Pandora’s Presidential Archives, Couy Griffin Edition

The attorney for New Mexico politician and Cowboys for Trump founder, Couy Griffin, is a guy named Nick Smith.

He is laudably aggressive. And in a case in which Griffin was charged just with trespassing (18 USC 1752), Smith has fought the prosecution every step of the way, even though if Griffin were to get jail time, he already served time after his arrest and so likely would only get time served.

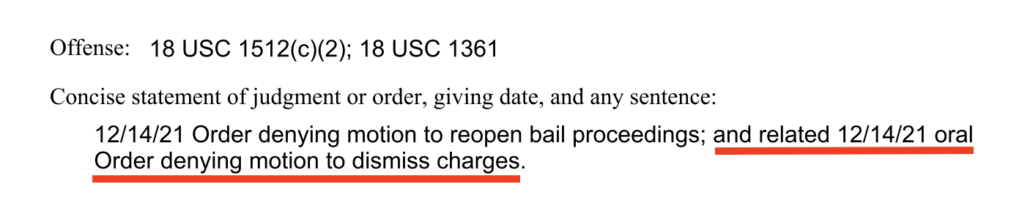

In July, DC’s Trumpiest judge, Trevor McFadden, soundly denied Griffin’s first attempt to get the 1752 charges thrown out, arguing that Smith’s legalistic interpretation of the required role of Secret Service didn’t accord with the statutory history.

While Griffin clings to this statutory history, it ends up being more cement shoes than life preserver. By 2006 Congress rewrote the statute, in the process eliminating reference to the Treasury Department and to any “regulations” from any executive branch agency. 5 18 U.S.C. § 1752 (2006). More, the new statute criminalized merely entering or remaining in a restricted area; the old statute required further action, such as impeding government business, obstructing ingress or egress, or physical violence. Compare 18 U.S.C. § 1752(a)(1) (2006) with 18 U.S.C. § 1752(a) (1970). But Congress did not stop there. In 2012 it reconfigured the statute, adding the term “restricted buildings or grounds” and then defining it under subsection (c), as it appears today. 18 U.S.C. § 1752(a) (2012). Congress did not take that opportunity to clarify who can or must do the restricting, leaving it open-ended. But Congress did lower the mens rea requirement, striking the requirement that a defendant act “willfully.”

So what should the Court gather from this foray into § 1752’s statutory history? “Not much” would be a fair answer. Perhaps better would be to recognize the direction of Congress’s legislative march, where at every turn it has broadened the scope the statute and the potential for liability. Even if Griffin were correct that earlier versions required Secret Service authorizations of restrictions, the Court cannot reconstitute provisions that Congress has jettisoned. And the Court cannot agree with Griffin that woven through these increasingly broad versions of the statute was a latent limitation that only the Secret Service could effectively post, cordon off, or restrict an area.

But in the wake of the description in Jon Karl’s book of where Mike Pence hid from the rioters, Smith tried again, arguing that the space where Mike Pence was evacuated was a garage for another building of the Capitol. Smith argued that meant Pence was not present (and therefore the necessary trigger for 1752 was absent). Smith wants the photos that the Secret Service assuredly wants to keep secret (because it reveals the location of a VIP security location), though the language he cites appears to prove him wrong.

The Senate garage, and underground tunnels leading to it, do not fall under the statutory definitions of the Capitol Building and Capitol Grounds. As shown above, all the features making up the “United States Capitol Grounds” are, appropriately enough, above ground. § 5102(a). As to whether the tunnels and Senate underground garage are part of the “Capitol Building” itself, Title 40 answers in the negative. “Capitol Buildings” are defined as follows:

[T]he term “Capitol Buildings” means the United States Capitol, the Senate and House Office Buildings and garages, the Capitol Power Plant, all buildings on the real property described under section 5102(c) (including the Administrative Building of the United States Botanic Garden) all buildings on the real property described under section 5102(d), all subways and enclosed passages connecting two or more of those structures, and the real property underlying and enclosed by any of those structures. 40 U.S.C. § 5101 (emboldening added).

As seen above, the definition of “Capitol Buildings,” plural, distinguishes between the tunnels and underground garages, on the one hand, and the “United States Capitol” building itself, on the other. The “subways,” underground “enclosed passages,” and “garages” are not part of the “United States Capitol” building (the “restricted” building) because they are set off from one another by commas in a list.

Photographic evidence showing that the Secret Service protectee was not present in the § 1752 “building” or “grounds” at the same time as Griffin is Brady material. It should be produced by the government. If it is not, the Court should dismiss the charges pursuant to Local Criminal Rule 5.1(g)(4), as Griffin would then be denied access to evidence going to the heart of his case.

The government response didn’t address the question posed by Smith’s filing, “what is a garage.”

Instead, in a footnote, DOJ says that the photos would not be exculpatory in any case.

The government rejects the Defendant’s contention that the photographs that are the subject of the Defendant’s motion have some exculpatory value. 18 U.S.C. 1752(a)(1) and (2) criminalizes a person entering a restricted area “of a building or grounds where the President or other person protected by the Secret Service is or will be temporarily visiting.” 18 U.S.C. 1752(c)(1)(B). 18 U.S.C. 1752 does not require the Secret Service protectee to be present on the grounds or in the building where the restricted area has been established at the time of an illegal entry into the restricted area. Therefore, the Vice President’s presence in an underground parking garage or tunnel does not exculpate the Defendant with respect to the charged conduct.

But the bulk of the response says that the photos are not Brady because the government doesn’t have possession of the photos.

Brady material is material in the government’s possession that has some exculpatory or impeachment value. United States v. Nelson, 979 F.Supp.2d 123 (D.C. Cir. 2013). The photographs requested by the Defendant from the official White House photographer are not in the government’s possession, therefore, they are not considered Brady and the Defendant cannot move to compel their production.1 United States v. Flynn, 411 F.Supp.3d 15 (D.C. Cir. 2019) (“Brady does not extend to information that is not within government’s possession…”). Similarly, the Defendant’s request for these photographs under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 16(a)(1)(E) should be denied, as Rule 16 only requires the government to disclose photographs within its possession. Fed. R. Crim. P. 16(a)(1)(E).

It’s not clear exactly what DOJ means by this. But according to President Obama’s White House photographer, Pete Souza, the photos should be in the Archives.

The Presidential Records Act requires that all records including “photographs” be turned over to the National Archives at the end of each administration. This includes Vice Presidential records. Congress should determine why the Archives doesn’t have them.

My guess is that’s precisely where they are, but they don’t count as being in the Executive Branch’s possession because of the way the Presidential Records Act deals with Presidential files. As the National Archives explained in Trump’s lawsuit, Trump’s records count as Presidential records for a period.

In 1978, guided by the Supreme Court’s reasoning in Nixon v. GSA, 1 Congress enacted the PRA, which changed the legal ownership of the official records of the President from private to public, and established a new statutory structure under which Presidents, and subsequently NARA, must manage the records of their Administrations. Under the PRA, records reflecting “the activities, deliberations, decisions, and policies” of the Presidency are “maintained as Presidential records.” 44 U.S.C. § 2203(a). When a President leaves office, the Archivist “assume[s] responsibility for the custody, control, and preservation of, and access to” the Presidential records of the departing administration. Id. § 2203(g)(1). The Archivist generally must make records covered by the PRA available to the public under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) starting five years after the President leaves office. Id. § 2204(b)(2), (c)(1); see also 36 C.F.R. § 1270.38. However, the outgoing President may specify that access to records in six defined categories be restricted for up to twelve years after leaving office. 44 U.S.C. § 2204(a); see also 36 C.F.R. § 1270.40(a).

We know Trump is asserting that right with respect to January 6, because as we speak, Trump is asking the Supreme Court to uphold his claim that no one else can access his records without his permission.

Of course, Judge McFadden could order DOJ that it needs to search the Archives for matters pertinent to the investigation — this investigation, and January 6 generally.

I’m sure DOJ would love that! In the case of Griffin, that would give DOJ access to the meeting that Griffin had directly with Trump, and any other contacts that are stored as Presidential Records.

But in the case of Nick Smith’s other clients — most notably Ethan Nordean — it would make records of Trump’s contacts with Proud Boys available, including records on what Enrique Tarrio was doing at the White House in December 2020.

So by all means, let’s have the Trumpiest Judge order DOJ to search through Trump’s records to find discovery pertinent to the January 6 attack, including the pictures of Mike Pence hiding from Trump’s mobsters. But along with that, let’s have the records of Trump’s contacts with them in advance of the insurrection.

Update: Griffin’s lawyers have responded. After having submitted proof that where Pence was was in the Capitol, they now play word games to suggest that “will be” is the same as “is” (and yes, the government has submitted evidence Griffin knew this).

The government is mistaken in several respects. “[R]estricted buildings or grounds” means “any posted, cordoned off, or otherwise restricted area . . . of a building or grounds where the President or other person protected by the Secret Service is or will be temporarily visiting.” § 1752(c)(1)(B). Thus, Griffin did not “knowingly enter[] or remain[] in any restricted building or grounds,” § 1752(a)(1), if the vice president was not also present and “temporarily visiting.”

Still, Griffin claims the government has not addressed their Rule 16 claim, and so DOJ must go to NARA and get the photos for him.

The government does not dispute that an official White House photographer took the photographs of the vice president as he passed time outside the “restricted area” on January 6. ECF No. 70. Accordingly, under the Presidential Records Act, the images are records documenting the “activities” of the vice president concerning his “constitutional, statutory, or other official or ceremonial duties. . .” and are thus Presidential records. 44 U.S.C. § 2203(a). When a president leaves office, the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) assumes “custody [and] control” over Presidential records. § 2203(g)(1). Records of the vice president are transferred to NARA in the same manner. § 2207. NARA is an agency of the Executive branch. § 2102.

Therefore, the government has an obligation to obtain the photographs from NARA and produce them to Griffin, so long as they are merely “material to preparing the defense,” much less Brady material.1 Fed. R. Crim. P. 16(a)(1)(E)(i). It is uncontroversial that satisfying this standard is “not a heavy burden.” United States v. Lloyd, 992 F.2d 348, 351 (D.C. Cir. 1993). Griffin must merely make a showing that the material will “play an important role in uncovering admissible evidence, aiding witness preparation, corroborating testimony, or assisting impeachment or rebuttal.” Id. Of course, if the requested material is “inconsistent with or tends to negate the defendant’s guilt as to any element . . . of the offense(s) with which the defendant is charged” it is also Brady material. LCrR 5.1(b)(1). “[B]urdensomeness and logistical difficulty . . . cannot drive the decision whether items are ‘material’ to preparation of the defense. Nor can concerns about confidentiality and privacy rights of others trump the right of one charged with a crime to present a fair defense.” United States v. O’Keefe, 2007 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 31053, at *4 (D.D.C. Apr. 27, 2007).

As I said, I look forward to, on Trevor McFadden’s order, DOJ going to NARA and getting all the records pertinent to Griffin among Trump’s records. The government can supersede Griffin while he continues to dawdle, and Trump’s own records of Griffin’s relationship might change DOJ’s understanding of the case.

The same is all the more true for the militia defendants that the Smiths represent.

They’re doing this just as SCOTUS’ inaction is creating the opportunity for NARA to provide the first 4 pages of which Trump has claimed privilege over to the Select Committee.