Socially Normative Agency And Rights

Michael Tomasello’s book, The Evolution Of Agency, presents a model of the evolution of agency, not cognition, not emotion, not the physique or eating habits of Homo sapiens. It’s packed with references to academic papers and books, but in the end, it has to be understood as a series of hypotheses generated by Tomasello from his own research, and his extensive study in this area.

Any extension of this model, for example, trying to use it to understand our own culture, is mere speculation until it is tested. That’s true no matter how obvious the extrapolation might seem. With that caveat I’ve been thinking about the implications of this model.

Self-awareness

Here’s an example of Tomasello’s understanding of human agency as an individual attribute:

Most of the unique psychological capacities of the human species result, in one way or another, from adaptations geared for participation in either a joint or a collective agency. Through participation in such agencies, humans evolved special skills for (i) mentally coordinating with others in the context of shared activities, leading to perspectival and recursive, and ultimately objective, cognitive representations; and (ii) relating to others cooperatively within those same activities, leading to normative values of the objectively right and wrong ways to do things. Individuals who self-regulate their thoughts and actions using “objective” normative standards are thereby normative agents, very likely characterized by a new form of socially perspectivized consciousness, what we might call self-consciousness. P. 117.

In this picture, we evolved to cooperate. One crucial focus of cooperation is forming a useful picture of reality, one that we can use safely to plan our actions.

Side effects of socially normative agency

Tomasello’s evolutionary history leaves off around perhaps 50,000 or so years ago, when humans lived in small bands, loosely connected in cultural groups. That mode of life continued until about 6,000 years ago, when humans began to live in cities.

In The Dawn Of Everything, David Graeber and David Wengrow look at this history of our ancestors from a different perspective. I really like two of their ideas.

- “… As soon as we became humans, we started doing human things.” P. 83.

- “There is an obvious objection to evolutionary models which assume that our strongest social ties are based on close biological kinship: many humans just don’t like their families very much.” P. 279.

Following these points out, most of the rules of cultural normativity must have seemed critical for survival ti early modern humans, even if the connection didn’t seem obvious to a child or an adolescent, or an outsider. But as the millennia pass, some of the norms might have seemed wrong or unnecessary, and oppressive. The young might have been unwilling to put up with the demands of their elders and especially their parents but lacked the ability to change things.

This is the Wikipedia summary of Sigmund Freud’s book Civilization and Its Discontents:

… Freud theorized the fundamental tensions between civilization and the individual; his theory is grounded in the notion that humans have certain characteristic instincts that are immutable. The primary tension originates from an individual attempting to find instinctive freedom, and civilization’s contrary demand for conformity and repression of instincts. Freud states that when any situation that is desired by the pleasure principle is prolonged, it creates a feeling of mild resentment as it clashes with the reality principle.

Primitive instincts—for example, the desire to kill and the insatiable craving for sexual gratification—are harmful to the collective wellbeing of a human community. Laws that prohibit violence, murder, rape and adultery were developed over the course of history as a result of recognition of their harm, implementing severe punishments if their rules are broken. This process, argued Freud, is an inherent quality of civilization that gives rise to perpetual feelings of discontent among individuals, justifying neither the individual nor civilization. Fn omitted.//

We don’t talk about instincts much anymor, and the question of mutability of instincts is open, but I think Freud has a sharp insight here. We all have moments when we feel out of control with rage or grief or hatred or …. We might have fantasies about guillotines for particularly loathsome elites or having sex with a co-worker. But mostly we just get over it and move on.

Tomasello would attribute this to our socially normative agency, and that makes a lot of sense.

Here’s an example used by Tomasello. A hunting party from a band kills an antelope. There are three competing interests. First, the successful hunter needs to eat, and wants to get as much as possible. Second, the hunter has a normative duty to the rest of the hunting party to share. Third, the hunter and the rest of the hunting party have a normative duty to carry the kill back to the rest of the band for disposition as the band decides.

Bands and cultures survive because the hunters bring the food home. But each time, the individuals experience a conflict in that they are unable to satisfy their selfish desires.There must have been cheating. Sometimes an individual or a group must have defected. Defection too has survival value, at times more so than the survival value associated with membership in the band. But that may well have produced an equally unpleasant sensation for many, guilt.

We aren’t so evolved we’ve lost our urge to satisfy our personal desires, or our willingness to satisfy our personal urges if we can or provide for our families even at the expense of the community. Thus the incidence of violence and sexual adventures, and the negative feelings and damage that go with those events.

Rights as limits on the demands of one’s community

In the past several thousand years we humans have lived in large communities, from a few tens of thousands to over a billion. We’ve endured all kinds of governments, from more or less egalitarian consensus-driven groups to totalitarian dystopias. Freud’s insight, and those of Graeber and Wengrow, apply to all of them. There will always be a conflict in the minds of many of us between the demands of society and our personal desires.

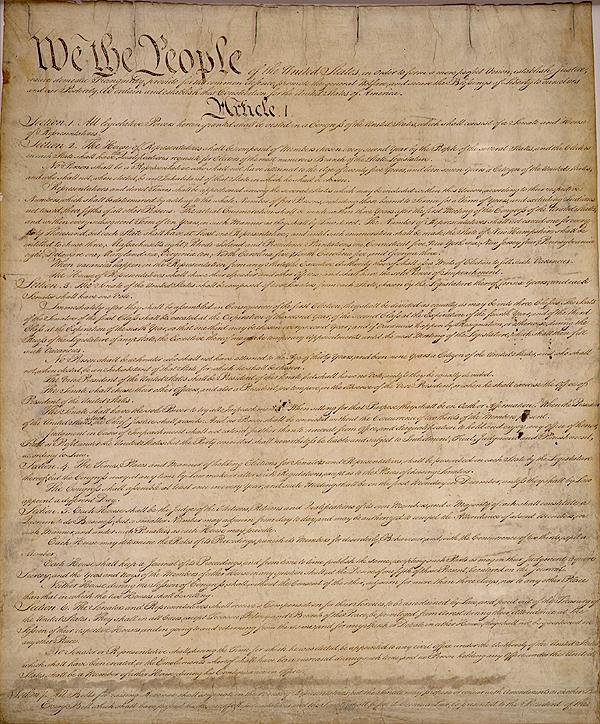

The Founders said that the point of government was to protect the rights given to people by the Creator, but they were just as worried about the dangers of government. They said the just powers of the government derived from the consent of the governed, but they were just as worried about the dangers of oppression by the majority. The solution they adopted was government of limited powers and the Bill of Rights.

The hope was to balance the desires of the individual members of society against the need to maintain a community in which everyone can flourish.

The idea, in other words, is that rights set the boundaries of the demands society can make on us. those limits

Discussion

1. I like Tomasello’s suggestion that one feature of shared agennce is the construction of a onsensus picture of the reality confronting the group, so that sensible shared decisions can be made. This was doable 10,000 years ago, but in our radically different world it’s hard. We’ve replace full consensus with majority rule

2. We should think about their impact of rights on our society as a whole, more than the feelings of the individuals claiming rights. Let’s take guns as an example. What kind of society do gun rights advocate think we should have? Should people with the history of Zackey Rahimi be allowed to have guns? Should this decision be made by 5 unaccountable unconstrained members of SCOTUS? Or should the majority decide based on their understanding of the nature of a good society?