America Just Failed the Test of Responding to Trump’s Politicized Prosecutions

Let’s imagine that, two years from now, Pam Bondi rolls out charges against some onetime adversary of Donald Trump. To the extent that journalists will still be employed and reading court filings, to the extent that prosecutors under Emil Bove (who at SDNY oversaw a team sanctioned for discovery violations) comply with discovery requirements, the adversary in question learns the following about his prosecution:

- The case started when an investigator started looking into a transnational trafficking network

- The investigator discovered that the prominent adversary had paid one of the sex workers trafficked in the network

- Rather than pursuing the traffickers, the investigator used the payment for sex as cause to open an investigation

- Of course, no one is going to charge a John … so the investigator starts pulling divorce records and four year old tax returns to try to move from that payment for sex work to something that can be charged

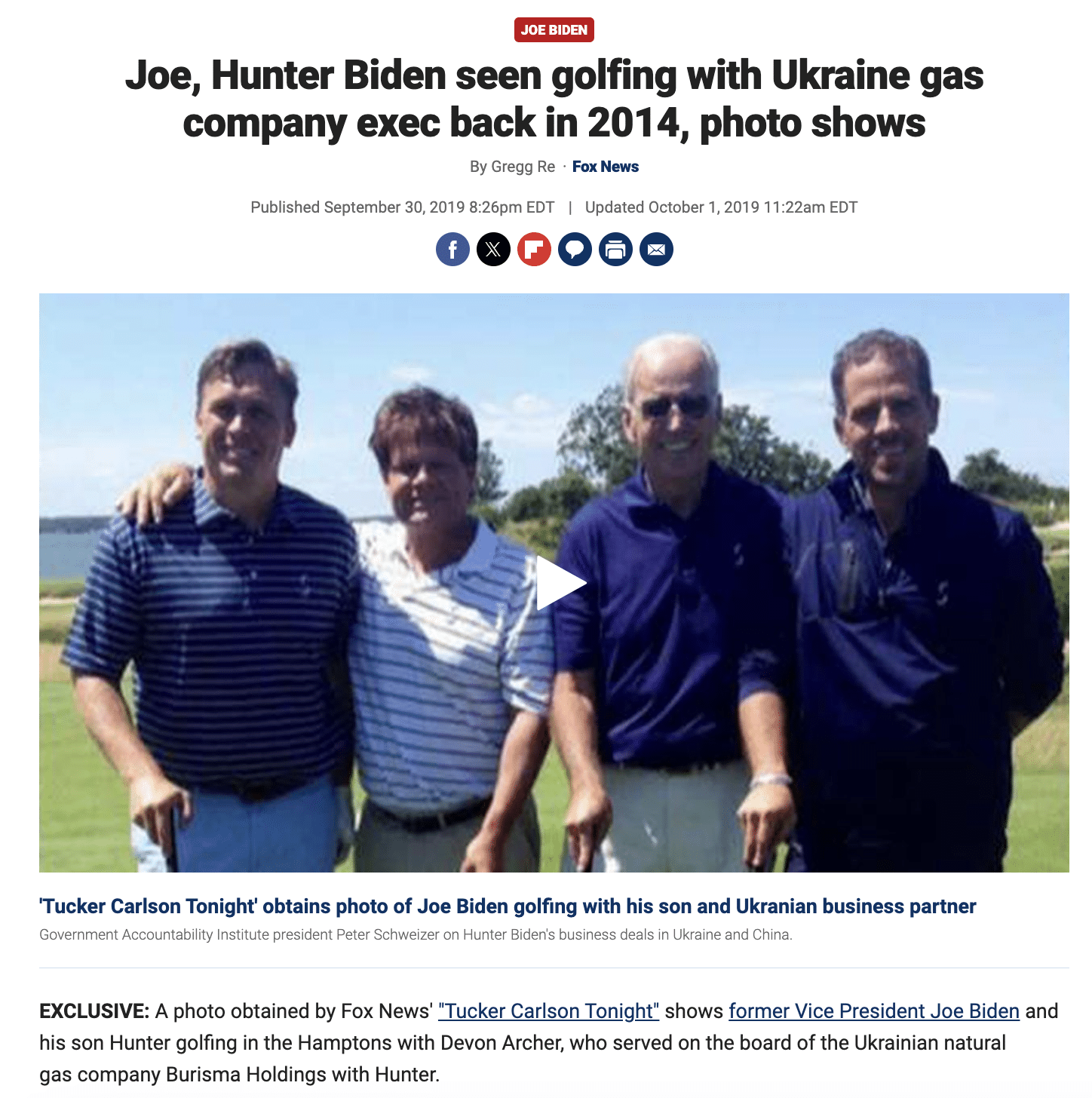

- Then the investigator started incorporating oppo research from Peter Schweizer into his investigation

- Kash Patel’s FBI set up protected ways to accept tips from Trump supporters who’ve doctored documents to create a crime

- Trump called up Bondi and told her to take more aggressive steps

- Trump called up foreign leaders asking for help on this prosecution

- Bondi then set up a way to launder that information from foreign sources, including known spies, into the investigation of the adversary

- Patel’s FBI asked a partisan informant to fabricate claims against the adversary

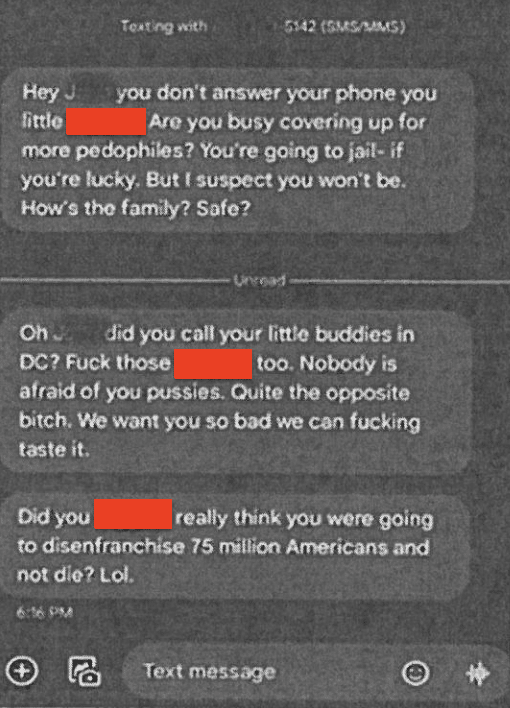

- Trump publicly called out prosecutors — resulting in them and their children being followed — because they had not yet charged his adversary

- Ultimately, the adversary got charged on 5-year old dirt, and only then, after charging, did prosecutors quickly do the investigative work to win the case at trial

Now, as I’ve described it, you surely imagine you’d say, wow, that looks like a thoroughly corrupt prosecution, a clear case of Trump using DOJ to punish his adversaries.

Right?

It’s not so much that investigators didn’t, after the fact, find a crime to charge. They did. If you investigate most high profile people long enough, you’ll find something to charge, particularly if multiple people come to DOJ with doctored evidence to help create that crime.

It’s that someone found the name of an adversary in the digital records of crimes that were more important to investigate, and instead of pursuing that crime, used the electronic record as an excuse to keep looking until they found some evidence of a crime against Trump’s adversary.

Everyone would recognize that’s what happened, right?

Of course not. Of course no one would recognize that that was a political prosecution.

We need no further proof than the fact that none of those very same details showed up in any of the coverage of the Hunter Biden investigation. Not now that he has been pardoned. Not when all these details came out last year. Not in any of the retrospectives of the times Trump demanded investigations on his adversaries.

What will happen instead is that a bunch of self-important DC scribes will chase the most salacious allegations, provide endless headlines about sex workers and wild parties. The DC scribes will ignore every detail about the legal investigation — every one!! — and instead use the prosecution as an opportunity to sell political scandal. And also, they will point to their Tiger Beat coverage as proof, they say, they are not politically biased.

Rather than diligently rooting out the obviously politicized prosecution, the press will be complicit in it.

And rather than deciding that the adversary was the target of an obviously politicized prosecution, American public opinion would instead decide that the adversary was icky, and because he is icky, his statements about Trump cannot be credited.

That is what political prosecutions look like. That is, of course, precisely what the Hunter Biden prosecution was (ignoring the assurances from prosecutors who say no one with the fact set Hunter faced would be charged). Every single bullet has an analogue in the Hunter Biden case. That obviously political prosecution is what happened.

Once the GOP got the House majority, they did nothing else but platform these claims, which a different set of self-important scribes treated as an interesting process story, not an obvious case of a great abuse of government power.

And now that Biden has pardoned his son, the very same self important scribes who ignored all the signs this was a political prosecution, are giving non-stop coverage to a pardon that — unlike those of Trump’s Coffee Boy, National Security Adviser, campaign manager, personal lawyer, and rat-fucker — are not about self-protection, most with no mention of all the evidence Trump ordered up this prosecution to target Joe Biden.

The question is, what are we going to do about this, now that we have rock solid proof the press establishment is not only incapable, but wildly uninterested, in rooting out this kind of politicized prosecution — at least not when they can instead sell scandal?

In the face of seeing Pam Bondi and Kash Patel preparing to redouble efforts to find politicized prosecutions against Donald Trump’s adversaries, Joe Biden chose to end the process, with his son, at least.

I’m actually on the record opposing the pardon — but not for the reasons everyone else is. I don’t think pardoning Hunter in this circumstance is corrupt. I take Biden at his word that he changed his mind about pardoning Hunter. I’m far more interested in Trump admitting he was lying about his plans to implement Project 2025 than that Biden reneged on assurances no one much believed anyway.

I oppose the pardon because it eliminates Hunter’s standing to appeal and with those appeals to begin telling the story that the media chose to ignore. I oppose the pardon because if we don’t start laying out how Trump already politicized DOJ while there’s a good base of legitimate judges in place, it’ll be far too late.

And don’t get me wrong. I think Biden fucked this one up. Not just for saying he wouldn’t pardon Hunter, but for not taking action far earlier — like firing David Weiss the day he was inaugurated, citing Trump’s first impeachment, or pardoning Hunter and firing Weiss on November 6 — to do something about this. I think Merrick Garland shouldn’t have given Weiss himself SCO status (not least, because Weiss continues to investigate crimes — the alleged attempted framing of Joe Biden by Alexander Smirnov — to which he is a witness). I think Garland’s supervision of Special Counsels allowed the abuse of the system, repeatedly.

I’ve never, as far as I’m aware, spoken with Hunter Biden. I have, however, spoken to a good number of the people who were and who would be politically prosecuted in Trump’s second term (not including myself, of course). And the thing I’ve learned from them is because the press is complicit in their politicized prosecution, it guarantees they’ll be isolated, regardless of guilt or innocence. Because the press has unquenchable thirst for lazy dick pic sniffing, they don’t do the work of reading the court filings. Because the press thirsts for a false appearance of both sides neutrality, they’re always on the hunt for something to fit into their both sides scandal box.

And meanwhile, those very same self-important scribes were largely silent in 2020 when Trump pardoned his way out of Russian trouble, and even more silent in 2024 when they could have explained to voters that he had done so.

Whatever else you think about the Hunter Biden case and the way Joe Biden pardoned him, it is crystal clear proof that the thing defenders of democracy swear they’ll do in a second Trump term — rise to the defense of those targeted for political prosecution — they already failed to do. Whatever you think about the Hunter Biden case, the vast majority of people talking about it have absolutely no clue that it is precisely what people fear in Trump’s second term, not (just) because Hunter was charged in two indictments when others would not be, but because Trump and his people repeatedly ordered up this prosecution.

Update: Peter Baker, who wrote an otherwise thorough piece during the election about Trump’s corruption which ignored Hunter, claims to be unable to tell whether Biden’s claim that Hunter’s prosecution was politicized is true or not.

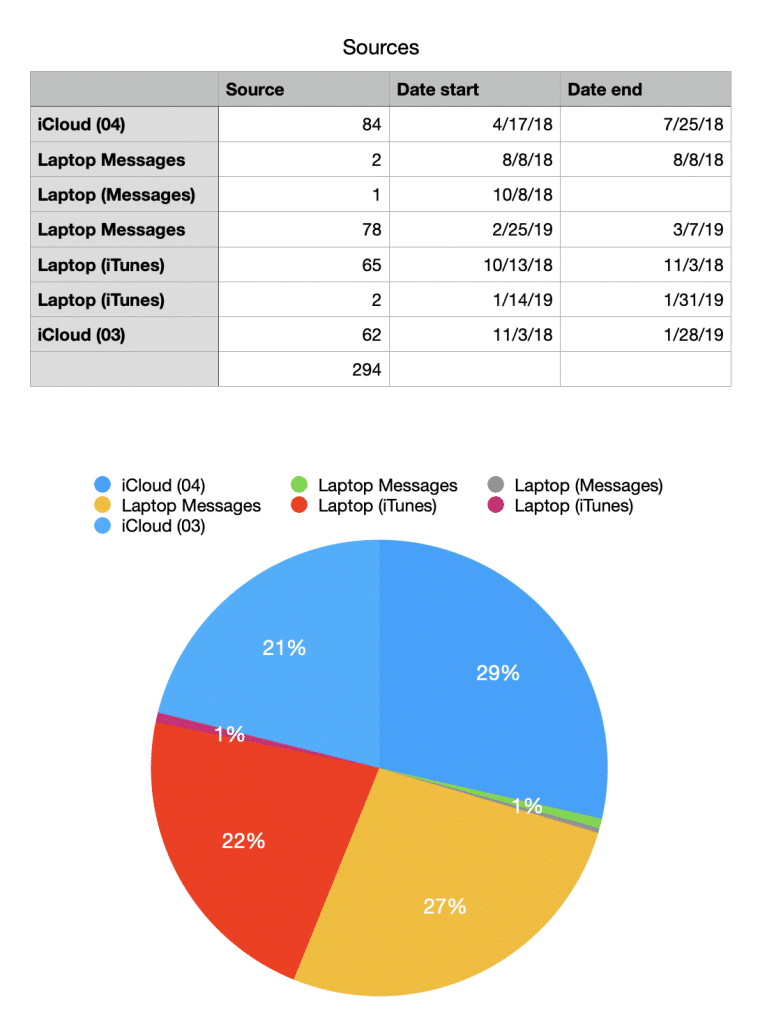

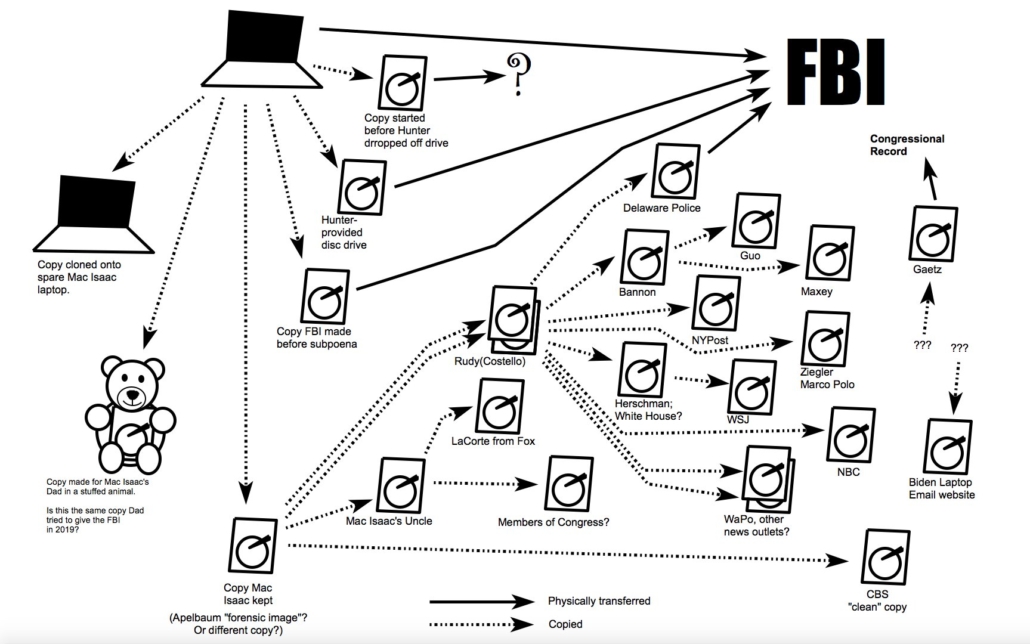

Update: Here’s a copy of a white paper Hunter’s attorneys released to describe the politicization of the case. It adds the Parnas and Scott Brady allegations to the stuff in the selective prosecution motions.