By my rough count, Judge Tanya Chutkan has presided over the cases of more than 25 January 6 defendants, in addition to Donald Trump. Nevertheless, Trump keeps trying to lecture Chutkan about what happened, often by pointing to reports from journalists who have not otherwise covered the investigation closely.

Contrary to their false claims about how much video she has seen, Judge Chutkan knows these details far better than Trump’s attorneys.

For example, Trump keeps pointing to a December 2021 piece from Will Arkin to argue, using very dated numbers regarding the investigation, just one percent of his mobsters qualify as insurrectionists.

The Secret Service and the FBI estimated that at least 120,000 Americans gathered on the Mall for President Trump’s speech. 6 Government agencies estimated that about 1,200 people—at most 1% of the size of the crowd gathered to listen to President Trump—entered the Capitol, and a smaller percentage than that committed violent acts. 7 Thus, we can easily conclude that well over 99% of the attendees at President Trump’s speech did not engage in the events at the Capitol. Moreover, as the Indictment recognizes, a crowd had gathered at the Capitol before President Trump finished speaking, further proving he had nothing to do with those events.

6 William M. Arkin, Exclusive: Classified Documents Reveal the Number of January 6 Protestors, NEWSWEEK (Dec. 23, 2021), at https://www.newsweek.com/exclusive-classified-documentsreveal-number-january-6-protestors-1661296. The January 6 Committee estimated the crowd on the Mall at 53,000, while President Trump estimated it at 250,000. Compare Final Report, SELECT COMMITTEE TO INVESTIGATE THE JANUARY 6TH ATTACK ON THE UNITED STATES CAPITOL (Dec. 22, 2022), 585, at https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-J6-REPORT/pdf/GPO-J6-REPORT.pdf with Read Trump’s Jan. 6 Speech, A Key Part of Impeachment Trial, NPR (Feb. 10, 2021), at https://www.npr.org/2021/02/10/966396848/read-trumps-jan-6-speech-a-key-part-ofimpeachment-trial (emphasis added).

7 Id. (“[T]he facts seem to indicate that as few as one percent of the people who were there fit the label of insurrectionist.”).

There are a slew of problematic assumptions in Arkin’s piece (as well as the follow-up piece that appears to be the actual source cited in footnote 7): about the relationship between militias and others, about the role of non-militia organized groups like QAnon or anti-vaxxers, about the role and increasing percentage of military participants.

The most important misconception is that only people who entered the building, as distinct from the often more violent crowds outside it or Proud Boy seditionists orchestrating things from afar, could be an insurrectionist.

Plus, Arkin’s 2021 numbers were outdated at the time — most outlets put the number of insiders at 2,000 to 2,500 at the one year anniversary and the Sedition Hunters have identified 3,200 specific people who went inside the Capitol (though this includes people, including at least one WaPo journalist, who weren’t rioters).

Given Trump’s reliance on such outdated numbers, however, I wanted to look at a filing in the latest challenge to one of the geofence warrants used in the investigation, this time from Isreal Easterday, a Confederate-flag toting rioter who sprayed two cops before entering the Capitol through the east door.

There have already been two failed challenges to geofence warrants used in the investigation. In August 2022, then-Chief Judge Beryl Howell rejected Matthew Bledsoe’s challenge to a geofence of those who live streamed to Facebook during the riot; he is appealing his conviction, but not that ruling. In January, then-presiding FISA Judge Rudolph Contreras rejected David Rhine’s challenge to the Google geofence tied to voluntary use of Google’s Location History service (there’s no FISA component to this, but FISA judges see more novel Fourth Amendment issues). Rhine does appear to be including that ruling in his appeal, in which his initial brief is due in February.

Like Rhine, Easterday is challenging the Google geofence, but from a Fourth Amendment standpoint, he is different than Rhine in two key ways. First, the investigation into Rhine started from some tips called in as early as January 10, 2021; the FBI didn’t need the Google geofence to find him, though it made it easier to pinpoint video of his path through the Capitol.

With Easterday (probably because two distinctive aspects of his appearance changed that day — he dropped his flag and took off his hat — making it harder to track him), the first really good lead on his identity was the geofence.

The second difference between Rhine and Easterday arises from the technicalities of how the FBI did the geofence.

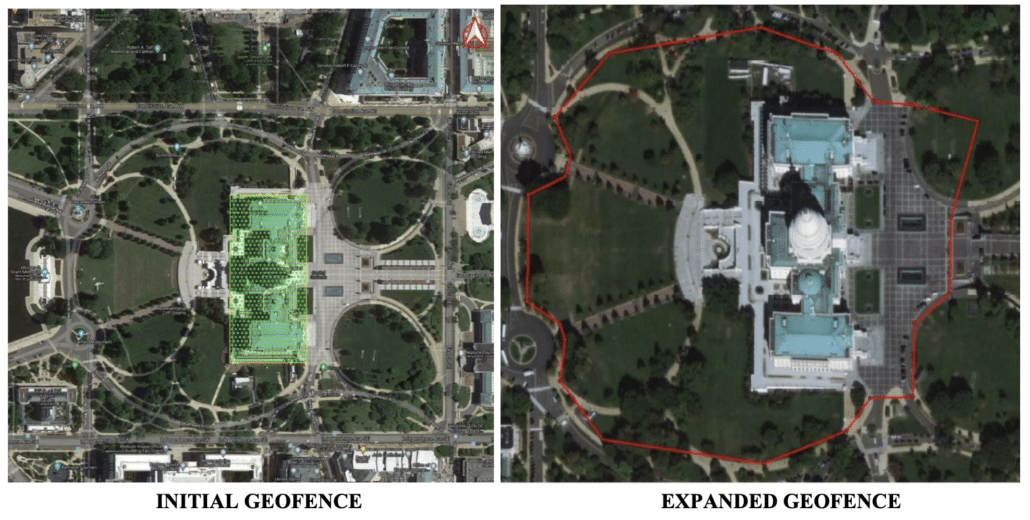

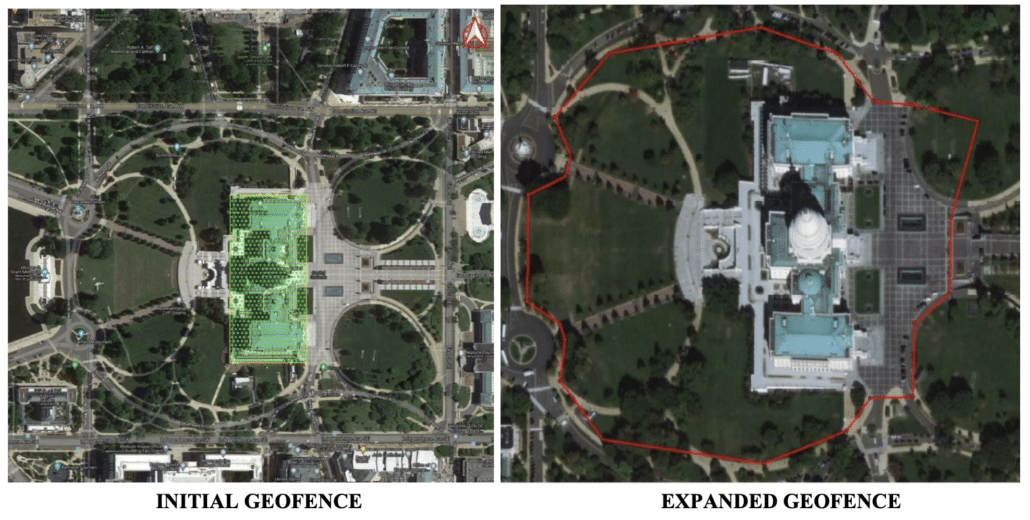

The FBI did three rounds of geofence with Google. In the first, starting with a January 13, 2021 warrant to Google, they:

- Obtained the identifiers for all the phones that hit the geofence during the riot

- Took out the identifiers that were present in the building in the 15 minutes before and after the riot (assuming those were people who were lawfully present in the Capitol)

- Sorted out hits that were in places (for example, areas where surveillance footage showed no rioters to be present) inconsistent with unlawful activity

- Eliminated identifiers without at least one hit entirely within the Capitol factoring in margin-of-error radius

- Added back in identifiers with lower confidence radius that deleted Location History with the week after the attack

- Asked Google to deanonymize that data

For the second round, they submitted a second request for deanonymization on April 14, based on the logic that those for whom there were only low confidence hits within the Capitol would be high confidence hits for the larger restricted area.

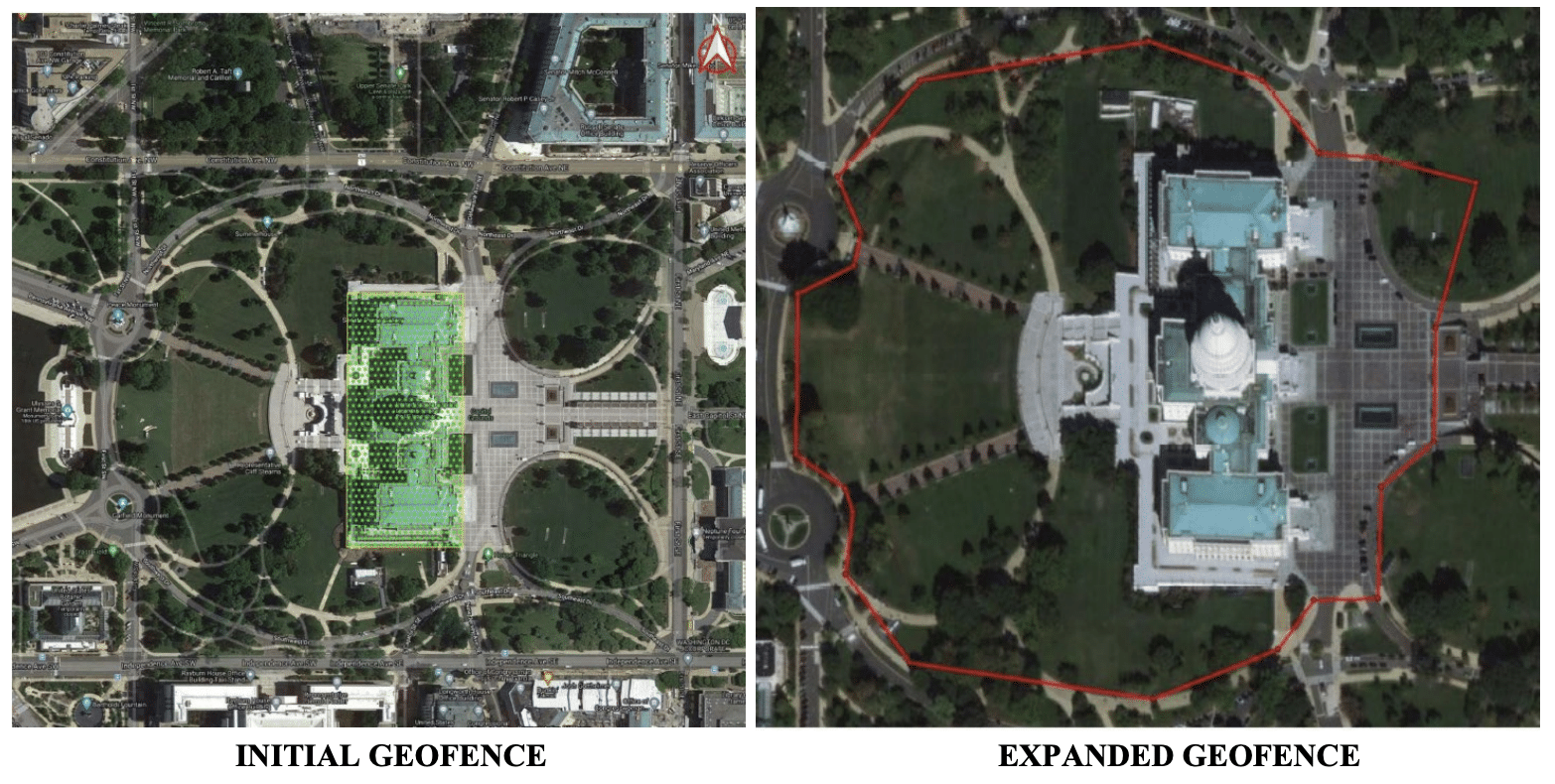

Based on the same logic, on May 21, 2021, the FBI obtained a second geofence warrant to include (per Easterday’s filings) the entire restricted area on January 6.

This time, to cull the data, they:

- Obtained the identifier for all the phones that hit the geofence during the riot

- Removed identifiers previously deanonymized

- Took out the lawfully present identifiers either voluntarily identified by Congressional offices or obtained by law enforcement

- Removed identifiers present in the 15 minutes before or after the riot

- Eliminated identifiers without at least one hit entirely within the restricted grounds

- Asked Google to deanonymize that data

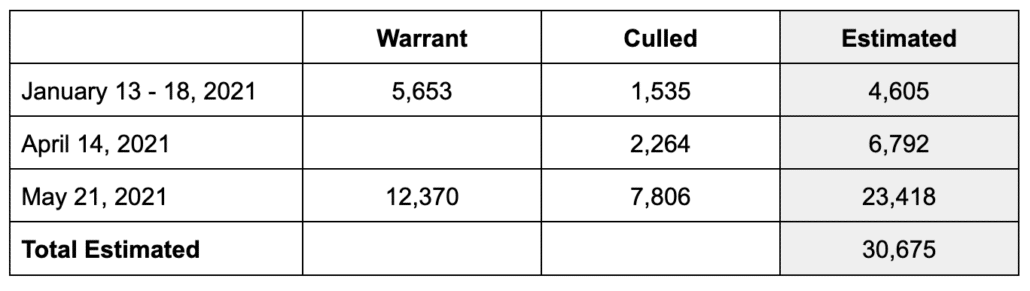

Rhine’s phone identifier was included in the first batch of identifiers the FBI asked to be deanonymized, a group of about 1,500 identifiers; Easterday’s was not. His phone was included in the second batch deanonymized, an additional 2,200 identifiers obtained in the first warrant. His phone was also IDed in the second warrant, but by that point had already been deanonymized.

The details of how the Google geofence worked were described in filings in the Rhine case (see this post and this post), but because Easterday was not identified until the second batch, the second cull gets more attention in Easterday’s filings.

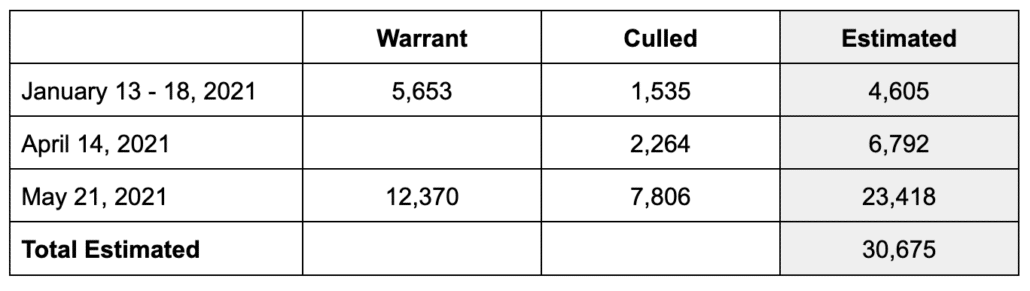

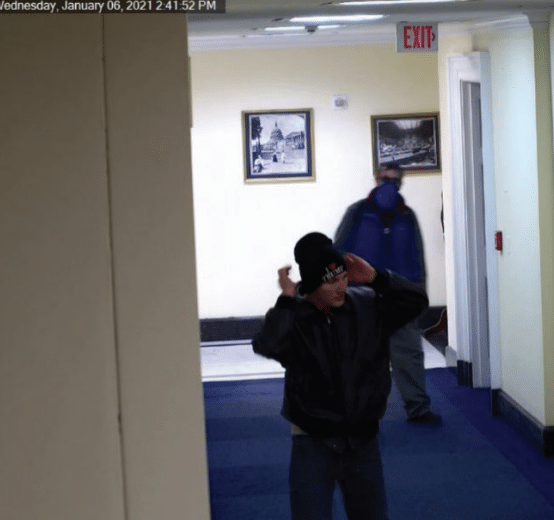

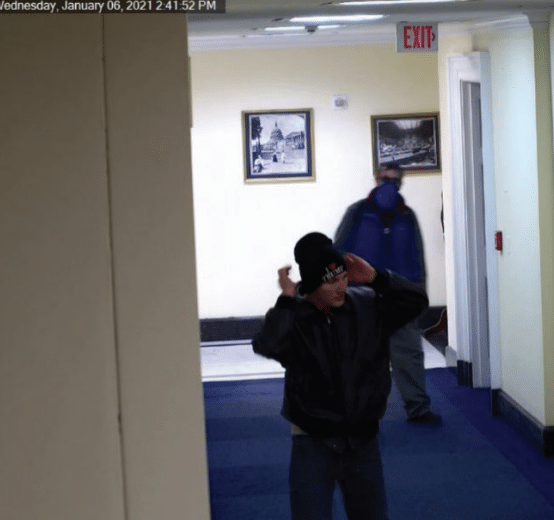

Easterday did enter the Capitol. There are pictures of him wandering hallways and stairs. On October 26, a jury convicted him of trespassing inside the Capitol, 40 USC 5104, along with the more serious assault and riot felonies he committed outside the building.

Easterday was only inside the Capitol itself for 12 minutes — he entered at 2:39 and exited at 2:51; Easterday entered three minutes before Rhine but left 13 minutes before Rhine. But he would have been at the east door — not inside the Capitol, but helping to violently break into it — for at least 22 minutes; the assault on one of the cops was captured in video that starts at 2:17.

There are a number of possible explanations for why Easterday phone would not have had a high confidence hit inside the Capitol geofence but did trigger the broadened geofence. For example, the original hit or hits on Easterday’s phone may have been in a location (such as the east door) where the confidence radius of the location was partially outside the Capitol itself. Some of the relevant hits were surely entirely within that area outside the Capitol but inside the restricted area that day. As the government noted in their response to this challenge, being in that area was also a trespassing crime, 18 USC 1752, even if DOJ charged fewer of the people who were in that area. The jury convicted Easterday of that crime, too.

The government provided a supplement answering specific questions Chief Judge James Boasberg posed after the guilty verdict that provides more possible explanations why Easterday did not trigger the geofence within the building at high confidence. For example, it describes that iPhones capture a lot less activity in Location History than Androids do.

[Location History] is sometimes collected automatically, but is primarily and most frequently collected when a user is doing something with his or her device that specifically involves location information (such as following Google Maps directions or taking photographs or videos that record location as part of their metadata).

Moreover, in the government’s experience examining Google LH returns, the range of activities that generate a LH point is narrower on Apple’s iPhones than Android phones. Apple iPhones apparently collect LH data primarily when the user is specifically using Google Maps.

[snip]

In contrast, Android phones can collect LH data when the user uses a wider array of Google-based applications, or even when the device is not in use at all, such as when it is sitting on a user’s bedside table overnight. Additionally, if an Android phone detects that a user is moving, the Android phone specifically and automatically requests location data from the server about every two minutes, leading to a LH data point being collected by Google. However, if the phone determines that the user is standing relatively still, or remaining within the same Wi-Fi network’s range, Android phones will request location data much less frequently, as the phone is effectively not moving. Similarly, devices will not automatically request location data from the server—or will do so less frequently—when they are low on battery.

Easterday appears to have made a call while inside the building (which would trigger a different kind of location data, but data that DOJ only obtained with individualized warrants), but that’s less likely to be captured in Location History than taking a picture would.

Judge Boasberg’s request for more information — an order he made after the guilty verdict — appears to stem, in significant part, from the fact that FBI’s initial exclusion set of 215 people is obviously a mere fraction of the people who were lawfully in the Capitol that day.

(2) how could the Control List searches for the Initial Google Geofence Warrant have generated hits for only 215 unique devices/accounts when Google applications are so ubiquitous and presumably between 1,500-2,000 people were lawfully present in the Capitol building in the time periods before and after the riot?

It its earlier filings, DOJ used a dated stat that only 30% of Google users actually use the Location History service, a service that takes several steps to turn on. In this filing, DOJ argues that as the proportion of iPhone users increase, the number of people who trigger Location History will be smaller still, unless they’re using Google maps.

Boasberg is suggesting (and DOJ is not contesting) that their initial exclusion effort may only have included about 15% of those lawfully in the Capitol. While there would be some subset of people lawfully present who weren’t excluded in the first batch (people who were not moving in the 15 minutes before and after but who fled or took pictures during the riot, for example), this filing suggests all these numbers are low — very low.

If just one third of the people who entered the building could be expected to trigger the Google geofence, then the number who entered may be well over 4,000 (a reasonable number given the number Sedition Hunters have IDed).

If just a third of the people who were at the Capitol but not necessarily taking pictures inside it triggered the Google geofence, that number might be closer to 7,000 additional bodies, including those assaulting cops. And there could be another 23,000 people outside the Capitol — some no more than MAGA tourists, but others among the most violent people that day.

Using the Arkin numbers that were outdated when he published them in December 2021, Trump claims that, “we can easily conclude that well over 99% of the attendees at President Trump’s speech did not engage in the events at the Capitol.”

That’s not what the geofence shows. Using the same 120,000 number he uses for his own calculations, about one in ten were right at the building and a quarter may have made it to restricted ground, and the numbers could be double that.

One thing is clear though: the violent mobsters literally carrying the banner of insurrection as they attack cops may not be the ones you’ll find taking pictures inside the Capitol. And once you figure that out, the numbers of potential Trump insurrectionists starts to grow.

And Judge Chutkan knows that.

Take, Robert Palmer, whom Trump raised to complain that Chutkan had presided over the prosecution of someone who said he went to the Capitol at Trump’s behest, where he serially assaulted cops because he believed he needed to stop the voter certification. Robert Palmer never entered the Capitol. But it’s quite clear he believes Trump sent him.

Update: Distinguished between the two trespassing crimes to show one can be applied to both locations.

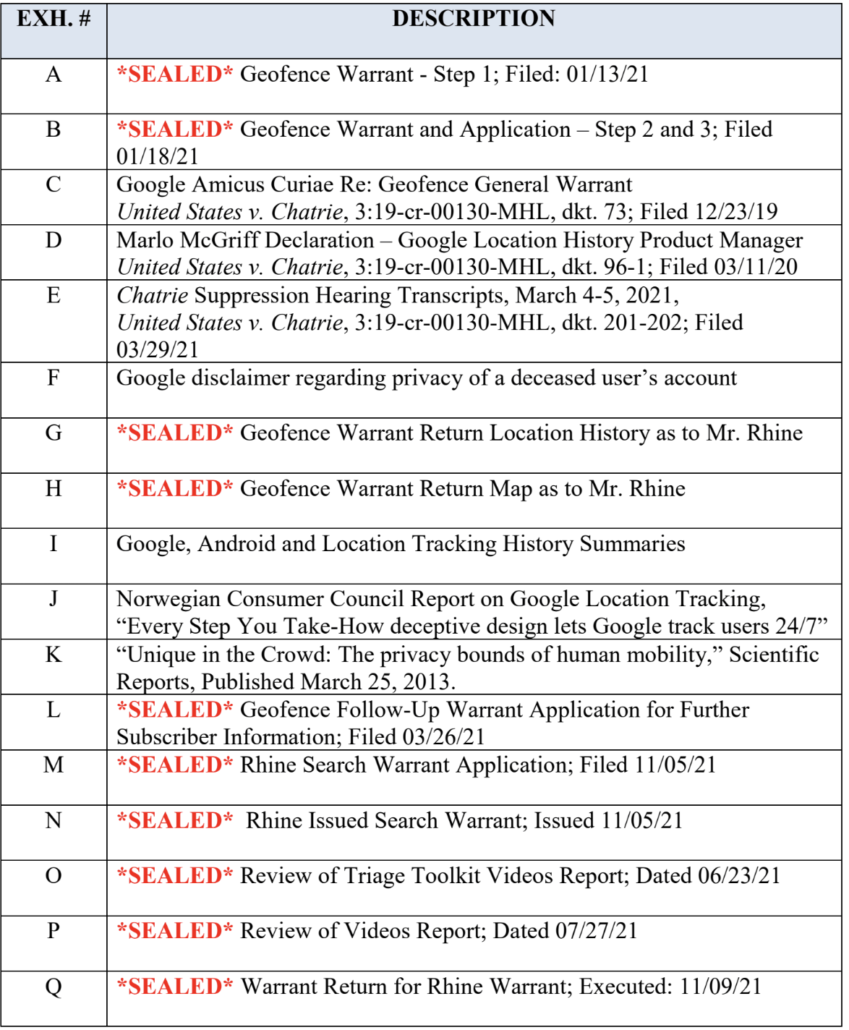

Timeline Easterday Google Geofence Challenge

June 30, 2023: Motion to Compel, Declaration

August 22, 2023: Opposition Motion to Compel

September 26, 2023: Motion to Suppress Geofence

October 10, 2023: Opposition Motion to Suppress

October 17, 2023: Reply Motion to Suppress

October 26, 2023: Guilty Verdict

November 25, 2023: Supplement Opposition Motion to Suppress