Trevor McFadden Uses Stormtroopers to Justify His Promise to Let Jan6ers Off Easy

In the middle of a rather cursory opinion rejecting David Judd’s claim that he has been selectively prosecuted as compared to Portland rioters, Trevor McFadden cites this AP story to support a claim that “thousands” of protestors gathered every night in Portland.

For the first prong, Judd argues that he is similarly situated to multiple defendants who faced charges in the District of Oregon. Those defendants rioted outside the Mark Hatfield Federal Courthouse in Portland during the summer of 2020. See Def.’s Mot. at 2–4. The riots erupted after the death of George Floyd in May 2020 and raged for months. Thousands gathered nightly, vandalizing the courthouse and hurling objects at federal agents guarding it. Officers responded with tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse rioters, but the riots continued, causing havoc. See generally Mike Balsamo and Gillian Flaccus, On Portland’s Street: Anger, fear, and a fence that divides, AP News (July 27, 2020). [my emphasis]

In fact, the story says that the 4,000 gathered on that particular night was the largest crowd federal officers had seen, not that those kinds of numbers consistently came out.

Under orders to protect the courthouse — federal property that has been increasingly targeted as the city’s protests against racial injustice march on — the agents were accustomed to the drill. But tonight, the crowd was huge, estimated at 4,000 people at its peak and the largest they had seen.

The numbers the AP cites for those involved in violence or those that remained after officers responded is smaller.

As she spoke, small pods of three to four protesters dressed in black circulated in the crowd, stopping every few minutes to point green laser beams in the eyes of agents posted as lookouts on porticoes on the courthouse’s upper stories.

[snip]

Outside, hundreds of protesters surged back from the courthouse with each new round of tear gas, dumped saline solution and water into their stinging eyes, vomited or doubled over to catch their breath, then regrouped to march back to the fence.

“Stay together, stay tight! We do this every night!” they chanted.

The protesters’ numbers, however, were half what they had been just a few hours before.

[snip]

Tear gas canisters bounced and rolled in the street, their payload fizzing out into the air before protesters picked them up and hurled them back over the fence at the agents, who held their ground.

A woman weaved through the crowd of the few hundred people who remained and told someone on the phone, “We’ve reached some kind of stand-off, I think.”

When the federal agents finally came, they came with force. [my emphasis]

So it actually doesn’t support McFadden’s claim, which is probably why he cites it, “generally:” to hide that in fact he doesn’t have a source for his claim about sustained crowds of thousands of rioters (though at that time in July 2020, protests did remain large for a brief period).

The article is not one David Judd cited himself in either his original motion or his reply — perhaps because the AP story makes it crystal clear why firecrackers are so dangerous when thrown at cops, as he is accused of doing.

That McFadden’s clerk did research on their own on the Portland unrest and that McFadden’s clerk chose this particular article — by one of Billy Barr’s favorite reporters and covering unrest overnight on July 24 to 25, 2020 — is really telling. That’s true because the story portrays details directly pertinent to Judge McFadden’s opinion that should, but do not, appear in his opinion. And it’s also true because McFadden’s clerk relied on the AP story and not this NYT story from the same week covering the same unrest, which I’ll come back to.

At the core of Judd’s argument is that those charged with violence in Portland got (starting even under Billy Barr) and continue to get (under Merrick Garland) Deferred Prosecution Agreements, rather than the felony charges Judd is facing. To make his argument, Judd cherry-picked some cases and complained that he wasn’t being treated as nicely as a guy who (unlike Judd) was charged with a crime of terrorism, but whose charges were dismissed when the guy was murdered. DOJ pointed out more problems with Judd’s claims, including that he had claimed felony assault charges were misdemeanors, left out cases similar to his that were charged similarly, and ignored cases where DOJ deferred to state prosecution.

But DOJ professed to be unaware of the reason why three cases on which Judd (and McFadden) focused closely led to a DPA.

Further, contrary to his claims, each of the three cases Judd cites in his motion as examples where a defendant had only been charged with a misdemeanor actually involved a felony charge to 18 U.S.C. § 111(a). Although it is true that each case was eventually dismissed by the government for unknown reasons (typically after the defendants repeatedly agreed to waive their rights to a preliminary hearing or indictment over a period of months), all were initially facing felony charges. [my emphasis]

DOJ’s claim not to know why these cases entered into a DPA is just as suspect as McFadden’s choice of a source for the crowd sizes in Portland.

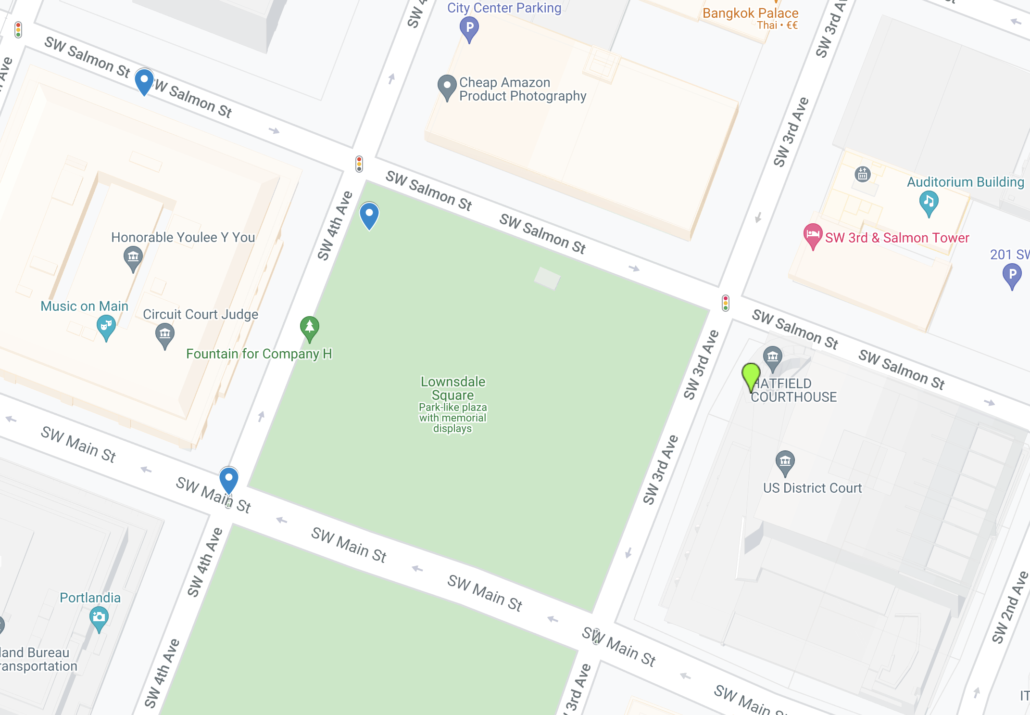

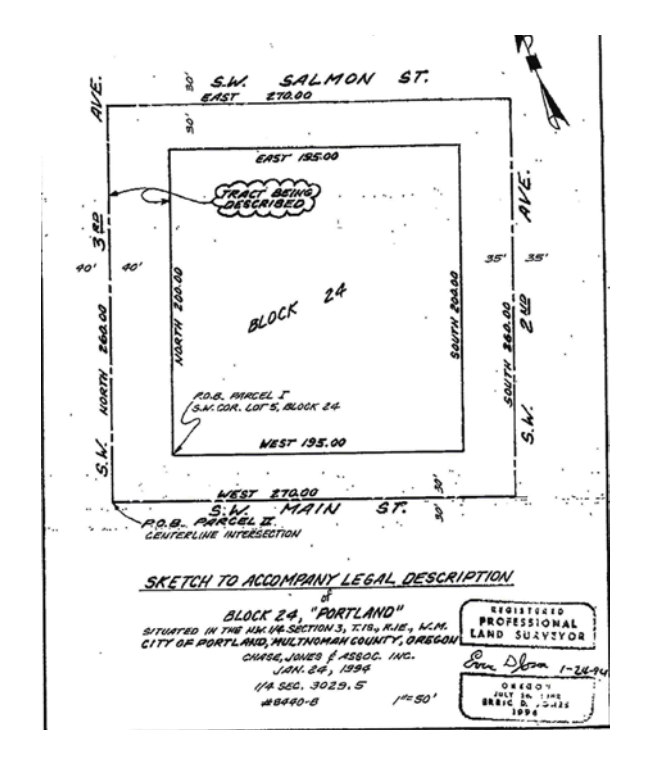

That’s because the three cases at the core of this debate all appear to involve assaults not at Portland Federal courthouse (marked with the green arrow), but assaults a block away, not on Federal property at all, probably close to the blue arrows marked below.

- David Bouchard, arrested overnight on July 23-24 at Main and 4th by a Federal Protection Services officer stationed in Colorado

- Joshua Webb, arrested overnight by a US Marshal on July 25-26 on Salman between 4th and 5th by a US Marshal

- Thomas Johnson, arrested overnight by a US Marshal on July 25-26 “in the park” (but because it appears to be the same instance as Webb, probably towards Main & 4th) by a US Marshal

All three of these arrest affidavits include a drawing of the city block that is Federal property, and then describe arrests that don’t take place on that Federal property.

The arrest affidavits offer no explanation for what led the Federal agents to leave the courthouse they were purportedly defending.

Specifically, on July 26, 2020, federal law enforcement officers attempted to disperse a crowd on SW Salmon Street between 4th and 5th streets in Portland, OR. The crowd was part of a protest that was declared an unlawful assembly by the Federal Protective Service and a riot by the Portland Police Bureau.

In other words, the story McFadden cites for his claim that there were thousands involved in the unrest involved direct reporting from the site the day between these arrests. His clerk researched and found a story about Portland from the week of these arrests, which featured elevated hostility and significantly expanded numbers, because (as even that story noted) Portland was reacting against Billy Barr’s decision to send in Federal agents.

Which brings us back to the NYT story that McFadden could have but did not rely on. It describes that on Friday morning — overnight on July 23 to 24, so covering events from the day when Bouchard was arrested — Federal officers were prowling the streets blocks away from the Hatfield Court House that they were purportedly protecting. And that created legal problems,

After flooding the streets around the federal courthouse in Portland with tear gas during Friday’s early morning hours, dozens of federal officers in camouflage and tactical gear stood in formation around the front of the building.

Then, as one protester blared a soundtrack of “The Imperial March,” the officers started advancing. Through the acrid haze, they continued to fire flash grenades and welt-inducing marble-size balls filled with caustic chemicals. They moved down Main Street and continued up the hill, where one of the agents announced over a loudspeaker: “This is an unlawful assembly.”

By the time the security forces halted their advance, the federal courthouse they had been sent to protect was out of sight — two blocks behind them.

The aggressive incursion of federal officers into Portland has been stretching the legal limits of federal law enforcement, as agents with batons and riot gear range deep into the streets of a city whose leadership has made it clear they are not welcome.

[snip]

Robert Tsai, a professor at the Washington College of Law at American University, said the nation’s founders explicitly left local policing within the jurisdiction of local authorities.

He questioned whether the federal agents had the right to extend their operations blocks away from the buildings they are protecting.

“If the federal troops are starting to wander the streets, they appear to be crossing the line into general policing, which is outside their powers,” Professor Tsai said.

Homeland Security officials say they are operating under a federal statute that permits federal agents to venture outside the boundaries of the courthouse to “conduct investigations” into crimes against federal property or officers.

But patrolling the streets and detaining or tear-gassing protesters go beyond that legal authority, said David Lapan, the former spokesman for the agency when it was led by John Kelly, Mr. Trump’s first secretary of homeland security.

“That’s not an investigation,” Mr. Lapan said. “That’s just a show of force.”

Indeed, these particular arrests happened just after the Portland City Council voted to cease cooperating with Federal authorities, as described by a DHS OIG Report reviewing the deployment (which McFadden’s clerk might have used to source a claim that the largest protest reached 10,000 participants, but which would have made the authorization problem clear), meaning that invoking the Portland Police Bureau covering the city generally (including where these arrests seem to have taken place) was particularly problematic.

However, on July 22, 2020, the Portland City Council voted to cease cooperation between the Portland Police Bureau and Federal law enforcement. The Portland City Council viewed Federal operations in Portland as an “unprecedented and unconstitutional abuse of power” by the Federal Government.11 According to the Portland City Council resolution, “the Portland Police Bureau shall not provide, request, or willingly receive operational support … from any agent or employee representing or constituting part of deployment under executive order from the president, be they from Department of Homeland Security, the U.S. Marshals Service, the Federal Protective Service, U.S. Customs and Border Protection or any other service.”1

The OIG Report states that officers had authority to be in Portland, but doesn’t address whether they had legal authority to do what the did in this case: leave the building they were protecting and go blocks away, looking for trouble.

An earlier DHS OIG Report described that officers sent into Portland had not been bureaucratically designated in the way they should have been and raised still-unanswered questions about whether DHS Acting Secretaries acted under legal authority when sending troops to Portland.

In other words, there seems to be a ready explanation — one that both DOJ and McFadden have reasons to suppress — for why these cases were diverted: for a number of reasons, the arrests were made under dubious legal authority. (At least one of the other ones Judd cites may have involved less-than-lethal force violation.)

But Trevor McFadden, who made very clear he wanted to consider this kind of selective prosecution claim and has whined for months that Jan6ers are being treated differently, doesn’t mention this ready explanation which (given the research his clerk did to find the AP article and others not included in the record before that) at least his clerk must know. Instead, McFadden goes on a multi-paragraph rant suggesting that DOJ — starting under, “a Republican-appointed U.S. Attorney (under the direction of a Republican-appointed Attorney General),” he notes elsewhere — started diverting these prosecutions in significant numbers.

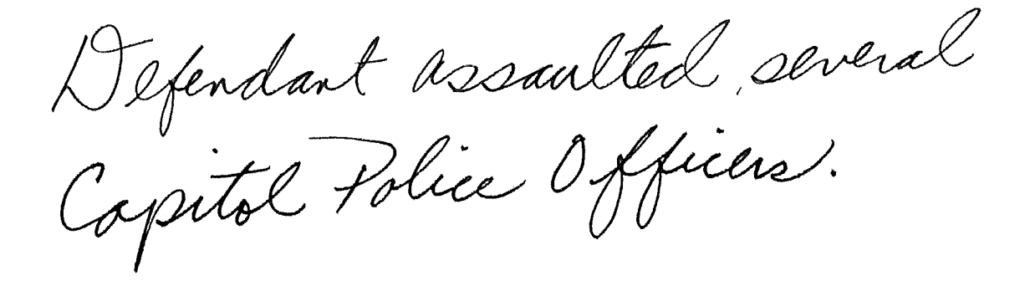

Judd’s claim is nontrivial. His chart suggests that Portland defendants generally received much lighter treatment than he has. For example, three Portland defendants allegedly struck officers in various ways. One placed an officer in a headlock. See United States v. Bouchard, No. 3:20-mj-00165 (D. Or.), ECF No. 1-1 at 4–5. Another punched and hit an officer in the face with a shield. See United States v. Webb, No. 3:20-mj-00169 (D. Or.), ECF No. 1 at 5. Yet another struck officers with a shield after he tried to pick up a smoke grenade. See United States v. Johnson, No. 3:20-mj-00170 (D. Or.), ECF No. 1 at 5. The Government charged these three defendants with felony assault on a federal officer, just as it charged Judd here. See Gov’t Opp’n at 17–18. That makes some sense—Judd was likewise allegedly present for a fracas with law enforcement at a federal building and used a firecracker (which if it had exploded, would have caused “bodily injury”) to “intimidate” law enforcement. 18 U.S.C. § 111(a). The Government could justifiably seek felony convictions for both Judd and the Portland defendants.

But, incredibly, the Government dismissed the charges against all three Portland defendants. See Bouchard, Motion to Dismiss Complaint, ECF No. 16; Webb, Motion to Dismiss Complaint, ECF No. 22; Johnson, Motion to Dismiss Complaint, ECF No. 9. Judd still faces nine charges, including multiple felonies, even though the Government never alleges that he, unlike the Portland defendants, struck or injured an officer. That he still faces greater charges than the Portland defendants despite that key difference is suspicious.5 That is the kind of “different treatment” that might warrant discovery. Armstrong, 517 U.S. at 470.

The Government responds that it treated Judd and the three Portland defendants equitably because it filed felony charges against all of them. See Gov’t Opp’n at 18. The Government seems to think that the initial charges are all that matter. Not so. By that logic, the Government could avoid discovery of a race-based selective prosecution claim if it indicted similarly situated black and white persons, dismissed the charges against the whites, and prosecuted the black defendants to conviction or plea. The “administration of a criminal law” is not limited to an initial charging decision. Armstrong, 517 U.S. at 464. Nor is it so easily circumvented.

More, the Government’s logic would allow it to charge similarly situated black defendants with felonies and white defendants with misdemeanors. But discriminatory effects include disparities in the “crimes charged.” Stone, 394 F. Supp. 3d at 31. The Government’s argument is thus absurd and untenable—that the Government originally indicted the Portland defendants does not erase the potential for discriminatory effect.6

Nor does the Court accept the Government’s attempt to distinguish these Portland cases on evidentiary grounds. According to the Government, video footage of Judd’s actions solidified the case against him, precluding a dismissal. See Gov’t Opp’n at 20. In contrast, Portland cases relied on officer recollections during nighttime attacks—none captured on video—by mostly masked assailants. See id. Fair enough. This could explain why fewer defendants overall were charged in Portland than here. But by indicting those cases, the Portland prosecutors presumably believed they had sufficient evidence to sustain convictions. See Justice Manual § 9-27.220 cmt. (“[N]o prosecution should be initiated against any person unless the attorney for the government believes that the admissible evidence is sufficient to obtain and sustain a guilty verdict by an unbiased trier of fact.”). If anything, that fact supports Judd’s argument. Evidentiary differences notwithstanding, the Government felt it had enough basis to charge both Judd and Portland defendants. Yet the Government dismissed the charges against only Portland defendants. The suggestion that Portland cases suffered from widespread, post-indictment, evidentiary challenges is thus a tough argument to swallow.

[snip]

Therein lies a troubling theme that emerges from a wholesale analysis of the Government’s decisions in Portland. The Government dismissed 27 cases brought against Portland defendants, including five felony cases. See generally Appendix to Def.’s Mot. Dismissal of one felony case is unusual. Dismissal of five is downright rare and potentially suspicious.7 Rarely has the Government shown so little interest in vigorously prosecuting those who attack federal officers. Considered in this light, when compared to Portland cases, the disposition of Judd’s case appears an outlier.

5 The D.C. U.S. Attorney’s Office also dismissed charges against the one D.C. defendant mentioned by Judd. She allegedly threw a firecracker at police during a Black Lives Matter protest in August 2020. See Affidavit in Support of Arrest Warrant, United States v. Rogers, No. 2020 CF3 006970 (D.C. Super. Ct. dismissed Sept. 30, 2020). The firecracker burned the pant leg of one officer. See id.

6 The Government wisely dropped this argument at the motion hearing. See Hr’g Tr. at 66.

7 By way of comparison, the Court knows of only one January 6 case that the Government has dismissed among the hundreds of defendants charged for their alleged actions on that day. See United States v. Kelly, No. 21-mj-00128 (D.D.C., dismissed on June 1, 2021). [my emphasis]

DC District’s Trumpiest judge here uses diversions most likely necessitated by the legal abuses and bureaucratic incompetence of the Trump Administration to claim that Jan6ers are being treated poorly. He focuses on arrests made, in very significant part, to fulfill Barr’s priority on such prosecutions in summer 2020, while ignoring the legally suspect circumstances created by Barr’s effort to gin up arrests. And he does so even as he refuses discovery that might confirm this most obvious of explanations.

The proper comparison to the cases McFadden focuses on would be to examine the arrests on January 5 and 6 in DC made by Federal officers away from the Capitol, such as Freedom Square. Yet in that case (particularly at the Washington Monument before the riot kicked off), the evidence suggests that Federal officers were far too lenient on Jan 6, even in the nation’s Capitol on Federal land. At least in the three cases as the center of this dispute, the disparate treatment in Portland appears to have come in the arrests outside of Federal property, not the prosecutorial diversions of those arrests later. Such a comparison would make it clear that Federal authorities treated Trump’s supporters far too lightly, not the opposite.

But McFadden has a goal here, one that — as he notes — he has been developing since at least July.

McFadden properly rules that Judd has not shown enough evidence of selective prosecution to get discovery into why these other prosecutions were diverted (in that, he may have been bound by an opinion issued days earlier by Trump appointee Carl Nichols in the Garret Miller case). Both Trump appointees note that Jan 6 is different from Portland for a number of reasons. In fact, McFadden cites Nichols in describing what he sees to be the difference.

Putting aside any claims that January 6 rioters sought to tear down our system of government (an allegation not made against Judd), their actions endangered hundreds of federal officials in the Capitol complex. Members of Congress cowered under chairs while staffers blockaded themselves in offices, fearing physical attacks from the rioters. See Lindsay Wise, Catherine Lucey, and Andrew Restuccia, “The Protestors Are in the Building.” Inside the Capitol Stormed by a Pro-Trump Mob, Wall St. J. (Jan. 6, 2021, 11:53 P.M.).8 The action in Portland, though destructive and ominous, caused no similar threat to civilians. Accord United States v. Miller, No. 21-cr-119 (CBN), slip order at 3 (D.D.C. Dec. 21, 2021) (“Nor did the Portland rioters, unlike those who assailed America’s Capitol in 2021, make it past the buildings’ outer defenses.”). Given the “narrow[ ]” interpretation of “similarly situated,” Stone, 394 F. Supp. 3d at 31, the Court cannot say that the Portland defendants “committed roughly the same crime under roughly the same circumstances” as Judd, Khanu, 664 F. Supp. 2d at 32.

But even after having laid out reasons (but ignoring the legal problems introduced by Federal big-footing in Portland) why you cannot compare Portland and Jan6, McFadden — who, again, invited this challenge — concludes that he will sentence Jan6ers leniently because he’s sure they’re being mistreated. McFadden cites himself saying he’ll account for such disparities at sentencing in the very same paragraph where he denies discovery to find out whether there’s an obvious explanation for such claimed disparities.

None of this suggests that the distinctions Judd highlights are irrelevant for all purposes. “Disparate charging decisions in similar circumstances may be relevant at sentencing.” United States v. Griffin, — F. Supp. 3d —, 2021 WL 2778557 at *7 (D.D.C. July 2, 2021); cf. 18 U.S.C. § 3553(a)(6) (“the need to avoid unwarranted sentence disparities among defendants with similar records who have been found guilty of similar conduct”). But on this record, those disparate outcomes fail to justify the discovery he seeks.

Then he cites Merrick Garland thinking he’s being clever.

Justice requires that “like cases be treated alike” and that “there not be one rule for Democrats and another for Republicans.” Merrick Garland, Remarks to DOJ Employees on His First Day, (Mar. 11, 2021).10 Otherwise, prosecutions risk becoming “so unequal and oppressive” as to deny the rights of all. Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356, 373 (1886). Especially during moments of politically charged unrest, the Justice Department must strive for even-handed justice. Judd raises troubling questions about the Department’s adherence to this imperative in Portland. But for the reasons stated above, he has not carried his burden to justify further discovery into the Government’s prosecutions.

Make no mistake what this is: It is an otherwise law-and-order touting Federal Judge announcing, in advance, that he’s going to sentence Jan6ers, people who share his political views, leniently because — he claims, even while refusing to order discovery to prove or disprove his hypothesis — Jan6ers are being badly treated.

And in fact he has already been doing that. When he sentenced Danielle Doyle to two months probation and a fine in October, rather than the three years of probation DOJ sought, he said as much.

Trevor McFadden used this challenge to lay out, for at least the third time, his plan to let Jan6ers off easy, presumably including Judd and his co-defendants, accused of attacking cops over the course of hours. And in the course of doing so, he has suppressed the evidence showing that the disparity, in fact, pertains to overpolicing, not lenient prosecutions, in Portland.

Update: In June DHS provided Ron Wyden with responses to some of his questions about the deployment. They claim they can operate 1-3 blocks from the Federal property which could include all of these arrests.

Practically speaking, DHS personnel deployed to support FPS in protecting federal property in Portland, like the Hatfield U.S. Courthouse, dispersed crowds approximately one to three blocks away from the federal property to secure the perimeter, contain/mitigate fires, treat officer injuries, and otherwise reconstitute facility security.

As set forth above, 40 U.S.C. § 1315 does grant cross-designated law enforcement personnel certain authorities at a distance from federal property. For instance, a cross-designated officer or agent may make arrests without a warrant for any offense against the United States committed in the presence of the officer or agent, or for any felony cognizable under the laws of the United States if the officer or agent has reasonable grounds to believe that the person to be arrested has committed or is committing a felony. Similarly, such an officer or agent may conduct.