The Disinformation Campaign Targeting Mueller and the Delayed Briefing to SSCI on Russian Election Interference

A lot of people are reporting and misreporting details from this Mueller filing revealing that it had been the target of disinformation efforts starting in October.

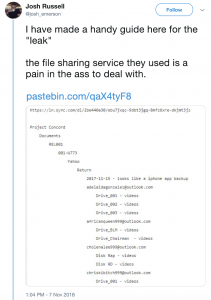

1000 non-sensitive files leaked along with the file structure Mueller provided it with

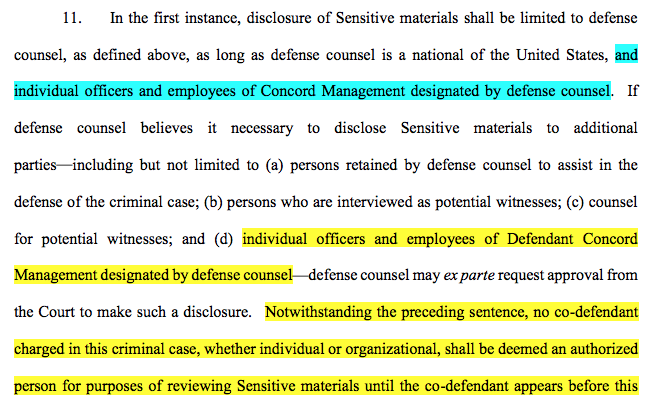

To substantiate an argument that Concord Management should not be able to share with Yevgeniy Prigozhin the sensitive discovery that the government has shared with their trollish lawyers, Mueller revealed that on October 22, someone posted 1000 files turned over in discovery along with a bunch of other crap, partially nested within the file structure of the files turned over in discovery.

On October 22, 2018, the newly created Twitter account @HackingRedstone published the following tweet: “We’ve got access to the Special Counsel Mueller’s probe database as we hacked Russian server with info from the Russian troll case Concord LLC v. Mueller. You can view all the files Mueller had about the IRA and Russian collusion. Enjoy the reading!”1 The tweet also included a link to a webpage located on an online file-sharing portal. This webpage contained file folders with names and folder structures that are unique to the names and structures of materials (including tracking numbers assigned by the Special Counsel’s Office) produced by the government in discovery.2 The FBI’s initial review of the over 300,000 files from the website has found that the unique “hashtag” values of over 1,000 files on the website matched the hashtag values of files produced in discovery.3 Furthermore, the FBI’s ongoing review has found no evidence that U.S. government servers, including servers used by the Special Counsel’s Office, fell victim to any computer intrusion involving the discovery files.

1 On that same date, a reporter contacted the Special Counsel’s Office to advise that the reporter had received a direct message on Twitter from an individual who stated that they had received discovery material by hacking into a Russian legal company that had obtained discovery material from Reed Smith. The individual further stated that he or she was able to view and download the files from the Russian legal company’s database through a remote server.

2 For example, the file-sharing website contains a folder labeled “001-W773.” Within that folder was a folder labeled “Yahoo.” Within that folder was a folder labeled “return.” Within the “return” folder were several folders with the names of email addresses. In discovery in this case, the government produced a zip file named “Yahoo 773.” Within that zip file were search warrant returns for Yahoo email accounts. The names of the email accounts contained in that zip file were identical to the names of the email address folders within the “return” subfolder on the webpage. The webpage contained numerous other examples of similarities between the structure of the discovery and the names and structures of the file folders on the webpage. The file names and structure of the material produced by the government in discovery are not a matter of public record. At the same time, some folders contained within the Redstone Hacking release have naming conventions that do not appear in the government’s discovery production but appear to have been applied in the course of uploading the government’s production. For example, the “001- W773” folder appears within a folder labeled “REL001,” which is not a folder found within the government’s production. The naming convention of folder “REL001” suggests that the contents of the folder came from a production managed on Relativity, a software platform for managing document review. Neither the Special Counsel’s Office nor the U.S. Attorney’s Office used Relativity to produce discovery in this case. [my emphasis]

It sounds like Mueller’s office found out about it when being contacted by the journalist who had been alerted to the content on Twitter.

But before Mueller asked Concord’s trollish lawyers about it, the defense attorneys — citing media contacts they themselves had received — contacted prosecutors to offer a bullshit excuse about where the files came from.

On October 23, 2018, the day after the tweet quoted above, defense counsel contacted the government to advise that defense counsel had received media inquiries from journalists claiming they had been offered “hacked discovery materials from our case.” Defense counsel advised that the vendor hired by the defense reported no unauthorized access to the non-sensitive discovery. Defense counsel concluded, “I think it is a scam peddling the stuff that was hacked and dumped many years ago by Shaltai Boltai,” referencing a purported hack of Concord’s computer systems that occurred in approximately 2014. That hypothesis is not consistent with the fact that actual discovery materials from this case existed on the site, and that many of the file names and file structures on the webpage reflected file names and file structures from the discovery production in this case.

Without any hint of accusation against the defense attorneys (though this motion is accompanied by an ex parte one, so who knows if they offered further explanation there), Mueller notes any sharing of this information for disinformation purposes would violate the protective order in the case.

As stated previously, these facts establish a use of the non-sensitive discovery in this case in a manner inconsistent with the terms of the protective order. The order states that discovery may be used by defense counsel “solely in connection with the defense of this criminal case, and for no other purpose, and in connection with no other proceeding, without further order of this Court,” Dkt. No. 42-1, ¶ 1, and that “authorized persons shall not copy or reproduce the materials except in order to provide copies of the materials for use in connection with this case by defense counsel and authorized persons,” id. ¶ 3. The use of the file names and file structure of the discovery to create a webpage intended to discredit the investigation in this case described above shows that the discovery was reproduced for a purpose other than the defense of the case.

Update: Thursday evening, Mueller submitted another version of this clarifying that the @HackingRedstone tweets alerting journalists to the document dump were DMs, and so not public (or visible to the defense). The first public tweet publicizing the dump came on October 30, so even closer to the election.

Shortly after the government filed, defense counsel drew the government’s attention to the following sentence, which appears on page nine of the filing: “On October 22, 2018, the newly created Twitter account @HackingRedstone published the following tweet: ‘We’ve got access to the Special Counsel Mueller’s probe database as we hacked Russian server with info from the Russian troll case Concord LLC v. Mueller. You can view all the files Mueller had about the IRA and Russian collusion. Enjoy the reading!’” Defense counsel pointed out that this sentence could be read to suggest that the Twitter account broadcast a publicly-available “tweet” on October 22. In fact, the Twitter account @HackingRedstone began sending multiple private direct messages to members of the media promoting a link to the online file-sharing webpage using Twitter on October 22. The content of those direct messages was consistent with, but more expansive than, the quoted tweet to the general public, which was issued on October 30. By separate filing, the government will move to file under seal the text of the direct messages. The online file sharing webpage was publicly accessible at least starting on October 22.

I’m not sure it makes the defense response any more or less suspect. But it does tie the disinformation even more closely with the election.

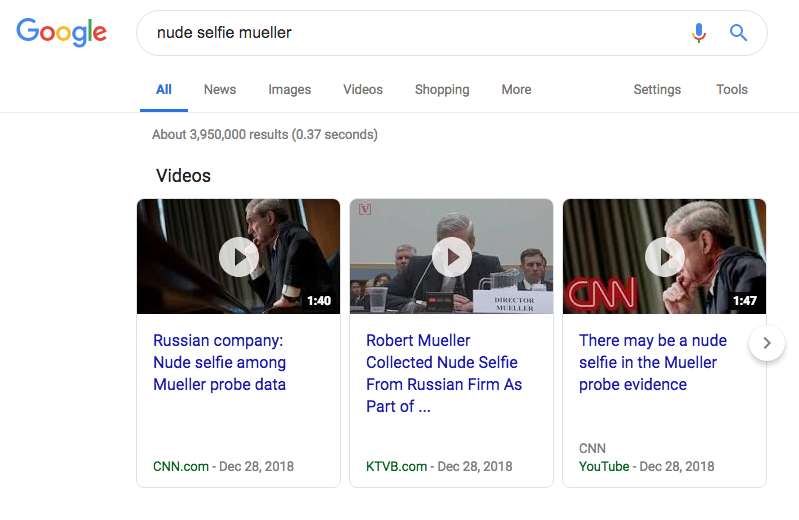

The Mueller disinformation was part of a month-long election season campaign

This thread, from one of the journalists who was offered the information, put it all in context back on November 7, the day after the election.

The thread shows how the release of the Mueller-related files was part of a month-long effort to seed a claim that the Internet Research Agency had succeeded in affecting the election.

Update: This story provides more background.

Other signs of the ongoing investigation into Yevgeniy Prigozhin’s trolls

Given how the Mueller disinformation functioned as part of that month-long, election oriented campaign, I’m more interested in this passage from the Mueller investigation than that the investigation had been targeted. Mueller argues that they shouldn’t have to share the sensitive discovery with Yevgeniy Prigozhin because the sensitive discovery mentions uncharged individuals who are still trying to fuck with our elections.

First, the sensitive discovery identifies uncharged individuals and entities that the government believes are continuing to engage in operations that interfere with lawful U.S. government functions like those activities charged in the indictment.

To be sure, we knew the investigation into Prigozhin’s trolls was ongoing. On October 19, just days before these files got dropped, DOJ unsealed an EDVA complaint, which had been filed under seal on September 28, against Prigozhin’s accountant, Alekseevna Khusyaynova. Along with showing Prigozhin’s trolls responding to the original Internet Research Agency indictment last February, it showed IRA’s ongoing troll efforts through at least June of last year.

Then, in December, Concord insinuated that Mueller prosecutor Rush Atkinson had obtained information via the firewall counsel and taken an investigative step on that information back on August 30.

On August 23, 2018, in connection with a request (“Concord’s Request”) made pursuant to the Protective Order entered by the Court, Dkt. No. 42-1, Concord provided confidential information to Firewall Counsel. The Court was made aware of the nature of this information in the sealed portion of Concord’s Motion for Leave to Respond to the Government’s Supplemental Briefing Relating to Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss the Indictment, filed on October 22, 2018. Dkt. No. 70-4 (Concord’s “Motion for Leave”). Seven days after Concord’s Request, on August 30, 2018, Assistant Special Counsel L. Rush Atkinson took investigative action on the exact same information Concord provided to Firewall Counsel. Undersigned counsel learned about this on October 4, 2018, based on discovery provided by the Special Counsel’s Office. Immediately upon identifying this remarkable coincidence, on October 5, 2018, undersigned counsel requested an explanation from the Special Counsel’s Office, copying Firewall Counsel on the e-mail.

[snip]

Having received no further explanation or information from the government, undersigned counsel raised this issue with the Court in a filing made on October 22, 2018 in connection with the then-pending Motion to Dismiss. In response to questions from the Court, Firewall Counsel denied having any communication with the Special Counsel’s Office.

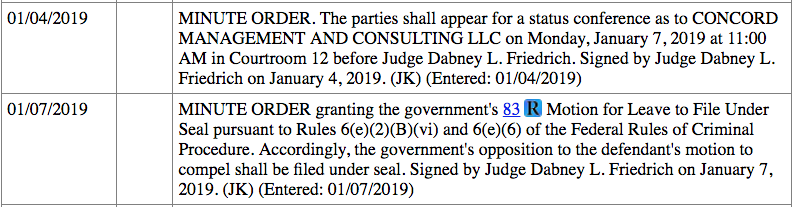

This was a bid to obtain live grand jury investigative information, one that failed earlier this month after Mueller explained under seal how his prosecutors had obtained this information and Dabney Friedrich denied the request.

What this filing, in conjunction with Josh Russell’s explanatory Twitter thread, reveals is that the Mueller disinformation effort was part of a disinformation campaign targeted at the election.

Dan Coats doesn’t want to share the report on Russian election tampering with SSCI

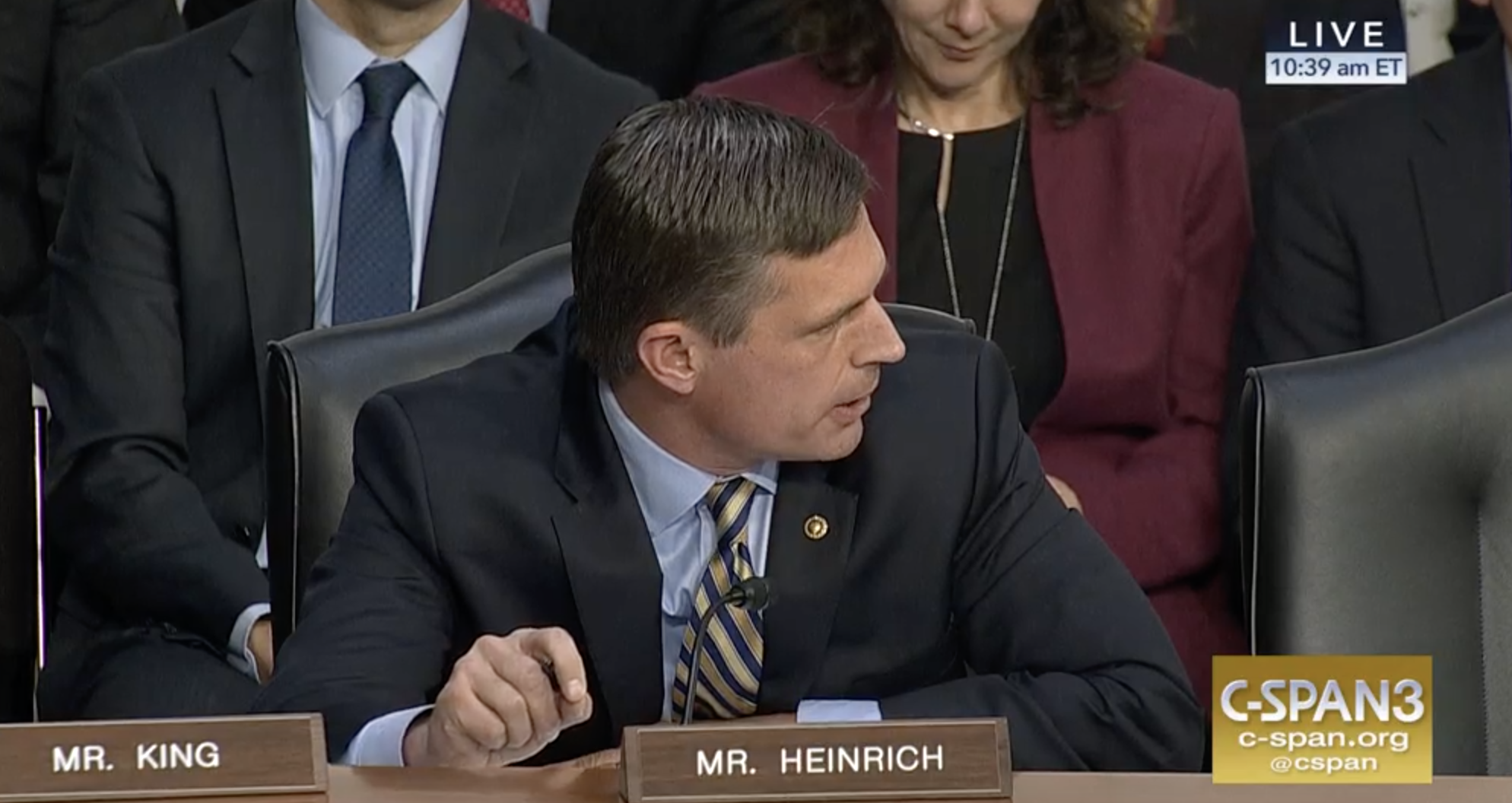

And I find that interesting because of a disturbing exchange in a very disturbing Global Threats hearing the other day. After getting both Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats and FBI Director Christopher Wray to offer excuses for White House decisions to given security risks like Jared Kushner security clearance, Martin Heinrich then asked Coats why ODNI had not shared the report on election tampering even with the Senate Intelligence Committee.

Heinrich: Director Coats, I want to come back to you for a moment. Your office issued a statement recently announcing that you had submitted the intelligence community’s report assessing the threats to the 2018 mid-term elections to the President and to appropriate Executive Agencies. Our committee has not seen this report. And despite committee requests following the election that the ODNI brief the committee on any identified threats, it took ODNI two months to get a simple oral briefing and no written assessment has yet been provided. Can you explain to me why we haven’t been kept more fully and currently informed about those Russian activities in the 2018–

Chairman Richard Burr interrupts to say that, in fact, he and Vice Chair Mark Warner have seen the report.

Burr: Before you respond, let me just acknowledge to the members that the Vice Chairman and I have both been briefed on the report and it’s my understanding that the report at some point will be available.

Coats then gives a lame excuse about the deadlines, 45 days, then 45 days.

Coats: The process that we’re going through are two 45 day periods, one for the IC to assess whether there was anything that resulted in a change of the vote or anything with machines, uh, what the influence efforts were and so forth. So we collected all of that, and the second 45 days — which we then provided to the Chairman and Vice Chairman. And the second 45 days is with DHS looking, and DOJ, looking at whether there’s information enough there to take — to determine what kind of response they might take. We’re waiting for that final information to come in.

After Coats dodges his question about sharing the report with the Committee, Heinrich then turns to Burr to figure out when they’re going to get the information. Burr at least hints that the Executive might try to withhold this report, but it hasn’t gotten to that yet.

Heinrich: So the rest of us can look forward — so the rest of us can then look forward to reading the report?

Coats: I think we will be informing the Chairman and the Vice Chairman of that, of their decisions.

Heinrich: That’s not what I asked. Will the rest of the Committee have access to that report, Mr. Chairman?

[pause]

Heinrich: Chairman Burr?

Burr; Well, let me say to members we’re sort of in unchartered ground. But I make the same commitment I always do, that anything that the Vice Chairman and myself are exposed to, we’ll make every request to open the aperture so that all members will be able to read I think it’s vitally important, especially on this one, we’re not to a point where we’ve been denied or we’re not to a point that negotiations need to start. So it’s my hope that, once the final 45-day window is up that is a report that will be made available, probably to members only.

Coming as it did in a hearing where it became clear that Trump’s spooks are helpless in keeping Trump from pursuing policies that damage the country, this exchange got very little attention. But it should!

The Executive Branch by law has to report certain things to the Intelligence Committees. This report was mandated by Executive Order under threat of legislation mandating it.

And while Coats’ comment about DOJ, “looking at whether there’s information enough there to take — to determine what kind of response they might take,” suggests part of the sensitivity about this report stems from a delay to provide DOJ time to decide whether they’ll take prosecutorial action against what they saw in the election, the suggestion that only members of the committee (not staffers and not other members of Congress) will ever get the final report, as well as the suggestion that Coats might even fight that, put this report on a level of sensitivity that matches covert actions, the most sensitive information that get shared with Congress.

Maybe the Russians did have an effect on the election?

In any case, going back to the Mueller disinformation effort, that feels like very familiar dick-wagging, an effort to make key entities in the US feel vulnerable to Russian compromise. Mueller sounds pretty sure it was not a successful compromise (that is, the data came from Concord’s lawyers, not Mueller).

But if the disinformation was part an effort to boast that Putin’s allies had successfully tampered with the vote — particularly if Russia really succeeded in doing so — it might explain why this report is being treated with the sensitivity of the torture or illegal spying program.

Update: I’ve corrected this to note that in the end the Intelligence Authorization did not mandate this report, as was originally intended; Trump staved that requirement off with an Executive Order. Still, that still makes this look like an attempt to avoid admitting to Congress that your buddy Putin continues to tamper in US elections.

As I disclosed last July, I provided information to the FBI on issues related to the Mueller investigation, so I’m going to include disclosure statements on Mueller investigation posts from here on out. I will include the disclosure whether or not the stuff I shared with the FBI pertains to the subject of the post.