grods, Caleb Berry, and Jason Dolan, Proud Boy Matthew Greene, and SoCal anti-masker Gina Bisignano) have eliminated 18 USC 1361 from their criminal exposure by entering into a cooperation agreement. And prosecutor Alison Prout’s description of the plea deal offered to Kurt Peterson, in which he would trade a 210 to 262 month sentencing guideline for 41 to 51 months for cooperating, only makes sense if a terrorism enhancement for breaking a window is on the table.

You can’t say that DOJ is not invoking terrorism enhancements if most cooperating witnesses are trading out of one.

For those involved in coordinating the multi-pronged breaches of the Capitol, I expect DOJ will use 18 USC 1361 to argue for a terrorism enhancement at sentencing, which is how being labeled as a terrorist happens if you’re a white terrorist.

But there is another way people might get labeled as terrorists at sentencing, and DOJ is reserving the right to do so in virtually all non-cooperation plea deals for crimes other than trespassing. For all pleas involving the boilerplate plea deal DOJ is using (even including those pleading, as Jenny Cudd did, to 18 USC 1752, the more serious of two trespassing statutes), the plea deal includes this language.

the Government reserves the right to request an upward departure pursuant to U.S.S.G. § 3A1.4, n. 4.

That’s a reference to the terrorism enhancement included in sentencing guidelines which envisions applying a terrorism enhancement for either (A) a crime involving coercion other than those enumerated under 18 USC 2332b or (B) an effort to promote a crime of terrorism.

4. Upward Departure Provision.—By the terms of the directive to the Commission in section 730 of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, the adjustment provided by this guideline applies only to federal crimes of terrorism. However, there may be cases in which (A) the offense was calculated to influence or affect the conduct of government by intimidation or coercion, or to retaliate against government conduct but the offense involved, or was intended to promote, an offense other than one of the offenses specifically enumerated in 18 U.S.C. § 2332b(g)(5)(B); or (B) the offense involved, or was intended to promote, one of the offenses specifically enumerated in 18 U.S.C. § 2332b(g)(5)(B), but the terrorist motive was to intimidate or coerce a civilian population, rather than to influence or affect the conduct of government by intimidation or coercion, or to retaliate against government conduct. In such cases an upward departure would be warranted, except that the sentence resulting from such a departure may not exceed the top of the guideline range that would have resulted if the adjustment under this guideline had been applied. [my emphasis]

The point is, you can have a terrorism enhancement applied even if you don’t commit one of those crimes listed as a crime of terrorism.

In a directly relevant example, the government recently succeeded in getting a judge to apply the latter application of this enhancement by pointing to how several members of the neo-Nazi group, The Base, who pled guilty to weapons charges, had talked about plans to commit acts of terrorism and explained their intent to be coercion. Here’s the docket for more on this debate; the defendants are appealing to the Fourth Circuit. This language from the sentencing memo is worth quoting at length to show the kind of argument the government would have to make to get this kind of terrorism enhancement at sentencing.

“Federal crime of terrorism” is defined at U.S.S.G. § 3A1.4, app. note 1 and 18 U.S.C. § 2332b(g)(5). According to this definition, a “federal crime of terrorism” has two components. First, it must be a violation of one of several enumerated statutes. 18 U.S.C. § 2332b(g)(5)(B). Second, it must be “calculated to influence or affect the conduct of government by intimidation or coercion, or to retaliate against government conduct.” 18 U.S.C. § 2332b(g)(5)(A). By § 3A1.4’s plain wording, there is no requirement that the defendant have committed a federal crime of terrorism. All that is required is that the crimes of conviction (or relevant conduct) involved or were intended to promote a federal crime of terrorism.

[snip]

To apply the enhancement, this Court needs to identify which specific enumerated federal crime(s) of terrorism the defendants intended to promote, and the Court’s findings need to be supported by only a preponderance of the evidence. Id.17

The defendants repeatedly confirmed, on tape, that their crimes were intended to promote enumerated federal crimes of terrorism. They intended to kill federal employees, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1114. Exhibit 19; Exhibit 20; Exhibit 28; Exhibit 33; Exhibit 34; Exhibit 44; Exhibit 45. They intended to damage communication lines, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1362. Exhibit 37. They intended to damage an energy facility, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1366(a). Exhibit 30; Exhibit 35; Exhibit 36; Exhibit 45. They intended to damage rail facilities, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1992. Exhibit 29; Exhibit 30; Exhibit 38; Exhibit 45. And they intended to commit arson or bombing of any building, vehicle, or other property used in interstate commerce, in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 844(i). Exhibit 45.

Furthermore, there can be no serious dispute that the defendants’ intentions were “to influence or affect the conduct of government by intimidation or coercion.” Coercion and capitulation were core purposes of The Base. And specific to the defendants, they themselves said this is what they wanted. Exhibit 39 (“Desperation leads to martyr. Leads to asking what we want. Now that’s where we would have to simply keep the violence up, and increase the scope of our demands. And say if these demands are not met, we’re going to cause a lot of trouble. And when those demands are met, then increase them, and continue the violence. You just keep doing this, until the system’s gone. Until it can’t fight anymore and it capitulates.”). It was their express purpose to “bring the system down.” Exhibit 36

Given how many people were talking about hanging Mike Pence on January 6, this is not a frivolous threat for January 6 defendants. But as noted, such a terrorism enhancement doesn’t even require the plan to promote assassinating the Vice President. It takes just acts dangerous to human life that are a violation of the criminal laws of the United States and an attempt to coerce the government.

Contra Gerstein, I think there’s a pretty easy explanation for why the government hasn’t asked for a terrorism enhancement yet. The way the government is relying on obstruction to prosecute those who intended to prevent the peaceful transfer of power sets up terrorism enhancements for some of the most violent participants, but we’ve just not gotten to most of the defendants for whom that applies.

Thus far, there have been just three defendants who’ve been sentenced for assault so far, the acts “dangerous to human life” most at issue: Robert Palmer, Scott Fairlamb, and Devlyn Thompson. But Palmer and Thompson pled only to assault.

Fairlamb, as I noted at the time, pled guilty to both assault and obstruction. Unlike the two others, Fairlamb admitted that his intent, in punching a cop, was to, “stop[] or delay[] the Congressional proceeding by intimidation or coercion.”

When FAIRLAMB unlawfully entered the Capitol building, armed with a police baton, he was aware that the Joint Session to certify the Electoral College results had commenced. FAIRLAMB unlawfully entered the building and assaulted Officer Z.B. with the purpose of influencing, affecting, and retaliating against the conduct of government by stopping or delaying the Congressional proceeding by intimidation or coercion. FAIRLAMB admits that his belief that the Electoral College results were fraudulent is not a legal justification for unlawfully entering the Capitol building and using intimidating [sic] to influence, stop, or delay the Congressional proceeding.

Fairlamb, by pleading to assault and obstruction, admitted to both elements of terrorism: violence, and the intent of coercing the government.

On paper, Fairlamb made a great candidate to try applying a terrorism enhancement to. But the sentencing process ended up revealing that, on the same day that Fairlamb punched a cop as part of his plan to overturn the election, he also shepherded some cops through a mob in an effort, he said with some evidence shown at sentencing, to keep them safe.

That is, on paper, the single defendant to have pled guilty to both assault and obstruction looked like a likely candidate for a terrorism enhancement. But when it came to the actual context of his crimes, such an enhancement became unviable.

I fully expect that if the January 6 prosecution runs its course (a big if), then DOJ will end up asking for and getting terrorism enhancements at sentencing, both for militia members as well as some of the more brutal assault defendants, both for those who plead guilty and those convicted at trial. But in the case of assault defendants, it’s not enough (as Ted Cruz says) to just beat cops. With a goodly number of the people who did that, there’s no evidence of the intent to commit violence with the intent of disrupting the peaceful transfer of power. They just got swept up in mob violence.

I expect DOJ will only ask for terrorism enhancements against those who made it clear in advance and afterwards that their intent in resorting to violence was to interrupt the peaceful transfer of power.

But until that happens, DOJ has already achieved tangible results, both in detention disputes and plea negotiations, by invoking crimes of terrorism.